Social Isolation Experienced by Older People in Rural Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selattyn and Gobowen Parish Council

Selattyn and Gobowen Parish Council Clerk: Miss A Gregory Email: [email protected] Website www.selattyn-gobowenpc.org.uk Tel: 01691 829571 6th October 2016 To: Councillors You are summoned to attend a meeting of the Parish Council to be held on Wednesday 12th October 2016 at The Pavilion, Gobowen at 7pm for the transaction of business as set out in the Agenda below. Yours sincerely, Amy Gregory Clerk to the Council AGENDA 498 To receive apologies and reasons for absence 499 Disclosable Pecuniary Interests a) Declaration of any disclosable pecuniary interest in a matter to be discussed at the meeting and which is not included in the register of interests. b) To consider any applications for dispensation 500 To confirm the Minutes of the Council Meetings held on 15.09.16 501 Public Participation session - a period of 15 minutes will be set aside for the public to speak on items on the agenda. 502 Reports a) Progress Report – To consider the Clerk’s progress report. b) Other reports - To receive and consider reports from Shropshire Council elected councillors and other reports from councillors attending meetings and site visits on behalf of the parish council. c) Police reports including reported incidents, the monthly police and CCTV report. 503 Financial Matters a) Monthly statement - To approve the monthly financial statement and bank statements against bank reconciliation. b) Payments - To approve outstanding payments and payments made prior to meeting c) Income -To note income received since the last meeting. d) Budget – To consider -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Out & About the Cuts • the Olive Tree 11 • Are Telford & Wrekin

ISSUE NO. 9 March 2011 Out & About The Cuts The Olive Tree 11 Are Telford & Wrekin Retreating? 18 Care Matters Average chief exec salary tops £150k 5 CCS Carer‘s Newsletter articles 12 Cuts to Bus Services 19 Telford Care home criticised 20 Cutting £18bn from the poor hurts! 26 Telford vow over respite care closure 5 Disabled protesters kettled 19 General Misery £30m cuts proposal 3 Concerns over Welfare Reform Bill 24 New disability test is a complete mess 14 Deaf Research 10 Round-up of Shropshire cuts news 28 Discrimination in Parliament? 27 Shrewsbury County Court closure 7 DWP sluggish over benefit errors 2 Shropshire pay £370,000 for 4 new jobs 7 Egypt: disabled people protest 10 Shropshire cuts will hit every area of life 9 Employment updates from SIP 12 The Grange Day Centre Update 30 Family Information now on Facebook 19 What DLA means to me 8 Liz Carr‘s gutsy speech 21 Medical Developments Need help writing your CV? 4 Hearing loss early warning for dementia 28 NHS ‗has forgotten we‘re humans‘ 4 Long Term Conditions 9 No compulsory care insurance 17 New clues to sight loss from AMD 15 Smart technology for disabled 12 New prescription delivery service 30 The Campaign For A Fair Society 23 Therapies can moderately improve ME 27 US payday loan firms expand in Britain 25 £3.2 Cancer Centre for RSH 20 Whizz Kids need wheelchairs 24 SDN Volunteer Editor required for Your Voice 2 Personal Experience Why join SDN? 6 Recovery from Alcohol Addiction 16 What‟s On Sally‘s Snowdon Challenge 23 General Events 31 The Arts Events: Conferences etc. -

