Existential Neuropsychology: a Science of Making Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis

Modern Psychological Studies Volume 5 Number 2 Article 3 1997 An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Minier, Samuel (1997) "An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis," Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol5/iss2/3 This articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Magazines, and Newsletters at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Psychological Studies by an authorized editor of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Eclectic approaches to psychotherapy often lack cohesion due to the focus on technique and procedure rather than theory and wholeness of both the person and of the therapy. A synthesis of Jungian and existential therapies overcomes this trend by demonstrating how two theories may be meaningfully integrated The consolidation of the shared ideas among these theories reveals a notion of "authentic wholeness' that may be able to stand on its own as a therapeutic objective. Reviews of both analytical and existential psychology are given. Differences between the two are discussed, and possible reconciliation are offered. After noting common elements in these shared approaches to psychotherapy, a hypothetical therapy based in authentic wholeness is explored. Weaknesses and further possibilities conclude the proposal In the last thirty years, so-called "pop Van Dusen (1962) cautions that the differences among psychology" approaches to psychotherapy have existential theorists are vital to the understanding of effectively demonstrated the dangers of combining existentialism, that "[when] existential philosophy has disparate therapeutic elements. -

Existential Psychotherapy Societies And/Or Training Institutes List By

Existential Psychotherapy Societies and/or Training Institutes List By: Edgar Correia 1. ABILE-West Österreich 2. Akademie für Logotherapie und Existenzanalyse 3. American Association for Existential Analysis 4. Arizona Institute of Logotherapy 5. Asociación Argentina de Analisi Existencial y Logoterapia (GLE Argentina) 6. Asociación Bonaerense de Logoterapia "Por Amor a la Vida" 7. Asociación Cooperativa Viktor Frankl de Venezuela 8. Asociación Española de Logoterapia (AESLO) 9. Asociación Guatemalteca de Logoterapia 10. Asociación Latinoamericana de Psicoterapia Existencial (ALPE) 11. Asociación Peruana de Análisis Existencial y Logoterapia (APAEL) 12. Asociación Viktor E. Frankl de Valencia 13. Asociaţia Ştiinţifică Internaţională de Logoterapie şi Analiză Existenţială (LENTE) 14. Associação Brasileira de Daseinsanalyse (ABD) 15. Associação Brasileira de Logoterapia e Análise Existencial (ABLAE) 16. Associação de Logoterapia Viktor Emil Frankl (ALVEF) 17. Associació Catalana de Logoteràpia i Anàlisi Existencial (ACLAE) 18. Association de Logothérapeutes Francophones 19. Associazione di Logoterapia e Analisi Esistenziale Frankliana (ALAEF) 20. Associazione di Logoterapia Italiana (ALI) 21. Associazione Iar Esistenziale 22. Ausbildungsinstitut für Logotherapie und Existenzanalyse (ABILE) 23. Australasian Existential Society (AES) 24. Australian Section of International Society for Existential Analytical Psychotherapy (ISEAP) 25. Boulder Psychotherapy Institute (BPI) 26. Canadian Institute of Logotherapy 27. Casa Viktor Frankl 28. Center for Existential Depth Psychology (CEDP) 29. Centre et École Belge de Daseinsanalyse (CEBDA) 30. Centre for Existential Practice (CEP) 31. Centre for Research in Existence and Society 32. Centro de Anàlisis Existencial Viktor Frankl de Rosario 33. Centro de Logoterapia de Tucumán 34. Centro de Logoterapia y Análisis Existencial (CELAE) 35. Centro de Psicoterapia Existencial (CPE) 36. Centro Ecuatoriano de Análisis Existencial y Logoterapia 37. -

The Life Purpose Questionnaire: a Factor-Analytic Investigation

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 The Life Purpose Questionnaire: a Factor-Analytic Investigation Stephanie Wood Campbell Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Stephanie Wood, "The Life Purpose Questionnaire: a Factor-Analytic Investigation" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 74. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/74 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE LIFE PURPOSE QUESTIONNAIRE: A FACTOR-ANALYTIC INVESTIGATION A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Psychology The University of Mississippi by Stephanie W. Campbell August 2012 Copyright Stephanie W. Campbell 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Meaning in life has been a popular topic of philosophy and study, and the perceived presence of meaning in one’s life has been associated with many positive psychological variables (e.g., life satisfaction), while the perceived absence of meaning has been associated with negative variables (e.g., depression). The Purpose in Life test (PIL) was developed in order to assess the amount of perceived meaning in a person’s life. Despite good psychometric support, there have been questions about the structural validity of the measure (i.e., only one model has been replicated, consisting of two factors that reflect exciting life and purpose in life) as well as assertions that it is difficult to understand. -

