The Bristol M.1 Monoplane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FUN for 13 1 Bristol Tram

8 9 ENTRY / EXIT 15 FUN FOR 13 1 Bristol Tram VIEWPOINT 2 Bristol Boxkite (flying model) THE KIDS Take a #ConcordeSelfie 3 Bristol F.2B Fighter 17 14 10 Keep your little engineers and 4 Bristol Scout 16 12 future pilots entertained from BAe M 5 Bristol lorry take-off to landing... ? POP-UP SHOP 7 Take home a Treat 6 Jupiter VI engine 11 ? 7 Hercules engine A Family 24 N Pick up your free Fact 8 Beaufighter forward fuselage 19 ? ? Finder leaflet and help 20 CONCORDE SHOW9 Proteus engine 18 Alfie Fox on his fantastic A UNIQUE EXPERIENCE10 Bristol Type 171 Sycamore helicopter fact-finding trail. The story of Concorde ON BOARD Inspiring School Visits Cockpit Seats: ? 3 Signatures on Design an aeroplane! Launch a rocket! Journey brought to life the door: through time! A school visit to Aerospace Bristol 11 Bristol Type 173 twin rotor helicopter Number of toilets: ? is a chance to develop STEM skills and reach 22 new heights. To fi nd out more please visit: 21 FILM A l fi e F o x TOILETS 6 Crew: aerospacebristol.org/schools 12 Bristol 403 car (cutaway) Passengers: ? Can you collect all of 23 4 Top Speed: ? Top Altitude: Fact Finder Leafl et kindly sponsored by SKF Bearings the aeroplane stamps? 13 Bristol Britannia forward fuselage EXHIBITION Can you help Alfie fi nd the aircraft London to New York: ? information cards around the exhibition London to Washington: Grab a clocking-in ? and fi ll in the missing facts? 2 London to Barbados: ? 14 Bristol Bloodhound Missile Paris to New York: card and search for the 23 www.skf.co.uk Bristol Aero Collection Trust: charity no. -

VA Vol 6 No 6 June 1978

actiVities. Due to the limited parking space available a pair of antique goggles for sponsoring five new in the Display Aircraft Parking Area, we do not plan members and a leather flying helmet for sponsor to park the aircraft by type. However, we do have ing ten new members. Don't forget, the big prize is the aircraft type signs available, so if any type clubs a five year free membership to the member who spon want to have their own row(s), we shall be happy to sors the most new members by the end of 1978. Let's supply the signs, but it will be necessary for them to see how many helmets and goggles you can win. There make arrangements directly with the Antique/Classic is no limit. Division Parking Chairman, Arthur R. Morgan, 3744 North 51st Boulevard, Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53216, before July fifteenth and to police their own rows with JOINT DIVISIONS MEETING their own members starting on Wednesday, July 26, AT EAA HEADQUARTERS and continuing through the entire convention period. While we are talking about the Display Aircraft The Officers and Directors of the Antique Classic Parking Area we would like to point out that the EAA Division, the Warbirds and the International Aero Convention is somewhat different from the average batic Club met on April 29th for the first annual Joint fly-in which we usually attend . EDUCATION is the Divisions Meeting. Chaired by Paul and Tom Pober basic theme of the EAA Convention, and your Antique/ ezny, the agenda focused on the state of the divisions Classic Division tries to encou rage this theme in both and more effective methods of working together in its forums and its Display Aircraft Parking Areas. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

