Poetic Play Communities: Bpnichol's Fraggle Rock Screenplays By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

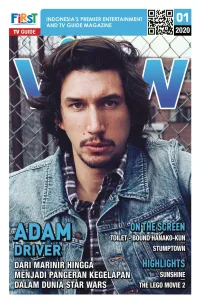

View 202001.Pdf

ON THE SCREEN Premieres Wednesday, January 8 10.10 PM juga adik lelakinya. Di lain sisi, Dex Parios juga berjuang dari rasa traumatis yang ia dapat setelah bertugas sebagai marinir di Afghanistan. Saat itu Premieres, Tuesday ketika ia sedang bertugas sebagai intelijen militer, Dex Parios mengalami ledakan yang membuatnya January 21, 8 PM terluka, dan harus kehilangan orang yang ia cintai. Sementara ia meninggalkan pekerjaannya, ia Sebuah serial televisi Amerika yang pun memutuskan untuk bekerja serabutan demi bertemakan drama kriminal. Dibintangi menghidupi dirinya dan juga adiknya. Hingga oleh Cobie Smulders, Jake Johnson dan pada saatnya, Dex Parios bekerja sebagai Michael Ealy. penyelidik swasta dimana ia bertugas untuk menyelidiki masalah yang tidak bisa dicampuri Teks: Klement Galuh A oleh kepolisian. Dalam perjuangannya tersebut, ia pun mendapat dukungan dari seorang detektif ada serial ini bercerita tentang Dex Parios, bernama Miles Hoffman dan juga Gray McConnel seorang veteran militer cerdas, yang hidup yang mempekerjakan saudara lelaki Dex Parios di P dan berjuang untuk menghidupi dirinya dan bar miliknya. (LMN/MHG/LMN/FIO) 4 Acara “Sacred Sites”, kita diajak untuk mengunjungi tempat-tempat bersejarah yang masih menjadi rahasia dan misteri bagi umat manusia. Kita akan diajak untuk menemukan jawaban-jawaban tersebut melalui acara ini. Teks: Klement Galuh A pakah benar legenda raja Arthur nyata adanya? Pertanyaan tersebut akan dikupas menggunakan A terobosan ilmiah dan penelitian arkeologis untuk membawa kita kepada perspektif baru ke beberapa lokasi religi yang luar biasa, namun juga misterius. Dalam setiap episodenya, acara ini akan berfokus pada satu situs dan mengeksplorasi situs tersebut. Dimulai dari orang-orang yang membangunnya, hingga menjawab pertanyaan mendasar dari orang-orang yang melihat bangunan tersebut. -

Mrts 4450/5660.001: It's Not Tv, It's Hbo!

MRTS 4450/5660.001: IT’S NOT TV, IT’S HBO! University of North Texas Fall 2020 Professor: Jennifer Porst Email: [email protected] Class: T 2:30-5:20P Office Hours: By appointment Course Description: Since its debut in the early 1970s, HBO has been a powerhouse in American television and film. They regularly dominate the nominations for Emmy and Golden Globe awards, and their success has profoundly affected the television and film industries and the content they produce. Through an examination of the birth and development of HBO, we will see what a closer analysis of the channel can tell us about television, Hollywood, and American culture over the last four decades. We will also look to the future to see what HBO might become in the increasingly global and digital television landscape. Student Learning Goals: This course will provide students with an opportunity to: • Understand the industrial conditions that led to the birth and success of HBO • Gain insight into the contemporary challenges and opportunities faced by the media industries • Develop critical thinking skills through focused analysis of readings and HBO content • Communicate clearly and confidently in class discussion and presentations Required Texts: 1. Edgerton, Gary R. and Jeffrey P. Jones, Eds. The Essential HBO Reader. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008. Available as an e-book via the UNT Library website. 2. Subscription to HBO Go/Now 3. Additional required readings and screenings will be available for free through the class website. 4. Students will need to register for use of the Packback Questions site, which should cost between $10- 15 for the semester. -

Jim Henson's Fantastic World

Jim Henson’s Fantastic World A Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department Produced in conjunction with Jim Henson’s Fantastic World, an exhibition organized by The Jim Henson Legacy and the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service. The exhibition was made possible by The Biography Channel with additional support from The Jane Henson Foundation and Cheryl Henson. Jim Henson’s Fantastic World Teacher’s Guide James A. Michener Art Museum Education Department, 2009 1 Table of Contents Introduction to Teachers ............................................................................................... 3 Jim Henson: A Biography ............................................................................................... 4 Text Panels from Exhibition ........................................................................................... 7 Key Characters and Project Descriptions ........................................................................ 15 Pre Visit Activities:.......................................................................................................... 32 Elementary Middle High School Museum Activities: ........................................................................................................ 37 Elementary Middle/High School Post Visit Activities: ....................................................................................................... 68 Elementary Middle/High School Jim Henson: A Chronology ............................................................................................ -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007. -

