Thesis Book Langr.Pdf (14.86Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

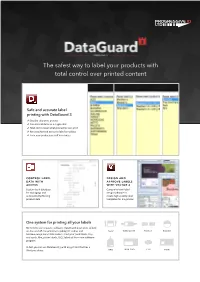

Dataguard 3 Product Overview

The safest way to label your products with Total control over printed content Safe and accurate label printing with DataGuard 3 Step-by-step print process Calculate all dates in a single-click Total control over what production can print No unauthorised access to label templates Train new production staff in minutes control label design and data with approve labels access with vector 6 Custom-built database Comprehensive label for managing and design software to create automatically filtering high-quality label product data templates for any printer One system for printing all your labels No need to use separate software, DataGuard 3 can print to both on-line and off-line printers including ICE Zodiac and pack wineglass picker round Markem-Imaje SmartDate coders. Print your pack labels, tray end cards, film, picker labels, SSCC labels all from one software program. In fact you can use DataGuard 3 with any printer that has a Windows driver. bag box end plu film Simplicity from start to finish With a step-by-step print process you have complete control over what can be printed. Production staff simply select what needs to be printed. 1 select 2 select customer category From a list of For example the type retailers and/or of fruit based on the supermarkets that product lines that have you supply been made active 3 select 4 select product line label to print Quickly choose the Where only correct product or for approved labels that longer lists search with have been setup can our new product search be chosen feature 5 select date 6 select -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

The End of Time: the Maya Mystery of 2012

THE END OF TIME ALSO BY ANTHONY AVENI Ancient Astronomers Behind the Crystal Ball: Magic, Science and the Occult from Antiquity Through the New Age Between the Lines: The Mystery of the Giant Ground Drawings of Ancient Nasca, Peru The Book of the Year: A Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays Conversing with the Planets: How Science and Myth Invented the Cosmos Empires of Time: Calendars, Clocks and Cultures The First Americans: Where They Came From and Who They Became Foundations of New World Cultural Astronomy The Madrid Codex: New Approaches to Understanding an Ancient Maya Manuscript (with G. Vail) Nasca: Eighth Wonder of the World Skywatchers: A Revised and Updated Version of Skywatchers of Ancient Mexico Stairways to the Stars: Skywatching in Three Great Ancient Cultures Uncommon Sense: Understanding Nature’s Truths Across Time and Culture THE END OF TIME T H E Ma Y A M YS T ERY O F 2012 AN T H O N Y A V E N I UNIVERSI T Y PRESS OF COLOR A DO For Dylan © 2009 by Anthony Aveni Published by the University Press of Colorado 5589 Arapahoe Avenue, Suite 206C Boulder, Colorado 80303 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The University Press of Colorado is a proud member of the Association of American University Presses. The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State College of Denver, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, and Western State College of Colorado. -

This Peregrina's Autoethnographic Account of Walking the Camino Via De La Plata

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Waterloo's Institutional Repository This Peregrina's Autoethnographic Account of Walking the Camino Via de la Plata: A Feminist Spiritual Inquiry into Human Transformation by Kimberly Lyons A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Recreation and Leisure Studies Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 2013 © Kimberly Lyons 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This is an autoethnographic account of my 1000km journey across The Camino Via de la Plata, framed within transpersonal theory. From my personal account of a peak experience on The Way, this spiritual inquiry attempts to connect myself and the reader to insights into transformation and living through embodied writing while contributing to the exploration of personal flourishing and growth in leisure studies. This process involved moving into and through Romanyshyn’s (2007) six orphic moments found in re-search processes with soul in mind. I then unfold my journey along the Camino and deepen this inquiry by engaging literature that help to explore spiritual aspects of my journey on the Camino. Leisure inquiry frames this transpersonal peak experience in a number of ways: it is an act of empowerment (Arai, 1997), focal practice (Arai & Pedlar, 2000), resistance (Shaw, 2001, 2007), and an experience of liminality (Cody, 2012) with transformation occurring at the flux of it all. -