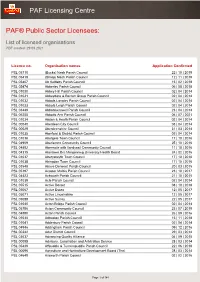

List of Licensed Organisations PDF Created: 29 09 2021

PAF Licensing Centre PAF® Public Sector Licensees: List of licensed organisations PDF created: 29 09 2021 Licence no. Organisation names Application Confirmed PSL 05710 (Bucks) Nash Parish Council 22 | 10 | 2019 PSL 05419 (Shrop) Nash Parish Council 12 | 11 | 2019 PSL 05407 Ab Kettleby Parish Council 15 | 02 | 2018 PSL 05474 Abberley Parish Council 06 | 08 | 2018 PSL 01030 Abbey Hill Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01031 Abbeydore & Bacton Group Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01032 Abbots Langley Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01033 Abbots Leigh Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 03449 Abbotskerswell Parish Council 23 | 04 | 2014 PSL 06255 Abbotts Ann Parish Council 06 | 07 | 2021 PSL 01034 Abdon & Heath Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00040 Aberdeen City Council 03 | 04 | 2014 PSL 00029 Aberdeenshire Council 31 | 03 | 2014 PSL 01035 Aberford & District Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 01036 Abergele Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04909 Aberlemno Community Council 25 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04892 Abermule with llandyssil Community Council 11 | 10 | 2016 PSL 04315 Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board 24 | 02 | 2016 PSL 01037 Aberystwyth Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 01038 Abingdon Town Council 17 | 10 | 2016 PSL 03548 Above Derwent Parish Council 20 | 03 | 2015 PSL 05197 Acaster Malbis Parish Council 23 | 10 | 2017 PSL 04423 Ackworth Parish Council 21 | 10 | 2015 PSL 01039 Acle Parish Council 02 | 04 | 2014 PSL 05515 Active Dorset 08 | 10 | 2018 PSL 05067 Active Essex 12 | 05 | 2017 PSL 05071 Active Lincolnshire 12 | 05 -

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources Available at Oswestry Library

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources available at Oswestry Library 14/01/2019 1 Revision 6 Contents Parish Registers & Monument Inscriptions 3 Trade Directories 33 Shops and Occupants Living In Oswestry 35 Electoral Registers 43 Newspapers, Magazines & Periodicals held in Oswestry Library 47 BCA Hard Copy Newspapers held in Guild Hall 47 Newspapers Alphabetical Index to Marriages & Deaths & Subject Cards 51 Parish and Village Magazines & Newsletters 53 Quarter Sessions 55 Oswestry Town Council Archive 55 Maps and Plans Field Name Maps 56 Ordnance Survey Maps 58 Other Maps 58 Tithe Apportionments 58 Printed Material 58 Photographs, Postcards and Prints 59 Parish Packs 59 Local Places Information Folders 59 Local People Information Folders 68 Media List 69 Welsh Collection 70 Fees for Weddings and Funerals circa 1768 70 14/01/2019 2 Revision 6 REGISTERS An index to Parish, Non-conformist and Roman Catholic Registers & Monumental Inscriptions held at Oswestry Library can be found below. The index indicates whether the item is available in printed form and / or on microfiche and/or digital. Parish: The registers for Oswestry and its neighbouring parishes in England and Wales are available not only in printed volumes held in the rolling stack at the library and on microfiche, but have also been put online by FindMyPast up to the year 1900 and are free to view on all library computers. Non-conformist: To find out if a non-conformist chapel or church existed in a particular area consult one of the following held in the rolling stack: Kelly's Directory, which lists chapels and Roman Catholic Churches in each parish; b) Victoria County History of Shropshire Vol. -

Out & About the Cuts • the Olive Tree 14 • Are Telford & Wrekin

ISSUE NO. 9 March 2011 Out & About The Cuts The Olive Tree 14 Are Telford & Wrekin Retreating? 25 Care Matters Average chief exec salary tops £150k 6 CCS Carer‘s Newsletter articles 16 Cuts to Bus Services 26 Telford Care home criticised 28 Cutting £18bn from the poor hurts! 35 Telford vow over respite care closure 5 Disabled protesters kettled 26 General Misery £30m cuts proposal 3 Concerns over Welfare Reform Bill 38 New disability test is a complete mess 17 Deaf Research 18 Round-up of Shropshire cuts news 41 Discrimination in Parliament? 37 Shrewsbury County Court closure 9 DWP sluggish over benefit errors 2 Shropshire pay £370,000 for 4 new jobs 11 Egypt: disabled people protest 13 Shropshire cuts will hit every area of life 12 Employment updates from SIP 15 The Grange Day Centre Update 43 Family Information now on Facebook 30 What DLA means to me 10 Liz Carr‘s gutsy speech 29 Medical Developments Need help writing your CV? 5 Hearing loss early warning for dementia 39 NHS ‗has forgotten we‘re humans‘ 4 Long Term Conditions 15 No compulsory care insurance 24 New clues to sight loss from AMD 19 Smart technology for disabled 20 New prescription delivery service 40 The Campaign For A Fair Society 32 Therapies can moderately improve ME 39 US payday loan firms expand in Britain 34 £3.2 Cancer Centre for RSH 27 Whizz Kids need wheelchairs 33 SDN Volunteer Editor required for Your Voice 2 Personal Experience Why join SDN? 7 Recovery from Alcohol Addiction 23 What‟s On Sally‘s Snowdon Challenge 31 General Events 44 The Arts Events: Conferences etc. -

