The Alekhine Defence Move by Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City by Norman Davies (Pp

communicated his desire to the Bishop, in inimitable fashion: MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City by Norman Davies (pp. 224-266) The Holy Ghost and I are agreed that Prelate Schaffgotsch should be coadjutor of [Bresslau] and that those of your canons who resist him shall be regarded as persons who have surrendered to the Court in Vienna and to the Devil, and, having resisted the Holy Prussia annexed Silesia in the early phase of the Enlightenment. Europe was Ghost, deserve the highest degree of damnation. turning its back on the religious bigotry of the preceding period and was entering the so-called 'Age of Reason'. What is more, Prussia was one of the The Bishop replied in kind: more tolerant of the German states. It did not permit the same degree of religious liberty that had been practised in neighbouring Poland until the late The great understanding between the Holy Ghost and Your Majesty is news to me; I was seventeenth century, but equally it did not profess the same sort of religious unaware that the acquaintance had been made. I hope that He will send the Pope and the partisanship that surrounded the Habsburgs. The Hohenzollerns of Berlin had canons the inspiration appropriate to our wishes. welcomed Huguenot refugees from France and had found a modus vivendi between Lutherans and Calvinists. In this case, the King was unsuccessful. A compromise solution had to be Yet religious life in Prussian Silesia would not lack controversy. The found whereby the papal nuncio in Warsaw was charged with Silesian affairs. annexation of a predominantly Catholic province by a predominantly But, in 1747, the King tried again and Schaffgotsch, aged only thirty-one, was Protestant kingdom was to bring special problems. -

Amateur Champion

• U. S . AMATEUR CHAMPION (S('c P. 135) • ;::. UNITED STATES VoLume XlX June, 1964 EDITOR: J . F. Reinhardt * * OFFICIAL NOTICE '" " ELECTION OF USCF STATE DIRECTORS CHESS FEDERATION Attention of aU officials of slate chess associations is directed to Article V of the USCF By-Laws, stating that " ... the State Directors shaD be certified PRESIDENT in writing to the USCF Secretary by the authorized state offiCt' r before June 30th ••." Major Edmund B. Edmondson, Jr. The number of State DirC<!tors to which each State is entitled for the year VICE·PRESIDENT beginning July 1 fo llows: David Hoffmann N.Y . ....... ...... .. ...23 FLA. .. ... ... ... ....... 4 IOWA ................ 2 KY." ... ............. 1 CALIF . .............. 23 ARIZ.- ....... ....... 4 NEBR. - ............ 2 ~IISS ................. 1 REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS PENNA. ............ 11 IND.- . ......... ...... 3 MO .· .... ..... ..... .... 2 PUERTO RICO~ 1 NEW ENGLAND ILL. ...... ... ........ 10 COLO.· .. .......... 3 KANS. ~ ............ 2 N. DAK." ........ 1 N.J . .. ..... ...... ....... 9 WASH. ........... 3 OKLA. ;' ............ 2 S. DAK. ............ 1 EASTERN Donald Schultz TEXAS ... ........... 8 VA. ............... ..... 3 N. MEX ." ..... ... 2 \\'YO.- .. ............ 1 Charln KeYltlr Peter Berlo.,.. OHIO ................ 8 LA. ..... ............ ... 3 NEV........ .... ..... 2 .lI O;"""I' ." ............ 1 MleR ......... ....... 7 D.C. ' ...... ... ... ...... 2 UTAH8 ............ 2 ARK. ...... ... ....... 1 MID·ATLANTIC MASS." ............ 6 W. VA ............. 2 MAINE" -

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (Later, in Europe, Replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS from the DR