Existential and Humanistic Theories

Existential Theories 1 RUNNING HEAD: EXISTENTIAL THEORIES Existential and Humanistic Theories Paul T. P. Wong Graduate Program in Counselling Psychology Trinity Western University In Wong, P. T. P. (2005). Existential and humanistic theories. In J. C. Thomas, & D. L. Segal (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology (pp. 192-211). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Existential Theories 2 ABSTRACT This chapter presents the historical roots of existential and humanistic theories and then describes four specific theories: European existential-phenomenological psychology, Logotherapy and existential analysis, American existential psychology and American humanistic psychology. After examining these theories, the chapter presents a reformulated existential-humanistic theory, which focuses on goal-striving for meaning and fulfillment. This meaning-centered approach to personality incorporates both negative and positive existential givens and addresses four main themes: (a) Human nature and human condition, (b) Personal growth and actualization, (c) The dynamics and structure of personality based on existential givens, and (c) The human context and positive community. The chapter then reviews selected areas of meaning-oriented research and discusses the vital role of meaning in major domains of life. Existential Theories 3 EXISTENTIAL AND HUMANISTIC THEORIES Existential and humanistic theories are as varied as the progenitors associated with them. They are also separated by philosophical disagreements and cultural differences (Spinelli, 1989, 2001). Nevertheless, they all share some fundamental assumptions about human nature and human condition that set them apart from other theories of personality. The overarching assumption is that individuals have the freedom and courage to transcend existential givens and biological/environmental influences to create their own future. -

Annotated Existential Therapies Reading List

Annotated existential therapies reading list This is a selective, and inevitably subjective, annotated list of key readings on existential therapeutic practice and philosophy. It was developed as supplementary reading for: Cooper, M (2015) Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (London: Sage). References in bold are strongly recommended. Mick Cooper, Professor of Counselling Psychology, University of Roehampton [email protected] 23rd February 2015 Introductory/general texts Adams, M. (2013). A concise introduction to existential counselling. London: Sage. Brief, practice-focused introduction to existential therapy. Barnett, L., & Madison, G. (Eds.). (2012). Existential psychotherapy: Vibrancy, legacy and dialogue. London: Routledge. Collection of papers on range of aspects of contemporary existential therapy. Cooper, M. (2003). Existential Therapies. London: Sage. Guide to the key existential approaches to therapy, exploring their key concepts, practices, commonalities and differences. Cooper, M. (2012). Existential counselling primer. Ross-on-Wye: PCCS. Concise overview of existential therapy concepts, practices and research. Correia, E., Cooper, M., & Berdondini, L. (2014). Existential Psychotherapy: An International Survey of the Key Authors and Texts Influencing Practice. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 1-8. doi: 10.1007/s10879-014-9275-y. Correia, E., Cooper, M., & Berdondini, L. (2014). The worldwide distribution and characteristics of existential psychotherapists and counsellors. Existential Analysis, 25(2), 321-337. Reviews presence and orientation of existential therapists from around the world. Correia, E., Cooper, M., & Berdondini, L. (in preparation). The practices of existential counsellors and psychotherapists. Craig, M., Vos, J., Cooper, M., & Correia, E. (in press). Existential psychotherapies. In D. Cain, K. Keenan & S. Rubin (Eds.), Humanistic psychotherapies. Washington: APA. -

A Logotherapeutic Approach to Pastoral Counseling Education for Catholic Seminarians

American Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 2019; 7(2): 43-51 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajpn doi: 10.11648/j.ajpn.20190702.13 ISSN: 2330-4243 (Print); ISSN: 2330-426X (Online) A Logotherapeutic Approach to Pastoral Counseling Education for Catholic Seminarians Joseph R. Laracy 1, 2, 3 1Department of Systematic Theology, Seton Hall University, New Jersey, USA 2Department of Catholic Studies, Seton Hall University, New Jersey, USA 3Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Seton Hall University, New Jersey, USA Email address: To cite this article: Joseph R. Laracy. A Logotherapeutic Approach to Pastoral Counseling Education for Catholic Seminarians. American Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. Vol. 7, No. 2, 2019, pp. 43-51. doi: 10.11648/j.ajpn.20190702.13 Received : May 23, 2019; Accepted : June 20, 2019; Published : July 23, 2019 Abstract: Viktor Frankl, MD, PhD is one of the most widely known and highly respected professors of psychiatry and neurology of the twentieth century. In this article, we adapt and apply some of his profound insights for Catholic pastoral counseling education. Pastoral counseling is a very important aspect of the general pastoral formation of Catholic seminarians. The goal of any pastoral counseling course should be twofold. First, it should give seminarians a basic knowledge of mental illnesses to understand their parishioners better. Second, it should offer them concrete techniques to be used in the context of pastoral counseling. Seminary classes in pastoral psychology and counseling sometimes lack a consistent, coherent theoretical foundation, or may attempt to teach techniques inappropriate for use by future parish priests. This paper presents a logotherapeutic approach for the formation of seminarians in pastoral counseling. -

