From Méliès to Galaxy Quest: the Dark Matter of the Popular Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter Arrives with a Wallop

weather Monday: Showers, high 42 degrees monday Tuesday: Partly cloudy, high 42 degrees Wednesday: Rain likely, high in the low 40s THE ARGO Thursday: Rain likely , high in the upper 30s Volume 58 Friday: Chance of rain , high in the low 30s of the Richard Stockton College Number 1 Serving the college community since 1973 m ihh Winter arrives with a wallop Dan G rote ed to engage in snowball fights The Argo despite or perhaps in spite of the decree handed down by the Much like the previous semes- Office of Housing and ter, when Hurricane Floyd barked Residential Life, which stated at Stockton, the new semester has that snowball fighters can expect begun with weather-related can- a one hundred dollar fine and loss cellations. In the past two weeks, of housing. four days of classes have seen One freshman, Bob Atkisson, cancellations, delayed openings, expressed his outrage at the and early closings. imposed rule. "I didn't think we Snowplows have crisscrossed should get fined for throwing the campus, attempting to keep snowballs. I went to LaSalle a the roads clear, while at the same couple days ago, and they actual- time blocking in the cars of resi- ly scheduled snowball fights dents, some of whom didn't real- there." ly seem to mind. Though many students were Optimistic students glued heard grumbling over having to themselves to channel 2 in hopes dig their cars out of the snow due of not having to go to their 8:30 to the plowing, they acknowl- classes, while others called the edged that plant management did campus hotline (extension 1776) an excellent job keeping for word of the same. -

The Human Adventure Is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: the Next Generation

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY HONORS CAPSTONE The Human Adventure is Just Beginning Visions of the Human Future in Star Trek: The Next Generation Christopher M. DiPrima Advisor: Patrick Thaddeus Jackson General University Honors, Spring 2010 Table of Contents Basic Information ........................................................................................................................2 Series.......................................................................................................................................2 Films .......................................................................................................................................2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................3 How to Interpret Star Trek ........................................................................................................ 10 What is Star Trek? ................................................................................................................. 10 The Electro-Treknetic Spectrum ............................................................................................ 11 Utopia Planitia ....................................................................................................................... 12 Future History ....................................................................................................................... 20 Political Theory .................................................................................................................... -

Never Surrender

AirSpace Season 3, Episode 12: Never Surrender Emily: We spent the first like 10 minutes of Galaxy Quest watching the movie being like, "Oh my God, that's the guy from the... That's that guy." Nick: Which one? Emily: The guy who plays Guy. Nick: Oh yeah, yeah. Guy, the guy named Guy. Matt: Sam Rockwell. Nick: Sam Rockwell. Matt: Yeah. Sam Rockwell has been in a ton of stuff. Emily: Sure. Apparently he's in a ton of stuff. Nick: Oh. And they actually based Guy's character on a real person who worked on Star Trek and played multiple roles and never had a name. And that actor's name is Guy. Emily: Stop. Is he really? Nick: 100 percent. Intro music in and under Nick: Page 1 of 8 Welcome to the final episode of AirSpace, season three from the Smithsonian's National Air and Space Museum. I'm Nick. Matt: I'm Matt. Emily: And I'm Emily. Matt: We started our episodes in 2020 with a series of movie minis and we're ending it kind of the same way, diving into one of the weirdest, funniest and most endearing fan films of all time, Galaxy Quest. Nick: The movie came out on December 25th, 1999, and was one of the first widely popular movies that spotlighted science fiction fans as heroes, unlike the documentary Trekkies, which had come out a few years earlier and had sort of derided Star Trek fans as weird and abnormal. Galaxy Quest is much more of a love note to that same fan base. -

