NFLC Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scholarship and Teaching on Languages for Specific Purposes

Scholarship and Teaching on Languages for Specific Purposes Lourdes Sánchez-López Editor UAB Digital Collections Birmingham, Alabama, March 2013 Scholarship and Teaching on Languages for Specific Purposes ISBN 978-0-9860107-0-5 UAB Digital Collections Mervyn H. Sterne Library University of Alabama at Birmingham March 2013 Editor Lourdes Sánchez-López University of Alabama at Birmingham Production Manager Jennifer Brady University of Denver Editorial Board Julia S. Austin Clara Mojica Díaz University of Alabama at Birmingham Tennessee State University William C. Carter Malinda Blair O‘Leary University of Alabama at Birmingham University of Alabama at Birmingham Alicia Cipria Susan Spezzini University of Alabama University of Alabama at Birmingham Sheri Spaine Long Rebekah Ranew Trinh United States Air Force Academy / University of Alabama at Birmingham University of Alabama at Birmingham Lamia Ben Youssef Zayzafoon Jesús López-Peláez Casellas University of Alabama at Birmingham University of Jaén Table of Contents INTRODUCTION, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS & DEDICATION Lourdes Sánchez-López ................................................................................................................................ x ON LSP THEORETICAL MODELS Continuing Theoretical Cartography in the LSP Era Michael S. Doyle ........................................................................................................................................... 2 ON THE CURRENT STATE OF LSP Language for Specific Purposes Job Announcements from the Modern Language -

Effective Foreign Language Teaching: a Matter of Iranian Students’ and Teachers’ Beliefs

www.ccsenet.org/elt English Language Teaching Vol. 4, No. 2; June 2011 Effective Foreign Language Teaching: a Matter of Iranian Students’ and Teachers’ Beliefs Mahyar Ganjabi Payamenoor University Tel: 98-9127-049-132 E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 31, 2010 Accepted: January 28, 2011 doi:10.5539/elt.v4n2p46 Abstract This paper reports on a study that investigated the beliefs about language learning of 120 Iranian EFL students and 16 EFL teachers. The primary aim of the study was to reveal whether there was any difference between the beliefs of Iranian students and teachers regarding different aspects of language learning such as grammar teaching, error correction, culture, target language use, computer-based technology, communicative language teaching strategies and assessment. Data were collected using a 24-item questionnaire. It was concluded that there were some differences between the Iranian students’ and teachers’ beliefs regarding what procedures were most effective in bringing about language learning. Discussion of the findings and implications for further research are also articulated. Keywords: Effective language teaching, Teachers’ beliefs, Students’ beliefs 1. Introduction Language practitioners and researchers have already recognized that teachers and their agendas do not have a complete control over what learners learn from English language courses (Allwright, 1984 as cited in Breen, 2001a; Salimani, 2001). The recent emphasis on the holistic approaches to language learning have brought into our focus the fact that learners are not just cognitive beings, that is, they do not approach the task of language learning merely from the cognitive window (Breen, 2001b). But learners are multidimensional beings; they are a combination of a bulk of different variables which help them to learn whatever they are learning in the best possible way. -

García & Davis-Wiley FINAL Submission of 4-27-16 5

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 2, No. 5; November 2015 Tomorrow’s World Language Teachers: Practices, Processes, Caveats and Challenges along the Yellow Brick Road Dr. Paul A. García University of Kansas (retired) 5211 Everwood Run, Sarasota, FL 34235 U.S.A. Dr. Patricia Davis-Wiley Professor, WL and ESL ED The University of Tennessee BEC 217, Knoxville, TN 37996-3442 U.S.A. Abstract In this manuscript, the authors discuss multiple issues confronting world language teacher development (WLTD) and suggest options to ensure academic success for all world language (WL) learners. Critics’ claims that WLTD programs lack professionalization can be addressed to “get it right” for tomorrow’s pre-service students—and for their pre-K-12 learners by the establishment of a National Commission on WLTD. Four questions inform our argument that improved professionalization, together with clinical induction and teacher efficacy, will contribute to learners’ success: 1. How might WLTD build upon—and not repeat—past practices? 2. How will standardization initiatives continue to change WLTD? 3. How might investigators align research that contributes to student achievement at the pre-collegiate level? 4. How does the implementation of such endeavors influence our praxis? Keywords: post-secondary, teacher preparation and licensure, teacher characteristics 1. Prolog (nicht) im Himmel [Prologue (not) in Heaven] Pre-service teacher induction persists as a critical concern of American education. It is a generations-old societal preoccupation with teachers’ skills and preparedness, one that reformers, politicians, study groups, and teachers themselves have pilloried, studied, and reported since at least the 1850s (Goldstein, 2014). World language teacher development (WLTD) is not exempt from this history. -