Central Shropshire Walking Forum Notes of Meeting 2Pm, Friday 26Th February 2016 the Wilfred Owen Room, Shirehall, Shrewsbury At

Central Shropshire Walking Forum Notes of Meeting 2pm, Friday 26th February 2016 The Wilfred Owen Room, Shirehall, Shrewsbury Attendees: John Newnham (Chair) Shrewsbury Ramblers [email protected] Bill Hodges Shrewsbury Ramblers [email protected] Phil Barnes Shrewsbury Ramblers [email protected] Trevor Allison Shrewsbury ramblers [email protected] Anne Suffolk Telford & East Shropshire Ramblers [email protected] Naomi Wrighton Wellington WaW, Walkabout Wrekin [email protected] Dick Bailey Much Wenlock WaW & WfH [email protected] Clare Fildes Outdoor Partnerships [email protected] Mick Dunn Outdoor Partnerships [email protected] Helen Beresford Outdoor Partnerships [email protected] David Hardwick Outdoor Partnerships [email protected] Apologies: Barbara Martin Bob Coalbran Geoff Sproson Phil Wadlow 1. Welcome and Introductions John opened the meeting at 2pm 2. Feedback/Action from Previous Meeting There was no actions from the previous meeting 3. Lost Ways Project (JN) Shrewsbury Ramblers have three volunteers who would carry out research for the Lost Ways Project. If any other groups have volunteers could they please forward the names to John before the end of March so he can produce a consolidated list? Shona Butter (access & mapping team leader) will provide some training for volunteers. MD informed the meeting that the Dereg guidance due out in April has been delayed. The point of Dereg is to cut down bureaucracy and to make the legal process around ROW easier however evidence will still be required to support claims. Shona will update the forum once more details of the Dereg Bill are known. -

Hierarchy of Settlements

HoS Shropshire Council Hierarchy of Settlements CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ............................................................................ 2 2. Introduction ......................................................................................... 3 Background .........................................................................................................6 Purpose of this Document ...................................................................................6 Structure of the Documents .................................................................................6 How the Hierarchy Will Be Utilised ......................................................................6 3. The Policy Context .............................................................................. 7 National Policy ....................................................................................................7 Local Policy .........................................................................................................7 4. Methodology ........................................................................................ 8 Establishing a Methodology ................................................................................8 Principal of the Methodology ...............................................................................8 Key Stages ..........................................................................................................8 5. Assessment ........................................................................................ -

Read Points of Light 2019

0 Published by National Association of Local Councils (NALC) 109 Great Russell Street London WC1B 3LD 020 7637 1865 [email protected] www.nalc.gov.uk Unless otherwise indicated, the copyright of material in this publication is owned by NALC. Reproduction and alteration in whole or part of Points of Light 2019 is not permitted without prior consent from NALC. If you require a licence to use NALC materials in a way that is not hereby permitted or which is restricted by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, then contact NALC. Subject to written permission being given, we may attach conditions to the licence. Every effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are correct at the time of printing. NALC does not undertake any liability for any error or omission. © NALC 2019 All rights reserved. 1 CONTENTS Foreword 3 Art, culture and heritage 4 Campaigns 5 Canals and rivers 7 Cemeteries 7 Community awards 8 Community events 8 Community safety 10 Community transport 11 Community venues 14 Economic development 17 Environmental improvement 20 Flood assistance 24 Grants and funding 24 Health and wellbeing 27 Housing and planning 33 Libraries 34 Parks and open spaces 35 Partnership working 38 Playgrounds 40 Pubs 42 Street furniture 43 Winter readiness 44 Young people and youth services 44 2 FOREWORD Points of Light is a collection of case studies highlighting the work that local (parish and town) councils are undertaking to support their communities. The 2019 edition contains 150 case studies, each featuring a summary of the work carried out alongside electorate, precept and expenditure figures of the local councils involved. -

Site Allocations and Management of Development (Samdev) Development Plan Document Technical Background Paper March 2014