SFA News Network Vol 1 Editor: Daniel Dreesbach Publisher

SFA News Network Vol 1 Editor: Daniel Dreesbach Publisher: Daniel Dreesbach Commandant’s READY ROOM DeForest Kelley/Dr. Leonard McCoy Medical Scholarship goes to Darlene Topp from USS Hadfield out of R#13. Congratulations James, Jennifer, Angel, and Darlene. Welcome to another issue of the Starfleet Academy newsletter. Thank you Daniel Dreesbach for putting this Every year the academy presents Squadron Awards to the issue together. Daniel has been made the Academy’s Chief best adult students (Red), cadet students (Blue), and family of the Alumni Association as well as the Editor of our of students (Gold). There were many and I have sent these newsletter. Congratulations and welcome, Daniel. on to be listed in CQ 148 along with the list of Boothby Award recipients. Congratulations to all...Awesome. Congratulations! Wayne Killough, Jr. on your promotion Students of our academy are not the only recipients of to Vice Admiral. awards. Each year some of our staff receives awards. They were chosen by their peers as well as the Most of you might know by now, but if not, please administration for the profound work they have welcome Reed Bates to our staff. Reed has taken on the accomplished through the year. I’m proud to announce and position of Scholarship Director. She has been worked congratulate the following: tirelessly in order to get the scholarship program underway and ready to accept applications. Even with the short Dean of the Year: Carolyn Donner, Institute of the Year: notice we did get four recipients of academy scholarships. Institute of Science Fiction Studies (Each director shares I am very proud to announce the names of the four this award. -

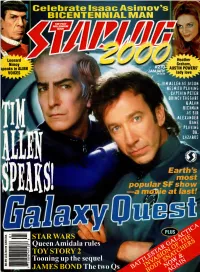

Starlog Magazine

Celebrate Isaac Asimov's BICENTENNIAL MAN 2 Leonard * V Heather Nimoy Graham, speaks in ALIEN — AUSTIN POWERS' VOICES lady love 1 40 (PIUS) £>v < -! STAR WARS CA J OO Queen Amidala rules o> O) CO TOY STORY 2 </) 3 O) Tooning up the sequel ft CD GO JAMES BOND The two Q THE TRUTH If you're a fantasy sci-fi fanatic, and if you're into toys, comics, collectibles, Manga and anime. if you love Star Wars, Star Trek, Buffy, Angel and the X-Files. Why aren't you here - WWW.ign.COtH mm INSIDE TOY STORY 2 The Pixarteam sends Buzz & Woody off on adventure GALAXY QUEST: THE FILM Questarians! That TV classic is finally a motion picture HEROES OF THE GALAXY Never surrender these pin- ups at the next Quest Con! METALLIC ATTRACTION Get to know Witlock, robot hero & Trouble Magnet ACCORDING TO TIM ALLEN He voices Buzz Lightyear & plays the Questarians' favorite commander THAT HEROIC GUY Brendan Fraser faces mum mies, monsters & monkeys QUEEN AMIDALA RULES Natalie Portman reigns against The Phantom Menace THE NEW JEDI ORDER Fantasist R.A. Salvatore chronicles the latest Star Wars MEMORABLE CHARACTER Now & Again, you've seen actor ! Cerrit Graham 76 THE SPY WHO SHAGS WELL Heather Graham updates readers STARLOC: The Science Fiction Universe is published monthly by STARLOG GROUP, INC., 475 Park Avenue South, New York, on her career moves NY 10016. STARLOG and The Science Fiction Universe are registered trademarks of Starlog Group Inc' (ISSN 0191-4626) (Canadian GST number: R-124704826) This is issue Number 270, January 2000. -

Alien Mystery Camp Planner

Camping Planner Alien Mystery Camp Theme Alien Movie Quiz© By Samantha Eagle © All Rights Reserved 2018 Copyright Notices © Copyright Samantha Eagle All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means mechanical or electronic, including photocopying and recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The purchaser is authorised to use any of the information in this publication for his or her own use ONLY. For example, if you are a leader trainer you are within your rights to show any or all of the material to other leaders within your possession. However, it is strictly prohibited to copy and share any of the materials with anyone. Requests for permission or further information should be addressed to Samantha Eagle, PO Box 245, La Manga Club Murcia, 30389, Spain. Published by Samantha Eagle PO Box 245, La Manga Club Murcia, 30389, Spain. Email: [email protected] Legal Notices While all attempts have been made to verify information provided in this publication, neither Author nor the Publisher assumes any responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretation of the subject matter given in this product. © All Rights Reserved 2018 EasierScouting.com Camping Planner Alien Mystery Camp Theme Alien Movie Quiz© Overview The group will gather round the camp and do an ‘Alien Movie Quiz’. If you have older groups they can do this on their own. For younger groups get them do this in teams of 2. Preparation Before Camp 1. Print enough copies of the quiz for each person or each team of two Materials Needed • Pen or pencil Preparation At Camp 1. -

