Redefining Quaker Simplicity: the Friends Committee on National Legislation Building, 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Becoming and Remaining Vegetarian

Wang, Yahong (2020) Vegetarians in modern Beijing: food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/77857/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Vegetarians in modern Beijing: Food, identity and body techniques in everyday experience Yahong Wang B.A., M.A. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Social and Political Sciences College of Social Sciences University of Glasgow March 2019 1 Abstract This study investigates how self-defined vegetarians in modern Beijing construct their identity through everyday experience in the hope that it may contribute to a better understanding of the development of individuality and self-identity in Chinese society in a post-traditional order, and also contribute to understanding the development of the vegetarian movement in a non-‘Western’ context. It is perhaps the first scholarly attempt to study the vegetarian community in China that does not treat it as an Oriental phenomenon isolated from any outside influence. -

In Fox's Footsteps: Planning 1652 Country Quaker Pilgrimages 2019

in fox's footsteps: planning 1652 country quaker pilgrimages 2019 Why come “If you are new to Quakerism, there can be no on a better place to begin to explore what it may mean Quaker for us than the place in which it began. pilgrimage? Go to the beautiful Meeting Houses one finds dotted throughout the Westmorland and Cumbrian countryside and spend time in them, soaking in the atmosphere of peace and calm, and you will feel refreshed. Worship with Quakers there and you may begin to feel changed by the experience. What you will find is a place where people took the demands of faith seriously and were transformed by the experience. In letting themselves be changed, they helped make possible some of the great changes that happened to the world between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries.” Roy Stephenson, extracts from ‘1652 Country: a land steeped in our faith’, The Friend, 8 October 2010. 2 Swarthmoor Hall organises two 5 day pilgrimages every year Being part of in June/July and August/September which are open to an organised individuals, couples, or groups of Friends. ‘open’ The pilgrimages visit most of the early Quaker sites and allow pilgrimage individuals to become part of an organised pilgrimage and worshipping group as the journey unfolds. A minibus is used to travel to the different sites. Each group has an experienced Pilgrimage Leader. These pilgrimages are full board in ensuite accommodation. Hall Swarthmoor Many Meetings and smaller groups choose to arrange their Planning own pilgrimage with the support of the pilgrimage your own coordination provided by Swarthmoor Hall, on behalf of Britain Yearly Meeting. -

A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 6-11-2009 A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau Jack Turner University of Washington Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Turner, Jack, "A Political Companion to Henry David Thoreau" (2009). Literature in English, North America. 70. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/70 A Political Companion to Henr y David Thoreau POLITIcaL COMpaNIONS TO GREat AMERIcaN AUthORS Series Editor: Patrick J. Deneen, Georgetown University The Political Companions to Great American Authors series illuminates the complex political thought of the nation’s most celebrated writers from the founding era to the present. The goals of the series are to demonstrate how American political thought is understood and represented by great Ameri- can writers and to describe how our polity’s understanding of fundamental principles such as democracy, equality, freedom, toleration, and fraternity has been influenced by these canonical authors. The series features a broad spectrum of political theorists, philoso- phers, and literary critics and scholars whose work examines classic authors and seeks to explain their continuing influence on American political, social, intellectual, and cultural life. This series reappraises esteemed American authors and evaluates their writings as lasting works of art that continue to inform and guide the American democratic experiment. -

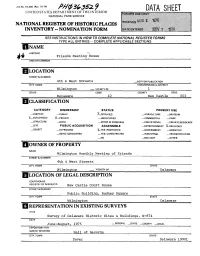

Nomination Form

jrm No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) />#$ 36352.9 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Friends Meeting House AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREETS NUMBER 4th & West Streets -NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Wilmington VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Delaware 10 New Castle 002 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC ^-OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X—BUILDING(S) X.-PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE __BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT X_RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED __YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO .-MILITARY —OTHER: (OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Wilmington Monthly Meeting of Friends STREET & NUMBER 4th & West Streets CITY. TOWN STATE Wilmington VICINITY OF Delaware LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. New Castle Court House STREET & NUMBER Public Building, Rodney Square CITY, TOWN STATE Wilmington Delaware 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Survey of Delaware Historic Sites & Buildings, N-874 DATE June-August, 1975 —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Hall of Records CITY, TOWN STATE Dover Delaware 19901 DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^-EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X_ORIGINALSITE —GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE_ —FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Friends Meeting House, majestically situated on Quaker Hill, was built between 1815 and 1817 and has changed little since it was built. What change has occurred has not altered the integrity of the building. -

