Byram River V. Village of Port Chester: Winning Is Not Enough

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIS Impervious Surface Final Report

PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT Mapping and Monitoring Changes in Impervious Surfaces in the Long Island Sound Watershed March 2006 James D. Hurd, Research Associate Daniel L. Civco, Principal Investigator Sandy Prisloe, Co-Investigator Chester Arnold, Co-Investigator Center for Land use Education And Research (CLEAR) Department of Natural Resources Management & Engineering College of Agriculture and Natural Resources The University of Connecticut Storrs, CT 06269-4087 Table of Contents Introduction . 4 Study Area and Data . 5 Land Cover Classification . 7 Sub-pixel Classification Overview . 8 Initial Sub-pixel Classification . 10 Post-classification Processing . 10 Validation . 13 Reseults and Discussion. 15 References . 18 Appendix A: Per Pixel Comparison of Planimetric and Estimated Percent Impervious Surfaces .. 21 Appendix B: Comparison of Planimetric and Estimated Percent Impervious Surfaces Summarized Over Grid Cells of Various Sizes. 34 Appendix C: Summary of Impervious Surfaces per Sub-regional Watershed . 46 Appendix D: Table of Deliverables . 56 i List of Figures Figure 1. Hydrologic impact of urbanization flowchart . 5 Figure 2. Study area . 6 Figure 3. Examples of land cover for 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2002 . 8 Figure 4. IMAGINE Sub-pixel Classifier process . 9 Figure 5. Examples of raw impervious surface estimates for 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2002 11 Figure 6. Examples of final impervious surface estimates for 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2002 14 Figure A-1. 1990 West Hartford validation data (area 1) and difference graph . 22 Figure A-2. 1990 West Hartford validation data (area 2) and difference graph . 23 Figure A-3. 1995 Marlborough validation data and difference graph . 24 Figure A-4. 1995 Waterford validation data (area 1) and difference graph . -

Harbor Watch | 2016

Harbor Watch | 2016 Fairfield County River Report: 2016 Sarah C. Crosby Nicole L. Cantatore Joshua R. Cooper Peter J. Fraboni Harbor Watch, Earthplace Inc., Westport, CT 06880 This report includes data on: Byram River, Farm Creek, Mianus River, Mill River, Noroton River, Norwalk River, Poplar Plains Brook, Rooster River, Sasco Brook, and Saugatuck River Acknowledgements The authors with to thank Jessica Ganim, Fiona Lunt, Alexandra Morrison, Ken Philipson, Keith Roche, Natalie Smith, and Corrine Vietorisz for their assistance with data collection and laboratory analysis. Funding for this research was generously provided by Jeniam Foundation, Social Venture Partners of Connecticut, Copps Island Oysters, Atlantic Clam Farms, 11th Hour Racing Foundation, City of Norwalk, Coastwise Boatworks, Environmental Professionals’ Organization of Connecticut, Fairfield County’s Community Foundation, General Reinsurance, Hillard Bloom Shellfish, Horizon Foundation, Insight Tutors, King Industries, Long Island Sound Futures Fund, McCance Family Foundation, New Canaan Community Foundation, Newman’s Own Foundation, Norwalk Cove Marina, Norwalk River Watershed Association, NRG – Devon, Palmer’s Market, Pramer Fuel, Resnick Advisors, Rex Marine Center, Soundsurfer Foundation, Town of Fairfield, Town of Ridgefield, Town of Westport, Town of Wilton, Trout Unlimited – Mianus Chapter. Additional support was provided by the generosity of individual donors. This report should be cited as: S.C. Crosby, N.L. Cantatore, J.R. Cooper, and P.J. Fraboni. 2016. Fairfield -