Souvenir & Program Book (PDF)

THAT STATEMENT CONNECTS the modern Steam Punk Movement, The Jetsons, Metropolis, Disney's Tomorrowland, and the other items that we are celebrating this weekend. Some of those past futures were unpleasant: the Days of Future Past of the X-Men are a shadow of a future that the adult Kate Pryde wanted to avoid when she went back to the present day of the early 1980s. Others set goals and dreams; the original Star Trek gave us the dreams and goals of a bright and shiny future t h a t h a v e i n s p i r e d generations of scientists and engineers. Robert Heinlein took us to the Past through Tomorrow in his Future History series, and Asimov's Foundation built planet-wide cities and we collect these elements of the past for the future. We love the fashion of the Steampunk movement; and every year someone is still asking for their long-promised jet pack. We take the ancient myths of the past and reinterpret them for the present and the future, both proving and making them still relevant today. Science Fiction and Fantasy fandom is both nostalgic and forward-looking, and the whole contradictory nature is in this year's theme. Many of the years that previous generations of writers looked forward to happened years ago; 1984, 1999, 2001, even 2010. The assumptions of those time periods are perhaps out-of-date; technology and society have passed those stories by, but there are elements that still speak to us today. It is said that the Golden Age of Science Fiction is when you are 13. -

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 MAY 2015 MAY COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 May15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 4/9/2015 2:47:37 PM May15 Dark Horse Ad.indd 1 4/9/2015 2:52:02 PM BARB WIRE #1 WE STAND ON DARK HORSE COMICS GUARD #1 IMAGE COMICS FREE COUNTRY: A TALE OF THE CHILDREN’S CRUSADE HC DC COMICS THE TOMORROWS #1 ISLAND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS STAR TREK/ GREEN LANTERN #1 IDW PUBLISHING CYBORG #1 STAR WARS: DC COMICS LANDO #1 MARVEL COMICS May15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 4/9/2015 2:55:25 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS 1 Archie Vs. Sharknado One-Shot l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Mercury Heat #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC The Spire #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Art of Mouse Guard: 2005-2015 HC l BOOM! STUDIOS Will Eisner’s The Spirit #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Bob’s Burgers #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Invader Zim #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Nickelodeon Magazine #1 l PAPERCUTZ 1 Nickelodeon Magazine #2 l PAPERCUTZ The Book of Death #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC The Demon Prince of Momochi House Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA LLC Awkward SC/HC l YEN PRESS Final Fantasy Type-0 Side Story Volume 1: Reaper Icy Blade GN l YEN PRESS Grimm Fairy Tales: Robyn Hood Omnibus TP l ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS The Best of Mike S. Miller Art Book HC l ART BOOKS The Hirschfeld Century HC l ART BOOKS Malefic Time: Apocalypse Volume 1 HC l ART BOOKS The Black Bat Double Novel Volume 1 l PULP HEROES 2 Star Wars: Jedi Academy Volume 3: The Phantom Bully HC l STAR WARS YOUNG READERS MAGAZINES DC -

SF42 Festival Program

SOMERVILLE THEATRE SF42 February 2017 Dear Film Lover, Thank you for coming to the 42nd installment of our long love affair with film and science fiction. For 42 years we have gathered in darkened theatres and journeyed into space, through time and into worlds only our imaginations could conjure. Some folks would look at this and say we are avoiding reality. I would counter, just the opposite. The stories we tell in science fiction film are the stories of right now. They reflect our concerns, our fears, and our hopes. The films we show at BostonSciFi will later be seen in theatres, on Netflix and other places. We are on the cutting edge of reality. You will see all of that in this year’s Festival. Filmmakers from around the world have shared their stories. By doing so, we find ourselves more similar than different, closer than we think, and much closer than the political environment would lead us to believe. So please, sit back and enjoy the 2017 version of the Boston Science Fiction Film Festival. We’re pleased you could make it, and we hope we have presented a unique, entertaining Festival. Thank you. Garen Daly Festival Director Boston Science Fiction Film Festival Table of Contents Special Events 2 Monster Movies 2 Schedule subject to change. Festival Films 3 For up-to-the-minute information SF 42 Schedule 6 please visit us online at Short Film Programs 10 www.bostonscfi.com. 24-Hour Sci-fi Marathon 11 Acknowledgments Inside Back Cover BOSTON SCIENCE FICTION FILM FESTIVAL SF42 SF42 February 10-20 See pages 6-7 for complete schedule. -

