Oral History Interview with George Rickey, 1965 July 17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rickey, George CV 08 08 19

Marlborough GEORGE RICKEY 1907— Born in South Bend, Indiana 2002— Died in Saint Paul, Minnesota on July 17, 2002 EDUCATION 1929— BA, Modern History, Balliol College, Oxford, England Académie L’hôte and Académie Moderne, Paris, France (through 1930) 1941— MA, Modern History, Balliol College, Oxford, England 1945— Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, New York, New York (through 1946) 1947— Studied etching under Mauricio Lasansky, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa 1948— Institute of Design, Chicago, Illinois (through 1950) SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017— George Rickey: Sculpture from the Estate, Marlborough Fine Art, London, United Kingdom 2016— George Rickey: Selected Works from the Estate 1954-2000, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2015— George Rickey: Esculturas, Galeria Marlborough, Barcelona, Spain 2013— George Rickey - Sculpture from the Estate, Marlborough Gallery, New York, New York 2012— George Rickey, Galerie Michael Haas, Berlin, Germany 2011— The Art of a Kinetic Sculptor, Sculpture in the Streets, Albany, New York (through 2012) George RickeyGalerie Michael Haas, Berlin, Germany Marlborough George Rickey Indoor/Outdoor, Maxwell Davidson Gallery, New York, NY 2010— George Rickey: Important Works from the Estate, Marlborough Chelsea, New York, New York 2009— George Rickey: An Evolution, Arts Council, Cultural Development Commission and the City of Indianapolis, Indianapolis, Indiana A Life in Art: Works by George Rickey, Indianapolis Art Center, Indianapolis, Indiana Innovation: George Rickey Kinetic Sculpture, a series -

06.04.2019–11.08.2019, ZKM Atrium 1+2 Negative Space Trajectories Of

06.04.2019–11.08.2019, ZKM Atrium 1+2 Negative Space Trajectories of Sculpture February 2019 Negative Space The last exhibition, which dealt comprehensively with the question Trajectories of Sculpture “What is modern sculpture?”, took place in 1986 at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris under the title »”Qu'est-ce que la sculp- Duration of exhibition ture moderne?”. The exhibition Negative Space at ZKM | Karlsruhe 06.04.–11.08.2019 picks up the spear where the Centre Pompidou dropped it. Location ZKM Atrium 1+2 Since antiquity, the history of Western sculpture has been closely Press preview linked to the idea of the body. Whether carved, modeled or cast, Thur, 04.04.2019, 11 am statues have been designed for centuries as solid monoliths – as Opening Fri, 05.04.2019, 7 pm., ZKM Foyer substantial and self-contained entities, as more or less powerful and weighty positive formations in space. Our expectations con- Press contact cerning modern or contemporary sculpture are still essentially driv- Regina Hock en by the concept of body sculpture, which is formally based on Press officer Tel: 0721 / 8100 – 1821 the three essential categories of mass, unbroken volume, and grav- ity. Whether body-related like Auguste Rodin's or abstract like E-Mail: [email protected] www.zkm.de/presse Richard Serra's, sculpture is still and foremost mass, volume, and gravity. ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe Lorenzstraße 19 76135 Karlsruhe The exhibition Negative Space endeavors to change the dominat- ing view of modern and contemporary sculpture by telling a differ- Founders of the ZKM ent story. -

20 Recent Sculptures Will Be Shipped to England

/(To THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART 11 WEST 53 STREET. NEW YORK 19. N. Y. & g^ TELEPHONE: CIRCLE 5-8900 Thursday, April h, I963 Twenty recent sculptures selected by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, will be shipped to England on April 12 at the request of the London County Council for the famovs open-air exhibition in Battersea Park, The invitation from the London County Council marks the first time that another country has been invited to participate on such a large scale in this official municipal show which has been held every three years since 19^8. The exhibition will be on view from the middle of May through the summer. The United States representation is being sent under the auspices of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art. As only works suitable for outdoor exhibition could be chosen, the selection is not a complete survey. The great variety of new forms, new techniques and materials and range of expression which characterizes recent American sculpture is, however, clearly indicated. Work ranges from a life-size bronze cast of a man by Leonard Baekin to a sculpture of welded auto metal by Jason Seley and includes carved wood by Raoul Hague, fired clay by Peter Voulkos, a sheet steel stabile by Alexander Calder and a kinetic or moving sculpture by George Rickey. With the exception of a 1^9 copper sculpture by Jose" de Rivera, all the work dates from the 60s. Reuben Nakian i9 represented by a seven foot high bronze, Herbert Ferberrs copper sculpture is almost eight feet high and David Smith's steel piece is almost flina feet high* Other artists whose work is being sent are: Seymour Lipton, Peter Agostini, Harry Bertoia, John Chamberlain, Joseph Goto, Dimitri Hadzi, Philip Pavia, James Rosati, Julius Schmidt and Richard Stankiewicz. -

