Musicfirst Petition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Career-Clintdantinne.Pub

Director of Event Services President COLONEL C PRODUCTIONS DANCE RADIO NETWORK LLC Orlando, Florida Area Mid-Atlantic Region Oct 2015—present Jun 2010—May 2012 President and Executive Creative Director of Communications and Director Media Technology GO FAR PR LLC BRANDYWINE SCHOOL DISTRICT Greater Philadelphia Area Wilmington, Delaware Greater New York Area Jan 1993—Jun 2010 Jun 2012—Oct 2015 WIDENER UNIVERSITY AMERICAN SCHOOL OF HYPNOSIS GRADUATED: Bachelor of Arts degree in Diploma of Hypnotism Media Studies, minor in Psychology Hypnotherapy/Hypnotherapist Chester, Pennsylvania Newark, Delaware MAINE MEDIA WORKSHOPS + COLLEGE FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY Certificate in Film Director's Craft Certificate in Hospitality and Tourism Film/Video and Photographic Arts Management Rockport, Maine Boca Raton, Florida (Online) https://clintdantinne.com/about | [email protected] | (407) 401-2659 Director of Event Services • Event & Team Coordinator (Producer & Director) - Marketing & Media Specialist; Voiceover talent and radio syndicator - Public Speaker, Photographer, UAV (Drone) Pilot, Audio & Video Producer, Multimedia Editor, Venue Lighting Technician, Disc Jockey, Photo Booth Attendant President and Executive Creative Director • Marketing and Promotions Agency Director (Publicity, Social Media & Event Specialist) - The agency was driven from the need to promote content and events efficiently toward a viable source for publicity by energizing the resources of various media, trade shows, and testimonials Founder and President • President -

FM Subcarrier Corridor Assessment for the Intelligent Transportation System

NTIA Report 97-335 FM Subcarrier Corridor Assessment for the Intelligent Transportation System Robert O. DeBolt Nicholas DeMinco U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Mickey Kantor, Secretary Larry Irving, Assistant Secretary for Communications and Information January 1997 PREFACE The propagation studies and analysis described in this report were sponsored by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), U.S. Department of Transportation, McLean, Virginia. The guidance and advice provided by J. Arnold of FHWA are gratefully acknowledged. iii CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background.......................................................................................................................1 1.2 Objective...........................................................................................................................2 1.3 Study Tasks.......................................................................................................................3 1.4 Study Approach................................................................................................................3 1.5 FM Subcarrier Systems.....................................................................................................4 2. ANALYSIS OF CORRIDOR 1 - Interstate 95 from Richmond, Virginia, to Portland, Maine......................................................................................................................5 3. -

2009 Hall of Fame Induction May 5, 2009 Bill Chambless

2009 Hall of Fame induction May 5, 2009 Bill Chambless Bill was the host of the popular ‘Scratchy Grooves’ program on WXDR and WVUD from 1984-2002. Initially meant to be a 6 week temporary program that featured old recordings from Bill’s collection (“scratches and all!”), Scratchy Grooves continued on, and in perhaps the greatest testament to its creator, lasted well past Bill’s death in 2003. Additionally, old shows culled from Bill’s son’s tribute website were brought back to the airwaves in 2009. Bill Chambless Bill combined a vast knowledge of his musical subject matter with a warm, inviting voice, and a quirky sense of humor to become a beloved figure for many WXDR/WVUD listeners. His ability to share the joy of radio and music with his listeners was unparalleled. WVUD hosts and listeners alike receive a healthy dose of Bill’s voice every day, oftentimes without even being aware of it. Dozens of station promos that Bill created have withstood the test of time and are still being happily played and listened to by people who were not around when Bill initially worked at the radio station. Greer Firestone Every story has a beginning and when it was decided that the University of Delaware needed a radio station, student Greer Firestone was among those who made it happen. On a cold night in October 1968 at around 8 PM, the ten-watt carrier current WHEN-AM began broadcasting with the prophetic words “WHEN is Now!” spoken by the station’s co-founder and General Manager, Greer Firestone. -