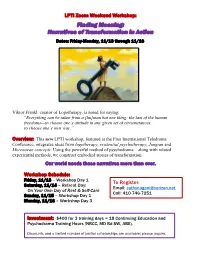

Finding Meaning: Narratives of Transformation in Action Dates: Friday-Monday, 11/13 Through 11/16

LPTI Zoom Weekend Workshop: Finding Meaning: Narratives of Transformation in Action Dates: Friday-Monday, 11/13 through 11/16 Viktor Frankl, creator of Logotherapy, is noted for saying, “Everything can be taken from a [hu]man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” Overview: This new LPTI workshop, featured at the First International Teledrama Conference, integrates ideas from logotherapy, existential psychotherapy, Jungian and Morenoean concepts. Using the powerful method of psychodrama—along with related experiential methods, we construct embodied stories of transformation. Our world needs these narratives more than ever. Workshop Schedule: Friday, 11/13 – Workshop Day 1 To Register: Saturday, 11/14 – Retreat Day: Email: [email protected] On Your Own Day of Rest & Self-Care Call: 410-746-7251 Sunday, 11/15 – Workshop Day 1 Monday, 11/16 – Workshop Day 3 Investment: $400 for 3 training days = 18 Continuing Education and Psychodrama Training Hours (NBCC, MD Bd SW, ABE). Discounts and a limited number of partial scholarships are available; please inquire. Finding Meaning: Narratives of Transformation in Action Training Objectives: At the end of this workshop, participants should be able to: ❖ Explain the significance of life narratives and narrative identity as a way of making meaning of our experience. ❖ Differentiate between a contamination/victimization narrative versus a narrative of redemption/transformation. ❖ Identify four archetypal narratives that may underlie our personal myth. ❖ Identify at least 2 holistic, integrative and experiential techniques for constructing and exploring a meaningful life narrative. Workshop Team: Catherine D. -

Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy: a Worthy Challenge

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/300077249 Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Worthy Challenge Chapter · January 2016 DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-29424-7_18 CITATIONS READS 2 4,466 1 author: Matti Ameli 5 PUBLICATIONS 25 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) View project Translation of a Logotherapy workbook on meaningful and purposeful goals. View project All content following this page was uploaded by Matti Ameli on 13 November 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Integrating Logotherapy with Cognitive Behavior Therapy: A Worthy Challenge Matti Ameli Introduction Logotherapy, developed by Victor Frankl in the 1930s, and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) , pioneered by Aaron Beck in the 1960s, present many similarities. Ameli and Dattilio ( 2013 ) offered practical ideas of how logotherapeutic tech- niques could be integrated into Beck’s model of CBT. The goal of this article is to expand those ideas and highlight the benefi ts of a logotherapy-enhanced CBT. After a detailed overview of logotherapy and CBT, their similarities and differences are discussed, along with the benefi ts of integrating them. Overview of Logotherapy Logotherapy was pioneered by the Austrian neurologist and psychiatrist Viktor Frankl (1905–1997) during the 1930s. The Viktor-Frankl-Institute in Vienna defi nes logotherapy as: “an internationally acknowledged and empirically based meaning- centered approach to psychotherapy.” It has been called the “third Viennese School of Psychotherapy” (the fi rst one being Freud’s psychoanalysis and the second Adler’s individual psychology). -

2014 February

The Society for Existential Analysis Hermeneutic FEBRUARY Circular 2014 HERMENEUTIC CIRCULAR FEBRUARY 2014 CONTENTS From The Editor 3 When The Penny Drops By Charlotte Heckscher 28 Committee Members 4 A Meditation On Love And Fear By Emma Wilkinson 29 Placebo By Charlotte Heckscher 30 Report From The Chair 6 Poems: Resilience By Ali Ross 31 A Referral to Adult ADHD Services For Diagnosis: 7 Maturation In Anxiety By Mehrshad Arshadi An Existential Phenomenological Perspective By Christos Christophy Authenticty and Bazzano By John Rowan 32 Book Review: ‘Sexuality and Gender for Mental Health 33 Reflections On Being Granted The Hans W. Cohn 8 Professionals – A Practical Guide’ by Christina Richards Scholarship By Iro Ioannou and Meg Barker By Rosemary Lodge Application of Logotherapy With Refugees 9 Second Impressions Of My First SEA Conference, 34 By Mehrshad Arshadi By An Aging Novice By Martin Barber A Conversation Between Diana Mitchell 12 News From The New School 35 And Ernesto Spinelli Society of Psychotherapy Programme 2014 35 The Sparkly Slippers: Exploring The ‘Chosen Past’ In 23 What I Offer As An Existential-Phenomenological 36 Existential Therapy By Betty Cannon & Reed Lindberg Psychotherapist? By Jonathan Hall Becoming An Existential Therapist By Emmy van deurzen 26 Crossword 38 The Society for Existential Analysis Publicity Officer Claire Marshall BM Existential Committee Member Mike Harding London Committee Member Digby Tantam WC1N 3XX Tel: 07000 394783 UKCP Registration Officer Donna Billington www.existentialanalysis.org.uk Secretary Natasha Synesiou The SEA is a Registered Charity No. 1039274 Treasurer Paola Pomponi SEA Contact Details Webmaster Haran Rasalingam Newsletter Editor Susan Iacovou Existential Analysis Editors Prof Simon du Plock, Dr Greg Madison Newsletter Design & Production Katrina Pitts Chair Dr Pavlos Filippopoulos Change of Address Please note, it is members’ responsibility to let us know of a Northern Discussion Group Organisers change of address. -

