Dazzling Color in the Land of the Inca

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of Natural Colours in the Ice Cream Industry

USE OF NATURAL COLOURS IN THE ICE CREAM INDUSTRY Dr. Juan Mario Sanz Penella Dr. Emanuele Pedrazzini Dr. José García Reverter SECNA NATURAL INGREDIENTS GROUP Definition of ice cream Ice cream is a frozen dessert, a term that includes different types of product that are consumed frozen and that includes sorbets, frozen yogurts, non-dairy frozen desserts and, of course, ice cream. In order to simplify its classification, we can consider for practical purposes two different types of frozen desserts: ice cream and sorbets. Ice cream includes all products that have a neutral pH and contain dairy ingredients. While sorbet refers to products with an acidic pH, made with water and other ingredients such as fruit, but without the use of dairy. Additionally, when referring to ice cream, we are not referring to a single type of product, we are actually referring to a wide range of these. Ice cream is a food in which the three states of matter coexist, namely: water in liquid form and as ice crystals, sugars, fats and proteins in solid form and occluded air bubbles in gaseous form, Figure 1. Artisanal ice creams based on natural ingredients which give it its special texture. It should be noted that ice cream is a very complete food from a nutritional point of view since it incorporates in its formulation a wide range of ingredients (sugars, milk, fruits, egg products ...) essential for a balanced diet. Another aspect of great relevance in the manufacture of ice cream is the hedonic factor. Ice cream is consumed mainly for the pure pleasure of tasting it, the hedonic component being the main factor that triggers its consumption, considering its formulation and design a series of strategies to evoke a full range of sensations: gustatory, olfactory, visual and even, of the touch and the ear. -

Effectiveness of Three Pesticides Against Carmine Spider Mite (Tetranychus Cinnabarinus Boisduval) Eggs on Tomato in Botswana

Vol. 17(8), pp. 1088-xxx, August, 2021 DOI: 10.5897/AJAR2021.15591 Article Number: 3489C4F67485 ISSN: 1991-637X Copyright ©2021 African Journal of Agricultural Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJAR Research Full Length Research Paper Effectiveness of three pesticides against carmine spider mite (Tetranychus cinnabarinus Boisduval) eggs on tomato in Botswana Mitch M. Legwaila1, Motshwari Obopile2 and Bamphitlhi Tiroesele2* 1Botswana National Museum, Box 00114, Gaborone, Botswana. 2Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, P/Bag 00114, Gaborone, Botswana. Received 13 April, 2021; Accepted 16 July, 2021 The carmine spider mite (CSM; Tetranychus cinnabarinus Bois.) is one of the most destructive pests of vegetables, especially tomatoes. Its management in Botswana has, for years, relied on the use of pesticides. This study evaluated the efficacy of abamectin, methomyl and chlorfenapyr against CSM eggs under laboratory conditions in Botswana. Each treatment was replicated three times. The toxic effect was evaluated in the laboratory bioassay after 24, 48 and 72 h of application of pesticides. This study revealed that chlorfenapyr was relatively more effective since it had lower LD50 values than those for abamectin and methomyl. It was further revealed that at recommended rates, 90% mortalities occurred 48 h after application of methomyl and chlorfenapyr, while abamectin did not achieve 90% mortality throughout the study period. This implies that abamectin requires extra dosages to achieve mortalities comparable to those of the other two pesticides. The study has found that chlorfenapyr was the most effective insecticide followed by methomyl and then abamectin when applied on CSM eggs. -