CT2030 2020-2030 Base SOGR Investment $10.341 $0.023 $5.786

Public Transportation Total Roadway Bus Rail ($B) ($B) ($B) CT2030 2020-2030 Base SOGR Investment $10.341 $0.023 $5.786 $16.149 2020-2030 Enhancement Investment $3.867 $0.249 $1.721 $5.837 Total $14.208 $0.272 $7.506 $21.986 Less Allowance for Efficiencies $0.300 CT2030 Program total $21.686 Notes: 2020-2030 Base SOGR Investment Dollars for Roadway also includes funding for bridge inspection, highway operations center, load ratings 2020-2030 program includes "mixed" projects that have both SOGR and Enhancement components. PROJECT ROUTE TOWN DESCRIPTION PROJECT COST PROJECT TYPE SOGR $ 0014-0185 I-95 BRANFORD NHS - Replace Br 00196 o/ US 1 18,186,775 SOGR 100% $ 18,186,775 0014-0186 CT 146 BRANFORD Seawall Replacement 7,200,000 SOGR 100% $ 7,200,000 0015-0339 CT 130 BRIDGEPORT Rehab Br 02475 o/ Pequonnock River (Phase 2) 20,000,000 SOGR 100% $ 20,000,000 0015-0381 CT 8 BRIDGEPORT Replace Highway Signs & Supports 10,000,000 SOGR 100% $ 10,000,000 0036-0203 CT 8 Derby-Seymour Resurfacing, Bridge Rehab & Safety Improvements 85,200,000 SOGR 100% $ 85,200,000 0172-0477 Various DISTRICT 2 Horizontal Curve Signs & Pavement. Markings 6,225,000 SOGR 100% $ 6,225,000 0172-0473 CT 9 & 17 DISTRICT 2 Replace Highway Signs & Sign Supports 11,500,000 SOGR 100% $ 11,500,000 0172-0490 Various DISTRICT 2 Replace Highway Signs & Supports 15,500,000 SOGR 100% $ 15,500,000 0172-0450 Various DISTRICT 2 Signal Replacements for APS Upgrade 5,522,170 SOGR 100% $ 5,522,170 0173-0496 I-95/U.S. -

RTM Districts

DISTRICT NO. 1- SOUTH CENTER Bounded on the north by the center of the Boston Post Road; on the east by the center of Brothers Brook: on The south by the center of the Metro-North Railroad; On the west by the center of Prospect Street from the Metro-North Railroad northerly to the Boston Post Road. DISTRICT NO. 2 - HARBOR Bounded on the north by the center of the Boston Post Road from Brothers Brook to the Mianus River; on the east by the center of the Mianus River and the center of Cos Cob Harbor and a line south from the center of the entrance of Cos Cob Harbor in Long Island Sound; on the south by the southern boundaryof the Town of Greenwich in Long Island Sound from a line south of Cos Cob Harbor to a line south from the Metro-North Railroad underpass at Hamilton Avenue; on the west by a line from Long Island Sound directly north to Metro-North Railroad underpass at Hamilton Avenue, thence easterly along the center of the Metro-North Railroad from the underpass at Hamilton Avenue, to the center of Brothers Brook, thence northerly along the center of Brothers Brook to the Boston Post Road. DISTRICT NO. 3- CHICKAHOMINY Bounded on the north by the center of the Boston Post Road from Western Junior Highway to Prospect Street; on the east by the center of Prospect Street southerly to the Metro-North Railroad; on the south by the center of the Metro-North Railroad to the underpass at Hamilton Avenue and thence northerly on a direct line to the intersection of Richland Road and Western Junior Highway, thence on the center of Western Junior Highway to the Boston Post Road. -

Byram, Connecticut an Historic Qesc~Urces Inventory

Byram, Connecticut An Historic Qesc~urcesInventory State National Bank of Connecticut has underwritten the cost of printing this Presentation Edition of The History of Byram to be sent to major donors to the capital gift fund of Byram Archibald Neighborhood House in grateful acknowledgement of the importance of their gift to all the people of our community. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE THE HISTORY OF BYKAM BIBLIOGRAPHY PREFACE I The Historic R.esources Inventory of Byram was funded by the Greenwich Community Development Program through a grant from the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The opinions and contents herein are the responsibility of the consultants, Renee Kahn Associates, and do not necessarily represent the opinions or position of the Town of Greenwich, the Greenwich Community Development Program, or the U. 5. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The data reflects the information available to the consultants at the time of the stludy, and is subject to revision as new sources appear. We would like to express our thanks to the many people whose assistance and knowledge made this project possible. Credit for the initiation of this study goes to Nancy C. Brown, Director of the Greenwich Community Development Program. Especially helpful was Alice Dutton, who provided historical information and rare, old photographs. Also assisting us with photographic information were Tad Taylor, June Curley, Yvonne Marchfelder, and John Carrott. Other historic information was provided by George Frey, Nancy Reynolds, and the many Byram residents who volunteered information on their corn munity , neighbor hoods, and homes. Also helpful in our research were the staffs of the Assessor's Office, the Town Clerk's Office, and the Planning and Zoning Commission, all of the Town of Greenwich, the Greenwich Library, the Port Chester Library, and the entire staff of the Greenwich Community Development Program. -

