Implications for HIV/AIDS Infection and Control in a Metropolitan City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Registered Hospitality and Tourism Enterprises As At

REGISTERED HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM ENTERPRISES AS AT MARCH, 2020 NATURE OF S/N NAME OF ESTABLISHMENTS ADDRESS/LOCATION BUSINESS 1 TOURIST COMPANY OF NIG(FEDERAL PALACE HOTEL 6-8, AHMADU BELLO STREET, LAGOS HOTEL PLOT, 1415 ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA ST. V/I 2 EKO HOTELS & SUITES LAGOS HOTEL 3 SHERATON HOTEL 30, MOBOLAJI BANK ANTHONY WAY IKEJA. HOTEL 4 SOUTHERN SUN IKOYI HOTEL 47, ALFRED REWANE RD, IKOYI LAGOS HOTEL 5 GOLDEN TULIP HOTEL AMUWO ODOFIN MILE 2 HOTEL 6 LAGOS ORIENTAL HOTEL 3, LEKKI ROAD, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS HOTEL 1A, OZUMBA MBADIWE STREE, VICTORIA 7 RADISSON BLU ANCHORAGE HOTEL ISLAND, LAGOS HOTEL 8 FOUR POINT BY SHERATON PLOT 9&10, ONIRU ESTATE, LEKKI HOTEL 9 MOORHOUSE SOFITEL IKOYI 1, BANKOLE OKI STREET, IKOYI HOTEL MILAND INDUSTRIES LIMITED (INTERCONTINETAL 10 HOTEL) 52, KOFO ABAYOMI STR, V.I HOTEL CBC TOWERS, 8TH FLOOR PLOT 1684, SANUSI 11 PROTEA HOTEL SELECT IKEJA FAFUNWA STR, VI HOTEL 12 THE AVENUE SUITES 1390, TIAMIYU SAVAGE VICTORIA ISLAND HOTEL PLOT, 1415 ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA ST. V/I 13 EKO HOTELS & SUITES (KURAMO) LAGOS HOTEL PLOT, 1415 ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA ST. V/I 14 EKO HOTELS & SUITES (SIGNATURE) LAGOS HOTEL 15 RADISSON BLU (FORMERLY PROTEA HOTEL, IKEJA) 42/44, ISAAC JOHN STREET, G.R.A, IKEJA HOTEL 16 WHEATBAKER HOTEL (DESIGN TRADE COMPANY) 4, ONITOLO STREET, IKOYI - LAGOS HOTEL 17 PROTEA (VOILET YOUGH)PARK INN BY RADISSON VOILET YOUGH CLOSE HOTEL 18 BEST WESTERN CLASSIC ISLAND PLOT1228, AHAMDADU BELLO WAY, V/I HOTEL 19 LAGOS AIRPORT HOTEL 111, OBAFEMI AWOLOWO WAY, IKEJA HOTEL 20 EXCELLENCE HOTEL & CONFERENCE CENTRE IJAIYE OGBA RD., OGBA, LAGOS HOTEL 21 DELFAY GUEST HOUSE 3, DELE FAYEMI STREET IGBO ELERIN G H 22 LOLA SPORTS LODGE 8, AWONAIKE CRESCENT, SURULERE G H 23 AB LUXURY GUEST HOUSE 20, AKINSOJI ST. -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MAY 2015 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 5636 038404 IBADAN DOYEN NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 24 3 0 0 0 3 27 5636 039839 ABEOKUTA NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 45 6 0 0 -11 -5 40 5636 041287 LAGOS SURULERE NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 8 7 1 0 0 8 16 5636 041434 LAGOS ISOLO NIGERIA 404 B1 4 11-2014 41 0 0 0 0 0 41 5636 045263 IBADAN BODIJA NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 19 9 0 0 0 9 28 5636 045982 OTA DOYEN NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 36 4 0 0 -1 3 39 5636 053828 SATELLITE CENTRAL NIGERIA 404 B1 4 04-2015 29 6 1 0 -8 -1 28 5636 053886 LAGOS NEW LAGOS NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 18 2 0 0 0 2 20 5636 054754 IBADAN HILL-TOP NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 13 1 0 0 0 1 14 5636 055191 OLUMO NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 10 1 0 0 -1 0 10 5636 055401 OKOTA NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 31 1 0 0 -11 -10 21 5636 056015 IPAJA NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 31 0 0 0 0 0 31 5636 056893 IPAJA CENTRAL NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 14 0 0 0 0 0 14 5636 060343 LAGOS ALAGBADO NIGERIA 404 B1 7 05-2015 16 2 0 0 -2 0 16 5636 061362 IBADAN METROPOLITAN NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 22 2 1 0 -7 -4 18 5636 061648 NEW FESTAC NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 48 11 1 0 -4 8 56 5636 061939 AGEGE NIGERIA 404 B1 4 05-2015 21 5 0 0 -3 2 23 5636 062313 LAGOS AKOWONJO NIGERIA 404 B1 4 04-2015 49 3 0 0 -2 1 50 5636 062660 DOPEMU NIGERIA 404 B1 4 06-2014 17 0 0 0 0 0 17 5636 062769 AJAO ESTATE NIGERIA 404 B1 4 04-2015 -