Evidence for Synonymy Between Tetranychus Urticae And

Evidence for synonymy between Tetranychus urticae and Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Acari, Prostigmata, Tetranychidae): Review and new data Philippe Auger, Alain Migeon, Edward A. Ueckermann, Louwrens Tiedt, Maria Navajas Navarro To cite this version: Philippe Auger, Alain Migeon, Edward A. Ueckermann, Louwrens Tiedt, Maria Navajas Navarro. Ev- idence for synonymy between Tetranychus urticae and Tetranychus cinnabarinus (Acari, Prostigmata, Tetranychidae): Review and new data. Acarologia, Acarologia, 2013, 53 (4), pp.383-415. 10.1051/ac- arologia/20132102. hal-00979843 HAL Id: hal-00979843 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00979843 Submitted on 16 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License Acarologia 53(4): 383–415 (2013) DOI: 10.1051/acarologia/2013XXXX EVIDENCE FOR SYNONYMY BETWEEN TETRANYCHUS URTICAE AND TETRANYCHUS CINNABARINUS (ACARI, PROSTIGMATA, TETRANYCHIDAE): REVIEW AND NEW DATA Philippe AUGER1,*, Alain MIGEON1, Edward A. UECKERMANN2, 3, Louwrens TIEDT3 and Maria NAVAJAS1 (Received 19 April 2013; accepted 02 June 2013; published online 19 December 2013) 1 Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, UMR CBGP (INRA / IRD / CIRAD / Montpellier SupAgro), Campus international de Baillarguet, CS 30016, F-34988 Montferrier-sur-Lez cedex, France. -

Status of Beekeeping in Ethiopia- a Review

Journal of Dairy & Veterinary Sciences ISSN: 2573-2196 Review Article Dairy and Vet Sci J Volume 8 Issue 4 - December 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Kenesa Teferi DOI: 10.19080/JDVS.2018.08.555743 Status of Beekeeping in Ethiopia- A Review Kenesa Teferi* College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle University, Ethiopia Submission: November 16, 2018; Published: December 06, 2018 *Corresponding author: Kenesa Teferi, College of Veterinary Medicine, Mekelle University, Ethiopia Summary Beekeeping practices is an oldest agricultural activity in Ethiopia. It is a major integral component in agricultural economy of the country. It contributes to the economy of the country directly and indirectly. Its direct contributions are collection of the honey and hive products such as bees wax, and bee colonies whereas its indirect contributions are increase in crop production and conservation of the natural environment through pollination. Despite all the potentials the subsector can offer, the apiculture in Ethiopia has suffered from under estimation of its potential and its role for socioeconomic development. The country’s potential for honey and beeswax production is expected to be 500,000 and 50, 000 tons per year for honey and beeswax respectively, but only approximately about 10% of the honey and wax potential have been tapped, and the commercialization of other high value bee products such as pollen, propolis and bee venom is not yet practiced at a marketable volume, even not yet recognized. Ethiopia ranks ninth in honey and third in beeswax production in the world. All regions of Ethiopia produce honey, but their production potential is different based on suitability of the regions for beekeeping i.e., density of bee’s forages across the region is different and the techniques varies also. -

Global Regulations of Food Colors Each Region Has Its Own Definitions of What Constitutes a Color Additive, with Related Use Requirements and Restrictions

Global Regulations of Food Colors Each region has its own definitions of what constitutes a color additive, with related use requirements and restrictions. Sue Ann McAvoy Sensient Colors LLC t is said, we eat with our eyes . Since antiq - food colors was soon recognized as a threat Iuity, humans have used the color of a to public health. Of concern was that some food to discern its quality. Color provides of the substances were known to be poi - a way to judge ripeness, perceive flavor and sonous and were often incorporated to hide assess quality of food. poor quality, add bulk to foods and to pass Ancient civilizations introduced color off imitation foods as real. into their foods. The ancient Egyptians col - On February 1, 1899, the executive com - ored their food yellow with saffron, and the mittee of the National Confectioners’ Asso - ancient Mayans used annatto to color their ciation published an official circular which Sue Ann McAvoy is food orange-red. Wealthy Romans ate bread was “to throw light upon the vexed question global regulatory scien - that had been whitened by adding alum to of what colors may be safely used in confec - tist for Sensient Food the flour. Color could be used to enhance tionery” as “there may at times be a doubt in Colors LLC. She has worked at Sensient the mind of the honest confectioner as to the physical appearance of the product. since 1979. However, if it made the food appear to be which colors, flavors, or ingredients he may of better quality than it was, that was con - safely use and which he may reject.” This list sidered a deceitful practice. -