Site Allocations and Management of Development (SAMDev) Development Plan Document Technical Background Paper March 2014 Site Allocations and Management of Development Plan Technical Background Paper 1. Introduction Introduction Supporting documents Planning Policy context Working with others 2. Housing Housing requirements Distribution of housing Meeting the housing requirement Spatial distribution How the remaining requirement will be met Rates of growth by market town Delivery in the rural areas General Conclusion 3. Development of Settlement Strategies: Scale and location of development Constraints Albrighton Bishops Castle Bridgnorth Broseley Church Stretton Cleobury Mortimer Craven Arms Ellesmere Highley Ludlow Market Drayton Minsterley & Pontesbury Much Wenlock Oswestry Shifnal Shrewsbury Wem 2 Site Allocations and Management of Development Plan Technical Background Paper Whitchurch Site selection methodology 4. Economic Development and Employment Employment land requirements Distribution of employment Meeting the employment requirement 5. Retail Retail and Town Centre Policy Policy MD10a: Managing Town Centre Development Policy MD10b: Town and Rural Centre Impact Assessments 6. Planning approach for the Gypsies and Travellers 7. Approach to planning for Mineral Resources Aggregates and landbanks production guideline Site selection methodology; 8. Implementation and Monitoring Infrastructure delivery Infrastructure and developer contributions Infrastructure and design requirements Infrastructure and phasing of development Monitoring 3 Site Allocations and Management of Development Plan Technical Background Paper 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1.1 The purpose of this document is to set out the reasoning behind the settlement strategies and site allocations contained within the Pre Submission Draft Site Allocations and Management of Development (SAMDev) Development Plan Document. 1.2 It forms a background paper, summarising the process that has been undertaken in respect of preparing the SAMDev DPD. -

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources Available at Oswestry

A Guide to the Family and Local History Resources available at Oswestry Library 29/09/2015 1 Version 3 Contents Parish Registers & Monumental inscriptions……….……………….…………….. 3 Trade Directories ........................................................................... …………..………….. 22 Electoral Registers ................................................................................................................... 25 Newspapers & Periodicals held in Oswestry Library................................................... 27 BCA Hard Copy Newspapers held in Guild Hall ………………………………. .... 32 Newspapers Alphabetical Index to Marriages & Deaths & Subject Cards…. ...... 33 Parish and Village Magazines & Newsletters ........................................................ 35 Quarter Sessions ................................................................................................... 36 Oswestry Town Council Archive ........................................................................................... 36 Maps and Plans ..................................................................................................... 37 Field Name Maps………………………………………………………….. 37 Ordnance Survey Maps…………………………………………………… 38 Other Maps…………………………………………………………………. 38 Tithe Apportionments…………………………………………………………….. 38 Printed Material ...................................................................................................... 38 Photographs, Postcards and Prints ..................................................................................... -

December 2020

Shropshire Council Strategic Infrastructure Implementation Plan December 2020 Page 1 Table of Contents Section Description Page Introduction 1 • About the Strategic Infrastructure Implementation Plan 3 • Local Plan Review Context • Background • Shropshire Council Economic Growth Strategy 2017-21 • Shropshire Council Corporate Plan • Marches Local Enterprise Partnership – Strategic Economic Plan 2 • West Midlands Combined Authority – Strategic Economic Plan 4 • Shropshire Green Infrastructure Strategy • Shropshire Council Statement of Common Ground with Highways England • Shropshire Council Local Transport Plan 2011-26 Identifying and delivering infrastructure • How infrastructure is identified and prioritised 10 3 • How infrastructure is funded • How infrastructure is delivered Strategic Infrastructure Delivery Plan 14 4 • Introduction • Infrastructure project tables Local Plan 2016-2038: Proposed Site Allocations Infrastructure 50 5 Requirements Page 2 1. Introduction: 1.1 About the Strategic Infrastructure Implementation Plan The key document which guides development, economic growth, and infrastructure delivery in Shropshire is the Local Plan. The Local Plan considers a wide range of important planning issues such as housing, employment, retail, the environment, and transport. Shropshire Council’s Strategic Infrastructure Implementation Plan (SIIP) supports the delivery of the Local Plan. The SIIP brings together information about strategic infrastructure needs across the county – that is, infrastructure which is considered to be essential