Advanced Low Language Proficiency–An Achievable Goal? Aleidine Kramer Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Learning and Teacher Education Education 5-2013 Advanced Low Language Proficiency–An Achievable Goal? Aleidine Kramer Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Moeller, Aleidine Kramer, "Advanced Low Language Proficiency–An Achievable Goal?" (2013). Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education. 158. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/teachlearnfacpub/158 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: Department of Teaching, Learning and Teacher Education by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in The Modern Language Journal 97:2 (2013), pp. 549-553; doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12021.x Copyright © 2013 The Modern Language Journal; published by John Wiley Inc. Used by permission. Published online May 24, 2013 digitalcommons.unl.edu Advanced Low Language Proficiency– An Achievable Goal? Aleidine J. Moeller University of Nebraska–Lincoln A standard of language proficiency recommended of transferability have not been addressed, there- for world language preservice teachers has been fore precluding these assessments from recogni- set at advanced low as defined by the ACTFL Pro- tion by IHE. ficiency Guidelines. The National Council for the The ACTFL OPI, and WPT are the most cited Accreditation of Teacher Education (NCATE) re- and preferred measures for scholarly inquiry in quires that foreign language teacher candidates the area of language acquisition and assessment. -

Listening and Reading Proficiency

Foreign Language Annals Á VOL. 49, NO. 2 201 Listening and Reading Proficiency Levels of College Students Erwin Tschirner Universit€at Leipzig Abstract: This article examines listening and reading proficiency levels of U.S. college foreign language students at major milestones throughout their undergraduate career. Data were collected from more than 3,000 participants studying seven languages at 21 universities and colleges across the United States. The results show that while listening proficiency appears to develop more slowly, Advanced levels of reading proficiency appear to be attainable for college majors at graduation. The article examines the relationship between listening and reading proficiency and suggests reasons for the apparent disconnect between listening and reading, particularly for some languages and at lower proficiency levels. Key words: all languages, proficiency, postsecondary/higher education Introduction Despite the fact that the foreign language teaching profession has focused on oral proficiency for decades, reaching the Advanced Low (AL) level in oral proficiency has remained “an elusive endeavor” for many college graduates majoring in foreign languages, including prospective foreign language instructors (Brooks & Darhower, 2014, p. 593). According to Swender (2003, p. 523), only 47% of graduating majors at prestigious liberal arts colleges, many of whom spent an academic year abroad, were at the AL level or higher, 35% were Intermediate High (IH), and 18% were Intermediate Mid (IM) or lower. As Omaggio-Hadley (2001) noted, it may take up to 720 hours of instruction to reach the Advanced level of foreign language speaking proficiency, an amount of time that is not regularly available in an undergraduate program. -

Pursuing Distinguished Speaking Proficiency with Adult Foreign Language Learners: a Case Study by Jack Franke Dissertation Submi

i Pursuing Distinguished Speaking Proficiency with Adult Foreign Language Learners: A Case Study by Jack Franke Dissertation Submitted to the Doctoral Program of the American College of Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION March 2020 ii Pursuing Distinguished Speaking Proficiency with Adult Foreign Language Learners: A Case Study by Jack Franke Approved by: Dissertation Chair: Dr. Rita Deyoe-Chiullán, Ph. D. Committee Member: Dr. Katrina Schultz, Ed. D. Program Director: Dr. Elizabeth Johnson, Ed. D. Assistant Provost: Dr. Conna Bral, Ed. D. iii Copyright © 2020 Jack Franke iv Abstract Although study abroad is viewed in the United States as sine qua non, the study abroad experience is not a panacea to achieve distinguished foreign language speaking proficiency. This qualitative case study attempts to uncover how persistence, study abroad, motivation, and learner autonomy play in pursuit of distinguished speaking proficiency. The literature review addresses the need to investigate the efficacy of the study abroad experience vis-à-vis the students’ oral proficiency, types of motivation, and learner autonomy as a means to achieve higher speaking proficiency. Using the theoretical framework of complexity theory and phenomenological design, the proposed study utilized interviews of four educators at an institute in the Western United States as the primary instrument of data collection. This study investigates the roadmaps which successful foreign language educators have utilized to achieve distinguished speaking proficiency through interviews and documentary research. The study revealed four primary themes which are motivation, persistence, learner autonomy, and study abroad. Data analysis of interviews with the participants revealed that distinguished speaking proficiency is a highly personal pursuit, characterized by different motivations based on choice of foreign language, engagement in the target culture, grit, and time. -

