The Relevance of Corporate Entrepreneurship in Share Price Performance: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Dividend Policy and Share Price Volatility”

“Dividend policy and share price volatility” Sew Eng Hooi AUTHORS Mohamed Albaity Ahmad Ibn Ibrahimy Sew Eng Hooi, Mohamed Albaity and Ahmad Ibn Ibrahimy (2015). Dividend ARTICLE INFO policy and share price volatility. Investment Management and Financial Innovations, 12(1-1), 226-234 RELEASED ON Tuesday, 07 April 2015 JOURNAL "Investment Management and Financial Innovations" FOUNDER LLC “Consulting Publishing Company “Business Perspectives” NUMBER OF REFERENCES NUMBER OF FIGURES NUMBER OF TABLES 0 0 0 © The author(s) 2021. This publication is an open access article. businessperspectives.org Investment Management and Financial Innovations, Volume 12, Issue 1, 2015 Sew Eng Hooi (Malaysia), Mohamed Albaity (Malaysia), Ahmad Ibn Ibrahimy (Malaysia) Dividend policy and share price volatility Abstract The objective of this study is to examine the relationship between dividend policy and share price volatility in the Malaysian market. A sample of 319 companies from Kuala Lumpur stock exchange were studied to find the relationship between stock price volatility and dividend policy instruments. Dividend yield and dividend payout were found to be negatively related to share price volatility and were statistically significant. Firm size and share price were negatively related. Positive and statistically significant relationships between earning volatility and long term debt to price volatility were identified as hypothesized. However, there was no significant relationship found between growth in assets and price volatility in the Malaysian market. Keywords: dividend policy, share price volatility, dividend yield, dividend payout. JEL Classification: G10, G12, G14. Introduction (Wang and Chang, 2011). However, difference in tax structures (Ho, 2003; Ince and Owers, 2012), growth Dividend policy is always one of the main factors and development (Bulan et al., 2007; Elsady et al., that an investor will focus on when determining 2012), governmental policies (Belke and Polleit, 2006) their investment strategy. -

Performance Update

Performance Update A Multi-Cap Value Fund Seeking Long-Term Capital Appreciation * Mark Boyar Overview of 2nd Quarter 2021 Mark began his career as a securities analyst in 1968. In 1975, he founded Asset Analysis Focus, a subscription-based, institutional Compared with the first quarter of 2021, when the Georgia Senate research service focused on value investing. He quickly began runoff elections secured Democratic control of Congress (via the vice- managing money for high net worth clients and later formed Boyar presidential tiebreaker), protestors descended on the Capitol Building, Asset Management, a registered investment advisor, in 1983. He began and Archegos Capital imploded, the second quarter of 2021 was managing the Boyar Value Fund in 1998. His opinions are often sought tranquil. This calmness was reflected in the stock market, with the by such media outlets as Barron’s, Business Week, CNBC, Forbes, VIX (a measure of stock market volatility) ending the first half of 2021 Financial World, the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal. at 15.8. (In March 2020, at the height of the pandemic, that level reached 82.7.) Top Ten Equity Holdings Will the calm in the markets continue? Not necessarily, according to Nicholas Colas, cofounder of DataTrek Research, who notes that Holdings during the summer months, when trading desks are thinly staffed, any surprising developments “hit the market harder than they otherwise might . and since volatility and returns have a negative correlation, this dynamic can make for difficult investment environments.” History bears this out, says Akane Otani, writing in the Wall Street Journal: July delivers average gains of 1.6%, but according to the Stock Traders Almanac, historical August returns have been so poor that “August's a good month to go on vacation: trading stocks will lead to frustration.” The S&P 500 finished the second quarter of 2021 selling for 21.5x earnings (fwd.) versus 19.2x at the February 19, 2020, pre-COVID peak and 13.3x at the March 23, 2020, pandemic low. -