Richard Kostelanetz

Other Works by Richard Kostelanetz Fifty Untitled Constructivst Fictions (1991); Constructs Five (1991); Books Authored Flipping (1991); Constructs Six (1991); Two Intervals (1991); Parallel Intervals (1991) The Theatre of Mixed Means (1968); Master Minds (1969); Visual Lan guage (1970); In the Beginning (1971); The End of Intelligent Writing (1974); I Articulations/Short Fictions (1974); Recyclings, Volume One (1974); Openings & Closings (1975); Portraits from Memory (1975); Audiotapes Constructs (1975); Numbers: Poems & Stories (1975); Modulations/ Extrapolate/Come Here (1975); Illuminations (1977); One Night Stood Experimental Prose (1976); Openings & Closings (1976); Foreshortenings (1977); Word sand (1978); ConstructsTwo (1978); “The End” Appendix/ & Other Stories (1977); Praying to the Lord (1977, 1981); Asdescent/ “The End” Essentials (1979); Twenties in the Sixties (1979); And So Forth Anacatabasis (1978); Invocations (1981); Seductions (1981); The Gos (1979); More Short Fictions (1980); Metamorphosis in the Arts (1980); pels/Die Evangelien (1982); Relationships (1983); The Eight Nights of The Old Poetries and the New (19 81); Reincarnations (1981); Autobiogra Hanukah (1983);Two German Horspiel (1983);New York City (1984); phies (1981); Arenas/Fields/Pitches/Turfs (1982); Epiphanies (1983); ASpecial Time (1985); Le Bateau Ivre/The Drunken Boat (1986); Resume American Imaginations (1983); Recyclings (1984); Autobiographicn New (1988); Onomatopoeia (1988); Carnival of the Animals (1988); Ameri York Berlin (1986); The Old Fictions -

David Smith's Equivalence Michael Schreyach Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Art and Art History Faculty Research Art and Art History Department 2007 David Smith's Equivalence Michael Schreyach Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/art_faculty Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Repository Citation Michael Schreyach, “David Smith’s Equivalence” in The Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation Collection (Los Angeles, 2007): 212-13. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Art and Art History Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. David Smith Ame1ican, 1906-1965 Attists of David Smith's generation often sought to produce artworks that challenged the conven tions of artistic "expression" and the expectations-technical, formal, psychological, interpreta tive-that accompanied them. Smith (like his contempormies Stumt Davis, Willem de Kooning, and Arshile Gorky) was one of a group of artists whose formal innovations were guided both by a desire to align themselves with avant-garde art and by a pressing need to distance themselves from European affiliation.In Barnett Newman's words, these aitists wanted to liberate themselves from "the impediments ... of Western European painting" in order to "create images whose reality is self-evident and which are devoid of the props and crutches" of European culture.1 A technical innovator, among other things, Smith would eventually become one of the first American mtists to use welding as an art form in the 1930s. -

George Rickey Kinetic Sculptures

GEORGE RICKEY KINETIC SCULPTURES SAMUEL VANHOEGAERDEN GALLERY SAMUEL VANHOEGAERDEN GALLERY GEORGE RICKEY 1907-2002 George and Edie Rickey, Berlin, 1978 GEORGE RICKEY KINETIC SCULPTURES AUGUST 6 – SEPTEMBER 18, 2016 SAMUEL VANHOEGAERDEN GALLERY – KNOKKE – 2016 Zeedijk 720 – 8300 Knokke – Belgium www.svhgallery.be – [email protected] SHORT BIOGRAPHY George Rickey was born on June 6, 1907 in South Bend, Indiana, of New England heritage. The third of six children, and only boy, he moved to Scotland in 1913 with his parents and sisters. He spent his formative years at Glenalmond, a boarding school near Perth. He always attributed his love for learning to his years there, and on graduation was accepted at Oxford where he studied Modern History at Balliol College, with frequent visits to the Ruskin School of Drawing. Following his heart, and against the advice of his father, upon graduating he spent the following year in Paris, studying at Académie L’Hote and Académie Moderne, while earning his keep as an English instructor at the Gardiner School. In Paris he met Endicott Peabody, Rector at Groton School, Massachusetts, who offered him a job as history teacher at Groton, where he remained for three years after his return to the States in 1930. He maintained an art studio in New York from 1934 to 1942, when he was drafted. In 1947 he married Edith (Edie) Leighton (died 1995); they had two sons: Stuart, b. 1953, and Philip, b. 1959. The son of a mechanical engineer and the grandson of a clockmaker, Rickey’s interest in things mechanical re- awakened during his wartime work in aircraft and gunnery systems research and maintenance. -