Linguistics Reading List.Pdf

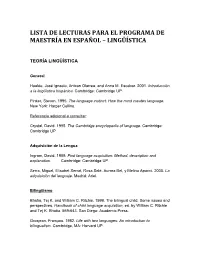

LISTA DE LECTURAS PARA EL PROGRAMA DE MAESTRÍA EN ESPAÑOL – LINGÜÍSTICA TEORÍA LINGÜÍSTICA General Hualde, José Ignacio, Antxon Olarrea, and Anna M. Escobar. 2001. Introducción a la lingüística hispánica. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. Pinker, Steven. 1995. The language instinct: How the mind creates language. New York: Harper Collins. Referencia adicional a consultar: Crystal, David. 1995. The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. Adquisición de la Lengua Ingram, David. 1989. First language acquisition: Method, description and explanation. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. Serra, Miguel, Elisabet Serrat, Rosa Solé, Aurora Bel, y Melina Aparici. 2000. La adquisición del lenguaje. Madrid: Ariel. Bilingüismo Bhatia, Tej K. and William C. Ritchie. 1999. The bilingual child: Some issues and perspectives. Handbook of child language acquisition, ed. by William C. Ritchie and Tej K. Bhatia, 569-643. San Diego: Academic Press. Grosjean, François. 1982. Life with two languages: An introduction to bilingualism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP. Grosjean, François and Ping Li. 2013. The psycholinguistics of bilingualism. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. Hakuta, Kenji. 1986. Mirror of language: The debate on bilingualism. New York: Basic Books. Hamers, Josiane F. and Michel H. A. Blanc. 1992. Bilinguality and bilingualism. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. Romaine, Suzanne. 1995. Bilingualism. 2nd ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley- Blackwell. Valdés, Guadalupe and Richard A Figueroa. 1994. Bilingualism and testing: A special case of bias. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Wei, Li. 2000. The bilingualism reader. London: Routledge. Dialectología Canfield, D. Lincoln. 1981. Spanish pronunciation in the Americas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cotton, Eleanor C. and John M. Sharp. 1988. Spanish in the Americas. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown UP. -

JELT (April-June'19)

RESVEIEAWR CPAH PPEARPSERS IMPLEMENTING AUDIO-VISUAL MATERIALS (VIDEOS), AS AN INCIDENTAL VOCABULARY LEARNING STRATEGY, IN SECOND/FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNERS' VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT: A CURRENT REVIEW OF THE MOST RECENT RESEARCH By AMIRREZA KARAMI Department of Curriculum and Instruction, University of Arkansas, USA. Date Received: 28/01/2019 Date Revised: 28/03/2019 Date Accepted: 03/06/2019 ABSTRACT Vocabulary teaching and learning has always been a difficult task for both language teachers and learners since every language learner needs to learn a large number of words for successful communication in the target language. To alleviate the vocabulary learning process, teachers and researchers are looking for new vocabulary learning strategies not only to teach vocabulary easily but also to enhance language learners' vocabulary knowledge as well. Audio-visual materials, as an incidental vocabulary learning strategy, seem to be beneficial in second/foreign language classrooms. The current literature review focuses on audio-visual materials and their effects on vocabulary learning by reviewing the most recent research studies carried out to investigate the effects of this strategy on the enhancement of vocabulary knowledge of the second/foreign language learners. To do this, three 2018 research studies from different international, peer-reviewed journals - Computer Assisted Language Learning, Language Learning & Technology, and Studies in Second Language Acquisition - were selected and discussed. The results of this literature review highlighted the positive effects of implementing audio-visual materials on vocabulary learning. The results also showed that audio-visual materials can help language learners to improve their vocabulary knowledge of the target language. The vocabulary knowledge of the second/foreign language learner can be enhanced incidentally through watching videos and hearing words in meaningful contexts and communication. -

Culture Learning in Language Education: a Review of the Literature

Culture Learning in Language Education: A Review of the Literature R. Michael Paige, Helen Jorstad, Laura Siaya, Francine Klein, Jeanette Colby INTRODUCTION This paper examines the theoretical and research literatures pertaining to culture learning in language education programs. The topic of teaching and learning culture has been a matter of considerable interest to language educators and much has been written about the role of culture in foreign language instruction over the past four decades. For insightful analyses see Morain, 1986; Grittner, 1990; Bragaw, 1991; Moore, 1991; Byram and Morgan, 1994. Most importantly, in recent years various professional associations have made significant efforts to establish culture learning standards (Standards, 1996; AATF, 1995). Yet, to date, there have been few critical reviews of the literature. In certain respects this is not surprising because culture learning is not exclusively the domain of language educators. On the contrary, the field is highly interdisciplinary in nature; contributions to the knowledge base have come from psychology, linguistics, anthropology, education, intercultural communication, and elsewhere. Moreover, anthropologists, intercultural communication scholars, and psychologists, in particular, have studied cultural phenomena quite apart from their relationship to language learning. The review confirmed what we expected: a substantial amount of important writing on culture learning exists, much of which is completely unrelated to language education. The rationale for conducting this review of the literature was to determine if studies existed which could: 1) support and/or challenge current language education practices regarding the teaching of culture, 2) provide guidance to language educators on effective culture teaching methods, 3) suggest ways to conceptualize culture in the language education context, 4) suggest ways to assess culture learning, and, 5) indicate which instructional methods are most effective for various types of culture learning objectives. -