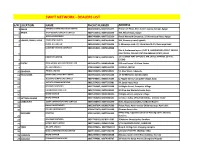

Dealers List

SWIFT NETWORK - DEALERS LIST S/N LOCATION NAME PHONE NUMBER ADDRESS 1 AGEGE FOAMAD COMMUNICATION LIMITED 08023225876, 08077265677 Primal Tek Plaza, Blk C Suite 5 opp Iju Garage, Agege 2 APAPA VYOP GLOBAL CONCEPTS LIMITED 08034136372, 08077265250 300, Wharf Road, Apapa 3 RITECH ENTERPRISES 08067409084, 08077265250 Ritech Network Enterprise, 25 Warehouse Road, Apapa 4 EGBEDA, IDIMU, IPAJA FIBREPATH LIMITED 08037919818, 08074648599 205, Akowonjo road, Egbeda 5 PHONE 4 U LIMITED 08050696043, 08077265226 9, Akowonjo road; 27, Idimu Road & 39, New Ipaja Road. SONSHINE SYSTEMS COMPANY 08034958191, 08074648808 Plot 8, Anifowose layout ,PLOT 8, ANIFOWOSE LAYOUT, BESIDE 6 FIRST ROYAL FILLING STATION ABESAN ESTATE, IPAJA FIBREPATH LIMITED 08037919818, 08074539974 20, OLUADE WAY OPPOSITE MR. BIGGS JAKANDE ESTATE, 7 EJIGBO 8 FESTAC IDEAL MOBILE AND ELECTRONICS LTD 08126865776, 08063045009 512 road house 1 B Close, festac. 9 YES SUPERMARKET 07081625689, 08095463739 21 ROAD, FESTAC 10 GBAGADA PHOLEX LIMITED 08023204256, 08074648621 57, Diya Street, Gbagada 11 IKEJA/OGBA GREAT BAKIS VENTURES LIMITED 08099500028, 08077260143 13 ISHERI ROAD AGUDA OGBA 12 BLESSING COMPUTERS LIMITED 08074648057, 08033576109 5, Pepple Street, Computer Village, Ikeja 13 VICINITY COMMUNICATIONS 08023274269, 08077265981 54, Opebi road, Ikeja 14 BIDLANDS VENTURES 08077265981, 08052321139 14 Otigba Street, Computer Village 15 TRENDWOLRD WIDE LTD 08027672448, 08074648132 82 Allen Ave Wuruola House Ikeja 16 MICRO STATION 08035374590, 08111386111, 9 Otigba street, computer village 17 VICTORIA ISLAND MICRO STATION 08077265250, 08078038181 11 Saka Tinubu, off Adeola Odeku, Victoria Island 18 LEKKI/AJAH ZEBRA COMMUNICATIONS SERVICES 08069388700, 08077265250 Ikota Shopping Complex, K198/133 Road 5 19 EMNAC INVESTMENTS 08033087194, 08108670296 Praise Plaza, Addo road by Skido bus stop, Ajah Lekki 20 EBEANO SUPERMARKET 07035677670, 08077265250 Chevron Drive Lekki SURULERE COMPSSA 07034164223, 08077266150 RM01 Shop, Opposite School Of Nursing LUTH, Idiaraba, 21 Surulere. -