Cooperative Program Tape Networks in Noncommercial EDRS

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 115 254 IR 002 798 AUTHOR Nordgren, Peter D. TITLE Cooperative Program Tape Networks in Noncommercial Radio. PUB DATE Dec 75 NOTE 94p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$4.43 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Cooperative Programs; *Educational Radio; Higher Education; *Programing (Broadcast); *Questionnaires; Shared Services; Statistical Data; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS Cooperative Program Tape Networks ABSTRACT Over 200 noncommercial radio stations responded to a survey to gather data on the characteristics of member stations and to sample the opinion of nonmembers toward a cooperative network concept. A second survey of 18 networks sought to gather indepth information on network operation. Results showed that 22.2 percent of the stations surveyed were participating in program cooperatives, and over 79 percent felt that network participation would be beneficial. It was concluded that the cooperative program tape network should continue in order to fulfill specialized programing needs. A copy of the two questionnaires, the letter of transmittal, and the mailing list is appended. A list of the networks that participated in the study, 12 statistical tables, and a 20-item bibliography are included. (Author/DS) lb *********************************************************************** * Documents acquired by ERIC include many informal unpublished * * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makes every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. Nevertheless, items of marginal * * reproducibility are often encountered and this affects the quality * *of the microfiche and hardcopy reproductions ERIC makes available * *via the ERIC Document ReproductionService (EDRS). EDRS is not * *responsible for the quality of theoriginal document. Reproductions* *supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made from the original. -

Petition for Rulemaking

REC Networks NCE Outside Urbanized Areas Petition for Rulemaking Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC In the matter of: ) ) MB Docket No. _________ Amendment of Part 73 of the Commission’s ) Rules to Introduce New Local Noncommercial ) RM-_______________ Educational Broadcast Stations Outside of Major ) Markets and Urbanized Areas ) PETITION FOR RULEMAKING OR IN THE ALTERNATE, PETITION FOR DECLARATORY RULING TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph I. INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 1 II. NCE POLICY HAS BEEN HISTORICALLY ABOUT “BIG AND WIDE” AS OPPOSED TO “RIGHTSIZED AND LOCAL” A. What is is a community?............................................................................... 4 B. The Willards example................................................................................... 7 C. Local communities are shut out..................................................................... 8 III. THE TECHNICAL MYTHS OF SECOND AND THIRD ADJACENT OVERLAP BY SMALLER FACILITIES HAVE ALREADY BEEN DEBUNKED A. The Raleigh waiver standard........................................................................ 9 B. LPFM’s first iteration of second-adjacent waivers....................................... 11 C. The MITRE Study for LPFM third-adjacent channels................................. 12 D. The Living Way method................................................................................ 13 E. The different definitions of “interference” -

USA National

USA National Hartselle Enquirer Alabama Independent, The Newspapers Alexander Islander, The City Outlook Andalusia Star Jacksonville News News Anniston Star Lamar Leader Birmingham News Latino News Birmingham Post-Herald Ledger, The Cullman Times, The Daily Marion Times-Standard Home, The Midsouth Newspapers Daily Mountain Eagle Millbrook News Monroe Decatur Daily Dothan Journal, The Montgomery Eagle Enterprise Ledger, Independent Moundville The Florence Times Daily Times Gadsden Times National Inner City, The Huntsville Times North Jefferson News One Mobile Register Voice Montgomery Advertiser Onlooker, The News Courier, The Opelika- Opp News, The Auburn News Scottsboro Over the Mountain Journal Daily Sentinel Selma Times- Pelican, The Journal Times Daily, The Pickens County Herald Troy Messenger Q S T Publications Tuscaloosa News Red Bay News Valley Times-News, The Samson Ledger Weeklies Abbeville Sand Mountain Reporter, The Herald Advertiser Gleam, South Alabamian, The Southern The Atmore Advance Star, The Auburn Plainsman Speakin' Out News St. Baldwin Times, The Clair News-Aegis St. Clair BirminghamWeekly Times Tallassee Tribune, Blount Countian, The The Boone Newspapers Inc. The Bulletin Centreville Press Cherokee The Randolph Leader County Herald Choctaw Thomasville Times Tri Advocate, The City Ledger Tuskegee Clanton Advertiser News, The Union Clarke County Democrat Springs Herald Cleburne News Vernon Lamar Democrat Conecuh Countian, The Washington County News Corner News Weekly Post, The County Reaper West Alabama Gazette Courier -