Quaker Thought and Life Today

Quaker Thought and Life Today JUNE 1, 1964 NUMBER 11 .. Quakerism and Creed by Alfred S. Roberts, Jr. f!l, U A.KERISM cannot The Pursuit of Truth in a Quaker prove that there is that of God in every man; it can only College say that when men behave as by Homer D. Babbidge, Jr. though there were, the weight of evidence amply justifies the belief. It cannot prove that love will solve all problems; it can only note that love has The Civil Rights Revolution a much better record than by John De J. Pemberton, Jr. hate. -CARL F. WISE The Little Ones Shall Lead Them by Stanley C. Marshall THIRTY CENTS $5.00 A YEAR ' ' Letter from Costa Rica-Letter from the Past . • 242 FRIENDS JOURNAL June 1, 1964 FRIENDS JOURNAL UNDER THE RED AND BLACK STAR AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Lucky Money *HE newest project of the AFSC's Children's Program T is the Happiness Holiday Kit, which gives basic in formation about the Committee's Hong Kong day nurs ery. The Kit contains, along with other materials, bright red and gold envelopes for "Lucky Money" to assist the Published semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each month, at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Quakers in their work with Hong Kong children and 19102, by Friends Publlshlng Corporation (LO 3-7669). mothers. This project, launched in the fall of 1963, al FRANCES WILLIAMS BROWIN Editor ready has brought in more than $3000 for the AFSC's ETHAN A. NEVIN WILLIAM HUBBEN Assistant Editor Contributing Editor work in Hong Kong. -

Column1 Column2 Column3 Column4 Column5 Column6 Column7 Column8 Column9 Column10 Column11 AUTHOR TITLE CALL PUBLISHER City PUB

Column1 Column2 Column3 Column4 Column5 Column6 Column7 Column8 Column9 Column10 Column11 AUTHOR TITLE CALL PUBLISHER City PUB. COPY# SUBJECT 1 SUBJECT 2 SUBJECT 3 NOTES NUMBER DATE Aarek, William From Loneliness to Fellowship: a Swarthmore George Allen London 1954 1 Quakerism, Psychology study in psychology and Lecture & Unwin Ltd. Introduction Quakerism Pamphlets Aarek, William From Loneliness to Fellowship: a Swarthmore George Allen London 1954 2 Quakerism, Psychology study in psychology and Lecture & Unwin Ltd. Introduction Quakerism Pamphlets Abbott, Margery Post Christianity and the Inner Life: PH #402 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 2009 1 Christianity - Twenty-First Century Reflections Spiritual Life on the Words of Early Friends Abbott, Margery Post To Be Broken and Tender: A 289.6 Western 2010 1 Quaker Quaker theology for today Ab2010to Friend Theology Abbott, Margery Post, Walk Worthy of Your Calling, 289.6 Friends Richmond, IN 2004 1 Pastoral Travel - Parsons, Peggy Quakers and the Traveling Ministry Ab2004wa United Press Theology - Religious Senger eds. Society of Aspects Friends Abbott, Margery Post; Historical Dictionary of Friends 289.6 Scarecrow Lanham, MD 2003 1 Society of Chijoke, Marry Ellen; (Quakers) Ab2003hi Press Friends - Dandelion, Pink; History - Oliver, John William Dictionary Abrams, Irwin To the Seeker Brochure Friends Philadelphia ND 1 Quakerism, General Introduction Conference Alexander, Horace Everyman's Struggle For Peace PH #74 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 1953 2 Pendle Hill Pamphlet Alexander, Horace G. Gandhi Remembered PH#165 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA 1969 1 Pendle Hill Gandhi, Pamphlet Mohandas - Non- violence Alexander, Horace G. Quakerism in India PH #31 Pendle Hill Wallingford, PA ND 1 Pendle Hill Pamphlet Alexander, Horace G. -

