Remembering Rustin: a Rhetorical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration Mulford Q

Hastings Law Journal Volume 16 | Issue 3 Article 3 1-1965 Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration Mulford Q. Sibley Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mulford Q. Sibley, Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration, 16 Hastings L.J. 351 (1965). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol16/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. Direct Action and the Struggle for Integration By MuLorm Q. Smri.y* A MOST striking aspect of the integration struggle in the United States is the role of non-violent direct action. To an extent unsurpassed in history,1 men's attentions have been directed to techniques which astonish, perturb, and sometimes antagonize those familiar only with the more common and orthodox modes of social conflict. Because non- violent direct action is so often misunderstood, it should be seen against a broad background. The civil rights struggle, to be sure, is central. But we shall examine that struggle in the light of general history and the over-all theory of non-violent resistance. Thus we begin by noting the role of non-violent direct action in human thought and experience. We then turn to its part in the American tradition, par- ticularly in the battle for race equality; examine its theory and illus- trate it in twentieth-century experience; inquire into its legitimacy and efficacy; raise several questions crucial to the problem of civil disobedience, which is one of its expressions; and assess its role in the future battle for equality and integration. -

Dsjfeb08.Pdf

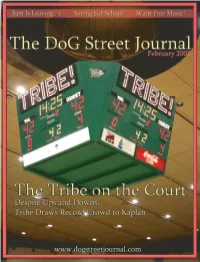

feb. 2008>>>www.dogstreetjournal.com>>>volume 5 issue 6 The DoG Street Journal (what’sinside) (whoweare) Road to Richmond EDITORIALSTAFF Rebecca Hamfeldt >Lobbying the Legislature The DSJ reviews students’ recent trip to Co-Editor in Chief the State legislature to lobby for the Jeri Kent College. Co-Editor in Chief page 5 Stacey Marin Executive Editor In the Know Jonna Knappenberger News Editor >Students and the News Just how informed are students at the Jake Robert Nelson College? The DSJ takes a look at our Interim News Editor generation and the news. Gretchen Hannes page 14 Style Editor John Hill Mrs. President Sports Editor >The White House’s Future Katie Photiadis With presidential primaries in full Opinions Editor swing, one DSJ columnist predicts the Megan Luteran outcome of the 2008 election. Print Photo Editor page 16 Nazrin Roberson Online Photo Editor More than a T-Shirt Ryan Powers >Intramural Sports Online Design Editor Find out what’s behind competing for Michael Duarte the coveted championship t-shirt. Online Design Editor page 18 Keeley Edmonds Business Manager Khaleelah Jones Operations Editor OURMISSION Kellie O’Malley OURMISSION COVERIMAGE Layout Assistant The DSJ is the College’s only For the first time in seasons, Tribe (talktous) monthly newsmagazine and daily men’s basketball is tearing it up The DoG Street Journal online paper. Access us anytime on on the court. There have been The College of William & Mary the web at dogstreetjournal.com. several energy-charged games, Campus Center Basement We strive to provide a quality, including six straight wins and a Office 12B reliable and thought-provoking tough loss against ODU at the media outlet serving the College most well-attended home game (visitus) community with constantly in over a decade. -

Nonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings During Popular Uprisings

Special Report Series Volume No. 2, April 2018 www.nonviolent-conflict.org Nonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings During Popular Uprisings Evan Perkoski and Erica Chenoweth Abstract What drives governments to crack down on and kill their own civilians? And how—and to what extent— has nonviolent resistance historically mitigated the likelihood of mass killings? This special report explores the factors associated with mass killings: when governments intentionally kill 1,000 or more civilian noncombatants. We find that these events are surprisingly common, occurring in just under half of all maximalist popular uprisings against states, yet they are strongly associated with certain types of resistance. Nonviolent uprisings that are free of foreign interference and that manage to gain military defections tend to be the safest. These findings shed1 light on how both dissidents and their foreign allies can work together to reduce the likelihood of violent confrontations. Summary What drives governments to crack down on and kill their own civilians? And how—and to what extent—has nonviolent resistance mitigated the likelihood of mass killings? This special report explores the factors associated with mass killings: when governments intentionally kill 1,000 or more civilian noncombatants. We find that these events are surprisingly common, occurring in just under half of maximalist popular uprisings against the states, yet they are strongly associated with certain types of resistance. Specifically, we find that: • Nonviolent resistance is generally less threatening to the physical well-being of regime elites, lowering the odds of mass killings. This is true even though these campaigns may take place in repressive contexts, demand that political leaders share power or step aside, and are historically quite successful at toppling brutal regimes. -

