Complete Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali-Pakistan

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 10: 41-48. 2006. Check List of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali-Pakistan Mushtaq Ahmad, Mir Ajab Khan, Shabana Manzoor, Muhammad Zafar And Shazia Sultana Department of Biological Sciences, Quaid-I-Azam University Islamabad-Pakistan Issued 15 February 2006 ABSTRACT The research work was conducted in the selected areas of Isakhel, Mianwali. The study was focused for documentation of traditional knowledge of local people about use of native medicinal plants as ethnomedicines. The method followed for documentation of indigenous knowledge was based on questionnaire. The interviews were held in local community, to investigate local people and knowledgeable persons, who are the main user of medicinal plants. The ethnomedicinal data on 55 plant species belonging to 52 genera of 30 families were recorded during field trips from six remote villages of the area. The check list and ethnomedicinal inventory was developed alphabetically by botanical name, followed by local name, family, part used and ethnomedicinal uses. Plant specimens were collected, identified, preserved, mounted and voucher was deposited in the Department of Botany, University of Arid Agriculture Rawalpindi, for future references. Key words: Checklist, medicinal flora and Mianwali-Pakistan. INTRODUCTION District Mianwali derives its name from a local Saint, Mian Ali who had a small hamlet in the 16th century which came to be called Mianwali after his name (on the eastern bank of Indus). The area was a part of Bannu district. The district lies between the 32-10º to 33-15º, north latitudes and 71-08º to 71-57º east longitudes. The district is bounded on the north by district of NWFP and Attock district of Punjab, on the east by Kohat districts, on the south by Bhakkar district of Punjab and on the west by Lakki, Karak and Dera Ismail Khan District of NWFP again. -

List of Canidates for Recuritment of Mali at Police College Sihala

LIST OF CANIDATES FOR RECURITMENT OF MALI AT POLICE COLLEGE SIHALA not Sr. No Sr. Name Address CNIC No CNIC age on07-04-21age Remarks Attached Qulification Date ofBirth Date Father Name Father Appliedin Quota AppliedPost forthe Date ofTestPractical Date Home District-DomicileHome Affidavit attached / Not Not Affidavit/ attached Day Month Year Experienceor Certificate attached 1 Ghanzafar Abbas Khadim Hussain Chak Rohacre Teshil & Dist. Muzaffargarh Mali Open M. 32304-7071542-9 Middle 01-01-86 7 4 35 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 W. No. 2 Mohallah Churakil Wala Mouza 2 Mohroz Khan Javaid iqbal Pirhar Sharqi Tehsil Kot Abddu Dist. Mali Open M. 32303-8012130-5 Middle 12-09-92 26 7 28 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Muzaffargarh Ghulam Rasool Ward No. 14 F Mohallah Canal Colony 3 Muhammad Waseem Mali Open M. 32303-6730051-9 Matric 01-12-96 7 5 24 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Khan Tehsil Kot Addu Dist. Muzaffargrah Muhammad Kamran Usman Koryia P-O Khas Tehsil & Dist. 4 Rasheed Ahmad Mali Open M. 32304-0582657-7 F.A 01-08-95 7 9 25 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Rasheed Muzaffargrah Muhammad Imran Mouza Gul Qam Nashtoi Tehsil &Dist. 5 Ghulam Sarwar Mali Open M. 32304-1221941-3 Middle 12-04-88 26 0 33 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Sarwar Muzaffargrah Nohinwali, PO Sharif Chajra, Tehsil 7 6 Mujahid Abbas Abid Hussain Mali Open M. 32304-8508933-9 Matric 02-03-91 6 2 30 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 District Muzaffargarh. Hafiz Ali Chah Suerywala Pittal kot adu, Tehsil & 7 Muhammad Akram Mali Disable 32303-2255820-5 Middle 01-01-82 7 4 39 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Mumammad District Muzaffargarh. -