(2017) Abstract of Local Government Statistics

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT ABSTRACT OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT STATISTICS 2017 LAGOS BUREAU OF STATISTICS MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING AND BUDGET, SECRETARIAT, ALAUSA, IKEJA. PREFACE The Abstract of Local Government Statistics is a yearly publication produced by the Lagos Bureau of Statistics (LBS). This edition contains detailed information on Y2016 Socio Economic Statistics of the 57 Local Government and Local Council Development Areas (LG/LCDAs) in Lagos State. The activities of the LG\LCDAS are classified into ten (10) components, these are: demographic distributions and nine (9) Classifications of functions of Government (COFOG). This publication is useful to all and sundry both locally and internationally for researchers, planners, private organizations and Non Governmental Organizations to mention but a few. The State wishes to express its appreciation to the officials of the Local Government and Local Council Development Areas (LG/LCDAs) and all Agencies that contributed to the success of the publication for their responses to the data request. The Bureau would be grateful to receive contributions and recommendations from concerned bodies and individuals as a form of feedback that will add values and also enrich subsequent editions. LAGOS BUREAU OF STATISTICS MINISTRY OF ECONOMIC PLANNING AND BUDGET BLOCK 19, THE SECRETARIAT, ALAUSA, IKEJA, LAGOS. Email: [email protected], [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE PAGE PREFACE DEMOGRAPHY 1.1 Area of land mass/water area of the old Twenty Local Government 1 Structure in Lagos State. 1.2 Population by sex according to Local Government Area in Lagos State: 2 2006 1.3 Local Government Area by Population Density 2006 3 1.4 Population Projections of the Local Government Area and their 4 Respective Population Density 2006, 2011‐2017 MANPOWER DISTRIBUTION 2.1 Manpower Distribution by Profession and Gender According 5‐6 to Local Government/Local Council Development Areas: Year 2016. -

Bankruptcy Forms

Case 18-32106 Document 186 Filed in TXSB on 06/07/18 Page 1 of 64 Fill in this information to identify the case: Debtor name Erin Petroleum Nigeria Limited United States Bankruptcy Court for the: SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS Case number (if known) 18-32109 Check if this is an amended filing Official Form 206A/B Schedule A/B: Assets - Real and Personal Property 12/15 Disclose all property, real and personal, which the debtor owns or in which the debtor has any other legal, equitable, or future interest. Include all property in which the debtor holds rights and powers exercisable for the debtor's own benefit. Also include assets and properties which have no book value, such as fully depreciated assets or assets that were not capitalized. In Schedule A/B, list any executory contracts or unexpired leases. Also list them on Schedule G: Executory Contracts and Unexpired Leases (Official Form 206G). Be as complete and accurate as possible. If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. At the top of any pages added, write the debtor’s name and case number (if known). Also identify the form and line number to which the additional information applies. If an additional sheet is attached, include the amounts from the attachment in the total for the pertinent part. For Part 1 through Part 11, list each asset under the appropriate category or attach separate supporting schedules, such as a fixed asset schedule or depreciation schedule, that gives the details for each asset in a particular category. -

