Free Ports, Offshore Capitalism, and Art Capital

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interview with Yves Bouvier

arts Editorial y Interview with Yves Bouvier John Zarobell Department of International Studies, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94117, USA; [email protected] Responses translated from the French by John Zarobell with support from Samuel Weeks. Thanks are due to y Alexandra Dubourg for her invaluable assistance and to Johanna Grawunder. Received: 19 August 2020; Accepted: 13 September 2020; Published: 21 September 2020 1. Introduction Yves Charles Edgar Bouvier is a founder and/or shareholder of the following firms: Expositions Natural le Coultre SA (Geneva), Fine Art Transports Natural le Coultre SA (Geneva), Le Freeport Management Pte Ltd (Singapore), The Singapore Freeport Real Estate Pte Ltd, The Luxembourg Freeport Management Company SA, The Luxembourg Freeport Real Estate SA, and Art Culture Studio SA (Geneva). He is a recipient of the Order of Merit from the Ministry of Culture of the Federation of Russia and serves as Governor of the Board of the National Cultural Heritage of Russia, and has previously served as a Board Member of ARIF (2000–2003), a self-regulatory organization approved by the financial market supervision authority (FINMA) to enforce anti-money laundering legislation. John Zarobell, Associate Professor of International Studies at the University of San Francisco, author of Art and the Global Economy. Knowing that this Special Issue of Arts on the Contemporary Art Market would include a series of articles on freeports, I requested an interview with Yves Bouvier, the man who has been central to the development of this business model, and an art dealer for more than thirty years. While I had originally hoped to visit Luxembourg and to speak with M. -

Freeports and the Hidden Value of Art

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center International Studies Faculty Publications International Studies 11-12-2020 Freeports and the Hidden Value of Art John Zarobell Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/international_fac Part of the International and Area Studies Commons arts Article Freeports and the Hidden Value of Art John Zarobell Department of International Studies, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94117, USA; [email protected] Received: 25 August 2020; Accepted: 12 November 2020; Published: 18 November 2020 Abstract: At first glance, the global art trade—currently valued around $60 billion—is a miniscule piece of global economic production. But due to the unregulated nature of the art market, it serves a key function within the larger network of the accumulation and distribution of capital worldwide. This deregulated market intersects with the offshore domain in freeports, an archipelago of tax-free storage facilities that stretch from Singapore to Geneva to Delaware. The burgeoning of freeports globally suggests that speculation has become a more prominent pattern of art investment, but it also demonstrates that tax avoidance is a goal of such speculators and the result is that more art works are being taken out of circulation and deposited in vaults beyond the view of regulatory authorities. Despite its size, the art trade can demonstrate broader trends in international finance and, by examining offshore art storage that occurs in freeports, it will be possible to locate some of the hidden mechanisms that allow the global art market to flourish on the margins of the economy as well as to perceive a shift in which the economic value of art works predominates over their cultural value. -

Art & Finance Report 2019

Art & Finance Report 2019 6th edition Se me Movió el Piso © Lina Sinisterra (2014) Collect on your Collection YOUR PARTNER IN ART FINANCING westendartbank.com RZ_WAB_Deloitte_print.indd 1 23.07.19 12:26 Power on your peace of mind D.KYC — Operational compliance delivered in managed services to the art and finance industry D.KYC (Deloitte Know Your Customer) is an integrated managed service that combines numerous KYC/AML/CTF* services, expertise, and workflow management. The service is supported by a multi-channel web-based platform and allows you to delegate the execution of predefined KYC/AML/CTF activities to Deloitte (Deloitte Solutions SàRL PSF, ISO27001 certified). www2.deloitte.com/lu/dkyc * KYC: Know Your Customer - AML/CTF: Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Empower your art activities Deloitte’s services within the Art & Finance ecosystem Deloitte Art & Finance assists financial institutions, art businesses, collectors and cultural stakeholders with their art-related activities. The Deloitte Art & Finance team has a passion for art and brings expertise in consulting, tax, audit and business intelligence to the global art market. www.deloitte-artandfinance.com © 2019 Deloitte Tax & Consulting dlawmember of the Deloitte Legal network The Art of Law DLaw – a law firm for the Art and Finance Industry At DLaw, a dedicated team of lawyers supports art collectors, dealers, auctioneers, museums, private banks and art investment funds at each stage of their project. www.dlaw.lu © 2019 dlaw Art & Finance Report 2019 | Table of contents Table of contents Foreword 14 Introduction 16 Methodology and limitations 17 External contributions 18 Deloitte CIS 21 Key report findings 2019 27 Priorities 31 The big picture: Art & Finance is an emerging industry 36 The role of Art & Finance within the cultural and creative sectors 40 Section 1. -