Journal of Sustainability Perspectives Namal Institute

Journal of Sustainability Perspectives: Special Issue, 2021, 319-325 Journal of Sustainability Perspectives journal homepage: https://ejournal2.undip.ac.id/index.php/jsp/ Namal Institute: A Mission for Rural Uplift, Sustainable Development, and Social Impact Yasir Riaz1, * 1Namal Institute, 30 KM Talagang Road, Mianwali, Pakistan, *corresponding author: [email protected] Article Info Abstract Namal Institute was established by Mr. Imran Khan, a famous philanthropist and the current Prime Minister of Pakistan, with a mission Received: for rural uplift and development through educating bright youth and 15 March 2021 offering innovative solutions to rural challenges through research by highly Accepted: trained academics. The majority of the Namal’s students belong to rural 25 May 2021 areas, and 97% of them secured scholarship either due to meritorious Published: educational background or being unable to afford education (i.e., need- 1 August 2021 based scholarship). To ensure quality, Namal has kept a student-faculty ratio of 10:1. It is one of the pioneering institutes focusing on Agribusiness DOI: and Agri-tech education in Pakistan. It has a beautiful campus comprising of 1000 Acres land located in the Salt Range in an area consisting of hills and crags overlooking Namal Lake in the Mianwali District. To foster its Presented in The 6th sustainability efforts, Namal has planted an olive garden on an area of 4 International (Virtual) acres. Recently, two new blocks have been constructed using environment- Workshop on UI GreenMetric friendly material (e.g., mud blocks, solar-powered LED lights, etc.). Various World University Rankings student societies in Namal Institute have also taken different (IWGM 2020) environmental and social initiatives in the rural area. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Mianwali

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT MIANWALI AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ....................................................... i PREFACE .................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ................................................. vii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics .................................................... vii Table 2: Audit observation regarding Financial Management .... vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ........................................................ vii Table 4: Irregularities Pointed Out ............................................. viii Table 5: Cost-Benefit ................................................................. viii CHAPTER-1 .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 District Government Mianwali................................................ 1 1.1.1 Introduction of Departments ................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ...... 1 1.1.3 Brief Comments on the Status of MFDAC Audit Paras of Audit Report 2015-16.............................................................. 3 1.1.4 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance with PAC Directives ................................................................................ 3 1.2 -

Checklist of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 10: 41-48. 2006. Check List of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali-Pakistan Mushtaq Ahmad, Mir Ajab Khan, Shabana Manzoor, Muhammad Zafar And Shazia Sultana Department of Biological Sciences, Quaid-I-Azam University Islamabad-Pakistan Issued 15 February 2006 ABSTRACT The research work was conducted in the selected areas of Isakhel, Mianwali. The study was focused for documentation of traditional knowledge of local people about use of native medicinal plants as ethnomedicines. The method followed for documentation of indigenous knowledge was based on questionnaire. The interviews were held in local community, to investigate local people and knowledgeable persons, who are the main user of medicinal plants. The ethnomedicinal data on 55 plant species belonging to 52 genera of 30 families were recorded during field trips from six remote villages of the area. The check list and ethnomedicinal inventory was developed alphabetically by botanical name, followed by local name, family, part used and ethnomedicinal uses. Plant specimens were collected, identified, preserved, mounted and voucher was deposited in the Department of Botany, University of Arid Agriculture Rawalpindi, for future references. Key words: Checklist, medicinal flora and Mianwali-Pakistan. INTRODUCTION District Mianwali derives its name from a local Saint, Mian Ali who had a small hamlet in the 16th century which came to be called Mianwali after his name (on the eastern bank of Indus). The area was a part of Bannu district. The district lies between the 32-10º to 33-15º, north latitudes and 71-08º to 71-57º east longitudes. The district is bounded on the north by district of NWFP and Attock district of Punjab, on the east by Kohat districts, on the south by Bhakkar district of Punjab and on the west by Lakki, Karak and Dera Ismail Khan District of NWFP again. -

Bahaal Emergency Relief & Early Recovery for the Flood Affectees Across Pakistan 2010-2011 National Rural Support Programme (Nrsp)

BAHAAL EMERGENCY RELIEF & EARLY RECOVERY FOR THE FLOOD AFFECTEES ACROSS PAKISTAN 2010-2011 NATIONAL RURAL SUPPORT PROGRAMME (NRSP) Written and Edited by Ali Anis Contents NRSP .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Vision and Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 3 Objective ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Bahaal Project ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Need ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Objective ............................................................................................................................................... 5 Goal: ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Target Areas .............................................................................................................................................. 6 Activities ................................................................................................................................................... -