The Copeland Review Second Quarter 2020

The Copeland Review Second Quarter 2020 “We believe that stocks with sustainable dividend growth consistently outperform the market with less risk. ” (Don’t) Press Your Luck! "Today, these three players are after Big Bucks, but they'll have to avoid the Whammy, as they play the most exciting game of their lives! Big bucks, big bucks, no Whammies, come on!” - Press Your Luck, 1980s, 2019 and ‘20 Game Show One quarter ago, both the S&P 500 Index and are frequently driven by the most impaired, As our country works through this the MSCI World Ex US Index were down -20% lowest quality, highest risk stocks. So far, this period, we would like to express our year-to-date, on a total return basis, while the category has done well, along with thematic continued appreciation of everyone on Nasdaq Composite Index was down -14%. biotech and technology stocks, many of the front lines dealing with COVID-19. Now, having staged a remarkable rebound, the which are not profitable. Going forward, we Our hearts truly go out to you as well S&P 500 Index finds itself down only -4% and believe dividend growers can use their finan- and to those individuals and families directly impacted by the virus. the MSCI World Ex US Index is off only- 10% as cial strength to win the next stage of recov- of the end of June. Even more incredible, the ery while also proving more resilient should Nasdaq Composite Index rallied into positive things go south again, especially considering territory and now stands up +13% as of June that the valuations of dividend growth stocks Chart 1. -

Creating an Ethical Stock Exchange

SKOLL CENTRE FOR SOCIAL ENTREPRENEURSHIP WORKING PAPER CREATING AN ETHICAL STOCK EXCHANGE JAMIE HARTZELL AUGUST 2007 2 CREATING AN ETHICAL STOCK EXCHANGE JAMIE HARTZELL 3 CONTENTS 5-13 SECTION 1 – WHY IS AN ETHICAL EXCHANGE NECESSARY? 22-26 SECTION 4 – THE STRUCTURE OF AN ETHICAL EXCHANGE 5 THE EXISTING MARKETS 22 THE STAKEHOLDERS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 PRICE SETTING ON THE EXISTING MARKETS 22 THE FUNCTIONS OF THE ETHICAL EXCHANGE 7 UNSUITABILITY OF THE EXISTING MARKETS FOR 22 TRADE AND NEW INVESTMENT EXECUTION ETHICAL BUSINESSES 22 COMPLIANCE WITH THE FINANCIAL SERVICES 8 THE EXTENT OF ETHICAL PUBLIC OFFERINGS (EPOS) AND MARKETS ACT AND THE COMPANIES ACT 10 DEMAND FOR AN ETHICAL EXCHANGE FROM 22 MARKETING SOCIAL ENTERPRISES 23 OWNERSHIP AND CONTROL OF THE EXCHANGE 11 THE BENEFITS OF A WIDE PUBLIC SHAREHOLDER BASE 23 ELIGIBLE INVESTMENTS CREATING A 12 DEMAND FOR AN ETHICAL EXCHANGE FROM INVESTORS 24 PRICING SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL RETURNS 25 CRITERIA FOR MARKET LISTING 14-17 SECTION 2 – THE EVOLUTION OF AN ETHICAL EXCHANGE 25 FINANCIAL CRITERIA 14 HISTORY OF ETHICAL SHARE TRADING TO DATE 25 SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL CRITERIA MARKET FOR 15 WHAT WOULD AN ETHICAL EXCHANGE DO? 25 TRANSPARENCY AND THE PROVISION 15 GENERATE LIQUIDITY IN INVESTMENTS IN OF INFORMATION SOCIAL ENTERPRISES 15 BRING NEW ISSUES TO MARKET 27-29 SECTION 5 – PRICING SHARES AND BONDS ETHICAL CAPITAL 15 ATTRACT NEW INVESTORS 27 THE FIVE MODELS 16 SUPPORT SMALLER ENTERPRISES WITH 27 OPTION 1 – FIXED PRICE TRADING START-UP FINANCE 27 OPTION 2 – SET PRICE TRADING 16 CREATE NEW -

The Stock Market and Investment: Is the Market a Sideshow?