'Pataphilology: an Irreader

’pataphilology Before you start to read this book, take this moment to think about making a donation to punctum books, an independent non-profit press, @ https://punctumbooks.com/support/ If you’re reading the e-book, you can click on the image below to go directly to our donations site. Any amount, no matter the size, is appreciated and will help us to keep our ship of fools afloat. Contri- butions from dedicated readers will also help us to keep our commons open and to cultivate new work that can’t find a welcoming port elsewhere. Our ad- venture is not possible without your support. Vive la Open Access. Fig. 1. Hieronymus Bosch, Ship of Fools (1490–1500) ’pataphilology: an irreader. Copyright © 2018 by editors and authors. This work carries a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 International license, which means that you are free to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and you may also remix, transform and build upon the material, as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors (but not in a way that suggests the authors or punctum books endorses you and your work), you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatsoever, and that for any remixing and transformation, you distribute your rebuild under the same license. http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ First published in 2018 by punctum books, Earth, Milky Way. https://punctumbooks.com ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-81-3 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-947447-82-0 (ePDF) lccn: 2018954815 Library of Congress Cataloging Data is available from the Library of Congress Book design: Vincent W.J. -

BRG Mega Clock

BRG Mega Clock Installation and Operation Manual BRG Precision Products 600 N. River Derby, Kansas 67037 http://www.brgproducts.com [email protected] 316-788-2000 Fax: (316) 788-7080 Updated: 2/8/2021 Our mission is to offer innovative technology solutions and exceptional service. 1 Table of Contents WARRANTY AGREEMENT .................................................................................................................................... 3 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................................ 9 FEATURES AND OPTIONS ................................................................................................................................... 10 INSTALLATION OF ALUMINUM FRAMED CLOCKS .................................................................................... 12 OPERATION ............................................................................................................................................................. 13 TIME ZONE CLOCK CONFIGURATION ........................................................................................................... 15 TIME ZONE CLOCK CONFIGURATION EXAMPLES .................................................................................... 16 UP-DOWN ELAPSE TIMER CONFIGURATION ............................................................................................... 17 TIMER CONFIGURATION EXAMPLES ............................................................................................................ -

The Modern Satiric Grotesque and Its Traditions

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in General English Language and Literature 2014 The Modern Satiric Grotesque and Its Traditions John R. Clark University of South Florida Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Clark, John R., "The Modern Satiric Grotesque and Its Traditions" (2014). Literature in General. 2. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_literature_in_general/2 The Modern Satiric Grotesque And Its Traditions This page intentionally left blank The Modern Satiric Grotesque And Its Traditions JOHN R. CLARK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1991 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and· Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, John R., 1930- The modern satiric grotesque and its traditions / John R. Clark. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN: 978-0-8131-5619-4 1. Grotesque in literature. 2~ Satire-History and criticism. I. Title. PN56.G7C57 1991 809.7-dc20 90-27474 This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.@ Contents Preface vii Introduction 1Index Part I. -

Excess Deaths in Spain During the First Year of the COVID–19 Pandemic Outbreak from Age/Sex–Adjusted Death Rates

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.22.20159707; this version posted July 26, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . preprint: not peer-reviewed Excess deaths in Spain during the first year of the COVID{19 pandemic outbreak from age/sex{adjusted death rates Jos´eMar´ıaMart´ın-Olalla∗ Universidad de Sevilla. Facultad de F´ısica. Departamento de F´ısicade la Materia Condensada. ES41012 Sevilla. Spain (Dated: 20210725.2046+0200) Background: The COVID{19 has been related to anomalously large excess deaths worldwide. The assessment of excess deaths is a key magnitude to quantify the overall impact of a pandemic. It requires a comprehensive statistical treatment of mortality which includes age and sex disaggregation. Methods: Weekly deaths data in Spain since the year 2000 disaggregated by sex and five{year age group, and Spanish population since the year 2000 have been used to compute the 52{week (364{day) age/sex{specific mortality rates and age/sex{adjusted mortality rates. Generalized linear Poisson regressions have been used to compute the contrafactual expected rates after one year of the pandemic onset and, from that, to compute excess rates. Results: For the past continued 13 years the year to year age/sex{adjusted death rates had not been the rate observed on February 28th, 2021. The excess death rate was estimated as 1:864 × 10−3 (95 % confidence interval, 1:846 × 10−3 to 1:881 × 10−3; P −score = 21:2 % and z−score = 11:9) with an unbiased standard deviation of the residuals equal to 156 × 10−6. -