The M.A.C. Flyer

April 2019 Vol No. 54 THE M.A.C. FLYER OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE MARLBOROUGH AERO CLUB INC. P.O. Box 73, Blenheim, 7240 Tel: (03) 578 5073 Email: [email protected] www.marlboroughaeroclub.co.nz M.A.C. Marlborough Aero Club PATRON PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT John Sinclair Alistair Matthews Scott Madsen Ph: 03 578 7110 Ph: 027 428 7863 Ph: 027 453 9348 HON. TREASURER SECRETARY Corrie Pickering Raylene Wadsworth Ph: 027 570 4881 Ph: 03 578 5073 COMMITTEE Mike Rutherford, Grant Jolley, Marty Nicoll, Victoria Lewis, John Hutchison, Jonathon Large CHIEF FLYING INSTRUCTOR CLUB CAPTAIN Sharn Davies Ben Morris Ph: 03 578 5073 Ph: 027 940 3235 Check out our new website – www.jemaviation.co.nz Annual Inspections, ARA / BRA’s, repairs, modifications and rebuilds – we can handle it all! Ph. (03) 578 3063 Mob. 021 504 048 Email [email protected] Hangar 22b, Aviation Heritage Centre Airpark, Omaka Aerodrome, Blenheim, NZ 2 PRESIDENT’S REPORT Fresh from the monthly committee meeting last week which was fairly straight forward. We have seen the provisional end of year results which are now being audited and put in to the usual annual report. While an overall loss is indicated there have been a number of high expenditure items this year but that sets us up for the next 10+ years. I will make further comment when the full report is out. The club is still in a healthy position and keeps it’s good name out there as was evidenced by the complimentary comments from recent air show participants. -

Vintage and Classic Spring-2019 Issue 65

Vintage & Classic The Journal of the Vintage Aircraft Club V A C www.vintageaircraftclub.org.uk | Issue 65 | Spring 2019 The VAC Committee VAC Honorary President - D F Ogilvy OBE FRAeS VAC Committee Chair Anne Hughes 01280 847014 email [email protected] Vice Chair and Secretary Steve Slater 01494 786382 email [email protected] Treasurer Peter Wright 07966 451763 email [email protected] Membership Secretary Stephanie Giles 01789 470061 email [email protected] Events Anne Hughes as above Magazine Editor Tim Badham email [email protected] Safety Officer Trevor Jarvis email [email protected] Trophy Steward Rob Stobo 01993 891226 email [email protected] Webmaster Mark Fotherby In this issue David Bremner tells us more about the email [email protected] incredible Bristol Scout. Meanwhile, we caught him hitching a lift, while trying not to drop a bombshell! Merchandise Cathy Silk email [email protected] New member ● Paul Gower from Billericay General Data Protection Regulation In accordance with the new EU directive concerning Contents Data Protection, the VAC committee has put together Notes from the Chair 4 the VAC policy and set up a sub-committee to ensure all updates are made at regular intervals. VAC Events 4 Rare breeds ‘rescuer’ 6 Aim of the VAC Welcome to Breighton Aerodrome: Yorkshire’s only home of vintage and classic aeroplanes 12 The aim of the Vintage Aircraft Club is to provide a Pure nostalgia! 14 focal body for owners, pilots and enthusiasts of vintage and classic aircraft by arranging fly-ins and Bristol Scout 1264 (Part 2) 18 other events for the benefit of its members. -

Model Builder February 1977 Full Size Plans Available - See Page 104 25 Photos by Dick Benjamin

It's habit with these MRC-WEBRA SCHNEURLE SPEED MTV (1014) COMPETITION UPDATE WINNERS OF 1975 LAS VEGAS, NEVADA NOVEMBER, 1976 For the second successive year the controllable power and high performance CIRCUS CIRCUS TOURNAMENT OF CHAMPIONS characteristics of the MRC-Webra Speed .61 TV and the talents of Rhett Miller III Webra Speed .61 (1024 RC) have joined forces to win the Nationals Pattern Championships. Places 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th. No mean feat, two consecutive National Championship wins is proof positive that these two are the best in and on the field. This year as last, when the best fliers and engines are gathered together, it’s the Schneurle Speed .61 from MRC-Webra that proves its superiority with flying colors Solid idle, minimum vibration and consistently reliable performance all add up to a winning habit. Those like Rhett Miller, the National Champ, and Wolfgang Matt, the International Champ, who can have their choice of any engine in the world, consistently choose MRC-Webra . and just as consistently they win the big ones. See your hobby dealer and ask him to help you break into a winning habit, with the MRC-Webra Schneurle Speed .61TV (1024). MODEL RECTIFIER CORP. / 2500 WOODBRIDGE AVE. / EDISON. NEW JERSEY 08817 SELECTED ITEMS FROM THE SIG CATALOG SIG HEAT PROOF FUEL LINE CONTEST RUBBER STILL THE FINEST AVAILABLE. There are competing brands of silicone tubing but we think none are better than 1/8" X 25' ...... ..$ 49 this time-proven favorite. IT WILL NOT HARDEN IN FUEL. 1/8" X 50' ...... 89 We have models using Sig Heat-Proof as the pick-up tubing 3/16" X 25' ... -