RANDALL MORCK University of Alberta ANDREI SHLEIFER Harvard University ROBERT W. VISHNY University of Chicago The Stock Market and Investment: Is the Market a Sideshow? RECENT EVENTS and researchfindings increasingly suggest that the stock marketis not driven solely by news about fundamentals.There seem to be good theoreticalas well as empiricalreasons to believe that investor sentiment,also referredto as fads and fashions, affects stock prices. By investor sentimentwe mean beliefs held by some investors that cannot be rationallyjustified. Such investors are sometimesreferred to as noise traders. To affect prices, these less-than-rationalbeliefs have to be correlated across noise traders, otherwise trades based on mistaken judgments would cancel out. When investor sentiment affects the demandof enough investors, security prices diverge from fundamental values. The debates over marketefficiency, exciting as they are, would not be importantif the stock marketdid not affect real economic activity. If the stock marketwere a sideshow, marketinefficiencies would merely redistributewealth between smartinvestors and noise traders.But if the stock marketinfluences real economic activity, then the investor senti- ment that affects stock prices could also indirectlyaffect real activity. We would like to thankGene Fama, Jim Poterba,David Romer, Matt Shapiro,Chris Sims, and Larry Summersfor helpful comments. The National Science Foundation, The Centerfor the Study of the Economy and the State, the AlfredP. Sloan Foundation, and DimensionalFund Advisors providedfinancial support. 157 158 Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2:1990 It is well knownthat stock returnsby themselves achieve respectable R2 's in forecasting investment changes in aggregate data.' If stock returnsare infected by sentiment,and if stock returnspredict investment, then perhaps sentiment influences investment. -

The Complete Guide to Trading

The Corporate Finance Institute The Complete Guide to Trading The Complete Guide to Trading corporatefinanceinstitute.com 1 The Corporate Finance Institute The Complete Guide to Trading The Complete Guide to Trading (How to Trade the Markets and Win) A Publication of The Corporate Finance Institute corporatefinanceinstitute.com 2 The Corporate Finance Institute The Complete Guide to Trading “When you think the market can’t possibly go any higher (or lower), it almost invariably will, and whenever you think the market “must” go in one direction, nine times out of ten it will go in the opposite direction. Be forever skeptical of thinking that you know what the market is going to do.” – William Gallaher corporatefinanceinstitute.com 3 The Corporate Finance Institute The Complete Guide to Trading About Corporate Finance Institute® CFI is a world-leading provider of online financial analyst training programs. CFI’s courses, programs, and certifications have been delivered to tens of thousands of individuals around the world to help them become world-class financial analysts. The analyst certification program begins where business school ends to teach you job-based skills for corporate finance, investment banking, corporate development, treasury, financial planning and analysis (FP&A), and accounting. CFI courses have been designed to make the complex simple by distilling large amounts of information into an easy to follow format. Our training will give you the practical skills, templates, and tools necessary to advance your career and stand out from the competition. Our financial analyst training program is suitable for students of various professional backgrounds and is designed to teach you everything from the bottom up. -

Setting the Standard

Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commerical use See a sample reprint in PDF format only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, Order a reprint of this article now clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool on any article or visit www.djreprints.com FEATURE | SATURDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2010 Setting the Standard By MICHAEL SANTOLI The Barron's 400, based on stock-selection criteria that stress soundness and growth, has beaten most other major indexes since its inception. On the way: a tradable version. WITH HINDSIGHT, SEPTEMBER 2007 might not have been the most propitious time to launch a stock index based on strong individual-company fundamentals. A bear market worse than any in decades was about to strike—one in which global credit contagion and macroeconomic distress would swamp companies sound and dodgy alike. Yet the Barron's 400—unveiled three years ago and designed to beat the broad market with a disciplined selection process based on company growth and value factors—has fared well through the collapse and rebound. The index has handily outpaced the senior U.S. stock indexes since its inception. Through Thursday, it was down less than 15% since Aug. 31, 2007, compared with 24% for the Standard & Poor's 500 and 21% for the Dow Jones Industrial Average. Crucially, it also did better than the Dow Jones U.S. Total Stock Market index (off about 21%), from which the Barron's 400 components are picked. The B400 has somewhat trailed the S&P 400 Midcap index and the Nasdaq Composite, though it offers greater diversification than either in terms of sectors and company size. -

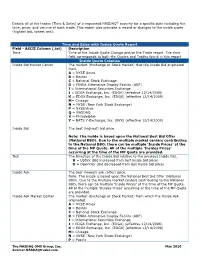

Details All of the Trades (Time & Sales) of a Requested NASDAQ® Security for a Specific Date Including the Time, Price