June 20-30, 2019

■ INAUGURAL SEASON■ JUNE 20-30, 2019 8 scintillating performances KATE RANSOM AUGUSTINE MERCANTE artistic director 19 accomplished artists festival manager ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Acknowledging, with gratitude, the following supporters of Serafin Summer Music 2019: SPONSORS The Music School of Delaware Administrative Staff The Music School of Delaware Board of Directors University of Delaware Department of Music William J. Stegeman, Ph.D. Jacobs Music Company Harry’s Savoy Grill Tonic Bar and Grille Montrachet Fine Foods and Centreville Cafe Delaware Today GateHouse Media Delaware WDEL MEDIA SUPPORT ARTISTS’ HOUSING HOSTS WRTI Karen Jessee WHYY Betty and Don Duncan WILM Nancy and David Saunders WDDE Marie and Ed Stewart WMPH Richard Hess InWilmington Lisa and John Mulrooney Justin Bartels and Gus Mercante PROGRAM NOTES Michael Redmond RECEPTIONS AND STEWARDSHIP Troy Nuss GRAPHIC DESIGN Bradford Rush Jennifer Marang COCA Gallery FESTIVAL MANAGER PUBLICITY AND PROMOTION Gus Mercante Tara Hurlebaus, Linkbridge Communications Michelle Kramer-Fitzgerald, Arts in Media STAGE MANAGER/CREW Yung-Chen Lin, concert manager Dustin Manucci Amanda Stejskal THANK YOU! 2 FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Friends, Stegeman, as well as lead business sponsor, Jacobs Music Company, means that the first two seasons Excitement has resonated throughout the year of the festival are sure-footed. This allows time to of planning and preparations for the inaugural secure other support from friends who wish to help year of Serafin Summer Music. What a pleasure keep the experience thriving in the years ahead. and privilege it is to bring to our audiences eight concerts, festival-syle, over two weeks this month! Our generous sponsors are recognized throughout the program booklet. -

State of the Media: Audio Today a Focus on Public Radio December 2014

STATE OF THE MEDIA: AUDIO TODAY A FOCUS ON PUBLIC RADIO DECEMBER 2014 STATE OF THE MEDIA: AUDIO TODAY Q4 Copyright © 2014 The Nielsen Company 1 THE ECLECTIC AUDIO LANDSCAPE In today’s fragmented media world, where consumers have more choices and more access to content than ever before, audio remains strong. 91.3% of all Americans (age 12+) are using radio during the week. Since the beginning of 2010, the national weekly radio audience has grown from 239.7 million to 243 million listeners tuning in across more than 250 local markets in every corner of the country. 243 MILLION AMERICANS LISTEN TO RADIO EACH WEEK In a time of changing habits and new digital platforms, radio’s consistent audience numbers are quite remarkable. With the holidays just around the corner, consumers will be turning to the radio to catch their favorite sounds of the season or stay in touch with what’s happening in their local community each day. PUBLIC RADIO OFFERS AN UNCOMMON MIX OF PROGRAMMING FOR 32 MILLION LISTENERS This year we have profiled the overall radio landscape, multicultural audiences and network radio listeners, and for our final report we turn our attention to Public Radio; the more than 900 rated stations which offer an eclectic mix of news, entertainment, music and cultural programming in markets large and small. Public Radio is a unique and relevant part of the lives of 32 million Americans and exists in large part due to the financial support of the listeners we examine in the following pages. Source: RADAR 123, December 2014; M-SU MID-MID, Total -

FM-1949-07.Pdf

MM partl DIRECTORY BY OPL, SYSTEMS COUNTY U POLICE 1S1pP,TE FIRE FORESTRYOpSp `p` O COMPANIES TO REVISED LISTINGS 1, 1949 4/ka feeZ means IessJnterference ... AT HEADQUARTERS THE NEW RCA STATION RECEIVER Type CR -9A (152 -174 Mc) ON THE ROAD THE NEW RCA CARFONE Mobile 2 -way FM radio, 152 -174 Mc ...you get the greatest selectivity with RCA's All -New Communication Equipment You're going to hear a lot about selectivity from potentially useful channels for mobile radio communi- now on. In communication systems, receiver selectiv- cation systems. ity, more than any other single factor, determines the For degree of freedom from interference. complete details on the new RCA Station Re- This is impor- ceiver type CR -9A, tant both for today and for the future. and the new RCA CARFONE for mobile use, write today. RCA engineers are at your Recognizing this fact, RCA has taken the necessary service for consultation on prob- steps to make its all -new communication equipment lems of coverage, usage, or com- the most selective of any on the market today. To the plex systems installations. Write user, this means reliable operation substantially free Dept. 38 C. from interference. In addition, this greater selectivity Free literature on RCA's All -New now rhakes adjacent -channel operation a practical Communication Equipment -yours possibility - thereby greatly increasing the number of for the asking. COMMUN /CAT/ON SECT/ON RADIO CORPORATION of AMERICA ENGINEERING PRODUCTS DEPARTMENT, CAMDEN, N.J. In Canada: R C A VICTOR Company limited, Montreal Á#ofher s with 8(11(011' DlNews ERIE'S FIRST TV STATION Says EDWARD LAMB, publisher of "The Erie Dis- telecasting economics. -

