The Geography of Inter-War (1919-39) Residential Areas on Tyneside: a Study of Residential Growth, and the Present Condition and Use of Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glass Houses of Alfred Alexander Bill Lockhart

The Glass Houses of Alfred Alexander Bill Lockhart Alfred Alexander and his two sons, Alfred (junior) and George, were involved in a series of English bottle factories during the last half of the 19th century and the early 20th century. The firm made a large variety of bottles, including “pale” soda bottles at the Hunslet, Leeds, factory. Some of their bottles were used by U.S. and Canadian bottlers. Histories Blaydon Glass Bottle Co, Blaydon, Durham, England (1854-1860) Yorkshire Bottle Co., London, England (1854-1860) In 1854, Anthony Thatcher established a bottle plant at Blaydon-on-Tyne, Durham, England. The factory was called the Blaydon Bottle Works, although it is unclear whether that was an official name. By at least the following year, Alfred Alexander was the agent for the Yorkshire Bottle Co., with a warehouse at Victoria Wharf on Earl St. and a sales office on Upper Thames St., both in London (McFarlane 2009; North East Bottle Collectors 2011). At some point, possibly from the beginning, Alfred Alexander, Anthony Thatcher, James Battle Austin, and Henry Poole formed a partnership – the Blaydon Glass Bottle Co. – to operate the Blaydon plant. We have discovered virtually nothing about the operation of the factory during this period, although the partnership was formed as “Bottle Manufacturers and Bottle Merchants.” Thatcher retired, so the partnership dissolved on July 2, 1860 (McFarlane 2009). Alexander, Austin & Poole, Blaydon (1860-1861) With the retirement of Thatcher, the remaining three – Alexander, Austin & Poole – operated the Blaydon plant under this name for a brief period. The Yorkshire Bottle Co. -

Fernyhough Hall Hebburn Fernyhough Hall

Fernyhough Hall Hebburn Fernyhough Hall About us Nestled in the heart of Hebburn, Fernyhough Hall is pleasantly located in a lovely residential area and is close to all local amenities. It has 28 one-bedroomed apartments, four two bedroomed apartments and four bungalows. To fully appreciate all this Housing Plus accommodation has to offer, we recommend an accompanied viewing with one of our Housing Plus Officers. Apartment facilities: • Central heating and hot water (included in rent charges) • Separate kitchen • Lounge • Walk in shower • Bedroom(s) Our Housing Plus Officers are available Monday to Friday during office hours. Outside of office hours calls are answered through the emergency pull-cord system. Fernyhough Hall is central to local shops, Hebburn Housing Office, Doctor’s surgeries and pharmacies. It has great transport links from Ushaw Road / Victoria Road to the town centre and surrounding areas. It is also within walking distance to Hebburn Metro Station. 2 Fernyhough Hall Other facilities: • Secure door entry system, with intercom to every apartment • Emergency pull-cord system in every apartment • Communal Lounge • Guest room (available for a small charge) • On-site laundry (2 washing machines, 2 dryers- included in rent) • Lift access to all three floors Housing Plus apartments offer you independent living with the added benefit of a safe and secure environment. For further information please call us on 0300 123 6633 or email [email protected] Our Housing Plus Officers are available Monday to Friday during office hours. Outside of office hours calls are answered through the emergency pull-cord system. Fernyhough Hall is central to local shops, Hebburn Housing Office, Doctor’s surgeries and pharmacies. -