Details all of the trades (Time & Sales) of a requested NASDAQ® security for a specific date including the time, price, and volume of each trade. This report also provides a record of changes to the inside quote (highest bid, lowest ask). Time and Sales with Inside Quote Report Field - ASCII Column (.txt) Description Time Time of the Inside Quote Change and/or the Trade report. The time field corresponds to both the Quotes and Trades found in this report. Inside Quote Columns Inside Bid Market Center The market (Exchange or Stock Market) that the Inside Bid originated from. A = NYSE Amex B = Boston C = National Stock Exchnage D = FINRA Alternative Display Facility (ADF) I = International Securities Exchange J = EDGA Exchange, Inc. (EDGA) (effective 12/14/2009) K = EDGX Exchange, Inc. (EDGX) (effective 12/14/2009) M= Chicago N = NYSE (New York Stock Exchange) P = NYSE/Arca Q = NASDAQ X = Philadelphia Y = BATS Y-Exchange, Inc. (BYX) (effective 12/14/2009) Inside Bid The best (highest) bid price. Note: The inside is based upon the National Best Bid Offer (National BBO). Due to the multiple market centers contributing to the National BBO, there can be multiple 'Inside Prices' at the time of the MP Quote. All of the multiple 'Insides Prices' occurring at the time of the MP Quote are provided. Tick The Direction of the Inside Bid relative to the previous Inside Bid. U = Uptick (Bid increased from last inside bid price) D = Downtick (Bid decreased from last inside bid price) Inside Ask The best (lowest) ask (offer) price. Note: The inside is based upon the National Best Bid Offer (National BBO). -

Boyar Value Fund Semi-Annual Report – June 30, 2020

The Boyar Value Fund, Inc. BOYAX Semi-Annual Report June 30, 2020 Mutual Funds: • are not FDIC insured • have no bank guarantee • may lose value Beginning on January 1, 2021, as permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of the Fund’s shareholder reports like this one will no longer be sent by mail, unless you specifically request paper copies of the reports. Instead, the reports will be made available on the Fund’s website www.boyarassetmanagement.com, and you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted and provided with a website link to access the report. If you already elected to receive shareholder reports electronically, you will not be affected by this change and you need not take any action. You may elect to receive shareholder reports and other communications from the Fund electronically or to continue receiving paper copies of shareholder reports, which are available free of charge, by contacting your financial intermediary (such as a broker- dealer or bank) or, if you are a direct investor, by following the instructions included with paper Fund documents that have been mailed to you. 1 Our favorite holding period is forever. -- Warren Buffett Dear Boyar Value Fund Shareholder: Overview Boyar Asset Management (like most companies) continues to work remotely. Our investment in technology is paying dividends, as we were able to seamlessly transition to a remote environment, and it is business as usual. Our group is in constant contact, and our analyst team is working diligently to uncover equities that we can add to the portfolio and stress-testing existing positions. -

New York Stock Exchange Price List 2021

Price List 2021 New York Stock Exchange Price List 2021 Page 1 of 42 Price List 2021 Last Updated: September 24, 2021 Transaction Fees* Regular Session Trading1 Transactions in stocks with a per share stock price of $1.00 or more Non-Tier Adding Credit – Equity per Share Credit - per transaction - for all orders, other than Mid-Point Liquidity (“MPL”) and Non-Displayed Limit Orders that add liquidity to the NYSE unless a higher credit applies Members adding liquidity, excluding liquidity added as an Supplemental Liquidity Provider, in Tapes B and C Securities of at least 0.20% of Tape B and Tape C CADV combined will receive an additional $0.0001 per share. $0.0012 Adding Credit for Non-Displayed Limit Orders when adding liquidity to the NYSE unless a higher credit applies. No credit If the member organization has Adding ADV in Non-Displayed Limit Orders that is at least 0.12% of Tapes A, B and C CADV combined, excluding any liquidity added by a DMM. $0.0010 If the member organization has Adding ADV in Non-Displayed Limit Orders that is at least 0.15% of Tapes A, B and C CADV combined, excluding any liquidity added by a DMM. $0.0018 $0.0005 if an increase of at least 0.02% and less than 0.04% $0.0010 if an increase of at If the member organization has Adding ADV in Non-Displayed Limit least 0.04% and less than Orders and MPL Orders in Tapes A, B and C CADV combined, excluding any 0.08% liquidity added by a DMM, that is at least 0.02% of NYSE CADV over that member organization’s May 2020 adding liquidity in Non-Displayed Limit $0.0015 if an increase of at Orders and MPL Orders taken as a percentage of NYSE CADV. -