Rural Poverty Reduction Through Social Mobilization the Union

N R S P Rural Poverty Reduction through Social Mobilization The Union Council Poverty Reduction Plan (UC Plan) Local Support Organizations (LSOs) – Kamar Mashani, Tehsil Isa Khel, District Mianwali, Punjab, Pakistan Progress Report as of November 2009 BY Akhlaq Hussain and Salma Khalid National Rural Support Programme 46 – Aga Khan Road, F – 6/4, Islamabad, Pakistan T: +92 51 2822319, 2822324 Fax: +92 51 2822779 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nrsp.org.pk Table of Contents Background__________________________________________________________________ 3 UC Kamar Mushani and Management Arrangements ________________________________ 4 Selection Criteria __________________________________________________________________ 4 Union Council Kamar Mashani _______________________________________________________ 5 UC Plan Kamar Mashani ____________________________________________________________ 5 Progress of Kamar Mashani UC Plan______________________________________________ 7 Capacity Building of Community Resource Persons _______________________________________ 7 Quantitative Achievements__________________________________________________________ 8 Target wise consolidated report of Achievements in UC___________________________________________ 9 Progress before and after the start of the UC Plan ______________________________________________ 11 Activity wise Analysis_________________________________________________________ 12 Activity 1.1 Village Development Plans _______________________________________________ 12 Activity 1.2 Situation analysis -

IEE Report for Conversion of Existing Grid Station & Construction of 132Kv Transmission Line FESCO

Initial Environmental Examination September 2012 MFF 0021-PAK: Power Distribution Enhancement Investment Program – Proposed Tranche 3 Prepared by Faisalabad Electric Supply Company for the Asian Development Bank. Draft Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Report Project Number: F7&F11 {September-2012} Islamic Republic of Pakistan: Power Distribution Enhancement Investment Program (Multi-tranche Financing Facility) Tranche-III: Conversion of 66Kv Existing Grid Station Kala Bagh into 132Kv Grid Station & Construction of Double Circuit 132Kv Transmission Line from Jinnah Hydropower-220Kv Daud Khel In & Out Kala Bagh Grid Station Prepared by: Faisalabad Electric Supply Company (FESCO) Government of Pakistan The Initial Environmental Examination Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB‟s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 1.1. Overview & Background ................................................................................................. 1 1.2. Requirements for Environmental Assessment ............................................................ 2 1.3. Scope of the IEE Study and Personnel ......................................................................... 4 1.4. Structure of Report .......................................................................................................... 5 -

Details of Optic Fibre Cable (OFC) Nodes

Details of Optic Fibre Cable (OFC) Nodes S.No PROVINCE DISTRICT TEHSIL LOCATION OF OFC NODE 1 BALOCHISTAN AWARAN AWARAN AWARAN 2 BALOCHISTAN AWARAN JHAL JHAO JHAL JHAO 3 BALOCHISTAN BARKHAN BARKHAN BARKHAN 4 BALOCHISTAN BOLAN BHAG BHAG 5 BALOCHISTAN BOLAN DHADHAR DHADHAR 6 BALOCHISTAN BOLAN MACH MACH 7 BALOCHISTAN BOLAN SANNI SANNI 8 BALOCHISTAN BOLAN SANNI SHORAN 9 BALOCHISTAN CHAGHI DALBANDIN CHAGAI 10 BALOCHISTAN CHAGHI DALBANDIN DALBANDIN 11 BALOCHISTAN CHAGHI TAFTAN NOKKUNDI 12 BALOCHISTAN CHAGHI TAFTAN TAFTAN 13 BALOCHISTAN DERA BUGTI DERA BUGTI DERA BUGTI 14 BALOCHISTAN DERA BUGTI SUI SUI 15 BALOCHISTAN GWADAR GWADAR DHORE 16 BALOCHISTAN GWADAR GWADAR GWADAR 17 BALOCHISTAN GWADAR JIWANI JIWANI 18 BALOCHISTAN GWADAR ORMARA ORMARA 19 BALOCHISTAN GWADAR PASNI PASNI 20 BALOCHISTAN JAFFARABAD JHAT PAT DERA ALLAH 21 BALOCHISTAN JAFFARABAD JHAT PAT ROJHAN JAMALI 22 BALOCHISTAN JAFFARABAD USTA MOHAMMAD USTA MOHAMMAD 23 BALOCHISTAN JHAL MAGSI GANDAWA GANDAWA 24 BALOCHISTAN JHAL MAGSI JHAL MAGSI JHAL MAGSI 25 BALOCHISTAN KALAT KALAT KALAT 26 BALOCHISTAN KALAT MANGUUCHAR KHAD KOECH 27 BALOCHISTAN KALAT SURAB BAGH BANA 28 BALOCHISTAN KALAT SURAB SURAB 29 BALOCHISTAN KECH DASHT DASHT 30 BALOCHISTAN KECH KECH KALAG 31 BALOCHISTAN KECH KECH KALATUK 1 of 27 Details of Optic Fibre Cable (OFC) Nodes S.No PROVINCE DISTRICT TEHSIL LOCATION OF OFC NODE 32 BALOCHISTAN KECH KECH NASIRABAD 33 BALOCHISTAN KECH KECH NODAIZ 34 BALOCHISTAN KECH KECH PIDARAK 35 BALOCHISTAN KECH KECH TURBAT 36 BALOCHISTAN KECH TUMP BALICHAH 37 BALOCHISTAN KHARAN MASHKHEL MASHKHEL -