The Aircraft Flown by 24 Squadron

The Aircraft Flown by 24 Squadron 24 Squadron RAF is currently the Operational Training Squadron for the Lockheed C130J Hercules, based at RAF Brize Norton in Oxfordshire. Apart from a short period as a cadre in 1919, they have been continuously operating for the RFC & RAF since 1915. They started off as a Scout (Fighter) Squadron, developed into a ground attack unit, became a communications specialist with a subsidiary training role, and in 1940 became a transport squadron. I have discovered records of 100 different types being allocated or used by the Squadron, some were trial aircraft used for a few days and others served for several years, and in the case of the Lockheed Hercules decades! In addition many different marks of the same type were operated, these include; 5 Marks of the Avro 504 1 civil and 4 Military marks of the Douglas DC3/ Dakota All 7 marks of the Lockheed Hudson used by the RAF 4 marks of the Lockheed Hercules 5 marks of the Bristol F2B fighter 3 Marks of the Vickers Wellington XXIV Squadron has operated aircraft designed by 39 separate concerns, built in Britain, Belgium, France, Germany, Holland, and the USA. The largest numbers from one maker/ designer are the Airco and De Havilland DH series totalling 22 types or marks, followed by 12 types or marks from Lockheed, and 11 from Avro. The total number of aircraft operated if split down into different marks comes to 137no from the Airspeed “Envoy” to the Wicko “Warferry” Earliest Days 24 Squadron was formed at Hounslow as an offshoot of 17 Squadron on the 1st September 1915 initially under the command of Capt A G Moore. -

Aircraft Crash Sites at Sea: a Scoping Study

Wessex Archaeology Aircraft Crash Sites at Sea A Scoping Study Archaeological Desk-based Assessment Ref: 66641.02 February 2008 AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES AT SEA: A SCOPING STUDY ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT:FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park Salisbury WILTSHIRE SP4 6EB Prepared for: English Heritage February 2008 Ref: 66641.02 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2008 Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No.28778 Aircraft Crash Sites at Sea: A Scoping Study Wessex Archaeology 66641.02 AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES AT SEA: A SCOPING STUDY ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK-BASED ASSESSMENT:FINAL REPORT Ref: 66641.02 Summary Wessex Archaeology have been funded by English Heritage through the Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund to undertake a scoping study to identify current gaps in data and understanding relating to aircraft crash sites at sea. The study arises partly out of the discovery of aircraft parts and associated human remains as a result of marine aggregate dredging. The objectives of the Scoping Study are as follows: x to review existing literature relating to the archaeology of aircraft crash sites at sea, existing guidance, and the legislative context; x to clarify the range and archaeological potential of aircraft crash sites, by presenting examples of aircraft crash sites, which will include a range of site conditions and mechanisms affecting site survival, their management and investigation; x to establish the relationship, in terms of numbers and composition, between the National Monuments Record -

Number 7 SMITHSONIAN ANNALS of FLIGHT SMITHSONIAN AIR

Number 7 SMITHSONIAN ANNALS OF FLIGHT SMITHSONIAN AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM & SERIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION The emphasis upon publications as a means of diffusing knowledge was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In his formal plan for the Insti tution, Joseph Henry articulated a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This keynote of basic research has been adhered to over the years in the issuance of thousands of titles in serial publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Annals of Flight Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the research and collections of its several museums and offices and of professional colleagues at other institutions of learning. These papers report newly acquired facts, synoptic interpretations of data, or original theory in specialized fields. These pub lications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, laboratories, and other interested institutions and specialists throughout the world. Individual copies may be obtained from the Smithsonian Institution Press as long as stocks are available. S. DILLON RIPLEY Secretary Smithsonian Institution The Curtiss D-12 Aero Engine Curtiss D-12-E engine, 435 hp, 1930. -