Art & Finance Report 2017

Art & Finance Report 2017 5th edition REFUGEE ASTRONAUT II © YINKA SHONIBARE MBE (2016), PHOTOGRAPHER: STEPHEN WHITE Empower your lifestyle Protect your passions We believe the best client relationships are all about partnerships. AXA ART not only helps clients to protect their assets but also provides detailed bespoke guidance on all aspects of managing a collection, including loss prevention, mitigation and conservation. As pioneers of lifestyle protection insurance, we work closely with policyholders, insurance advisers and a whole network of art experts to provide a seamless service, combining in-depth advice on risk management with a first-class claims process. www.AXA-ART.com Ad_Deloitte_3.indd 1 31.07.17 11:46 Empower your lifestyle Protect your passions We believe the best client relationships are all about partnerships. AXA ART not only helps clients to protect their assets but also provides detailed bespoke guidance on all aspects of managing a collection, including loss prevention, mitigation and conservation. As pioneers of lifestyle protection insurance, we work closely with policyholders, insurance advisers and a whole network of art experts to provide a seamless service, combining in-depth advice on risk management with a first-class claims process. www.AXA-ART.com Ad_Deloitte_3.indd 1 31.07.17 11:46 François PRIVAT ART EXPERT NOT JUST ANOTHER FREEPORT LE FREEPORT | LUXEMBOURG Service - Transparency - Security Ultra-safe and secure facility dedicated to storing, handling, and trading art and other valuables with direct access to tarmac. www.lefreeport.com INVESTMENT HOUSE PRIVATE BANKING ASSET MANAGEMENT THE REAL VALUE OF MONEY IS WHAT YOU CREATE WITH IT. -

A Freeport Comes to Luxembourg, Or, Why Those Wishing to Hide Assets Purchase Fine Art

arts Article A Freeport Comes to Luxembourg, or, Why Those Wishing to Hide Assets Purchase Fine Art Samuel Weeks College of Humanities and Sciences, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19144, USA; samuel.weeks@jefferson.edu Received: 4 June 2020; Accepted: 4 August 2020; Published: 9 August 2020 Abstract: This article addresses how global art markets are becoming an outlet of choice for those wishing to hide assets. Recent efforts by the OECD and the U.S. Treasury have made it more difficult for people to avoid taxes by taking money “offshore”. These efforts, however, do not cover physical assets such as fine art. Citing data collected in Luxembourg—a jurisdiction angling to become a worldwide leader in “art finance”—I discuss the characteristics of this emerging system of opaque economic activity. The first of these is a “freeport”, a luxurious and securitized warehouse where investors can store, buy, and sell art tax free with minimal oversight. The second element points to the work of art-finance professionals, who issue loans using fine art as collateral and develop “art funds” linked to the market value of certain artworks. The final elements cover lax scrutiny by enforcement authorities as well as the secrecy techniques typically on offer in offshore centers. Combining these elements in jurisdictions such as Luxembourg can make mobile and secret the vast wealth stored in fine art. I end the article by asking whether artworks linked to freeports and opaque financial products have become the contemporary version of the numbered Swiss bank account or the suitcase full of cash. -

European Commission President Jean- Claude Juncker Must Close Tax

AiA Art News-service European Commission president Jean- Claude Juncker must close tax loopholes at Luxembourg freeport, MEP says German politician Wolf Klinz describes the art storage facility as “high risk” for money laundering and tax evasion ANNY SHAW 31st January 2019 12:11 GMT Jean-Claude Juncker speaking at the Munich Security Conference in 2018 © MSC/Kuhlmann Members of the European Parliament are stepping up their fight against alleged money laundering and tax evasion through the use of freeports—high-security warehouses which hold art and other valuable assets, such as cars, wine and jewellery, tax free. In a letter dated 8 January, the German MEP Wolf Klinz called on Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, to close loopholes that potentially allow for financial crimes to be committed. Referring specifically to Le Freeport Luxembourg, which opened its steel turnstiles to VIP bankers, art dealers and collectors in August 2014, Klinz says the storage facility had “been alleged to be a fertile ground for money laundering and tax evasion”. He described Le Freeport, which is located minutes away from Findel airport and houses eight showrooms, a restoration workshop and a garage for collectable cars, as a “blind spot” in Juncker’s efforts to boost financial transparency in the EU. The complex was built while Juncker was Luxembourg’s prime minister and enables clients to fly in their objects and trade them inside the freeport’s walls without incurring customs or sales tax. Juncker replied to Klinz’s letter by telling him he had passed on the German MEP’s concerns to Pierre Moscovici, the European commissioner for economic and financial affairs. -