Aspects of Existential Psychotherapy in Cognitive Behavioral Approach

Romanian Journal of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Hypnosis Volume 3, Issue 3, July-September 2016 Theoretical paper Aspects of Existential Psychotherapy in Cognitive Behavioral Approach Loredana Elena Proţi Titu Maiorescu University, Bucharest, Romania Abstract The therapeutic process aims the improvement of individuals’ mental health and overall well- being through the acquirement of new relationship skills with self and the outer world. The purpose of psychotherapy is that of meeting the client’s expectations as well as possible and to guide him in the direction of his choice and desire and needs, using psychological tools. Currently there are numerous forms of psychotherapy such as psychoanalysis, schema therapy, existential psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral psychotherapy (CBT), rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), person-centered therapy (PCT), integrative psychotherapy, transactional analysis, core process therapy etc. Are there any major differences between all these forms of therapy? Which could be the best way to meet the expectations of the people who cross the thresholds of psychology cabinets? This subject can be amply debated. The present article shortly examines aspects of existential psychotherapy in the cognitive behavioral therapy, encouraging an eclectic approach. The human being is a unique complex, and this is why the best approach encouraged by researchers is the one of being opened to the client’s needs and to integrate in the therapeutic process not only specific strategies used in the forms of therapy in which the psychotherapist is specialized, but also complementary forms in order to be prepared for any challenge that can appear in the process. This way, we can serve the clients’ needs in the most complete way possible (Strieker, 1996; Gersons et al., 2000; Norcross & Goldfried, 2005). -

Applied Logotherapy for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Men and Women United States Army Veterans

Applied Logotherapy for the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Men and Women United States Army Veterans by Jenaya Rose Surcamp A PROJECT submitted to Oregon State University University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Public Health Honors Scholar Presented February 10, 2015 Commencement June 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jenaya Surcamp for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Public Health presented on February 10, 2015. Title: Applied Logotherapy for the Treatment of Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder in United States Men and Women Army Veterans. Abstract approved: ______________________________________________________ Dr. Ray Tricker This project explores the use of Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy for the treatment of post- traumatic stress disorder in a population of men and women United States Army veterans. It explores the literature surrounding this treatment, specifically Frankl’s book, Man’s Search for Meaning, and argues a clinical application for this therapy could offer the greatest relief for sufferers of this mental health condition. With the application of this treatment in this clinical setting there could be further applications of this treatment in the future within more diverse populations. Key Words: Logotherapy, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, PTSD, United States Army, Veterans, Treatment Corresponding e-mail address: [email protected] ©Copyright by Jenaya Surcamp February 10, 2015 All Rights Reserved Applied -

1 by John Firman and Ann Russell Psychosynthesis Palo Alto 461

What is Psychosynthesis? 1 WHAT IS PSYCHOSYNTHESIS? by John Firman and Ann Russell Psychosynthesis Palo Alto 461 Hawthorne Avenue Palo Alto, California 94301 U.S.A. Copyright © 1992, 1993, by John Firman and Ann Russell All rights reserved. CONTENTS Preface to the Second Edition...................................... 5 What is Psychosynthesis?............................................. 7 Assagioli’s Diagram of the Person .......................................... 8 The Middle Unconscious........................................................... 9 Lower and Higher Unconscious ............................................ 12 The Lower Unconscious .......................................................... 13 The Superconscious ................................................................. 16 “I,” Awareness, and Will ......................................................... 19 Self............................................................................................... 22 Personal Psychosynthesis ...................................................... 27 Transpersonal Psychosynthesis ............................................ 30 Self-realization.......................................................................... 34 In Conclusion ............................................................................ 38 About the Authors ........................................................ 41 Bibliography .................................................................. 41 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION This monograph was originally