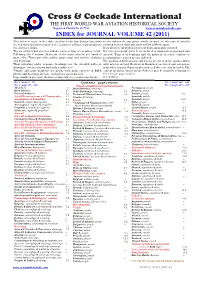

Vol 42 Index

Cross & Cockade International THE FIRST WORLD WAR AVIATION HISTORICAL SOCIETY Registered Charity No 1117741 www.crossandcockade.com INDEX for JOURNAL VOLUME 42 (2011) This index is made in the style established by Ray Sanger but using to the subject in any given article or part, in the case of articles the indexing facility included in the computer software now producing running to more than one issue will be indexed again. the Journal layouts. Data given in tabulations have not been separately indexed. The serial list index also has added a name or type of aeroplane in list. References to people have been confined to important personages and Following the Contents, Abstracts of the main articles are listed in aircrew. Targets of bombing and the position of aerial combats or page order. These give title, author, page range and number of photos reconnaissance sorties are not indexed. and drawings. The authors of both articles and letters are given in the Author Index Then following under separate headings are the detailed subjects, with articles in bold. Reviews in Bookshelf are listed and references drawings, covers, reviews and author indices etc. from other regular departments such as Fabric are also included. The Volume and page numbers are given, with main subjects in bold, context in which entries in the Subjects may be found by referring to photos and drawings in italic, with photos given priority. the relevant page number. Page numbers give only the first of what may be a series of reference Derek Riley No. 1 -page 1 – 72 Contents page.column No. -

Model Builder April 1988

AT LAST! A R.E.A.L. FAIL SAFE SYSTEM APR IL 1988 ICO 08545 U.S.A $2.95 Canada $3.95 volume 18, number 195 WORLD'S MOST COMPLETE MODEL PUBLICATION CONSTRUCTION riist (Lamssfe O X DQJJEPCLEISS VANGUARD TAKES THE LEAD. Airtronics’ new Vanguard Series crystals for rapid frequency changes. leads the way in R/C systems with The Vanguard radio design is fully top of the line appearance, features compatible with all Aiitronics’ and performance, at a down to quality accessories, servos and earth price. radio systems. The affordable Vanguard VG4R Airtronics’ Vanguard Series radios and VG6DR incorporate the same offer outstanding features at an craftsmanship, quality and state of affordable price, superior perform the art component technology of ance and Airtronics’ full one-year our more expensive radio systems. include servo reversing for easier limited warranty. Tbp quality precision gimbals installation, high quality recharge Thke the lead with Vanguard and give you the feel and control of able NiCd batteries and a Balanced put the competition in its place. our most advanced aircraft radios. Mixer receiver for superior noise Fully adjustable length and tension and image rejection. sticks allow for accurate control The Vanguard 4 and 6 channel ^AIRTRONICS me response. The VG6DR also offers 11 Autry, Irvine, Ca. 92718(714)830-8769 Dual Rate elevator and aileron controls and electronic trims for At Airtronics, we want to be known maximum aircraft, performance. as the best, not ju st the best known. The functionally designed Vanguard radios look as good as they perform. Vanguard features N e w b o o k “briefings ” fr o m H .A . -

134-60 July/Aug

ISSUE #134-60 July/Aug. 1990 Club News ~ --;: ~;,- .. ~ .. , ."JB)iGRoHJ li:'4,i!iitieri~{jjj'i.iii1t;YiiltieS'Pf48CWiiiiiJuoFd·1titeiceptor~i/'··. ...&M....."'""'J 2., Let's start with the cover as usual Clubsters. This one is a copy of an old .vintage '408 Fuller Paint series of pencil sketches sent in to us by Jack Little. ,Tack has these for sale but he didn't include the price. So we will have to wait till next time on that. Jhanks Jack. Now how many modelers does it take to put --on a good fun-filled contest? Not many, just a hand full will do. But when you get a record turnout like we had at the FAC-NATS Mark VII you just have to call it Utopia! The weather for the most part was very good, just·~a couple of brief showers on Sunday, the folks at the museum gave great cooperation and the food on the field was exce llent which was provided by the local Kiwanis Club. Everything at the college worked out fine, too. This issue is filled with the results of the contest. For those of you who do not care to read contest results please bear with us as we have some great things coming up in the next few issues. ~e only have one plan for you this time, too, as we just do not have space for any more. We are going to have two OF three .. Nata v{inning -p±ansuuf1Jr--YOU-;--~-"-"--'''- Now to the awards. Grand Champion is Jack McGillivray. Jack had a great weelcend of flying.