Doozers,” Continue to “Do, Do, Do It” on Hulu with All New Episodes Streaming May 25Th

JIM HENSON’S “DOOZERS,” CONTINUE TO “DO, DO, DO IT” ON HULU WITH ALL NEW EPISODES STREAMING MAY 25TH Hulu’s Original Kids Series Returns for a Second Season with New Episodes Featuring Problem- solving Methods and Encouraging Team Work and Creativity Hollywood, CA (May 7, 2018) – They’re green, they’re cute and they’re awesome – they’re the DOOZERS! Hulu’s first Original Series for kids will be back for Season 2 with all new original episodes starting May 25th, from The Jim Henson Company (Dot, Splash and Bubbles, Word Party, Dinosaur Train). DOOZERS is an animated preschool series for kids featuring four best friends who live in Doozer Creek, a wonderful blending of a fantastical, modern and eco-friendly community. Dubbed “the Pod Squad,” Spike, Molly Bolt, Flex and Daisy Wheel bounce from one fabulous kid adventure to the next. Like a scout troop, the Pod Squad engages in exciting projects and has a blast playing together. The series celebrates the spirit of being an innovator and inspires all kids to have an “I can do it” attitude. DOOZERS features a ground-breaking design thinking curriculum, which is part of an overall STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art, math) initiative. These DOOZERS are DOERS and put their ideas into action! “The new season of DOOZERS continues to inspire and encourage invention and innovation,” said Halle Stanford, President of Television for The Jim Henson Company. “Parents can rest assured that their little DOOZER fans will continue to learn critical and creative thinking skills as they follow the Pod Squad on their playful adventures.” The Jim Henson Company has appointed Canada’s DHX Media to provide production and animation services for the series. -

The Architect's Dilemma: Searching for an Architecture of Pleasure +

THE ARCHITECT’S DILEMMA 1 The Architect’s Dilemma: Searching for an Architecture of Pleasure + Sustenance AMANDA SCHMALTZ Miami University INTRODUCTION amount of organizational skill.”3 Where architecture and the culinary arts diverge, as Architect Donald Kunze writes, “Because food indicated by Collins, is due to the fact that and architecture are superficially very architects have forgotten to judge their work different but really closely connected, the with “degrees of excellence” and have become method that explores connections has to overly concerned with “being ‘contemporary’ cover a broad and discontinuous ground.”1 or ‘reactionary,’ instead of whether their work Architecture and the culinary arts are both was good or bad.”4 The concept of good practiced and appreciated by people who seek versus bad helps shape the way humans to improve the ways in which our most basic biologically and psychologically perceive their physiological needs are met. The two environment. disciplines, as the sublimation of mere food and shelter are creative solutions that have Architect Marco Frascari critiques mainstream the ability to provide pleasure and therefore contemporary architecture by comparing the sustain and enrich our everyday lives. I would built products of Modern and Post-Modern argue that the culinary arts have been much theories to fast food. Fast food is here being more widely successful than architecture at used as something that is generally accomplishing this charge. This paper surveys recognized as unhealthy or “bad for us.” a selection of connections between the two Frascari contends that these theories’ ultimate fields as a means of discovering what might goals are to “produce buildings that ‘look be learned in the field of architecture from good’ over a predetermined life span” and gastronomic pursuits. -

Back at 'Last'