The Public Eye, Summer 2010

Right-Wing Co-Opts Civil Rights Movement History, p. 3 TheA PUBLICATION OF POLITICAL R PublicEyeESEARCH ASSOCIATES Summer 2010 • Volume XXV, No.2 Basta Dobbs! Last year, a coalition of Latino/a groups suc - cessfully fought to remove anti-immigrant pundit Lou Dobbs from CNN. Political Research Associates Executive DirectorTarso Luís Ramos spoke to Presente.org co-founder Roberto Lovato to find out how they did it. Tarso Luís Ramos: Tell me about your organization, Presente.org. Roberto Lovato: Presente.org, founded in MaY 2009, is the preeminent online Latino adVocacY organiZation. It’s kind of like a MoVeOn.org for Latinos: its goal is to build Latino poWer through online and offline organiZing. Presente started With a campaign to persuade GoVernor EdWard Rendell of PennsYlVania to take a stand against the Verdict in the case of Luis RamíreZ, an undocumented immigrant t t e Who Was killed in Shenandoah, PennsYl - k n u l Vania, and Whose assailants Were acquitted P k c a J bY an all-White jurY. We also ran a campaign / o t o to support the nomination of Sonia h P P SotomaYor to the Supreme Court—We A Students rally at a State Board of Education meeting, Austin, Texas, March 10, 2010 produced an “I Stand With SotomaYor” logo and poster that people could displaY at Work or in their neighborhoods and post on their Facebook pages—and a feW addi - From Schoolhouse to Statehouse tional, smaller campaigns, but reallY the Curriculum from a Christian Nationalist Worldview Basta Dobbs! continues on page 12 By Rachel Tabachnick TheTexas Curriculum IN THIS ISSUE Controversy objectiVe is present—a Christian land goV - 1 Editorial . -

Freedom Budget for All Americans As an Economic Plan

ISSN: 2278-3369 International Journal of Advances in Management and Economics Available online at www.managementjournal.info RESEARCH ARTICLE The Freedom Budget for All Americans as an Economic Plan Enrico Beltramini Notre Dame de Namur University Abstract In the second part of the sixties, A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin envisioned an ambitious economic plan aimed primarily at eradicating poverty and joblessness for all Americans and significantly expanding the boundaries of Johnson’s Great Society. It never gained traction and by the end of the Johnson Presidency was relegated to the margins of historical memory. While the recent literature on the Freedom Budget has argued that the program was politically infeasible, this paper sustains that the Freedom Budget as a plan was economically infeasible. After a summary of the aims and content of the Great Society and the Freedom Budget, this paper determines that a main point of the program’s irrelevance lies to some degree in the implausibility of its economic assumptions and in the denial of any necessary economic trade-off. Keywords: Freedom Budget, Keyserling, Johnson Administration, Great Society, Keynesianism. Introduction The Freedom Budget for All Americans: budget and self-sustainability of the Budgeting Our Resources, 1966-1975, To program, as well as the denial of any Achieve Freedom from Want (also, Freedom necessary economic trade-off, including the Budget or simply Budget), written under the one between inflation and employment. supervision of Bayard Rustin and released First, the article summarizes the main in 1966 by the A. Philip Randolph Institute, features of the Great Society, President was a well developed policy program seeking Johnson’s grandiose vision of universal to secure full economic citizenship for all access to benefits, privileges, income, Americans via an unprecedented housing, hopes, visions, values, government investment. -

A Phenomenological Examination of Self-Identifying LGBTQ Public School Educators

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DigitalCommons@CSP (Concordia University St. Paul) Concordia University St. Paul DigitalCommons@CSP Concordia University Portland Graduate CUP Ed.D. Dissertations Research Spring 6-21-2017 Storied Lives, Unpacked Narratives, and Intersecting Experiences: A Phenomenological Examination of Self-Identifying LGBTQ Public School Educators Robert J. Bizjak Concordia University - Portland, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csp.edu/cup_commons_grad_edd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Bizjak, R. J. (2017). Storied Lives, Unpacked Narratives, and Intersecting Experiences: A Phenomenological Examination of Self-Identifying LGBTQ Public School Educators (Thesis, Concordia University, St. Paul). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.csp.edu/ cup_commons_grad_edd/88 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia University Portland Graduate Research at DigitalCommons@CSP. It has been accepted for inclusion in CUP Ed.D. Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Concordia University - Portland CU Commons Ed.D. Dissertations Graduate Theses & Dissertations Spring 6-21-2017 Storied Lives, Unpacked Narratives, and Intersecting Experiences: A Phenomenological Examination of Self-Identifying LGBTQ Public School Educators Robert J. Bizjak Concordia University - Portland Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.cu-portland.edu/edudissertations Part of the Education Commons CU Commons Citation Bizjak, Robert J., "Storied Lives, Unpacked Narratives, and Intersecting Experiences: A Phenomenological Examination of Self- Identifying LGBTQ Public School Educators" (2017). Ed.D. Dissertations. 39. https://commons.cu-portland.edu/edudissertations/39 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Theses & Dissertations at CU Commons. -