SCHEDULE of EVENTS

55 YEAR MISSION LAS VEGAS 2021 - SCHEDULE of EVENTS WHERE’S WHAT? Roddenberry Stage: Brasilia 7, Main Theatre: Pavilion, Photo op pick-up: Miranda 1-4, Photo ops: Miranda 5-8, Quark’s: Brasilia 1-3, Secondary Theatre: Brasilia 4-6, Ten Forward Lounge: Tropical C-D, Original Bridge Set: Palma, Roddenberry Display: Tropical E-H, Lego Display: Tropical A-B COLOR SYSTEM: Red – Main Theatre Programming, Light Blue – Secondary Theatre, Dark Blue – Roddenberry Stage, Green – Autographs, Purple – Photo ops, Orange – VIP schedule, Maroon – Private meet & greets PLEASE MAKE SURE TO SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE A REPLACEMENT OR MAKE UP TIME IF YOU MISS YOUR PHOTO OP OR AUTOGRAPH. Celebrity preferences for Photo ops handout is available at registration Gold & Captain’s Chair pass holders – if you kept your packages from the postponed 2020 show, please visit the Ticket Booth, located at the far right front of the Vendors room to pick up your gift certificate. This schedule is subject to change. Our website will have the most up-to-date schedule. Schedule changes will be noted on the Updates handout, available at registration. REGISTRATION HOURS (ROTUNDA/MAIN ENTRANCE) TUESDAY, AUGUST 10 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS ROOM WILL BE OPEN TOO so you can get first crack at autograph and photo op tickets as well as merchandise! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, CAPTAIN’S CHAIR, COPPER OR GA FULL CONVENTION PACKAGE. -

Women at Warp Episode 154: Book Club - Star Trek: the Motion Picture

Women at Warp Episode 154: Book Club - Star Trek: The Motion Picture Jarrah: Hi, and welcome to Women at Warp: a Roddenberry Star Trek podcast. Join us on our continuing mission to explore intersectional diversity in infinite combinations. My name is Jarrah, thanks for tuning in. Today with me I have Sarah. Sarah: Hello. Jarrah: And I also have Sue. Sue: Hidee-ho neighborinos. Jarrah: And we are returning to our Star Trek book club. And before we get into our main topic, which is the infamous novelization of Star Trek: The Motion Picture by the one only Gene Roddenberry, we have a little bit of housekeeping to do first. First of all, mega mega thanks to our patrons on Patreon who make this show possible. If you would like to become a patron, you can do so for as little as a dollar a month, and you get awesome rewards from thanks on social media, to silly watch-along commentaries and other things that are we're planning that are in the works and very exciting. So stay tuned. But no exaggeration to say that this really is what keeps our show going, pays for our hosting, for equipment, general, you know, we produce things to give out at conventions, spread the word, things like that. So thank you so much for everyone who supports our show. You can also support us by leaving a rating or review on Apple podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. And we also have a Teepublic store with new designs based on our new banner art, plus logos, and some other non podcast specific Trek designs. -

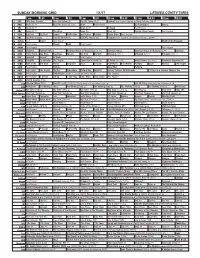

Sunday Morning Grid 1/1/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/1/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football New England Patriots at Miami Dolphins. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Paid Program Oz Reimagined Hockey 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Florida Citrus Parade Paid Program 9 KCAL Big Deal Big Deal People CHiP’s-Kids Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Dallas Cowboys at Philadelphia Eagles. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program March of the Penguins 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Downton Downton Abbey Downton Abbey on Masterpiece (8:37) Downton Abbey Downton Abbey on Masterpiece Å Downton 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Artbound (TVY) Å Artbound (TVY) Å Artbound (TVY) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Paid Program 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) Al Punto (N) (TVG) Netas Divinas (N) (TV14) República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Zona NBA Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog WordGirl Forever Painless With Miranda 21 Days to a Slimmer Younger You 52 KVEA Paid Program Fútbol Inglés Arsenal FC vs Crystal Palace FC.