Connecticut Watersheds

Percent Impervious Surface Summaries for Watersheds CONNECTICUT WATERSHEDS Name Number Acres 1985 %IS 1990 %IS 1995 %IS 2002 %IS ABBEY BROOK 4204 4,927.62 2.32 2.64 2.76 3.02 ALLYN BROOK 4605 3,506.46 2.99 3.30 3.50 3.96 ANDRUS BROOK 6003 1,373.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.09 ANGUILLA BROOK 2101 7,891.33 3.13 3.50 3.78 4.29 ASH CREEK 7106 9,813.00 34.15 35.49 36.34 37.47 ASHAWAY RIVER 1003 3,283.88 3.89 4.17 4.41 4.96 ASPETUCK RIVER 7202 14,754.18 2.97 3.17 3.31 3.61 BALL POND BROOK 6402 4,850.50 3.98 4.67 4.87 5.10 BANTAM RIVER 6705 25,732.28 2.22 2.40 2.46 2.55 BARTLETT BROOK 3902 5,956.12 1.31 1.41 1.45 1.49 BASS BROOK 4401 6,659.35 19.10 20.97 21.72 22.77 BEACON HILL BROOK 6918 6,537.60 4.24 5.18 5.46 6.14 BEAVER BROOK 3802 5,008.24 1.13 1.22 1.24 1.27 BEAVER BROOK 3804 7,252.67 2.18 2.38 2.52 2.67 BEAVER BROOK 4803 5,343.77 0.88 0.93 0.94 0.95 BEAVER POND BROOK 6913 3,572.59 16.11 19.23 20.76 21.79 BELCHER BROOK 4601 5,305.22 6.74 8.05 8.39 9.36 BIGELOW BROOK 3203 18,734.99 1.40 1.46 1.51 1.54 BILLINGS BROOK 3605 3,790.12 1.33 1.48 1.51 1.56 BLACK HALL RIVER 4021 3,532.28 3.47 3.82 4.04 4.26 BLACKBERRY RIVER 6100 17,341.03 2.51 2.73 2.83 3.00 BLACKLEDGE RIVER 4707 16,680.11 2.82 3.02 3.16 3.34 BLACKWELL BROOK 3711 18,011.26 1.53 1.65 1.70 1.77 BLADENS RIVER 6919 6,874.43 4.70 5.57 5.79 6.32 BOG HOLLOW BROOK 6014 4,189.36 0.46 0.49 0.50 0.51 BOGGS POND BROOK 6602 4,184.91 7.22 7.78 8.41 8.89 BOOTH HILL BROOK 7104 3,257.81 8.54 9.36 10.02 10.55 BRANCH BROOK 6910 14,494.87 2.05 2.34 2.39 2.48 BRANFORD RIVER 5111 15,586.31 8.03 8.94 9.33 9.74 -

New York State Coastal Management Program and Final Environmental

NEW YORK STATE COASTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAM AND FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT This document incorporates all of the approved routine program changes from 1982 to 2020. Prepared by: Office of Coastal Zone Management National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Department Of Commerce 3300 Whitehaven Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20235 and New York Department of State 99 Washington Avenue, Suite1010 Albany, New York 12231‐0001 The preparation of this publication was financed in part through the office of Coastal Zone Management, NOAA. DESIGNATION: Final Environmental Impact Statement TITLE: Proposed Federal Approval of the New York Coastal Program ABSTRACT: The State of New York has submitted its Coastal Program to the Office of Coastal Zone Management for approval. Approval would allow program administrative grants to be awarded to the State, and would require that Federal actions be consistent with the program. This document includes a copy of the program (Volume 1), which is a comprehensive management program for coastal land and water use activities. It consists of numerous policies on diverse management issues which are administered under existing State laws and is the culmination of several years of program development. New York’s coastal policies either: promote the beneficial use of coastal resources, prevent their impairment, or deal with major activities that substantially affect numerous resources. The program will improve decision-making processes used for determining the appropriateness of actions in the coastal area. Approval and implementation of the program will enhance governance of the State’s coastal land and water areas and uses according to the coastal policies and standards contained in the existing statutes, authorities and rules. -