S844 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

S844 bus time schedule & line map S844 Allerdene - Blaydon View In Website Mode The S844 bus line (Allerdene - Blaydon) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Allerdene: 3:40 PM (2) Blaydon: 7:30 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest S844 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next S844 bus arriving. Direction: Allerdene S844 bus Time Schedule 32 stops Allerdene Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday Not Operational St Thomas More Catholic School, Blaydon 14 Croftdale Road, Blaydon Tuesday Not Operational Blaydon Bank-Croftdale Road, Blaydon Wednesday Not Operational 42 Bowland Crescent, Blaydon Thursday 3:40 PM Blaydon Bank-Lawrence Court, Blaydon Friday 3:40 PM 8 Lawrence Court, Blaydon Saturday Not Operational Chainbridge Road-Whiteley Road, Blaydon Riverside Way-Clasper Way, Metrocentre Riverside Way, Metrocentre S844 bus Info Direction: Allerdene Handy Drive-Bus Depot, Metrocentre Stops: 32 Trip Duration: 35 min St Omers Road, Dunston Line Summary: St Thomas More Catholic School, Railway Street, Gateshead Blaydon, Blaydon Bank-Croftdale Road, Blaydon, Blaydon Bank-Lawrence Court, Blaydon, Chainbridge Colliery Road, Dunston Road-Whiteley Road, Blaydon, Riverside Way-Clasper Way, Metrocentre, Riverside Way, Metrocentre, Clockmill Road, Teams Handy Drive-Bus Depot, Metrocentre, St Omers Road, Dunston, Colliery Road, Dunston, Clockmill Road, Derwentwater Road-Teams Bridge, Teams Teams, Derwentwater Road-Teams Bridge, Teams, Derwentwater Road-Pitz, Teams, Johnson Street, -

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays Middlesbrough d - - 0832 - - 0931 - - 1031 - Hartlepool d - - 0903 - - 1001 - - 1101 - Horden d - - 0914 - - 1012 - - 1112 - Sunderland d - - 0932 - - 1030 - - 1130 - Newcastle a - - 0951 - - 1050 - - 1150 - d 0845 0930 0955 1016 1035 1055 1115 1133 1155 1215 Dunston - 0935 - 1021 - - 1121 - - 1220 MetroCentre a 0852 0939 1002 1025 1043 1102 1124 1141 1202 1224 d 0853 - 1003 - - 1103 - - 1203 - Blaydon 0857 - 1007 - - - - - 1207 - Wylam 0903 - 1013 - - 1111 - - 1213 - Prudhoe 0908 - 1017 - - 1115 - - 1218 - Stocksfield 0912 - 1022 - - 1120 - - 1222 - Riding Mill 0917 - 1026 - - 1124 - - 1227 - Corbridge 0921 - 1030 - - 1128 - - 1231 - Hexham a 0927 - 1036 - - 1134 - - 1237 - d 0927 - 1037 - - 1135 - - 1237 - Haydon Bridge 0937 - 1046 - - 1144 - - - - Bardon Mill 0943 - 1052 - - 1150 - - - - Haltwhistle 0950 - 1100 - - 1158 - - 1256 - Brampton 1005 - 1115 - - - - - 1311 - Wetheral 1014 - 1124 - - - - - 1320 - Carlisle a 1024 - 1134 - - 1232 - - 1330 - Middlesbrough d - 1131 - - 1230 - - 1331 - - Hartlepool d - 1201 - - 1300 - - 1401 - - Horden d - 1212 - - 1311 - - 1412 - - Sunderland d - 1230 - - 1329 - - 1430 - - Newcastle a - 1250 - - 1349 - - 1450 - - d 1235 1255 1315 1333 1355 1415 1428 1455 1515 1535 Dunston - - 1321 - - 1420 - - 1521 - MetroCentre a 1243 1302 1324 1341 1402 1424 1436 1502 1524 1543 d - 1303 - - 1403 - - 1503 - - Blaydon - - - - 1407 - - - - - Wylam - 1311 - - 1413 - - 1511 - - Prudhoe - 1315 - - 1418 - - 1515 - - Stocksfield - 1320 - - 1422 - - 1520 - - Riding Mill -

Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) Request 764/17 - Front Desk