Natural Colour Book

THE COLOUR BOOK Sensient Food Colors Europe INDEX NATURAL COLOURS AND COLOURING FOODS INDEX 46 Lycopene 4 We Brighten Your World 47 Antho Blends – Pink Shade 6 Naturally Different 48 Red Cabbage 8 The Colour of Innovation 49 Beetroot – with reduced bluish tone 10 Natural Colours, Colouring Foods 50 Beetroot 11 Cardea™, Pure-S™ 51 Black Carrot 12 YELLOW 52 Grape 14 Colourful Impulses 53 Enocianin 15 Carthamus 54 Red Blends 16 Curcumin 56 VIOLET & BLUE 17 Riboflavin 59 Violet Blends 18 Lutein 61 Spirulina 19 Carrot 62 GREEN 20 Natural Carotene 65 Green Blends 22 Beta-Carotene 66 Copper-Chlorophyllin 24 Annatto 67 Copper-Chlorophyll 25 Yellow/ Orange Blends 68 Chlorophyll/-in 26 ORANGE 69 Spinach 29 Natural Carotene 70 BROWN 30 Paprika Extract 73 Burnt Sugar 32 Carrot 74 Apple 33 Apocarotenal 75 Caramel 34 Carminic Acid 76 BLACK & WHITE 35 Beta-Carotene 79 Vegetable Carbon 36 RED 80 Titanium Dioxide 39 Antho Blends – Strawberry Shade 81 Natural White 40 Aronia 41 Elderberry 83 Regulatory Information 42 Black Carrot 84 Disclaimer 43 Hibiscus 85 Contact Address 44 Carmine 3 INDEX NATURAL COLOURS AND COLOURING FOODS WE BRIGHTEN YOUR WORLD Sensient is as colourful as the world around us. Whatever you are looking for, across the whole spectrum of colour use, we can deliver colouring solutions to best meet your needs in your market. Operating in the global market place for over 100 years Sensient both promises and delivers proven international experience, expertise and capabilities in product development, supply chain management, manufacture, quality management and application excellence of innovative colours for food and beverages. -

Survey of the Pests and Diseases of Honeybees in Sudan

Survey of the pests and diseases of honeybees in Sudan By Mogbel Ahmed Abdalla El-Niweiri B.Sc. (Agric.) Honours, Faculty of Agriculture ١٩٩٨ University of Khartoum A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Agriculture Supervisor Prof. Mohammed S.A. El-Sarrag Department of Crop Protection Faculty of Agriculture University of Khartoum ٢٠٠٤-April ١ Dedication To my beloved family and to all who work in beekeeping ٢ Acknowledgements Thanks and praise first and last to my god the most Gracious and the most Merciful who enabled me to performance this research I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor professor M.S.A.El-Sarrag for introducing me to the subject and for his guidance and patience during my study I am extremely grateful to The beekeepers union in Kabom, south Darfur, El wiam Apiary in Kordfan, and Ais Eldin Elnobi apiary in Halfa for their assistant in inspecting honeybee colonies. I am so grateful to all owners of apiary in Khartoum My deep thanks to my teacher Abu obida O. Ibrahim for his assistance in inspecting imported colonies Thanks are also extended to the following; Insects collection, Agriculture Research Corporation, Sudan Institute for Natural Sciences and Wild life Research Center for their assistance in identification insects, birds, and animals samples. I would like to thank all my colleagues in the Environment and Natural Resources Institute specially thanks due to Satti and Seif Eldin Thanks are also extended to Awad M. E. and Aiad from -