16 Patigi 188Km 3 Hrs. 30 Mins

2 Barr. Augustine Obiekwe NSCDC State Commandant 08033142321 3 Mr. Segun Oke NDLEA State Commandant 08037236856 4 Mr. Tanimu Adal-khali SSS State Director 08033111017 5 Mrs. Mary Wakawa FRSC State Head of FRSC 08034957021 6 Brig. General A. A. Nani Nigerian Army Commander, 22 Ar. Brigade 08033148981 7 AVM S. N. Kudu Air force Com’der, Med. Airlift Group 08035881173 8 Mr. Peter O. Aburime Immigration State Comptroller 08037257292 9 Mr. Ayokanmbi A. O. Prison Service Controller 08160598454 10 Dr Emmanuel Onucheyo INEC REC 08062220080 DISTANCE OF LGA FROM STATE CAPITAL S/N LGA DISTANCE TIME 1 Asa 45km 50 Mins. 2 Baruten 243km 5 Hrs. 3 Edu 140km 2 Hrs. 30 Mins. 4 Ekiti 95km 2 Hrs. 5 Ifelodun 68km 1 Hr 20 Mins. 6 Ilorin East 6km 30 Mins. 7 Ilorin South 50km 1 Hr. 8 Ilorin West 5km 15 Mins. 9 Irepodun 84km 1 Hrs 15 Mins 10 Isin 75km 1 Hrs 30 Mins. 11 Kaiama 195km 5 Hrs. 12 Moro 87km 1 Hr 45 Mins. 13 Offa 65km 1 Hr 45 Mins. 14 Oke-Ero 88km 1 Hr 50 Mins. 15 Oyun 80km 2 Hrs. 16 Patigi 188km 3 Hrs. 30 Mins. LAGOS BRIEF HISTORY Lagos State was created on May 27th, 1976 with the capital at Ikeja. The state has a total area of 3,577km2 (1,38159ml), with a total population of 9,019,534 in the 2006 census figure. The state is located in the south-western part of Nigeria. It is bounded on the northward and eastward sides by Ogun State, shares boundaries with the Republic of Benin on its westward side, while the Atlantic Ocean lies on its southern side. -

Intimate Partner Violence Among Women of Child Bearing Age in Alimosho LGA of Lagos State, Nigeria

www.ajbrui.net Afr. J. Biomed. Res.Vol.18 (May, 2015); 135 - 146 Full Length Research Paper Intimate Partner Violence among Women of Child Bearing Age in Alimosho LGA of Lagos State, Nigeria Adegbite O.B and Ajuwon A.J* Department of Health Promotion & Education, University of Ibadan, Nigeria ABSTRACT In this study, the extent to which married women had experienced physical, sexual, psychological and economic forms of violence by their intimate partners was determined. The study was descriptive and cross-sectional. It was conducted in Alimosho Local Government Area (LGA) of Lagos State. Data were collected using a pre-tested, semi-structured, interviewer-assisted questionnaire from married women. The questionnaire explored demographic characteristics, experience of physical, sexual, psychological and economic forms of violence from their spouses, the perceived reasons for these acts and their health seeking behaviour. The respondents were selected through a systematic random technique from all the eight districts of the LGA. Of the 704 women contacted, 606 consented to participate in the study (response rate 86%). The ages of women ranged from 22 – 49 years with a mean of 35.9years (±6.48). Majority of the respondents were Yoruba 452 (74.6%) whose main occupation was trading 309 (51%). One hundred and sixty-one (26.6%) had secondary school education. Five hundred and thirty-nine (88.9%) had experience at least one form of violence. The prevalence of physical, sexual, psychological and economic forms of violence were 45.9%, 55.9%, 71.1% and 51.2% respectively. The most common forms of violent behaviours experienced by the women were slaps (41.9%), insistence on having sex (33.3%), verbal insults (41.3%) and not providing money for the needs of the family (38.4%). -