Trinity Tripod, 1967-09-26

i < » Wat COKK Vol. LXVI No. 3 JTR1NITY COLLEGE, HARTFORD SEPTEMBER 26, 2967 Fire Safety Code Compels Renovation of Quad Dorms "The installation of the corri- summoned the architectural aid which the Jarvis, Northam and dor was absolutely mandatory." of Jeter and Cook. A letter from Cook dormitories fall, require that stated Construction Director El- city officials which arrived in early thare be two points of egress wood P. Harrison regarding the June gave the College until the from each bedroom into two self- costly and startling summer re- opening of school in September to contained stairwells. The fire novation which has come to be comply with city fire regulations. codes are highly technical, Har- known as the Rape of Jarvis. The fire regulations, under (Continued on Page 6) The interior alteration of Jar- vis, Northam and Cook dorms to meet the specifications of the Hart- ford fire codes necessitated crash construction which severely cut Community Academics the living area in the Jarvis rooms, the College's largest single unit dormitory. Additionally, the in- Organized by Students stallation of an encased stairwell in Cook eliminated two single bed- Co-operative education has been bers. rooms. defined by its practitioners at "free The traditional student-teacher The major renovation, for which universities" across the country in relationship is reversed within the College had to borrow a re- terms of curricular freedom, de- the co-operative system. Classes ported $320,000, caught the admin- mocratic structure, non-authori- are chaired by students rafter istrators completely by surprise tarian technique of teaching, and than teachers, and students are last May. -

Dataguard 3 Product Overview

The safest way to label your products with total control over printed content Safe and accurate label printing with DataGuard 3 � Step-by-step print process � Calculate all dates in a single-click � Total control over what production can print � No unauthorised access to label templates � Train new production staff in minutes control label design and data with approve labels access with vector 6 Custom-built database Comprehensive label for managing and design software to automatically filtering create high-quality label product data templates for any printer One system for printing all your labels No need to use separate software, DataGuard 3 can print to both on-line and off-line printers including ICE Zodiac and pack wineglass picker round Markem-Imaje SmartDate coders. Print your pack labels, tray end cards, film, picker labels, SSCC labels all from one software program. In fact you can use DataGuard 3 with any printer that has a Windows driver. bag box end plu film Simplicity from start to finish With a step-by-step print process you have complete control over what can be printed. Production staff simply select what needs to be printed. 1 select 2 select customer category From a list of retailers For example the type and/or supermarkets of fruit based on the that you supply product lines that have been made active 3 select 4 select product line label to print Quickly choose the Where only approved correct product or for labels that have been longer lists search with setup can be chosen our new product search feature 5 select date -

Daniel Pinchbeck

2012 the return of quetzalcoatl . Daniel Pinchbeck JEREMY P. TARCHER/PENGUIN a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. New York JEREMY P. TARCHER/PENGUIN Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0745, Auckland, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First trade paperback edition 2007 Copyright © 2006 by Daniel Pinchbeck Afterword © 2007 by Daniel Pinchbeck Some material from 2012: The Return of Quetzalcoatl appeared previously, in modified form, in Arthur, Black Book, and The Guardian Weekend magazines. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions. The author gratefully acknowledges permission to quote from: Excerpt from “The Hollow Men” in Collected Poems (1909–1962) by T. -

Textual Cultures

TEXTUAL CULTURES Texts, Contexts, Interpretation 8:1 S Editor-in-Chief: D E. O’S Editor: E B Editor: M W Editor: H A Editor: A B Editor: J A. W Editor: M Z Editor: D D P Founding Editor: H. W S Board of Editorial Advisors: G B , University of Michigan J B , University of Shefeld M B , Princeton University P G C , University of Texas, Arlington J C C , Oxford University T D R , Università di Firenze O G , New York University P G , University of Chicago D. C. G , City University of New York D K, Yale University J J. M G, University of Virginia R M , University of Washington B O , Princeton University P S , Loyola University, Chicago M N S , University of Maryland G. T T, John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation R T , Univerisité de Paris IV (Sorbonne) Textual Cultures 8.1 Contents Daniel E. O’Sullivan Stepping Back and Leaping Forward 1 EDITING OPTIONS H. Wayne Storey Mobile Texts and Local Options: Geography and Editing 6 Dirk Van Hulle The Stuff of Fiction: Digital Editing, Multiple Drafts and the Extended Mind 23 CROSSED CODES: PRINT’S DREAM OF THE DIGITAL AGE, DIGITAL’S MEMORY OF THE AGE OF PRINT, CUR ATED BY M ARTA WERNER Jonathan Baillehache Chance Operations and Randomizers in Avant-garde and Electronic Poetry: Tying Media to Language 38 Gabrielle Dean “Every Man His Own Publisher”: Extra-Illustration and the Dream of the Universal Library 57 Charity Hancock, Clifford Hichar, Carlea Holl-Jensen, Kari Kraus, Cameron Mozafari, and Kathryn Skutlin Bibliocircuitry and the Design of the Alien Everyday 72 Andrew Ferguson Mirror World, Minus World: Glitching Nabokov’s Pale Fire 101 BOOK R EVIEWS, EDITED BY HEATHER A LLEN R , José.