Silent Outsiders: Searching for Queer-Identity in College

SILENT OUTSIDERS: SEARCHING FOR QUEER IDENTITY IN COMPOSITION READERS by TRAVIS W. DUNCAN B.S. Radford University, 2002 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2006 © 2006 Travis W. Duncan ii ABSTRACT This study searches twenty composition readers’ table of contents for the degree of inclusivity of queer people and issues. Four means of erasure are labeled as possible erasing of queer identity: presuming heteronormativity, overt homophobia, perpetuating tokenism, and pathologizing queer identity. The presence of other differences are compared to the number of times that queer identity is referenced in the table of contents. The final portion of the analysis examines the two most inclusive composition readers to understand more clearly how the readers present queer individuals and issues. In a sense, I want to explore the question of how often queer people are discussed or addressed and in what forms within these composition readers. My hope is to develop a means for instructors and students to investigate whether or not, and in what ways a composition reader prescribes presence for the queer individual. iii “Other people have ‘sexuality’ but heterosexual people are ‘just people’”. — Shaun Best This is dedicated to those teachers that strive to make an impact in all students’ lives: students who are straight and those who are queer identified. If not for teachers like those, I would not have the courage to do this type of project. -

Dr. Alveda C. King

Dr. Alveda C. King PASTORAL ASSOCIATE, PRIESTS FOR LIFE DR. ALVEDA C. KING works toward her purpose in life, to glorify God. Dr. King currently serves as a Pastoral Associate and Director of African-American Outreach for Priests for Life and Gospel of Life Ministries. She is also a voice for the Silent No More Awareness Campaign, sharing her testimony of two abortions, God’s forgiveness, and healing. The daughter of the late civil rights activist Rev. A.D. King and his wife Naomi Barber King, Alveda grew up in the civil rights movement led by her uncle, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Her family home in Birmingham, Alabama, was bombed, as was her father’s church office in Louisville, Kentucky. Alveda was jailed during the open housing movement. She sees the pro- life movement as a continuation of the civil rights struggle. Dr. King is a former college professor and served in the Georgia State House of Representatives. She is a best selling author; among her books are How Can the Dream Survive if we Murder the Children? and I Don’t Want Your Man, I Want My Own. She is an accomplished actress and songwriter. The Founder of King for America, Inc., Alveda is also the recipient of a Doctorate of Laws degree from Saint Anselm College. Dr. King lives in Atlanta, where she is the grateful mother of six and a doting grandmother. To arrange a media interview, email [email protected] or call Margaret at 888-735-3448, ext. 251 To invite Alveda King to speak in your area, contact our Speakers Bureau at 888-PFL-3448, ext. -

Alcaraz and Morrison Seek County Posts Photo by Theresa Volpe

PAGE 6 PAGE 8 VOL 33, NO. 22 FEB. 14, 2018 Gaylon Alcaraz. Kevin B. Morrison. Photo by Vern Hester Photo by AJ Kane www.WindyCityMediaGroup.com COOK COUNTY SUE THE T-REX DREAMING Field Museum dinosaur identifies as nonbinary. 1016 Alcaraz and Morrison seek county posts Photo by Theresa Volpe PLAY BALL The play The Wolves looks at a high school girls’ soccer team. Photo of Aurora Real de Asua by Cody Nieset) IN THE ‘HOUSE’ EYE OF THE STORM Author Salman Rushdie talks LGBT Production looks at life of civil-rights issue, book The Golden House. activist Bayard Rustin. PR photo 18 Photo courtesy of Kemati J. Porter 11 14 @windycitytimes1 /windycitymediagroup @windycitytimes www.windycitymediagroup.com 2 Feb. 14,! 2018 WINDY CITY TIMES Tuesday, March 13, 2018 The Clarence Darrow Commemorative Committee invites you to participate in its annual wreath-tossing & symposium commemorating Darrow on the 80th anniversary10 a.m.-noon! of his death! 10 am: Please join us just EAST of the Clarence! Darrow Bridge in Jackson Park (the bridge is under construction) for the traditional tossing of flowers and brief speeches SPECIAL GUEST SPEAKER at the DARROW BRIDGE: Marisa Novara, Metropolitan Planning Council. 10:45 am: Symposium begins in the Museum! of Science and Industry: Rosenwald Room Featured Symposium Topics: 80 Years Since Darrow’s! Death and ! Celebrating! 50 Years of the Fair Housing Law Nabeela! Rasheed is a Pakistani, British, American, Muslim, Queer, Lawyer, Biochemist, activist. She moved to the U.S.! and worked for a law degree. Dr. Rasheed retrained as a lawyer in Chicago. -