ICT) Use As a Predictor of Lawyers’ Productivity

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 11-2011 Information Communication Techonology (ICT) Use as a Predictor of Lawyers’ Productivity J.E. Owoeye University of Lagos, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Owoeye, J.E., "Information Communication Techonology (ICT) Use as a Predictor of Lawyers’ Productivity" (2011). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 662. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/662 http://unllib.unl.edu/LPP/ Library Philosophy and Practice 2011 ISSN 1522-0222 Information Communication Techonology (ICT) Use as a Predictor of Lawyers’ Productivity Jide Owoeye Principal Librarian Nigerian Institute of Advanced Legal Studies Lagos, Nigeria Introduction Information Communication Technology (ICT) is an umbrella term that includes all technologies for the manipulation and communication of information. The work of legal practitioners involves a high level of documentation and information processing, storage, and retrieval. The information intensiveness of a lawyer’s responsibility is such that tools and technologies that would speed up the documentation, management and information handling are not only important but professionally necessary. The value of accuracy, correctness, completeness, relevance and timeliness are characteristics of information which ICT systems do generate to meet lawyer’s information needs. The role of lawyers in any society is essential. In the early days, before the coming of the Europeans, each community in Nigeria had its own system of rules and practices regulating human behaviour. These were undocumented but known to all. Penalties which ranged from ostracism, payment of fines, and community service with close monitoring. -

Class Licence Register Telecenter/Cybercafé Category

CLASS LICENCE REGISTER TELECENTER/CYBERCAFÉ CATEGORY S/N COMPANY NAME ADDRESS LICENSE NUMBER 1 CVS Contracting International Ltd Suite 16B, Sabondale Shopping Complex, Jabi, Abuja CL/CYB/001/07 2 CHYSAN Communications & Books Ltd Suite 19, Oadis Plaza, CMD Road, Ikosi GRA, Ikosi‐Ketu, Lagos CL/CYB/002/07 3 GIDSON Investment Ltd 67, Gado Nasko Road, Kubwa, Abuja CL/CYB/003/07 4 Virtual Impact Company Ltd NO. 12, Eric Moore Road, Surulere, Lagos CL/CYB/004/07 5 Multicellular Business Links Ltd 91, Ijegun Road, Ikotun, Lagos CL/CYB/005/07 6 LAFAL (NIG) Enterprises Ltd 25, Idumu Road, Ikotun, Lagos CL/CYB/006/07 7 DATASTRUCT International Ltd No. 2, Chime Avenue, New Haven, Enugu CL/CYB/007/07 8 SADMART Internet Café & Business Center Shops 9 & 10, Kaltume House, Maiduguri Road, Kano State CL/CYB/008/07 9 PRADMARK Ltd No. 7, Moronfolu Street, Akoka‐Yaba, Lagos CL/CYB/009/07 10 WABLAM Enterprises 17, Oriwu Road, Ikorodu, Lagos CL/CYB/010/07 11 FETSAS Cyber Café 10, Isolo Rpad, Ijegun, Lagos CL/CYB/011/07 12 JARRED Communications Ltd Plot 450, 5th Avenue, Gowon Estate, Egbeda, Lagos CL/CYB/012/07 13 LEETDA Int'l Nigeria Ltd 2nd & 3rd Floor, 58, Herbert Macaulay Way, Ebute‐Metta, Lagos CL/CYB/013/07 14 JINI Ventures 1, Yomi Ishola Street, Off Ailegun Road, Ejigbo, Lagos CL/CYB/014/07 15 FALMUR Communications Nigeria Ltd 34, NBC Road, Ebute‐Ipakodo, Ikorodu, Lagos CL/CYB/015/07 1 16 KJS Consulting & Trade Ltd 22, Ewenla Street, Iyana‐Oworo, Bariga, Lagos CL/CYB/016/07 17 Network Excel Company Ltd 62, Akowonjo Road, Shop 13 & 14, Summit Guest House Complex, Egbeda, Lagos CL/CYB/017/07 18 SHEDDY Communications 25B, Irone Avenue, Aguda, Surulere, Lagos CL/CYB/018/07 19 Leader Tech Communications Ltd 7, Gbogan Road, Oshogbo, Osun State CL/CYB/019/07 20 MAGBUS Ventures 1, Owolabi Rabiu Close, Off Isawo Road, Agric, Owutu, Ikorodu, Lagos CL/CYB/020/07 21 Netwrok Packet Standard Co. -