The Emergence of New Corporations Free Zones and the Swiss Value Storage Houses

10 The Emergence of New Corporations Free Zones and the Swiss Value Storage Houses Oddný Helgadóttir 10.1 Introduction This chapter introduces the concept of a ‘Luxury Freeport’, positioning such tax- and duty-free storage sites as new players in the ever-evolving ecosystem of the offshore world. To date, Luxury Freeports have largely passed under the radar of academic research and they represent an important lacuna in the academic scholarship on offshore activity. In his state of the art on offshores, The Hidden Wealth of Nations, economist Gabriel Zucman makes this point explicitly, noting that most current estimates of offshore wealth do not extend to non-financial wealth kept in tax havens: This includes yachts registered in the Cayman Islands, as well as works of art, jewelry, and gold stashed in freeports—warehouses that serve as repositories for valuables. Geneva, Luxembourg, and Singapore all have one: in these places, great paintings can be kept and traded tax-free—no customs duty or value-added tax is owed—and anonymously, without ever seeing the light of day. (2015, pp. 44–5) There are no reliable estimates of the value of goods stored in Luxury Freeports.¹ A recent New York Times article reports that art dealers and insurers believe that the works of art contained in the Geneva Freeport, a pioneer in the Luxury Freeport business, would be enough ‘to create one of the world’s great museums’. Similarly, a London-based insurer concludes that there isn’t ‘a piece of paper wide enough to write down all the zeros’ needed to capture the value of wealth stored in Geneva (Segal 2012). -

Jean-Claude Juncker Dismisses Claims That Freeports Are

AiA Art News-service Jean-Claude Juncker dismisses claims that freeports are ‘systematically used to commit fraud’ European Commission president rebuffs German MEP Wolf Klinz's demand for a proper investigation into the management of Le Freeport Luxembourg ANNY SHAW 12th March 2019 11:45 GMT Le Freeport Luxembourg © Luca Fascini 2014 The European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker has rejected allegations of fraud and irregularities related to the management of Le Freeport Luxembourg, which is owned by the Swiss art dealer Yves Bouvier. In a letter dated 8 January, the German MEP Wolf Klinz called on Junckerto close loopholes that potentially allow for financial crimes to be committed at freeports after concerns were raised by the EU’s Tax3 committee. Referring specifically to Le Freeport Luxembourg, which opened its steel turnstiles to VIP bankers, art dealers and collectors in August 2014, Klinz says the storage facility had “been alleged to be a fertile ground for money laundering and tax evasion”. The complex was built while Juncker was Luxembourg’s prime minister and enables clients to fly in high-value possessions such as cars, jewellery and art and trade them inside the freeport’s walls without incurring customs or sales tax. Freeports are increasingly being used as facilities to permanently park assets. However, in a letter dated 28 February, Pierre Moscovici, the European commissioner for economic and financial affairs, responded on behalf of Juncker saying that “there was no evidence showing that free zones in the EU are systematically used to commit fraud”. Rather, freeports are “useful to simplify commercial operations”. -

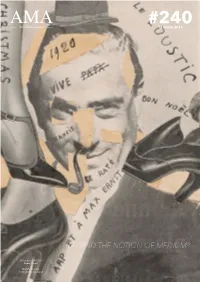

Beyond the Notion of Medium?

#240 18 march 2016 BEYOND THE NOTION OF MEDIUM? Tableau Rastadada (1920) Francis Picabia MoMA, New York © 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich #240 • 18 MARCH 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS P. 5 P.11 BEYOND THE NOTION OF MEDIUM? TOP STORIES P.14 P.16 P.20 MUSEUMS CARINE FOL GALLERIES P.21 P.26 P.27 GALERIE DES DATA MODERNES ARTISTS NIELE TORONI P.33 P.34 AUCTION FAIRS AND FESTIVALS 2 This document is for the exclusive use of Art Media Agency’s clients. Do not distribute. Subscribe for free. 10TH ANNIVERSARY THE FIRST INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON CONTEMPORARY DRAWING IN FRANCE CARREAU DU TEMPLE AUDITORIUM Under the chairmanship of Fabrice Hergott, director of Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. International speakers. WEDNESDAY, MARCH 30TH THURSDAY MARCH 31TH 10am – 10.30am: Opening 10am – 11am: Drawing and its market 10.30am – 11.30am: Drawing and its collection 11.30am – 12.30am: Drawing and its teaching 11.45am – 12.30am: Artist interview 12.30am – 1pm: Drawing and its teaching, artist interview 1.30pm – 2.30pm: Drawing and its venues 2pm – 3pm: Drawing and its researches I: analysis and interpretation 3pm – 4pm: Drawing and its limits 4.30pm – 5.30pm : Drawing and its exhibition 3.30pm – 4.30pm: Drawing and its researches II: subject and territory 6pm – 6.30pm: Artist interview 5pm – 5.30pm: Artist interview 7pm – 8pm: Drawing and its conservation 6pm – 7pm: Drawing and its collectors Artists, collectors and art world professional Collection, exhibition, creation, conservation, teaching, art market ... two days to debate on drawing Free access upon fair’s tickets presentation, reservations recommended (access on the limit of available seats) Program and contributors: www •drawingnowparis•com AP sympo GB (210x297).indd 1 09/03/16 11:52 BEYOND THE NOTION OF MEDIUM? ince 20 February, the Vancouver Art Gallery has been hosting the biggest exhibition in its history: “MashUp: The Birth Of Modern Culture” — open until 12 June 2016. -