NOT PROTECTIVELY MARKED Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) Request 764/17 - Front desk Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line 3 Address Line 4 Postcode 2012 17.7.17 Gillbridge Police Station Livingstone Road Sunderland SR1 3AW 24/7 Station Sold Replaced by Sunderland City Centre Base Sunderland City Centre Base Waterloo Place Sunderland SR1 3HS N/A 24/7 Farringdon Hall Police Station Primate Road Sunderland SR3 1TQ 9 - 5 Station Sold Replaced by Farringdon NPT Base Farringdon NPT Base Farringdon Fire Northmoor Road Sunderland SR3 1TJ N/A 10 – 2 Station Southwick Police Station Church Bank Southwick Sunderland SR5 2DU 9 - 5 8 - 8 Washington Police Station The Galleries Washington NE38 7RY 24/7 9 -5 Houghton Police Station Dairy Lane Houghton le Spring Sunderland DH4 5BH 9 - 5 10 -2 South Shields Police Station Millbank South Shields NE33 1RR 24/7 8 - 8 Hebburn Police Station Victoria Road East Hebburn NE31 1XF 9 - 5 Station Sold Replaced by Hebburn Hub Front Office, Replaced by South Shields Hebburn Hub Front Office Hebburn Hub Hebburn NE31 2QP N/A Closed Gateshead Police Station High Street West Gateshead NE8 1BN 24/7 8 - 8 Whickham Police Station Front Street Whickham Gateshead NE16 4HE 8 - 9 - 5 Midnight North Shields Police Station Upper Pearson North Shields NE30 1AB 9 - 5 9 - 5 Street Whitley Bay Police Station Laburnum Avenue Whitley Bay NE26 2HY 9 - 5 Station Sold Replaced by Whitley Bay NPT Base Whitley Bay NPT Base Unit 21 Park View Shopping Whitley Bay NE26 2TJ NA 9 -5 Centre Middle Engine Lane Police Station Middle -

Map Key Traffic Signs Bike Shops Places of Interest South Shields

Traffic Signs Map Key 64 64 Bike Shops Some traffic signs that you may come across when you are cycling through National Cycle Network the area. A-S Cycles Halfords Bike Hut off-road cycle path Cycle shop 44 St. Aidan’s Road, Unit 3 Trimdon Street, South Shields NE33 2HD Sunderland National Cycle Network No entry on-road routes Tel: 0191 456 3133 Tel: 0191 514 0843 Cycle parking Barrie Hopkirk’s Cycle Centre Hardistry Cycles Traffic-free path Motor vehicles prohibited 248 Shields Road, 5-7 Union Road, Toucan crossing (cycles permitted) Byker, Newcastle NE6 1DX Byker, Newcastle NE6 1DH Path or footway where Tel: 0191 265 1472 Tel: 0191 265 8619 you should walk your bike Conway Cycles Pedal Inn Pedestrian crossing No cycling 63 63 Bridleway / Rough track 12 Salem Street, 172 Albert Road, A number of our traffic free paths are South Shields NE33 1HH Jarrow NE32 5JA Bridleways and Shared paths which are Tel: 0191 455 3129 Tel: 0191 428 6190 enjoyed by Horse riders and pedestrians too. Railway station Cyclists must show respect to other users by Shared route giving way at all times, slowing down and for cyclists & Cycle World Peter Darke Cycles using their bell before passing pedestrians 118 High Street West, 1-2 John Street, Level crossing Sunderland SR1 1TR Sunderland SR1 1DX Signposted on-road Tel: 0191 565 8188 or 514 1974 Tel: 0191 510 8155 Route to be used cycle route www.darkecycles.com by cycles only Halfords Metro station Road links Station Road, Spokes Road links are other possible road Millbank, South Shields NE33 1ED connections which can provide useful routes 38 Nile Street, across the area, but which are shared with Segregated cycle Tel: 0191 427 1600 North Shields NE29 0DB varying amounts and speeds of traffic. -