Fuchsias List

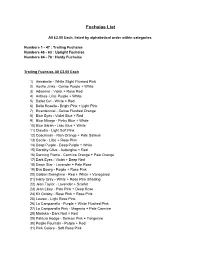

Fuchsias List All £2.00 Each, listed by alphabetical order within categories. Numbers 1 - 47 : Trailing Fuchsias Numbers 48 - 63 : Upright Fuchsias Numbers 64 - 78 : Hardy Fuchsias Trailing Fuchsias All £2.00 Each 1) Annabelle - White Slight Flushed Pink 2) Auntie Jinks - Cerise Purple + White 3) Adrienne - Violet + Rose Red 4) Anthea- Lilac Purple + White 5) Ballet Girl - White + Red 6) Bella Rosella - Bright Pink + Light Pink 7) Bicentennial - Cerise Flushed Orange 8) Blue Eyes - Violet Blue + Red 9) Blue Mirage - Pinky Blue + White 10) Blue Sarah - Lilac Blue + White 11) Claudia - Light Soft Pink 12) Coachman - Rich Orange + Pale Salmon 13) Cecile - Lilac + Rose Pink 14) Deep Purple - Deep Purple + White 15) Dorothy Clive - Aubergine + Red 16) Dancing Flame - Carmine Orange + Pale Orange 17) Dark Eyes - Violet + Deep Red 18) Dawn Star - Lavender + Pale Rose 19) Eva Boerg - Purple + Rose Pink 20) Golden Swingtime - Red + White + Variegated 21) Harry Grey - White + Rose Pink Shading 22) Jean Taylor - Lavender + Scarlet 23) Jean Lilley - Pale Pink + Deep Rose 24) Kit Oxtoby - Rose Pink + Rose Pink 25) Lauren - Light Rose Pink 26) La Campanella - Purple + White Flushed Pink 27) La Campanella Pink - Magenta + Pale Carmine 28) Marinka - Dark Red + Red 29) Patricia Hodge - Salmon Pink + Tangerine 30) Purple Fountain - Purple + Red 31) Pink Galore - Soft Rose Pink 32) Peachy - Peachy Pink 33) Pink Marshmallow - Pinky White 34) Quasar - Lilac Blue + White 35) Red Spider - Deep Crimson + Rose 36) Rose of Denmark - Rosy Purple + White 37) Sir -

Hemiptera: Coccoidea)

Journal of Agricultural Science; Vol. 10, No. 4; 2018 ISSN 1916-9752 E-ISSN 1916-9760 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Efficacy of Libidibia ferrea var. ferrea and Agave sisalana Extracts against Dactylopius opuntiae (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) Rosineide S. Lopes1, Luciana G. Oliveira1, Antonio F. Costa1, Maria T. S. Correia2, Elza A. Luna-Alves Lima3 & Vera L. M. Lima2 1 Agronomic Institute of Pernambuco (IPA), Recife, Brazil 2 Department of Biochemistry, Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife, Brazil 3 Department of Mycology, Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), Recife, Brazil Correspondence: Vera L. M. Lima, Departamento de Bioquímica, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Av. Prof. Moraes Rego, s/n, Cidade Universitária, Recife, PE, CEP: 50670-420, Brazil. Tel: 55-(81)-2126-8576. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 18, 2017 Accepted: January 24, 2018 Online Published: March 15, 2018 doi:10.5539/jas.v10n4p255 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jas.v10n4p255 The research is financed by “Fundação de Amparo à Ciência e Tecnologia do Estado de Pernambuco” (FACEPE), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level -or Education- Personnel) (CAPES), and “Banco do Nordeste do Brasil” (BNB). Abstract The carmine cochineal (Dactylopius opuntiae) is an insect-plague of Opuntia ficus-indica palm crops, causing losses in the production of the vegetable used as forage for the Brazilian semiarid animals. The objective of this work was to analyze the efficacy of plant extracts, insecticides and their combination in the control of D. opuntiae. Leaf and pod extracts of Libidibia ferrea var. -

Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) W

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Technical Bulletins Maine Agricultural and Forest Experiment Station 5-1-1972 TB55: Food Lists of Hippodamia (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) W. L. Vaundell R. H. Storch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/aes_techbulletin Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Vaundell, W.L. and R.H. Storch. 1972. Food lists of Hippodamia (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Life Sciences and Agriculture Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 55. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Technical Bulletins by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Food Lists of Hippodamia (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) W.L. Vaundell R.H. Storch UNIVERSITY OF MAINE AT ORONO LIFE SCIENCES AND AGRICULTURE EXPERIMENT STATION MAY 1972 ABSTRACT Food lists for Hippodamia Iredecimpunctata (Linnaeus) and the genus Hippodamia as reported in the literature are given. A complete list of citations is included. ACKNOWLEDGMENT The authors are indebted to Dr. G. W. Simpson (Life Sciences Agriculture Experiment Station) for critically reading the manus and to Drs. M. E. MacGillivray (Canada Department of Agricull and G. W. Simpson for assistance in the nomenclature of the Aphid Research reported herein was supported by Hatch Funds. Food List of Hippodamia (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) W. L. Vaundell1 and R. H. Storch The larval and adult coccinellids of the subfamily Coccinellinae, except for the Psylloborini, are predaceous (Arnett, 1960). The possi ble use of lady beetles to aid in the control of arthropod pests has had cosmopolitan consideration, for example, Britton 1914, Lipa and Sem'yanov 1967, Rojas 1967, and Sacharov 1915. -