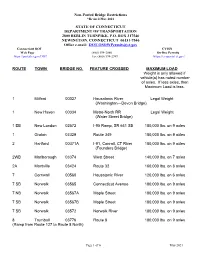

Indivisibleloadpermitbridgerest

Non-Posted Bridge Restrictions *Revised May 2021 STATE OF CONNECTICUT DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 2800 BERLIN TURNPIKE, P.O. BOX 317546 NEWINGTON, CONNECTICUT 06131-7546 Office e-mail: [email protected] Connecticut DOT CVISN Web Page (860) 594-2880 On-line Permits https://portal.ct.gov/DOT Fax (860) 594-2949 https://cvoportal.ct.gov/ ROUTE TOWN BRIDGE NO. FEATURE CROSSED MAXIMUM LOAD Weight is only allowed if vehicle(s) has noted number of axles. If less axles, then Maximum Load is less. 1 Milford 00327 Housatonic River Legal Weight (Washington—Devon Bridge) 1 New Haven 00334 Metro-North RR Legal Weight (Water Street Bridge) 1 EB New London 02572 I-95 Ramp, SR 641 SB 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles 1 Groton 03329 Route 349 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles 2 Hartford 00371A I-91, Conrail, CT River 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles (Founders Bridge) 2WB Marlborough 03374 West Street 140,000 lbs. on 7 axles 2A Montville 03424 Route 32 160,000 lbs. on 8 axles 7 Cornwall 00560 Housatonic River 120,000 lbs. on 6 axles 7 SB Norwalk 03565 Connecticut Avenue 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles 7 NB Norwalk 03567A Maple Street 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles 7 SB Norwalk 03567B Maple Street 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles 7 SB Norwalk 03572 Norwalk River 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles 8 Trumbull 03776 Route 8 180,000 lbs. on 9 axles (Ramp from Route 127 to Route 8 North) Page 1 of 6 May 2021 8 SB Shelton 02720 Armstrong Road 180,000 lbs. -

Harbor Management Plan.” the Meaning and Use of These Terms May Differ in Town, State, and Federal Laws, Regulations, and Ordinances

APPENDICES APPENDIX A: GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDIX B: SOURCES OF INFORMATION APPENDIX C: SPECIAL LEGISLATIVE ACTS 288 AND 93 APPENDIX D: CONNECTICUT HARBOR MANAGEMENT ACT APPENDIX E: HARBOR MANAGEMENT COMMISSION ORDINANCE APPENDIX F: TOWN CHARTER ARTICLE 19 DIVISION 2: HARBOR REGULATIONS APPENDIX G: GREENWICH MUNICIPAL CODE CHAPTER 7: PARKS AND RECREATION APPENDIX H: TOWN RULES AND REGULATIONS FOR GREENWICH HARBOR AND COS COB HARBOR APPENDIX I: CORPS OF ENGINEERS GUIDELINES FOR PLACEMENT OF FIXED AND FLOATING STRUCTURES IN WATERS OF THE U.S. A-1 Appendix A: Glossary of Harbor Management Terms1 Abandoned Vessel: Any vessel, as defined by state statute, not moored, anchored or made fast to the shore, and left unattended for a period greater than 24 hours, or left upon private property without consent from the waterfront property owner for a period greater than 24 hours. Active Recreational Use: Recreational uses generally requiring facilities and organization for participation and/or having a more significant impact on the natural environment than passive recreational uses. Adverse Visual Impacts: The negative impacts, described by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection’s Office of Long Island Sound Programs (DEEP OLISP) in the Fact Sheet “Landscape Protection and Visual Impacts,” that occur when the character, quality, or public enjoyment of a visual resource such as the Greenwich Harbors Area is diminished or impaired as a result of changes in the appearance of the landscape caused by developments in water and on the shoreline. Aesthetic Resources: The aesthetic coastal resources described in Sec. 22a-91(5) of the Connecticut Coastal Management Act and which, pursuant to the Act, are to be protected from adverse impacts that include, but are not limited to, actions that would degrade visual quality through significant alteration of the natural features of vistas and viewpoints. -