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 27, 2016 5:00:34 PM Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment for the week of March 5 - 11, 2016 Some of the cast of “The Last Man on Earth” Back at HMA.HMA. .Car .Care . Systems . ‘Last’ WASH WINTER AWAY HMA Car Care AT1 x 5 HMA. 978.744.4444 Superb polishing, interiors, great body work and more. 24/7 Car Wash HMACARCARE.COM 72 North St. (Rte. 114), Salem, MA Newspaper Advertising Works! Massachusetts’ First Credit Union THIS Located at 370 HighlandSt. Avenue, Jean's Salem Credit Union AD SPOTET Filler 3 x 3 COULD1 BE x YOURS. 3 Serving over 15,000 Members • A Part of your Community since 1910 Ask us about very economical advertising in Saturday’s Salem News TV Spotlight Supporting over 60 Non-Profit Organizations & Programs (with an option to print a deeply ) discounted ad in The Salem News Serving the Employees of over 40 Businesses Contact: Glenda Duchesneau 978.219.1000 • www.stjeanscu.com 978-338-2540 • [email protected] Offices also located in Lynn, Newburyport & Revere Federally Insured by NCUA FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 27, 2016 5:00:36 PM 2 • Salem News • March 5 - 11, 2016 Where there’s a Will Video Will Forte’s post-apocalyptic comedy returns from hiatus releases By Jacqueline Spendlove scouring the continent for other sur- nale to seven — plus Phil’s es- With the emergence of new char- companion worms die off one by TV Media vivors of a virus that has wiped out tranged astronaut brother, Mike (Ja- acters being more of a season 1 fo- one, but just as he’s about to com- most of humanity, and just after giv- son Sudeikis, “We’re the Millers,” cus, the first half of the current sea- mit suicide by jettisoning himself hristmas break and then ing up, he meets the good-hearted 2013), who’s stranded out in space, son has followed the group as it into space, he spots a newborn some! It’s been almost three (albeit profoundly irritating) Carol unbeknownst to anyone. -

365Ink98.Pdf

It doesn’t feel very Christmasy to me. I’m not even about it, but I’m in a bad mood there, too. Of all sure if that’s how you spell Christmasy, or if that’s the people to let me down, it was the Marines. really even a word. Maybe it’s because 2009 has Not the local Marine vets. They’ve been great. I been such a spectacular turd of a year. It seems expect nothing less. But the big cities around us like everyone is broke. Everyone is in a bad mood where actual Marines run the program. I get the or everyone is dying. I don’t even want to remem- feeling they look at the Toys program like they just ber how many of my friends all lost our dads in pulled kitchen duty. I offered huge loads of ex- the last year. While Dubuque has weathered the cess books and toys to the Quad Cities, who said financial fallout fairly well, it seems like the bah- they wanted them. Three weeks and a half-dozen humbug mood that comes with the fallout has still phone calls and e-mails later, they say they don’t managed to settle over our little town. Or maybe have to time or people to come to Dubuque to I’m just watching too much news. I’m not sure if get the six pallets of free stuff. That’s a three-hour people are in a bad mood or if there is just mass round trip folks. -

A Consumer-Based Examination of Netflix Inc. Original Programming and Streaming Strategy

Streaming is the New Black: A Consumer-based Examination of Netflix Inc. Original Programming and Streaming Strategy A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Lindsay B. Strott in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Television Management March 2015 © Copy Right 2015 Lindsay B. Strott. All Rights Reserved i Acknowledgements Thank you to my thesis advisor Dr. Lydia Timmins and program director Al Tedesco for your guidance throughout my studies and the thesis writing process. I would also like to thank my family, friends, and classmates for their support and encouragement. ii Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................. vii List of Figures ........................................................................................................... viii List of Appendices ...................................................................................................... xi Abstract ...................................................................................................................... xii Chapter 1 : Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Statement of the Problem ........................................................................................ 4 1.3 Background ............................................................................................................ -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers in Bessemer

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; BLACKISH) -

Inventory to Archival Boxes in the Motion Picture, Broadcasting, and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress

INVENTORY TO ARCHIVAL BOXES IN THE MOTION PICTURE, BROADCASTING, AND RECORDED SOUND DIVISION OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Compiled by MBRS Staff (Last Update December 2017) Introduction The following is an inventory of film and television related paper and manuscript materials held by the Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress. Our collection of paper materials includes continuities, scripts, tie-in-books, scrapbooks, press releases, newsreel summaries, publicity notebooks, press books, lobby cards, theater programs, production notes, and much more. These items have been acquired through copyright deposit, purchased, or gifted to the division. How to Use this Inventory The inventory is organized by box number with each letter representing a specific box type. The majority of the boxes listed include content information. Please note that over the years, the content of the boxes has been described in different ways and are not consistent. The “card” column used to refer to a set of card catalogs that documented our holdings of particular paper materials: press book, posters, continuity, reviews, and other. The majority of this information has been entered into our Merged Audiovisual Information System (MAVIS) database. Boxes indicating “MAVIS” in the last column have catalog records within the new database. To locate material, use the CTRL-F function to search the document by keyword, title, or format. Paper and manuscript materials are also listed in the MAVIS database. This database is only accessible on-site in the Moving Image Research Center. If you are unable to locate a specific item in this inventory, please contact the reading room.