Marketplace Rules

MARKETPLACE RULES TABLE OF CONTENTS 4000. NASDAQ 4100. GENERAL 4110. Use of Nasdaq on a Test Basis 4120. Trading Halts IM-4120-1. Disclosure of Material Information IM-4120-2. Disclosure of Written Notice of Staff Determination 4200. DEFINITIONS 4200-1 DEFINITIONS IM - 4200 Definition of Independence - Rule 4200(a)(15) 4300. LISTING REQUIREMENTS FOR NASDAQ SECURITIES 4310. Listing Requirements for Domestic and Canadian Securities 4320. Listing Requirements for non-Canadian Foreign Securities and American Depositary Receipts 4330. Suspension or Delisting of a Security and Exceptions to Listing Criteria 4340. Reserved 4350. Qualitative Listing Requirements for Nasdaq National Market and Nasdaq SmallCap Market Issuers Except for Limited Partnerships 4350-1 Qualitative Listing Requirements for Nasdaq National Market and Nasdaq SmallCap Market Issuers Except for Limited Partnerships IM-4350-1. Interpretive Material Regarding Future Priced Securities IM-4350-2. Interpretative Material Regarding the Use of Share Caps to Comply with Rule 4350(i) IM-4350-3. Definition of a Public Offering IM-4350-4. Board Independence and Independent Committees Independent Directors and Independent Committees - Rule 4350(c) IM-4350-5. Shareholder Approval for Stock Option Plans or Other Equity Compensation Arrangements IM 4350-6. Applicability IM-4350-7. Code of Conduct 4351. Voting Rights IM-4351. Voting Rights Policy 4360. Qualitative Listing Requirements for Nasdaq Issuers That Are Limited Partnerships 1 4370. Additional Requirements for Nasdaq-Listed Securities Issued by Nasdaq or its Affiliates 4390. ISSUER DESIGNATION REQUIREMENTS IM-4390. Impact of Non-Designation of Dually Listed Securities 4400. NASDAQ NATIONAL MARKET 4410. Applications for Listing 4420. Quantitative Listing Criteria 4430. -

Relationship Between Interest Rate and Stock Price: Empirical Evidence from Developed and Developing Countries

International Journal of Business and Management (ISSN 1833-3850), Vol. 4(3), pp. 43-51, 2009 Relationship between Interest Rate and Stock Price: Empirical Evidence from Developed and Developing Countries Md. Mahmudul Alam Deputy Manager CRM, Marketing Division, Grameenphone Ltd. Dhaka, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Md. Gazi Salah Uddin Lecturer School of Business, Presidency University 11/A, Road-92, Gulshan-2 Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh E-mail: [email protected] Citation Reference: Alam, M.M., and Uddin, M.G.S. 2009. Relationship between Interest Rate and Stock Price: Empirical Evidence from Developed and Developing Countries, International Journal of Business and Management, Vol. 4(3), pp. 43-51. Available at <http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ijbm/article/download/217/177>. This is a pre-publication copy. The published article is copyrighted by the publisher of the journal. 0 International Journal of Business and Management (ISSN 1833-3850), Vol. 4(3), pp. 43-51, 2009 Relationship between Interest Rate and Stock Price: Empirical Evidence from Developed and Developing Countries Abstract Stock exchange and interest rate are two crucial factors of economic growth of a country. The impacts of interest rate on stock exchange provide important implications for monitory policy, risk management practices, financial securities valuation and government policy towards financial markets. This study seeks evidence supporting the existence of share market efficiency based on the monthly data from January 1988 to March 2003 and also shows empirical relationship between stock index and interest rate for fifteen developed and developing countries- Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Germany, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippine, S.