“What I'm Not Gonna Buy”: Algorithmic Culture Jamming And

‘What I’m not gonna buy’: Algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube Item Type Article Authors Wood, Rachel Citation Wood, R. (2020). ‘What I’m not gonna buy’: Algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube. New Media & Society. Publisher Sage Journals Journal New Media and Society Download date 30/09/2021 04:58:05 Item License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10034/623570 “What I’m not gonna buy”: algorithmic culture jamming and anti-consumer politics on YouTube ‘I feel like a lot of YouTubers hyperbolise all the time, they talk about how you need things, how important these products are for your life and all that stuff. So, I’m basically going to be talking about how much you don’t need things, and it’s the exact same thing that everyone else is doing, except I’m being extreme in the other way’. So states Kimberly Clark in her first ‘anti-haul’ video (2015), a YouTube vlog in which she lists beauty products that she is ‘not gonna buy’.i Since widely imitated by other beauty YouTube vloggers, the anti-haul vlog is a deliberate attempt to resist the celebration of beauty consumption in beauty ‘influencer’ social media culture. Anti- haul vloggers have much in common with other ethical or anti-consumer lifestyle experts (Meissner, 2019) and the growing ranks of online ‘environmental influencers’ (Heathman, 2019). These influencers play an important intermediary function, where complex ethical questions are broken down into manageable and rewarding tasks, projects or challenges (Haider, 2016: p.484; Joosse and Brydges, 2018: p.697). -

Kelly Rae Chi a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of North

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository THE MOTIVATIONS AND CHALLENGES OF LIVING SIMPLY IN A CONSUMING SOCIETY Kelly Rae Chi A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Professor Jan Johnson Yopp, adviser Professor Barbara Friedman, reader Professor Stephen Birdsall, reader ©2008 Kelly Rae Chi ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT KELLY R. CHI: The Motivations and Challenges of Living Simply in a Consuming Society (Under the direction of Jan Yopp, Barbara Friedman and Stephen Birdsall) Voluntary simplicity, a cultural movement that focuses on buying less and working less, blossomed in the mid-1990s as increasing numbers of Americans voiced dissatisfaction with excessive consumerism and working long hours. While the movement is not formalized today, many Americans do live simply, according to some of the simplicity literature. Practices range from buying only environmentally friendly products, following religious guidelines, or living in communal settings. Though the weakening U.S. economy makes simplicity an attractive or necessary way of life, the daily lives of simplifiers are underreported in the mainstream media. Since 2003, newspaper articles on simplicity have diminished, and existing articles lack context on the varied motivations and challenges of the simplicity movement and how some Americans live simply. This thesis and its series of articles aims to fill that gap by looking at simplicity research as well as the stories of local people in family and community settings. -

304 Arch Street the First Quaker

Price 5/- ($1.25) THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME TWENTY-SEVEN 1930 London THE FRIENDS' BOOK CENTRE EUSTON ROAD, N.W.I Philadelphia Pa. ANNA W. HUTCHINSON 304 Arch Street The First Quaker <£>encalogi>&*?*** nub History GEORGE FOX v SEEKER AND FRIEND SEARCHES UNDERTAKEN in the Records of the London By RUFUS M. JONES, LL j>. and County Probate The biography of the Founder Registries, Public Record of the Quaker movement, of whom William James said Office, British Museum, that ''everyone who con Society of Friends and fronted him personally from Oliver Cromwell down to other libraries, Parish county magistrates and Registers, etc. jailers, seemed to have acknowledged his superior powers/' MRS. CAFFALL, With Frontispiece ROUGH WALLS, PARK WAY, 5s. RUISLIP, MIDDLESEX, ENGLAND. GEORGE ALLEN & UNWIN LTD VALUABLE NEW SUPPLEMENTS (i6& 17) to this Journal PEN PICTURES of LONDON YEARLY MEETING, 1789-1833 Records and impressions by contemporary diarists, edited by NORMAN PENNEY, LL.D. Introduction by T. EDMUND HARVEY. Portraits; copious notes; index. From the Society, or booksellers, izs. 6d. ($3.25) post 6d., in two parts as issued. FRIENDS OF THE NEAR EAST By MARGARET SEFTON-JONES, F.R.Hisr.S. ILLUSTRATED IN LINE AND COLOUR BY EDITH HUGHES (8J x 6J, 60 pages) 2s. 6d- Postage id. Printed and Published by HEADLEY BROTHERS Printers of Memoirs, Reports and Books of all descriptions THE INVICTA PRESS, ASHFORD, KENT AND 18 DEVONSHIRE STREET, LONDON, E.C.z THE JOURNAL OF THE FRIENDS HISTORICAL SOCIETY EDITED BY NORMAN PENNEY, LL.D., F.S.A., F.R.HistS. -