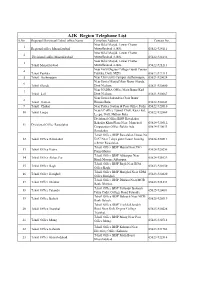

Copy of Compiled List Phone Nos BISP ALL Regions Dated 21.05

AJK Region Telephone List S.No Regioanl/Divisioanl/Tehsil office Name Complete Address Contact No. Near Bilal Masjid, Lower Chatter 1 Regional office Muzaffarabad Muzaffarabad AJ&K. 05822-924111 Near Bilal Masjid, Lower Chatter 2 Divisional office Muzaffarabad Muzaffarabad AJ&K. 05822-924132 Near Bilal Masjid, Lower Chatter 3 Tehsil Muzaffarabad Muzaffarabad AJ&K. 05822-921213 Near Girls Degree College Gandi Peeran 4 Tehsil Patikka Patikka, Distt. MZD. 05822-922113 5 Tehsil Authmaqam Near University Campus Authamaqam, 05821-920024 Near Jamia Masjid Main Bazar Sharda, 6 Tehsil Sharda Distt Neelum. 05821-920800 Near NADRA Office Main Bazar Kail 7 Tehsil kail Distt Neelum. 05821-920667 Near Jamia Sakandria Chok Bazar 8 Tehsil Hattian Hattian Bala. 05822-922643 9 Tehsil Chakar Near Police Station & Post Office Pothi 05822-922010 NearAC office Tunnel Chok, Kaser kot, 10 Tehsil Leepa 05822-922869 Leepa, Distt. Hattian Bala. Divisional Office BISP Rawalakot Bahadar Khan Plaza Near Muncipal 05824-920512, 11 Divisional Office Rawalakot Corporation Office Baldia Ada 05824-920033 Rawalakot. Tehsil Office BISP Rawalakot House No 12 Tehsil Office Rawalakot D-97 Near 7 days guest house housing 05824-920511 scheme Rawalakot. Tehsil Office BISP Hajira Near PSO 13 Tehsil Office Hajira 05824-920256 Pump Hajira. Tehsil Office BISP Abbaspur Near 14 Tehsil Office Abbas Pur 05824-921029 Hanfi Mosque Abbaspur. Tehsil Office BISP Bagh Near BDA 15 Tehsil Office Bagh 05823-920150 Office Bagh. Tehsil Office BISP Harighel Near SDM 16 Tehsil Office Harighel 05823-920820 Office Harighel. Tehsil Office BISP Dhirkot Near MCB 17 Tehsil Office Dhirkot 05823-921233 Bank Dhirkot. Tehsil Office BISP Pallandri Balouch 18 Tehsil Office Palandri 05825-920081 Palza Cadet College Road Palandri. -