Gateshead Libraries

Below is a list of all the places that have signed up to the Safe Places scheme in Gateshead. Gateshead Libraries March 2014 Birtley Library, Durham Road, Birtley, Chester-le-Street DH3 1LE Blaydon Library, Wesley Court, Blaydon, Tyne and Wear NE21 5BT Central Library, Prince Consort Road, Gateshead NE8 4LN Chopwell Library, Derwent Street, Chopwell, Tyne and Wear NE17 7HZ Crawcrook Library, Main Street, Crawcrook, Tyne and Wear NE40 4NB Dunston Library, Ellison Road, Dunston, Tyne and Wear NE11 9SS Felling Library, Felling High Street Hub, 58 High Street, Felling NE10 9LT Leam Lane Library, 129 Cotemede, Leam Lane Estate, Gateshead NE10 8QH The Mobile Library Tel: 07919 110952 Pelaw Library, Joicey Street, Pelaw, Gateshead NE10 0QS Rowlands Gill Library, Norman Road, Rowlands Gill, Tyne & Wear NE39 1JT Whickham Library, St. Mary's Green, Whickham, Newcastle upon Tyne NE16 4DN Wrekenton Library, Ebchester Avenue, Wrekenton, Gateshead NE9 7LP Libraries operated by Constituted Volunteer Groups Page 1 of 3 Lobley Hill Library, Scafell Gardens, Lobley Hill, Gateshead NE11 9LS Low Fell Library, 710 Durham Road, Low Fell, Gateshead NE9 6HT Ryton Library is situated to the rear of Ryton Methodist Church, Grange Road, Ryton Access via Hexham Old Road. Sunderland Road Library, Herbert Street, Gateshead NE8 3PA Winlaton Library, Church Street, Winlaton, Tyne & Wear NE21 6AR Tesco, 1 Trinity Square, Gateshead, Tyne & Wear NE8 1AG Bensham Grove Community Centre, Sidney Grove, Bensham, Gateshead,NE8 2XD Windmill Hills Centre, Chester Place, Bensham, -

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

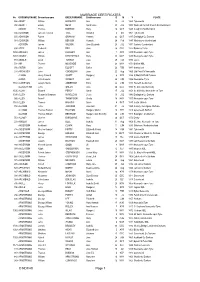

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

111077NCJRS.Pdf

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ' "-1- ~ : • ,. - .. _.~ , . .• • • //1 077 111077 U.S. Department of Justice Nationat Institute of Justice ThIs document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating it. Points of view or opinions stated in this document are Ihose of the authors and do not necessarily represent the offIcial position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. PermiSSIon to reproduce thIs copyrighted material has been granted by Northumbria Poljce Department to the National Crimmal Justice Reference Service (NCJHS). Further reproductIon outsIde of the NCJRS system reqUIres p,,,mls, sIan of the copYright owner. Force Headquatters Ponteland Newcastle upon Tyne April 1988 To The Right Honourable the Secretary of state for the Home Department and to the Chairman and Members of the Northumbria Police Authority. Sir. Mr Chairman. Ladies and Gentlemen. The following report on the policing of Northumbria has been prepared in compliance with Sections 12( I) and 30( 2) of the Police Act 1964. I have the honour to be. Sir, Ladies and Gentlemen, Your obedient servant. Sir Stanley E Bailey. CBE. QPM. DL. CBIM Chief Constable 2 Acknowledgements of Public Motor and Motorcycle Patrols 71 Assistance 88 Multi-agency Initiatives 54 Adm1n!stration 88 NALGO 89 Annual Inspection of the Force 89 Newcastle 19 AppencUces A· R (Statistics) 97 Northern 13 Casualty Bureau 61 North Tyneslde and Blyth 23 Central Ticket Office 73 Northumbria Crime Squad 47 The ChIef -