Celeste Kinginger Curriculum Vitae

1 Celeste Kinginger Curriculum Vitae Home: Office: 1603 Ridge Road Department of Applied Linguistics Warriors Mark, PA 16877 The Pennsylvania State University 814 632-3409 305 Sparks Building [email protected] University Park, PA 16802 814 867-1373 [email protected] PERSONAL INFORMATION Current rank Professor of Applied Linguistics, Penn State University (2011 – present). Educational background University of Illinois at Urbana-CHampaign, Department of FrencH, Ph.D. Second Language Acquisition and Teacher Education. George WasHington University, WasHington, DC, M.A. FrencH Literature. AntiocH College, Yellow Springs, OHio, B.A. FrencH. Employment background Associate Professor of Applied Linguistics and FrencH, Penn State University (2002 – 2011). Director, Penn State Summer Intensive Language Institute (2001 – 2004). Assistant Professor of FrencH, Penn State University (1999 – 2001). Assistant Professor of FrencH, SoutHwest Missouri State University (1996 – 1999). Assistant Professor of FrencH, University of Maryland, College Park (1992 – 1996). 2 Acting Assistant Professor of FrencH and Foreign Language Acquisition, Stanford University (1990 – 1992). Visiting Assistant Professor of FrencH, Boston College (1988 – 1990). RESEARCH AND SCHOLARLY ACTIVITIES Books Kinginger, C. (Ed.) (2013). Social and cultural aspects of language learning in study abroad. Amsterdam: JoHn Benjamins. Kinginger, C. (2009). Language learning and study abroad: A critical reading of research. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave/Macmillan. Kinginger, C. (2008). Language learning in study abroad: Case studies of Americans in France. Modern Language Journal, 92, Monograph. Handbook Kinginger, C. (2010). Contemporary study abroad and foreign language learning: An activist’s guidebook. University Park, PA: Center for Advanced Language Proficiency Education and Research (CALPER) Publications. Articles publisHed in refereed journals Kinginger, C. & Carnine, J. -

A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES and FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION in UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS Frank Capellan Southeastern University - Lakeland

Southeastern University FireScholars College of Education Fall 2017 A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION IN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS Frank Capellan Southeastern University - Lakeland Follow this and additional works at: https://firescholars.seu.edu/coe Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, First and Second Language Acquisition Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Capellan, Frank, "A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION IN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS" (2017). College of Education. 11. https://firescholars.seu.edu/coe/11 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by FireScholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Education by an authorized administrator of FireScholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CORRELATIONAL STUDY: PERSONALITY TYPES AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACQUISITION IN UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS By FRANK CAPELLAN A doctoral dissertation submitted to the College of Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Curriculum and Instruction Southeastern University October, 2017 DEDICATION For Otilia, with everlasting love iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Over the course of my doctoral journey, I have received support and encouragement from a great number of people. I cannot fully express in words my gratitude and indebtedness to all of you for encouraging me on this long, and exhausted journey. I am deeply grateful for my dissertation committee, Dr. Joyce Tardáguila Harth, Dr. Jim Anderson, and Dr. Patricia Coronado Domenge for their incredible guidance, encouragement, and accountability throughout my research, and writing. Your counsel throughout the study process exemplified the spirit of the learning journey. -

Journal of Second Language Teaching and Research

Journal of Second Language Teaching and Research. Volume 5, Special Issue Chinese in The Classroom: Initial Findings of The Effects of Four Teaching Methods on Beginner Learners Caitríona Osborne, Dublin City University Abstract The following is an article documenting the researcher’s initial findings examining the effects of four different teaching methods on beginner CFL (Chinese as a foreign language) learners in terms of their ability to not only recall and recognize Chinese characters but also to use these characters for understanding and creating texts. The researcher is currently teaching approximately 98 students, aged 14-16, for one academic year. They are divided into four groups which each deploy a different teaching method. Depending on their groups, the participants are learning Chinese via rote memorization, delayed character introduction, character color-coding, and the method currently used in some Irish institutions, which focuses on the reading, writing, speaking and listening of Chinese as a whole. Therefore, participants in the fourth group are taught via integrated learning, without specific focus on the learning of characters as in the case of the other three groups. The outcomes of formative and summative evaluations throughout the year will highlight each group’s progression and therefore the effectiveness of each method, not only in terms of character recall and recognition, but also the use of the language. At the time of writing (November 2016), the researcher has completed approximately ten weeks of teaching (to continue until May 2017). This paper therefore presents a background to the study, a condensed literature review, methodology, preliminary findings and analysis of the first formative evaluation, and a summary of the project thus far, including correlations between theory and practice.