CHESS MASTERPIECES: (later, in Europe, replaced by a HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE DR. queen). These were typically flanKed GEORGE AND VIVIAN DEAN by elephants (later to become COLLECTION bishops), though in this case, they are EXHIBITION CHECKLIST camels with drummers; cavalrymen (later to become Knights); and World Chess Hall of Fame chariots or elephants, (later to Saint Louis, Missouri 2.1. Abstract Bead anD Dart Style Set become rooKs or “castles”). A September 9, 2011-February 12, with BoarD, India, 1700s. Natural and frontline of eight foot soldiers 2012 green-stained ivory, blacK lacquer- (pawns) completed each side. work folding board with silver and mother-of-pearl. This classical Indian style is influenced by the Islamic trend toward total abstraction of the design. The pieces are all lathe- turned. The blacK lacquer finish, made in India from the husKs of the 1.1. Neresheimer French vs. lac insect, was first developed by the Germans Set anD Castle BoarD, Chinese. The intricate inlaid silver Hanau, Germany, 1905-10. Silver and grid pattern traces alternating gilded silver, ivory, diamonds, squares filled with lacy inscribed fern sapphires, pearls, amethysts, rubies, leaf designs and inlaid mother-of- and marble. pearl disKs. These decorations 2.3. Mogul Style Set with combine a grid of squares, common Presentation Case, India, 1800s. Before WWI, Neresheimer, of Hanau, to Western forms of chess, with Beryl with inset diamonds, rubies, Germany, was a leading producer of another grid of inlaid center points, and gold, wooden presentation case ornate silverware and decorative found in Japanese and Chinese clad in maroon velvet and silk-lined. -

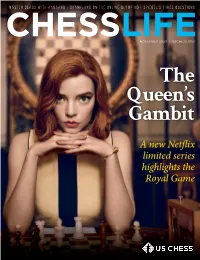

The Queen's Gambit

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

Oldies but Not Moldies (PDF)

OLDIES BUT NOT MOLDIES By Bob Basalla Probably the best way to learn anything is to do a lot of it and do it often. That certainly is true of chess where there is simply no substitute for playing lots and lots of games, serious games and fun games, slow game and speed games. There are other things that can help you learn about chess, though. One could study books about tactics, for example, or endgames, positional play and so on. The method I am going to focus on here is this: playing over master level games. One can clearly learn a lot from playing over one’s own games and those of your fellow students. (You’d get the most out of analyzing the games that you lost rather than the ones you won, but that is another article for another time.) There is something to be said, however, for poring over the moves of two chess masters to see how it is supposed to be done. One can watch how one side presses the action and how the other side plays to foil this plot. The ideas they come up with as well as how they accurately lay them out on the board can be quite instructive. I’m convinced that playing over thousands of master games helped me progress at least a level or two, as I did not have any formal chess instruction when I was a kid. Here’s what I did. For many years I would play over any and every master game I could get hold of. -

The English School of Chess: a Nation on Display, 1834-1904

Durham E-Theses The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM How to cite: HARRISON, EDWARD,GRAHAM (2018) The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/12703/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Edward Harrison This thesis is submitted for the degree of MA by Research in the department of History at Durham University March 2018 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without the author's prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The English School of Chess: A Nation on Display, 1834-1904 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. -

John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giff to US Chess

Included with this issue: 2021 Annual Buying Guide John D. Rockefeller V Embraces Family Legacy with $3 Million Giftto US Chess DECEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com So you want to improve your chess? NEW! If you want to improve your chess the best place to start is looking how the great champs did it. dŚƌĞĞͲƟŵĞh͘^͘ŚĂŵƉŝŽŶĂŶĚǁĞůůͲ known chess educator Joel Benjamin ŝŶƚƌŽĚƵĐĞƐĂůůtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶƐĂŶĚ shows what is important about their play and what you can learn from them. ĞŶũĂŵŝŶƉƌĞƐĞŶƚƐƚŚĞŵŽƐƚŝŶƐƚƌƵĐƟǀĞ games of each champion. Magic names ƐƵĐŚĂƐĂƉĂďůĂŶĐĂ͕ůĞŬŚŝŶĞ͕dĂů͕<ĂƌƉŽǀ ĂŶĚ<ĂƐƉĂƌŽǀ͕ƚŚĞLJ͛ƌĞĂůůƚŚĞƌĞ͕ƵƉƚŽ ĐƵƌƌĞŶƚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶDĂŐŶƵƐĂƌůƐĞŶ͘ Of course the crystal-clear style of Bobby &ŝƐĐŚĞƌ͕ƚŚĞϭϭƚŚtŽƌůĚŚĂŵƉŝŽŶ͕ŵĂŬĞƐ for a very memorable chapter. ^ƚƵĚLJŝŶŐƚŚŝƐŬǁŝůůƉƌŽǀĞĂŶĞdžƚƌĞŵĞůLJ ƌĞǁĂƌĚŝŶŐĞdžƉĞƌŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂŵďŝƟŽƵƐ LJŽƵŶŐƐƚĞƌƐ͘ůŽƚŽĨƚƌĂŝŶĞƌƐĂŶĚĐŽĂĐŚĞƐ ǁŝůůĮŶĚŝƚǁŽƌƚŚǁŚŝůĞƚŽŝŶĐůƵĚĞƚŚĞŬ in their curriculum. paperback | 256 pages | $22.95 from the publishers of A Magazine Free Ground Shipping On All Books, Software and DVDS at US Chess Sales $25.00 Minimum – Excludes Clearance, Shopworn and Items Otherwise Marked CONTRIBUTORS DECEMBER Dan Lucas (Cover Story) Dan Lucas is the Senior Director of Strategic Communication for US Chess. He served as the Editor for Chess Life from 2006 through 2018, making him one of the longest serving editors in US Chess history. This is his first cover story forChess Life. { EDITORIAL } CHESS LIFE/CLO EDITOR John Hartmann ([email protected]) -