Test Booklet

Test Booklet Subject: LA, Grade: 07 Grade 7 Reading 2009 Student name: Author: Delaware District: Delaware Released Tests Printed: Friday June 24, 2011 Grade 7 Reading 2009 LA:07 The Business of Radio by Denise Parks You are traveling in the car on the way to your friend’s house when your brother reaches towards the car radio controls. “No!” you cry. At the push of a button you are transported from the music you love to your brother’s talk radio show. Your mother reaches over and presses another button. Now it’s all about the weather. As frustrated as you may feel, it is actually pretty amazing that there are so many options at your finger tips. Did you ever stop to consider how radio stations work? Or how radio stations choose the songs that they play? Much planning and preparation goes into getting a radio station and its programming on the air. A LICENSE TO PLAY Did you know that as a United States citizen, you actually own part of all the radio stations that you hear? Here’s how it works. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) provides licenses that assign parts of the radio dial to companies that run each radio station. In return, the company agrees to provide programming that is interesting and important to its listeners. However, if listeners complain that a station is not living up to the agreement, then the radio station risks being removed from the air. For example, a station that promises to play only “clean” music but plays a song with profanity puts itself at risk at having its license revoked by the FCC. -

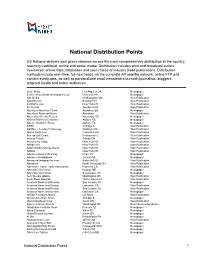

National Distribution Points

National Distribution Points US National delivers your press releases across the most comprehensive distribution in the country, reaching traditional, online and social media. Distribution includes print and broadcast outlets, newswires, online sites, databases and your choice of industry trade publications. Distribution methods include real−time, full−text feeds via the complete AP satellite network, online FTP and content syndicates, as well as personalized email newsletters to reach journalists, bloggers, targeted media and online audiences. 20 de'Mayo Los Angeles CA Newspaper 21st Century Media Newspapers LLC New York NY Newspaper 3BL Media Northampton MA Web Publication 3pointD.com Brooklyn NY Web Publication 401KWire.com New York NY Web Publication 4G Trends Westboro MA Web Publication Aberdeen American News Aberdeen SD Newspaper Aberdeen Business News Aberdeen Web Publication Abernathy Weekly Review Abernathy TX Newspaper Abilene Reflector Chronicle Abilene KS Newspaper Abilene Reporter−News Abilene TX Newspaper ABRN Chicago IL Web Publication ABSNet − Lewtan Technology Waltham MA Web Publication Absolutearts.com Columbus OH Web Publication Access Gulf Coast Pensacola FL Web Publication Access Toledo Toledo OH Web Publication Accounting Today New York NY Web Publication AdAge.com New York NY Web Publication Adam Smith's Money Game New York NY Web Publication Adotas New York NY Web Publication Advance News Publishing Pharr TX Newspaper Advance Newspapers Jenison MI Newspaper Advanced Imaging Pro.com Beltsville MD Web Publication -

Delaware Emergency Alert System Plan

Delaware Emergency Alert System Plan 2020 Prepared by the Delaware State Emergency Communications Committee As prepared at the October 18, 2019 Annual Meeting. 2020 DE State EAS Plan submitted for FCC Approval on 01/31/2020 Delaware Emergency Alert System Plan 2020 Page 2 As submitted for FCC Approval Delaware Emergency Alert System Plan 2020 Page 3 CONTENTS 2020 EAS Plan Overview pg 4 SECC Committee Members pg 4 SECC Governance Requirements of the FCC pg 5 Alert Origination pg 6 Designated Authorities for EAS Activations pg 6 Delaware EAS Event Codes with Recommendations of SECC pg 7-8 Delaware EAS Operational Areas pg 9 Monitoring Assignments – Table 1 0f 3 (Formerly LP Matrix) pg 10 Monitoring Assignments – Tables 2 of 3 – Participating Nationals By Operational Area (Alphabetically) – pg 11-14 Table 2a – Kent County pg 11 Table 2b – New Castle County pg 12 Table 2c – Sussex County pg 13-14 Monitoring Assignments – Table 3 of 3 – Exceptions to the Monitoring Assignments pg 15 Monitoring Assignments – Alphabetical Listing pg 16-18 Alerting Procedures – Rules for EAS Activation pg 19-24 Monitoring NWS Alerts and NOAA Weather Radio (NWR) Locations pg 20 EMnet Emergency Messaging Network pg 20 Amber Alert Plan Rules pg 21-23 Code Blue Alert Rules pg 24 Alerting Procedures – EAS Testing Rules pg 25 Reporting and Resolving EAS Issues pg 25 Handling Errors with EAS and Remembering to Report False EAS Alerts pg 26 Common Alerting Protocol (CAP)/IPAWS pg 27 Commercial Mobile Alert System (CMAS) and Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) pg 27 Multilingual Alerting Information pg 28 Local Area Plans pg 29 Signatures pg 30 As submitted for FCC Approval Delaware Emergency Alert System Plan 2020 Page 4 OVERVIEW The Emergency Alert System (EAS) provides the President with the capability to relay immediate communications and information to the general public at the national, state, and local area levels during periods of national emergency.