Overview of Flood Waters in N.W.F.P. and Punjab Provinces, Pakistan

)" )" )" )" )" )" )" )" )" )" ¥¦¬ i !" i )" !I)" i!")" )" !" !I i !"i !" i i ii !" i !" !"!" !" Disaster coverage by the Monsoon 3 August 2010 i International Charter 'Space Rains & Flooding Overview of Flood Watersi !" i in N.W.F.P and Major Disasters'. For more !I information on the Charter, Version 1.0 !" !" which is about assisting the !I disaster relief organizations ••• and Punjab Provinces, Pakistan with multi-satellite data and • " information, visit " !" !, Glide No: www.disasterscharter.org ! Flood Analysis with MODIS Satellite Imagery Recorded on 31 July 2010 ! Ì FL-2010-000141-PAK 550000 600000 650000 700000 750000 800000 !I " Dhudial 70°0'0"E Bakka 71°0'0"EKarak 72°0'0"E Karak Tamman 0 Bannu i Khel " KotChandna 0 " " takhat )" !I" Mengan )"" !" i Thatti Talagang Bannu 33°0'0"N " nasra Ïdak Ì wazir-n !" Chakwal Nasrati )" 365000 !I " 365000 Peshawar 33°0'0"N tala KABUL !I gang ISLAMABAD Chakrala Sarai )" i Naurang Rawalpindi Wezkhel Nuwrang !" Map i Exent Deh Gandi Khan Khel Madamir Gujranwala !" Musa " Ravod isakhel Kalai Nurpur Gambila i Khel " )" Lahore !I !" Dinga !IFaisalabad )" Banuci Kalay Lilla )" Amritsar )"!I Lakki mianwali Bharwana )" 3,491m# Naushahra ")" " )" Kunjah 0 1,515m 0 Tattar Khel Mianwali!I" # Guli Jan !I 360000 Maggowal Mona Phalia 360000 Multan Depot Ì Shadia Warcha !I Khanki ¶(! Miana Kushab Pezu Gondal)" Piplan " !I )" " " Qadirabad # 1,366m )" !I !I " Daylanor Kot Harnauli piplan Bhalwal Qaidabad " Paniala " !I Kareze Nasran Balawala Tank Dab )" " wazir-s Mirza Vanike Mitha Khushab Tatai Dabara Tank "!ITank Chak Tiwana )" i Chatha Dhrema " kalur Badinkhel Paharpur Paharpur )" 0 Muhammad Banau " kot 0 )" !I !" Ledeke Gul Kheyl Roda Kot Azam Yarik Ì Jalalpur-Nao " !I Bagntu Gara Nangal 355000 Saral 355000 Hayat Kamoke Baihk Duna Sahiwal " This map presents the standing flood waters over Rakh Singh 32°0'0"N i Girsal Chiniot Zandani !" Shorko the affected Provinces of Punjab and N.W.F.P., !I32°0'0"N " i Ratali Kulachi Rata !Ii!" Pakistan following recent heavy monsoon rains. -

Efficient Modulation Scheme for Intermediate Relay-Aided Iot

applied sciences Article Efficient Modulation Scheme for Intermediate Relay-Aided IoT Networks Waleed Shahjehan 1,†, Shahid Bashir 2,†, Saleem Latteef Mohammed 3,†, Ahmed Bashar Fakhri 3,†, Adeniyi Adebayo Isaiah 4,† and Imran Khan 1,† and Peerapong Uthansakul 5,∗,† 1 Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Engineering and Technology Peshawar, Peshawar P.O.B. 814, KPK, Pakistan; [email protected] (W.S.); [email protected] (I.K.) 2 Business Studies Department, Namal Institute, 30 km Talagang Road, Mianwali 42250, Pakistan; [email protected] 3 Department of Medical Instrumentation Techniques Engineering, Electrical Engineering Technical College, Middle Technical University, Baghdad 10013, Iraq; [email protected] (S.L.M.); [email protected] (A.B.F.) 4 International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA), PBM 98, 109101, Ibadan 200001, Nigeria; [email protected] 5 School of Telecommunication Engineering, Suranaree University of Technology, Nakhon Ratchasima 30000, Thailand * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 1 March 2020; Accepted: 18 March 2020; Published: 20 March 2020 Abstract: With the surge of ubiquitous demand for high-complexity and quality mobile Internet-of-things (IoT) services, new cooperative relaying paradigms have emerged. Motivated by the long and unpredictable end-to-end communication in relay-aided IoT networks, there is a need to introduce novel modulation schemes for very low bit error rate (BER) communications. In this paper, a practical modulation mapping scheme has been proposed to reduce decoding errors. Specifically, a hybrid automatic repeat request (HARQ) system has been used with an intermediate relay to transfer a message from a source to a destination.