Luxembourg RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018

Luxembourg RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018 KNOWYOURCOUNTRY.COM Executive Summary - Luxembourg Sanctions: None FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries Offshore Finance Centre Higher Risk Areas: Compliance of OECD Global Forum’s information exchange standard US Dept of State Money Laundering assessment Medium Risk Areas: Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: grapes, barley, oats, potatoes, wheat, fruits; dairy and livestock products Industries: banking and financial services, iron and steel, information technology, telecommunications, cargo transportation, food processing, chemicals, metal products, engineering, tires, glass, aluminum, tourism Exports - commodities: machinery and equipment, steel products, chemicals, rubber products, glass Exports - partners: Germany 21.6%, France 15.5%, Belgium 14.5%, UK 5.8%, Italy 5.6%, Switzerland 4.7% (2012) Imports - commodities: minerals, metals, foodstuffs, quality consumer goods Imports - partners: Belgium 30.9%, Germany 23.4%, France 10.4%, US 8.2%, China 7.2%, Netherlands 5.1% (2012) Investment Restrictions: Information unavailable 1 Contents Section 1 - Background ....................................................................................................................... 3 Section 2 - Anti – Money Laundering / Terrorist Financing ............................................................ 4 FATF status ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Compliance with -

Narrative Report on Singapore

NARRATIVE REPORT ON SINGAPORE PART 1: NARRATIVE REPORT Rank: 5 of 133 Background How Secretive? 65 Singapore is ranked fifth in the 2020 Financial Secrecy Index. It has a fairly high secrecy score of 65 and accounts for a huge and growing share – over 5 per cent – of the global market for offshore financial services. Moderatey secretive 0 to 25 This former British colony vies with Hong Kong to be Asia’s leading offshore financial centre. Singapore predominantly serves Southeast Asia while Hong Kong predominantly serves China and North Asia. Many Chinese and North Asian financial investors, however, are deterred by 25 to 50 China’s increasing control over Hong Kong and prefer to park assets in more independent-minded Singapore. Despite the heavily Asian focus, a significant share of banking deposits come from the US and UK. As with so many secrecy jurisdictions, Britain’s influence has been important in 50 to 75 the construction of Singapore’s offshore financial centre. According to the Boston Consulting Group1 in 2015, Singapore held around one-eighth of the global stock of total offshore wealth2, and Exceptionally a 2019 report by the same group found that it hosted $900 billion of secretive 75 to 100 offshore assets – third-highest of any country. An IMF report3 in 2014 estimated that over 95 percent of all commercial banks in Singapore are affiliates of foreign banks, a testament to the country’s extreme dependence on foreign and offshore money. How big? 5.17% The Singapore financial centre is also the region’s largest centre for commodity trading, and in 2014 it overtook Tokyo to become Asia’s largest foreign exchange trading centre – and the world’s third largest after London and New York. -

Freeports As Ecosystems for the Preservation of Fine Art Value and the Acceleration of Related Businesses

Freeports as ecosystems for the preservation of fine art value and the acceleration of related businesses Student Name: Famke A. Loos Student Number: 428404 Supervisor: Prof. dr. F. Vermeylen Master Cultural Economics and Entrepreneurship Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam Master Thesis June 2017 Word count total: 23507 Word count main text: 20805 1 Freeports as ecosystems for the preservation of fine art value and the acceleration of related businesses ABSTRACT This thesis investigated the ecosystems of freeports. Freeports are specialized warehouses for the storage of fine art and collectibles, for both individuals and cultural institutions. Being discrete and confidential in their nature, the role of freeports in the growing contemporary art market is rather unexplored. However, their role becomes increasingly crucial in the growing international art market. Art is more and more perceived as an alternative for financial investment, which further stimulates the international art trade activity. Due to high transaction costs and differences in jurisdictions and rules concerning taxes per country, the physical location of the art transaction is crucial. This thesis aimed to investigate which factors in the art market and related markets drive the emergence and existence of freeports. To obtain an in-depth understanding on freeports and their operations, this thesis applied a contextual approach. First, an extensive literature review was done. Hereafter, interviews, a case study and a site visit were conducted and organized around four themes: the context, the business model, the operations and the impact of freeports. The outcomes revealed that there is no evidence that freeports are unregulated and used for money laundering practices.