On Speaking in Meetingfor Worship and Meeting

May 1996 Quaker Thought FRIENDS and Life OURNAL Today I! I I I / / On Speaking in Meetingfor Worship Love and Meeting Noise I \ - i 1\,, ,• Quakers on the ~b I I ' ' Among Friends Editor-Manager Vinton Deming Associate Editor Kenneth Sutton Alabama '96 Assistant Editor Timothy Drake ometimes a news article touches the heart and moves people to reach out to one Art Director another in unexpected ways. So it was this winter when the Washington Post Barbara Benton published a piece on the rash of fires that have destroyed black churches in the Production Assistant S Alia Podolsky South in recent months. There have been 23 reported fires in seven Southern states in Development Consultant the past three years, all of which were proven or suspected to be the work of Henry Freeman arsonists. Nineteen of the fires have occurred since January 1995. Marketing and Advertising Manager Nagendran Gulendran Last December's burning of the 100-year-old Mount Zion Baptist Church in Administrative Secretary Boligee, Alabama, was a total loss. Three weeks later, on January 11, two other Marie McGowan black churches in the same county were burned to the ground on the same night. On Bookkeeper February 1, four churches were torched in Louisiana, three in the town of Baker. No Nancy Siganuk arrests have been made in any of these most recent incidents. Poetry Editor Judith Brown When Friend Harold B. Confer, executive director of Washington Quaker Development Data Entry Workcamps, saw the article, he decided to do something about it. After a series of Pamela Nelson phone calls, he and two colleagues accepted an invitation to travel to western Intern Alabama and see the fire damage for themselves. -

MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 615 Montgomery Avenue Not for publication:_ City/Town: Merion Station Vicinity:_ State: PA County: Montgomery Code: 091 Zip Code: 19006 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): X Public-Local: _ District: _ Public-State: _ Site: _ Public-Federal: Structure: _ Object: _ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 _ buildings 1 _ sites _ structures _ objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 0 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 MERION FRIENDS MEETING HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Friends Meeting House, Brigflatts

Friends Meeting House, Brigflatts Brigflatts, Sedbergh, LA10 5HN National Grid Reference: SD 64089 91155 Statement of Significance Brigflatts has exceptional heritage significance as the earliest purpose-built meeting house in the north of England, retaining a richly fitted interior and an unspoilt rural setting. The vernacular building is Grade 1 listed, and important as a destination for visitors as well as a meeting house for Quaker worship. Evidential value The meeting house has high evidential value for its fabric which incorporates historic joinery and fittings of several phases, from the early eighteenth century through to the early 1900s, illustrating incremental repair and renewal. The burial ground and ancillary stable and croft buildings also have archaeological potential. Historical value The site is associated with a 1652 visit by George Fox to the area, and to the growth of Quakerism in this remote rural area. The meeting house was built in 1674-75 and fitted out over the following decades, according to Quaker requirements and simple taste. The burial ground has been in continuous use since 1656 and is the burial place of the poet Basil Bunting. The building and place has exceptional historical value. Aesthetic value The form and design of the building is typical of late seventeenth century vernacular architecture in this area, constructed in local materials and expressing Friends’ approach to worship. The attractive setting of the walled garden, paddock and outbuildings adds to its aesthetic significance. The exterior, interior spaces and historic fittings ad furnishings have exceptional aesthetic value. Communal value The meeting house is primarily a place for Quaker worship but is important to visitors to this western part of the Yorkshire Dales.