(2012), Adolf Anderssen Vs. Jean Dufresne Berlin

Game # 4 (2012), Adolf Anderssen vs. Jean Dufresne Berlin (1852) (Evans Gambit – this game is known as “The Evergreen Game” ) Chess Club Web Page - utahbirds.org/Chess/ A good thing to learn: Use one “chess trick” to set up another one. (Combination play). Should do: 1. Look along the whole row, file or diagonal that you’re men are on. 2. Attack the same square with several pieces, especially near the King. 3. Be careful when you’re offered something that is “to good to be true.” Some “chess tricks” as they appear in this game: ©M.G.Moody (The first 6 moves of this game are the same as in game #2, two weeks ago; Morache vs. Morphy) 7.O-O d3 Castle - (Getting ready to put the rook on the “King’s file”). Don’t cooperate - (Makes it harder for White to get the “big guys” out). 8. Qb3 Qf6 Attack a weakness (White sets up a “compound” attacking Black’s weak Pawn). Protect - (Black’s Pawn is now protect by two pieces). 9.e5 Qg6 Offer a sacrifice - (White offers a Pawn which could lead to winning a bishop). Don’t cooperate - (Black makes a wise retreat). 10.Re1 Nge7 Get in line with the King - (The Rook is on the same file as the enemy King). Get Knights out - (The Knight protects the King and prepares for castling). 11. Ba3 b5 Attack near the King - (Even if Black castles this is still a good diagonal). Offer a sacrifice - (Black intends to open up a file for the Rook). -

White Knight Review September-October- 2010

Chess Magazine Online E-Magazine Volume 1 • Issue 1 September October 2010 Nobel Prize winners and Chess The Fischer King: The illusive life of Bobby Fischer Pt. 1 Sight Unseen-The Art of Blindfold Chess CHESS- theres an app for that! TAKING IT TO THE STREETS Street Players and Hustlers White Knight Review September-October- 2010 White My Move [email protected] Knight editorial elcome to our inaugural Review WIssue of White Knight Review. This chess magazine Chess E-Magazine was the natural outcome of the vision of 3 brothers. The unique corroboration and the divers talent of the “Wall boys” set in motion the idea of putting together this White Knight Table of Contents contents online publication. The oldest of the three is my brother Bill. He Review EDITORIAL-”My Move” 3 is by far the Chess expert of the group being the Chess E-Magazine author of over 30 chess books, several websites on the internet and a highly respected player in FEATURE-Taking it to the Streets 4 the chess world. His books and articles have spanned the globe and have become a wellspring of knowledge for both beginners and Executive Editor/Writer BOOK REVIEW-Diary of a Chess Queen 7 masters alike. Bill Wall Our younger brother is the entrepreneur [email protected] who’s initial idea of a marketable website and HISTORY-The History of Blindfold Chess 8 promoting resource material for chess players became the beginning focus on this endeavor. His sales and promotion experience is an FEATURE-Chessman- Picking up the pieces 10 integral part to the project. -