Start Debating Stop Hating

The surest sign one is losing a debate is to resort to character with the Tea Party movement. Some on the Left have even impugned the assassination. The Southern Poverty Law Center, a liberal fundraising Manhattan Declaration - which upholds the sanctity of life, the value of machine whose tactics have been condemned by observers across the traditional marriage and the fundamental right of religious freedom - as an political spectrum, is doing just that. anti-gay document and have forced its removal from general communications networks. The group, which was once known for combating racial bigotry, is now attacking several groups that uphold Judeo-Christian moral views, including This is intolerance pure and simple. Elements of the radical Left are trying marriage as the union of a man and a woman. to shut down informed discussion of policy issues that are being considered by Congress, legislatures, and the courts. How does the SPLC attack? By labeling its opponents “hate groups.” No discussion. No consideration of the issues. No engagement. No debate! Tell the radical Left it is time to stop spreading hateful rhetoric attacking individuals and organizations merely for expressing ideas with which they These types of slanderous tactics have been used against voters who signed disagree. Our debates can and must remain civil - but they must never be petitions and voted for marriage amendments in all thirty states that have suppressed through personal assaults that aim only to malign an opponent’s considered them, as well as against the millions of Americans who identify character. START DEBATING STOP HATING You can take action by adding your name to the following statement: We, the undersigned, stand in solidarity with Family Research Council, American Family Association, Concerned Women of America, National Organization for Marriage, Liberty Counsel and other pro-family organizations that are working to protect and promote natural marriage and family. -

Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit?

The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Hornstein Jewish Professional Leadership Program Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner Ph.D., Advisors In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Leah Robbins May 2020 Copyright by Leah Robbins 2020 Acknowledgements This thesis was made possible by the generous and thoughtful guidance of my two advisors, Professors Ellen Smith and Jonathan Krasner. Their content expertise, ongoing encouragement, and loving pushback were invaluable to the work. This research topic is complex for the Jewish community and often wrought with pain. My advisors never once questioned my intentions, my integrity as a researcher, or my clear and undeniable commitment to the Jewish people of the past, present, and future. I do not take for granted this gift of trust, which bolstered the work I’m so proud to share. I am also grateful to the entire Hornstein community for making room for me to show up in my fullness, and for saying “yes” to authentically wrestle with my ideas along the way. It’s been a great privilege to stretch and grow alongside you, and I look forward to continuing to shape one another in the years to come. iii ABSTRACT The “Black-Jewish Coalition” Unraveled: Where Does Israel Fit? A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Leah Robbins Fascination with the famed “Black-Jewish coalition” in the United States, whether real or imaginary, is hardly a new phenomenon of academic interest. -

Anniversary of the Thalhimers Lunch Counter Sit-In

TH IN RECOGNITION OF THE 50 ANNIVERSARY OF THE THALHIMERS LUNCH COUNTER SIT-IN Photo courtesy of Richmond Times Dispatch A STUDY GUIDE FOR THE CLASSROOM GRADES 7 – 12 © 2010 CenterStage Foundation Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Standards of Learning 4 Historical Background 6 The Richmond 34 10 Thalhimers Sit-Ins: A Business Owner’s Experience 11 A Word a Day 15 Can Words Convey 19 Bigger Than a Hamburger 21 The Civil Rights Movement (Classroom Clips) 24 Sign of the Times 29 Questioning the Constitution (Classroom Clips) 32 JFKs Civil Rights Address 34 Civil Rights Match Up (vocabulary - grades 7-9) 39 Civil Rights Match Up (vocabulary - grades 10-12) 41 Henry Climbs a Mountain 42 Thoreau on Civil Disobedience 45 I'm Fine Doing Time 61 Hiding Behind the Mask 64 Mural of Emotions 67 Mural of Emotions – Part II: Biographical Sketch 69 A Moment Frozen in Our Minds 71 We Can Change and Overcome 74 In My Own Words 76 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Contributing Authors Dr. Donna Williamson Kim Wasosky Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt Janet Krogman Jon King The lessons in this guide are designed for use in grades 7 – 12, and while some lessons denote specific grades, many of the lessons are designed to be easily adapted to any grade level. All websites have been checked for accuracy and appropriateness for the classroom, however it is strongly recommended that teachers check all websites before posting or otherwise referencing in the classroom. Images were provided through the generous assistance and support of the Valentine Richmond History Center and the Virginia Historical Society.