DECEMBER 2018 TREE of the MONTH Scarlet Oak ● Quercus Coccinea RED OAK • BLACK OAK • SPANISH OAK

DECEMBER 2018 TREE OF THE MONTH Scarlet Oak ● Quercus coccinea RED OAK • BLACK OAK • SPANISH OAK Scarlet oak is a medium-sized tree native to eastern and central North America. Scarlet oaks are popular landscape trees because of their fast growth and brilliant autumn color. Scarlet oak grows on sandy and acidic soils, reaching 20-30 meters in height with an open, rounded crown and an alternate branching pattern. Scarlet oaks are fast-growing, shade-intolerant trees that often associate with black oaks (Quercus velutina) and red oaks (Quercus rubra). OPPOSITE BRANCHING PATTERN ALTERNATE BRANCHING PATTERN POINTY LEAVES The leaves are shiny with deep, rounded sinuses, and each lobe has three teeth on the 6p. The leaves turn bright scarlet in autumn. Characteris6cally for oaks, the buds are clustered around the terminal bud at the end of the twig. Each bud is covered with whi6sh hairs on the upper half. The inner bark is pinkish brown and, unusually for oaks, is not bi>er. SPRING BLOOMERS Scarlet oaks Mlower in mid-spring, often May, and bear drooping male catkins (clusters) and female Mlowers singly or in groups of two or three. Acorns develop later in the season in singles or pairs and drop in late Autumn. FOOD FOR ALL Scarlet oak acorns are popular for many wildlife species, from squirrels, mice, and chipmunks, to deer, wild turkeys, and woodpeckers, and jays. TRICKY FELLOW Quercus coccinea is often be confused with the northern red oak (Quercus rubra), black oak (Quercus velutina) and pin oak (Quercus palustris). Tree of the Month is a collabora1on between BEAT, the City of Pi:sfield and Pi:sfield Tree Watch. -

Carmine , C.I. 75470

CARMINE , C.I. 75470 IVD In vitro diagnostic medical device Natural Red 4, Cochineal, Nacarat, aluminum and carminic acid compound For staining mucicarmine and glycogen INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE REF Product code: CAR-P-5 (5 g) CAR-P-10 (10 g) CAR-P-25 (25 g) Introduction Histology, cytology and other related scientific disciplines study the microscopic anatomy of tissues and cells. In order to achieve a good tissue and cellular structure, the samples need to be stained in a correct manner. Carmine is a natural dye whose structure has not been fully explored. However, it is known that it contains aluminum ions, calcium ions to lesser extent, proteins and sometimes silicon. It is often bound with lithium, aluminum or boron to form a complex in order to achieve satisfactory staining results. Carmine is used for various staining procedures and visualization of glycogen and mucous substances, as well as for nuclear staining and vital staining. Product description CARMINE - Powder dye for making solution for histology staining Example of use of Carmine powder dye for detecting glycogen Other sections and reagents that are used in the staining method: absolute ethyl alcohol, methanol potassium chloride, potassium carbonate ammonia Hematoxylin ML Preparing the solutions for staining 1. Carmine stock solution Dissolve 2 g of Carmine powder dye and 5 g of potassium chloride in 60 mL of distilled water while heating the mixture. Add 1 g of potassium carbonate and let it slowly boil (the mixture produces excessive amount of foam). Let it boil for a few minutes as the color changes to dark red.