Iakov Chernikhov and His Time

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ IAKOV CHERNIKHOV AND THE ARCHITECTURAL CULTURE OF REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE in the School of Architecture and Interior Design of the college of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning 2002 by Irina Verkhovskaya Diploma in Architecture, Moscow Architectural Institute, Moscow, Russia 1999 Committee: John E. Hancock, Professor, M.Arch, Committee Chair Patrick A. Snadon, Associate Professor, Ph.D. Aarati Kanekar, Assistant Professor, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The subject of this research is the Constructivist movement that appeared in Soviet Russia in the 1920s. I will pursue the investigation by analyzing the work of the architect Iakov Chernikhov. About fifty public and industrial developments were built according to his designs during the 1920s and 1930s -

George Rickey

GEORGE RICKEY BORN IN SOUTH BEND, INDIANA 1907 DIED IN ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 2002 SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 “George Rickey: Monumental Sculptures on Park Avenue,” presented by The Sculpture Committee of The Fund for Park Avenue, NYC Parks’ Art in the Parks Program and Kasmin, New York, NY “George Rickey,” Kasmin Sculpture Garden, New York, NY 2019 “Breaking Column III (Public Installation),” Palmer Art Museum, Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA 2011 “The Art of a Kinetic Sculptor,” Sculpture in the Streets, Albany, NY 2009-10 “George Rickey: Arc of Development,” South Bend Museum of Art, South Bend, IN 2009 “A Life in Art: Works by George Rickey,” Indianapolis Art Center, Indianapolis, IN 2007-09 “George Rickey: Kinetic Sculpture, A Retrospective,” Vero Beach Museum of Art, Vero Beach, FL; Frederik Meijer Gardens and Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, MI and McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX 2003 “George Rickey: Kinetische Skulpturen,” Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, Hamburg, Germany 2001 “George Rickey: A Tribute,” University Art Museum, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 2000 “George Rickey,” Gallery Kasahara, Tokyo, Japan “Park Avenue Malls Planting Projects,” organized by the City of New York Parks & Recreation, New York, NY (installation of Annular Eclips V) 1999 “George Rickey: Maquettes and drawings related to Crucifera IV,” Birmingham Museum of Art, Birmingham, AL 1998 “George Rickey,” Veranneman Foundation Kruishoutem, Kruishoutem, Belgium 1993 “A Dialogue in Steel and Air: George Rickey,” Philharmonic Center -

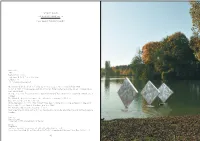

GEORGE RICKEY Three Squares Vertical Diagonal II

GEORGE RICKEY South Bend 1907 – 2002 Saint Paul Three Squares Vertical Diagonal II stainless steel 1986 height 129 cm / 51 in. each square 91 .5 x 91 .5 cm / 36 x 36 in. numbered 1/3 only 2 sculptures were executed Originally intended to be an edition of 3, but only two were executed. No. 1/3 was finished in 1986, no. 2/3 in 1988. 3/3 was never executed and according to Rickey’s wishes never will be, since no sculptures can be made after his death. There are two versions: Three Squares Vertical Diagonal , 1978 and Three Squares Vertical Diagonal II , 1986 (the present sculpture) They differ in the dimensions: the squares of the earlier version measure 60 in./ 152.4 cm, those of the second version 36 in./ 91 .4 cm. Of the larger version, no. 2/3 is in East Chatham Estate, the artist’s former studio. Another example of this large version has been at the Benesse Art Site in Naoshima, Japan since 1989. No. 2/3 of the smaller version is in a private collection. The George Rickey Workshop and the archive of the estate have certified the authenticity of the work and the provenance in writing. Provenance - Studio of the artist - Private collection ( 1986, acquired directly from the artist) Literature Other version: - Art Center of South Bend. George Rickey in South Bend. South Bend 1985, p. 13, ill. - Merkert, Jörn / Prinz, Ursula. George Rickey in Berlin 1967- 1992, Die Sammlung der Berlinischen Galerie. Berlin 1992, p. 14, ill. 80 Motivated by David Smith’s steel sculptures and As the title indicates, Three Squares Vertical Diago - Alexander Calder’s mobiles, George Rickey turned nal II is the second version of this constellation that his attention to kinetic objects in 1945. -