Schenob Brook

Sages Ravine Brook Schenob BrookSchenob Brook Housatonic River Valley Brook Moore Brook Connecticut River North Canaan Watchaug Brook Scantic RiverScantic River Whiting River Doolittle Lake Brook Muddy Brook Quinebaug River Blackberry River Hartland East Branch Salmon Brook Somers Union Colebrook East Branch Salmon Brook Lebanon Brook Fivemile RiverRocky Brook Blackberry RiverBlackberry River English Neighborhood Brook Sandy BrookSandy Brook Muddy Brook Freshwater Brook Ellis Brook Spruce Swamp Creek Connecticut River Furnace Brook Freshwater Brook Furnace Brook Suffield Scantic RiverScantic River Roaring Brook Bigelow Brook Salisbury Housatonic River Scantic River Gulf Stream Bigelow Brook Norfolk East Branch Farmington RiverWest Branch Salmon Brook Enfield Stafford Muddy BrookMuddy Brook Factory Brook Hollenbeck River Abbey Brook Roaring Brook Woodstock Wangum Lake Brook Still River Granby Edson BrookEdson Brook Thompson Factory Brook Still River Stony Brook Stony Brook Stony Brook Crystal Lake Brook Wangum Lake Brook Middle RiverMiddle River Sucker BrookSalmon Creek Abbey Brook Salmon Creek Mad RiverMad River East Granby French RiverFrench River Hall Meadow Brook Willimantic River Barkhamsted Connecticut River Fenton River Mill Brook Salmon Creek West Branch Salmon Brook Connecticut River Still River Salmon BrookSalmon Brook Thompson Brook Still River Canaan Brown Brook Winchester Broad BrookBroad Brook Bigelow Brook Bungee Brook Little RiverLittle River Fivemile River West Branch Farmington River Windsor Locks Willimantic River First -

Establishing Nitrogen Endpoints for Three Long Island Sound Watershed Groupings: Embayments, Large Riverine Systems, and Western Long Island Sound Open Water

Establishing Nitrogen Endpoints for Three Long Island Sound Watershed Groupings: Embayments, Large Riverine Systems, and Western Long Island Sound Open Water Subtask B. Regulated Point Source Discharges Submitted to: Submitted by: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Tetra Tech, Inc. Region 1 and Long Island Sound Office March 27, 2018 Establishing N Endpoints for LIS Watershed Groupings Subtask B. Regulated Point Source Discharges This Tetra Tech technical study was commissioned by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to synthesize and analyze water quality data to assess nitrogen-related water quality conditions in Long Island Sound and its embayments, based on the best scientific information reasonably available. This study is neither a proposed TMDL, nor proposed water quality criteria, nor recommended criteria. The study is not a regulation, and is not guidance, and cannot impose legally binding requirements on EPA, States, Tribes, or the regulated community, and might not apply to a particular situation or circumstance. Rather, it is intended as a source of relevant information to be used by water quality managers, at their discretion, in developing nitrogen reduction strategies. B-i Establishing N Endpoints for LIS Watershed Groupings Subtask B. Regulated Point Source Discharges Subtask B. Regulated Point Source Discharges Contents Introduction and Methods Overview .................................................................................................... B-1 Traditional Point Sources .................................................................................................................. -

Connecticut Sea Grant Project Report

1 CONNECTICUT SEA GRANT PROJECT REPORT Please complete this progress or final report form and return by the date indicated in the emailed progress report request from the Connecticut Sea Grant College Program. Fill in the requested information using your word processor (i.e., Microsoft Word), and e-mail the completed form to Dr. Syma Ebbin [email protected], Research Coordinator, Connecticut Sea Grant College Program. Do NOT mail or fax hard copies. Please try to address the specific sections below. If applicable, you can attach files of electronic publications when you return the form. If you have questions, please call Syma Ebbin at (860) 405-9278. Please fill out all of the following that apply to your specific research or development project. Pay particular attention to goals, accomplishments, benefits, impacts and publications, where applicable. Project #: __R/CE-34-CTNY__ Check one: [ ] Progress Report [ x ] Final report Duration (dates) of entire project, including extensions: From [March 1, 2013] to [August 28, 2015 ]. Project Title or Topic: Comparative analysis and model development for determining the susceptibility to eutrophication of Long Island Sound embayment. Principal Investigator(s) and Affiliation(s): 1. Jamie Vaudrey, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 2. Charles Yarish, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 3. Jang Kyun Kim, Department of Marine Sciences, University of Connecticut 4. Christopher Pickerell, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County 5. Lorne Brousseau, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County A. COLLABORATORS AND PARTNERS: (List any additional organizations or partners involved in the project.) Justin Eddings, Marine Program, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County Michael Sautkulis, Cornell Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County Veronica Ortiz, University of Connecticut Jeniam Foundation (Tripp Killin, Exec.