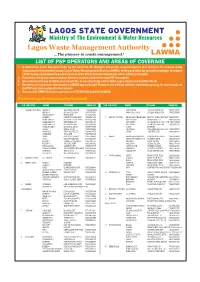

List of Psp Operators and Areas of Coverage 1

LAGOS STATE GOVERNMENT Ministry of The Environment & Water Resources Lagos Waste Management Authority ...The pioneer in waste management! LAWMA LIST OF PSP OPERATORS AND AREAS OF COVERAGE 1. In furtherance of the Executive Order by the Governor, Mr. Babajide Sanwo-Olu, on government's zero tolerance for reckless waste disposal and environmental abuse, Lagos Waste Management Authority (LAWMA), hereby publishes for general knowledge, the names of PSP operators mandated to provide services in the 20 Local Government Areas and 37 LCDAs in the state. 2. Remember to bag your wastes and put them in covered containers for easy PSP evacuation. 3. Also endeavour to pay promptly your waste bills, as we collectively work to make Lagos cleaner and healthier for all. 4. Residents are enjoined to download the LAWMA app on Google Playstore and visit our website, www.lawma.gov.ng, for more details on the PSP operators assigned to their streets. 5. You can call LAWMA for back up services on 07080601020 and 08034242660. #ForAGreaterLagos #KeepLagosClean #PayYourWastebill S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO S/N LGA/LCDA WARDS PSP NAME PHONE NO 1 AGBADO OKE ODO ABORU I GOFERMC NIG LTD "08038498764 OMITUNTUN IYALAJE WASTE CO. "08073171697 ABORU II MOJAK GOLD ENT "08037163824 SANTOS/ILUPEJU GOLDEN RISEN SUN "08052323909 ABULE EGBA II FUMAB ENT "08164147462 AGBADO CHRISTOCLEAR VENT "08058461400 7 AMUWO ODOFIN ABULE ADO/TRADE FAIR NEXT TO GODLINESS ENT "08033079011 AGBELEKALE I ULTIMATE STEVE VENT "08185827493 ADO FESTAC DOMOK NIG LTD "08053939988 AGBELEKALE II KHARZIBAB ENT "08037056184 EKO AKETE OLUWASEUN INV. COY LTD "08037139327 AGBELEKALE III METROPOLITAN "08153000880 IFELODUN GLORIOUS RISE ENT "08055263195 AGBULE EGBA I WOTLEE & SONS "08087718998 ILADO RIVERINE AJASA BOIISE TRUST "08023306676 IREPODUN CARLYDINE INV. -

The Ambassadors Schools, Ota

THE AMBASSADORS SCHOOLS, OTA This is to appreciate all schools that participated in TUMA 2018 Stage 1. We sincerely hope that your pupils had a delightful experience. The results have now been released and can be viewed below. Please note that the Top Twenty (20) Pupils from stage 1 have ‘QUALIFIED’ for the 2nd Stage. Further details will be communicated to them shortly. Also be informed that the school winners of the top performing school winners (50% score and above from Stage 1) alongside their teachers and parents are hereby invited for the award ceremony holding on Saturday 10th February, 2018, to receive their gifts and awards. Once again, congratulations to all and thank you for participating. THE AMBASSADORS SCHOOLS, OTA TUMA 2018 Result Sheet SCORES EXAM. S/N NAME OF STUDENT NAME OF SCHOOL SEX REMARKS NO SECTION SECTION SECTION TOTAL A (60) B (30) C (10) (100) 1 Oganla Faizal Oluwatobi Tomobid School, Ikeja Male 0886 55.5 21 10 86.5 TOP 20 (Qualified for Stage 2) 2 Adekanmbi Mofolusayo Oluwademilade Meadow Hall School, Lekki Female 0492 51 24 10 85 TOP 20 (Qualified for Stage 2) 3 Alonge Renfred Ize Scholars Universal Primary School, Iyana-Iyesi Ota Male 0636 49.5 27 8 84.5 TOP 20 (Qualified for Stage 2) 4 Akhabue Ebanehita Emmanuella The Frontliners Schools, Shasha Female 0634 49.5 24 10 83.5 TOP 20 (Qualified for Stage 2) 5 Ogunkoya Ayomikun David Advanced Breed Nursery and Primary School, Sagamu Male 0223 54 18 10 82 TOP 20 (Qualified for Stage 2) 6 Gbeja Karis Erioluwa Dr Soyemi Memorial Nursery and Primary School, Festac Town Female 0194 51 21 10 82 TOP 20 (Qualified for Stage 2) 7 Akinyemi Jeremiah Best M&M Private School, Atakpa Ipaja Male 0830 51 21 10 82 TOP 20 (Qualified for Stage 2) 8 Obajimi Oluwanifemi Adebayo St. -