Blaydon Ward Factsheet

Blaydon Ward Factsheet Blaydon ward is located in the West of Gateshead along with four other wards – Chopwell and Rowlands Gill, Crawcrook and Greenside, Ryton, Crookhill and Stella, and Winlaton and High Spen. Blaydon Precinct offers a range of shopping facilities and services and is the main bus terminal for the area with links to the Town Centre and Newcastle. The area also benefits from Blaydon Railway Station on the Newcastle to Carlisle railway line. There is a large industrial estate to the north east along the riverbank, whilst the residential areas lie mainly to the south west of the ward. Housing is of mixed age and tenure with just over half private ownership and much of the remainder Council owned. Neighbourhood Deprivation (Overall IMD 2015): To view an interactive map of IMD 2015 and its domains visit www.gateshead.gov.uk/imd Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2018 Area/Population Population, ONS Mid Year Ward Population Estimates (Current data: 2017) BME Group, ONS Census (Current data: 2011) Area: Population: Males: Females: 5.4km² / 2.1mi² 10198 4853 5345 0-19: 16-64: 65+: BME Group: 2386 (23.4%) (22.1%) 6474 (63.5%) (63.2%) 1783 (17.5%) (19.3%) 216 (2.1%)(3.7%) Community Safety All Crime, Northumbria Police (Current data: Jul-Sep 18) Rate per 1,000 pop Current data for all wards: RC&S C&G WS&S W&HS LF DH&WE W&LL C&RG Ch P&H Bl WN&W GH Sa De LH&B Bi D&T La Fe HF WN Br 8 10 13 16 18 18 19 21 22 23 25 25 28 30 33 34 34 35 35 38 40 41 65 40 Trend data for Blaydon and Gateshead average 20 -

Who Runs the North East … Now?

WHO RUNS THE NORTH EAST … NOW? A Review and Assessment of Governance in North East England Fred Robinson Keith Shaw Jill Dutton Paul Grainger Bill Hopwood Sarah Williams June 2000 Who Runs the North East … Now? This report is published by the Department of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Durham. Further copies are available from: Dr Fred Robinson, Department of Sociology and Social Policy, University of Durham, Durham DH1 3JT (tel: 0191 374 2308, fax: 0191 374 4743; e-mail: [email protected]) Price: £25 for statutory organisations, £10 for voluntary sector organisations and individuals. Copyright is held collectively by the authors. Quotation of the material is welcomed and further analysis is encouraged, provided that the source is acknowledged. First published: June 2000 ISBN: 0 903593 16 5 iii Who Runs the North East … Now? CONTENTS Foreword i Preface ii The Authors iv Summary v 1 Introduction 1 2 Patterns and Processes of Governance 4 3 Parliament and Government 9 4 The European Union 25 5 Local Government 33 6 Regional Governance 51 7 The National Health Service 64 8 Education 92 9 Police Authorities 107 10 Regeneration Partnerships 113 11 Training and Enterprise Councils 123 12 Housing Associations 134 13 Arts and Culture 148 14 Conclusions 156 iii Who Runs the North East … Now? FOREWORD Other developments also suggest themselves. At their meeting in November 1998, the The present work is admirably informative and trustees of the Millfield House Foundation lucid, but the authors have reined in the were glad to receive an application from Fred temptation to explore the implications of what Robinson for an investigation into the they have found. -

Monkton Fell and South Hebburn260.09KB

Tyne Tunnel Getting to the health walks Where to find Hebburn’s WAY ROAD All the walks start on Mill Lane near the Swarm sculpture, which is near the entrance B1297 WAGON healthy walks to the developing Monkton Business Park. JARROW METRO Local buses serve Finchale Avenue and Mill Lane on a regular basis from both Jarrow CTORIA ROAD A185 VI EAST and Heworth. The nearest Metro Station is at Hebburn, which is about a mile from the to South Shields start. Contact North East Travel Line 0870 608 2608 for more information. B C 1 A E T A 1 5 85 S M Route 4 1 N E 6 W P B Getting around the health walks Y HEBBURN D E Y A19 T A L O L O R P R K A The majority of the paths are fairly flat and there are no steps on any of the walks, but R A A I R E R K V E there are some steep slopes near the Monkton Burn. The surface is mostly tarmac or O R V N T O I U C R I A loose stone but there is a grass section across the playing field in walk 2. E V Route 2 D 5 8 The walks have been designed with everyone in mind, including people with to 1 A Route 1 to South Heworth Shields pushchairs and wheelchair users. M Route 3 I A185 LL A194 L A A194 N E Monkton Fell Community Environmental Action project B NE 1 LA NEWCASTLE TO 3 M This project was set up to encourage the people of Hebburn to have a greater 0 EA SUNDERLAND RAILWAY PELAW 6 L Start/finish 94 involvement in their local environment, in particular the area of countryside in south A1 F all routes A19 EL Hebburn known as Monkton Fell.