Genius Is a Starry Word; but If There Ever Was a Chess

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Paul Morphy 1718 ~ 2018 won the first American Chess Congress 300 in 1857. TRICENTENNIAL “ Genius is a starry word; but if there ever was a chess player to whom that attribute applied, it was Paul Morphy,” according to American chess Grandmaster Andrew Soltis. Morphy was a child chess prodigy who grew up in New Orleans, the son of a Louisi- Paul Morphy took on Louis ana Supreme Court justice who learned chess Paulsen in the first American Chess Congress in 1857. simply by watching the game. At the age of 12, he won two games and had one draw against a famous Hungarian chess player. The next year, Morphy went to Spring Hill College in Mo- bile, Alabama, and then attended Loyola Law School, finishing his law degree when he was One of Paul Morphy’s 20, one year shy of being able to practice law. moves against opponent While he waited to practice law, he became Adolf Anderssen in a series of games played in determined to beat all the great chess players Paris in 1858. Morphy won in the United States and Europe. He won the the series. first American Chess Congress in New York ‘Paul Morphy in 1857 and received a prize from Oliver Wen- - The Chess Champion’ dell Homes. He traveled to England to play illustration Howard Staunton, considered the best player from Ballou’s in Europe. Staunton, however, refused to meet Pictorial, 1859. Morphy. Morphy defeated every other comer Paul Morphy, left, and a friend who would play him, including in a blindfold in a photo that tournament in which he defeated eight op- appeared in the full- length biography ponents in another room. -

Joseph Henry Blackburne

LECTURA DE AJEDREZ I: JOSEPH HENRY BLACKBURNE (10/12/1841–01/09/1924) LA LEYENDA Fue un jugador apodado “La muerte negra”, quien dominó el ajedrez británico durante la última parte del siglo 19. Aprendió a la edad de 18, pero progresó rápidamente y dio cabida a una carrera profesional de ajedrez de más de 50 años. Él llegó a ser el segundo jugador más fuerte del mundo, dio simultáneas y demostraciones a la ciega. Llegó a publicar una colección de sus propios juegos. Comenzó jugando lo que llamamos “tablero” o damas, pero debido a que escuchó hablar sobre Morphy cambió a jugar ajedrez y visitó el Club de Ajedrez de Manchester en 1861. Ahí perdió contra Eduard Pindar, a quien derrotó un año después para proclamarse campeón de la ciudad, incluso delante de Bernhard Horwitz, quien había sido su mentor en la teoría. Incursionó en el ajedrez a la ciega después de que recibiera una derrota en esta modalidad de parte de Louis Paulsen. Tiempo después Joseph jugó contra otros tres jugadores a la ciega, y fue incrementando este número. En 1862 incursionó en el ajedrez profesional derrotando a Wilhelm Steinitz en el Torneo Internacional de Londres, pero quedando noveno en la competición. Sugirió el uso de relojes de ajedrez en las competiciones. Era el jugador más fuerte de Inglaterra en 1870, y de hecho, en el Torneo de Baden-Baden de ese mismo año, quedó en tercer jugar con Gustav Neumann, detrás de Adolfg Anderseen y Wilhelm Steinitz, pero delante de jugadores como Paulsen, De Vere, Winawer, Rosenthal y Von Minckwitz. -

500 King's Gambit Miniatures

il I 500 KING'S GAMBIT miniatufte� Bill Wall THE ECO OPENING KEY C30 1 e4 e5 C31 1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 C32 1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 d3 Nf6 C33 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 C34 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 NC3 C35 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 C36 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 d5 C37 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 C38 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 Bg7 C39 1 e4 e5 2·r4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 SYMBOLS ! good move !! excellent move ? weak move ?? blunder I? interesting move ?! dubious move N.N. no name� unknown player 1. C30/1 DALE BURK - JON WALTHOUR, Dayton, Ohio 1982 1 e4 e5 2 f4 f6? 3 fxe5 fxe5 4 Qh5+ g6 5 Qxe5+ Ne7 6 QxhS 1-0 2. C30/1 REINLE - N.N., Murhau, Germany 1936 1 e4 e5 2 f4 f5? 3 exf5 e4 4 Qh5+ g6 5 fxg6 h6 6 g7 + Ke7 7 Qe5+ Kf7 S gxhS=N! mate 1-0 3. C30/1 NEBERMAN - SILBERMANN, Be rlin 1902 1 e4 e5 2 f4 f5 3 exf5 exf4 4 Qh5+ g6 5 fxg6 Nf6 6 g7 + Nxh5 7 gxhS=Q Qh4+ S Kd1 d6 9 Nf3 Bg4 10 Be2 Qf2? 11 Re1 Nd7 12 Bb5+ KdS 13 QxfS+! NxfS 14 ReS mate 1-0 4. C30/1 H. CHRISTIANSEN - 0. HANSEN, De nmark 1968 1 e4 e5 2 f4 Nc6 3 Bc4 exf4 4 Nc3 Qh4+ 5 Kfl Bc5 6 Nf3?? Q£2 mate 0-1 5.