Registered Pharmacies on Hello Assur Network

REGISTERED PHARMACIES ON HELLO ASSUR NETWORK S/N STATE LGA LCDA NAME OF PHARMACY ADDRESS 1 LAGOS AGEGE LGA TEGLO PHARMACY 251, IJU ROAD, AGEGE 2 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA AYOBO/IPAJA LCDA EPSILON PHARMACY 50DF STREET, SHAGARI ESTATE, IPAJA 3 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA AYOBO/IPAJA LCDA ETHANIM PHARMACY 41,COMMAND ROAD, AJASA 4 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA AYOBO/IPAJA LCDA MASCOT PHARMACY 1 MONILARI CLOSE, CHURCH STREET, ABESAN, IPAJA 5 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA AYOBO/IPAJA LCDA TRUSTEDCARE PHARMACY & STORES LTD MAJOR BUS STOP, ALONG ALAJA-OLAYEMI ROAD, MEGIDA, AYOBO 6 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA AYOBO/IPAJA LCDA VINA PHARMACEUTICAL LIMITED 51, CAPTAIN DAVIES ROAD, AYOBO 7 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA EJIGBO LCDA HAROSE PHARMACEUTICALS LTD 21, IDIMU-EJIGBO ROAD, IDIMU 8 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA EJIGBO LCDA HEALTHMAPS PHARMACY LTD NO 1 ADEKUNJO ST OPP SYNAGOGUE CHURCH IKOTUN LAGOS 9 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA MOSAN/ OKUNOLA LCDA CLICH PHARMACY 3 GORDILOVE STREET, AKOWONJO. 10 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA MOSAN/ OKUNOLA LCDA DRUGGMIX CARE LIMITED 1,TIWATAYO STREET, UNITY ESTATE, EGBEDA 11 LAGOS ALIMOSHO LGA MOSAN/ OKUNOLA LCDA SALVICH PHARMACY NO 9 LAWAL STREET, AKOWONJO, EGBEDA. 12 LAGOS AMUWO ODOFIN LGA AVANT GROBEL PHARMACY FIRST AVENUE, BY 11 ROAD JUNCTION, FESTAC TOWN 13 LAGOS AMUWO ODOFIN LGA AVANT GROBEL PHARMACY PLOT 1901, BLOCK XV, PHASE 11, FESTIVAL TOWN, ABULE-ADO 14 LAGOS AMUWO ODOFIN LGA AVANT GROBEL PHARMACY 21, IREDE RD, ABULE-OSHUN, OPP TRADEFAIR COMPLEX, BADAGRY EXP WAY 15 LAGOS AMUWO ODOFIN LGA FRANPAT PHARMACY LIMITED 21/31ROAD FESTAC TOWN LAGOS 16 LAGOS AMUWO ODOFIN LGA VICTORY DRUGS 11 ROAD FESTAC TOWN 17 LAGOS ETI-OSA LGA IRU/VI LCDA DR.