Biennial Report 2015–2016

Biennial Report 2015–2016 1 2 Biennial Report 2015–2016 3 Dish with Everted Rim and Design of Squirrels amidst Grapevines, late 17th–early 18th century; Qing dynasty, Chinese, Jingdezhen ware: porcelain with underglaze cobalt blue decoration; 3 7/8 × 16 1/4 inches; Museum Purchase, by exchange 60:2016 4 Report of the President It is my great pleasure to acknowledge and thank The independent review of credit-rating agencies 2014-15 Board President Barbara B. Taylor for continued to recognize the Museum for its sound her service and extraordinary commitment to the financial management. In 2016, Moody’s reaffirmed Saint Louis Art Museum. Following the first full year the Museum’s Aa3 bond rating, and Standard & Poor’s of operating its expanded campus, the Museum began reaffirmed the institution’s A+ debt rating and revised 2015 under Barbara’s leadership focused on the its outlook on the Museum from stable to positive. advancement of a new five-year strategic plan adopted by the Board of Commissioners in August 2014. As of December 31, 2016, the market value of the With an emphasis on the institution’s long-term financial Museum’s endowment was $196 million. Several sustainability and underscored by a commitment to significant gifts to the endowment were received enhance significantly the institution’s digital capabilities, during the period, including an extraordinary gift the Plan prioritizes the Museum’s comprehensive to endow and name the directorship of the Museum, collection; the visitor experience; the Museum’s believed to be the largest such endowment gift to an relationship to the community; and the development art museum in the nation. -

Year of Exhib. Dates of Exhibition Title Of

File #1: File #2: File #3a: File #4: Installation Year of Exhib. Dates of Exhibition Title of Exhibition Objects/Installation Publications Press Background Photography 1941 June 5-September 1 Painting Today and Yesterday in the U.S Yes Yes Yes No Yes Masterpieces of Ancient China from Jan 1941 October 19-November 23 Kleijkamp Collection ? Yes ? ? No Arts of America Before Columbus: 500 B.C. - 1942 April 18-June AD 1500 (Ancient American Art) ? Yes Yes ? Yes United Nations Festival and Free France Exhibit Lent by Mr. & Mrs. Walter Arensberg and 1942 May Edward G. Robinson. ? No Yes ? No 1942 July 1-July 31 Modern Mexican Painters Yes Yes ? ? No Five Centuries of Painting lent by Jacob 1943 March 7-April 11 Heimann ? No ? ? No Paintings, Sculpture, and Lithographs by Arnold 1943 June Ronnebeck No No Yes No 1943 October 3 - ? America in the War. No Yes No 1943 November 16-December 7 Paintings by Agnes Pelton ? No ? ? No 1944 February 9-March 12 Paintings and Drawings by Jack Gage Stark ? Yes ? ? No Annual Exhibition of the California Watercolor 1944 March 15-April 7 Society Yes Yes ? ? No 1944 April 8-April 30 Paintings by Hilaire Hiler Yes No ? ? No 1944 July 8-July 23 Abstract and Surrealist Art in the United States ? Yes ? ? No 1944 September 5-October 5 First Annual National Competitive Exhibition ? Yes ? ? No Chinese Sculpture from the I to XII Centuries A.D. from the collection of Jan Kleijkamp and Ellis Monro. (“12 Centuries of Sculpture from Yes (Call# China”) Rare NB 1944 October-November 26 ? 1043.S3) ??No Charlotte Berend: Exhibition of Paintings in Oil 1944 November 9-December 10 and Watercolor ?Yes??No 1945 March 11- The Debt to Nature of Art and Education ? Yes ? ? No Memorial Exhibition: "Philosophical & 1945 March 15-April 11 Allegorical" Paintings by Spencer Kellogg, Jr. -

David Smith Papers

David Smith papers Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... David Smith papers AAA.smitdavp Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: David Smith papers Identifier: AAA.smitdavp Date: 1926-1965 Creator: Smith, David, 1906-1965 Extent: 6 Microfilm reels Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Lent for microfilming by Rebecca and Candida Smith. Other Finding Aids Finding aid available at Archives of American Art offices. Available Formats 35mm microfilm reels NDSmith 1-NDSmith 6 available for