The FISA Coaching Development Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011-12

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011–2012 Rowing Rowing Australia Office Address: 21 Alexandrina Drive, Yarralumla ACT 2600 Postal Address: PO Box 7147, Yarralumla ACT 2600 Phone: (02) 6214 7526 Rowing Australia Fax: (02) 6281 3910 Website: www.rowingaustralia.com.au Annual Report 2011–2012 Winning PartnershiP The Australian Sports Commission proudly supports Rowing Australia The Australian Sports Commission Rowing Australia is one of many is the Australian Government national sporting organisations agency that develops, supports that has formed a winning and invests in sport at all levels in partnership with the Australian Australia. Rowing Australia has Sports Commission to develop its worked closely with the Australian sport in Australia. Sports Commission to develop rowing from community participation to high-level performance. AUSTRALIAN SPORTS COMMISSION www.ausport.gov.au Rowing Australia Annual Report 2011– 2012 In appreciation Rowing Australia would like to thank the following partners and sponsors for the continued support they provide to rowing: Partners Australian Sports Commission Australian Olympic Committee State Associations and affiliated clubs Australian Institute of Sport National Elite Sports Council comprising State Institutes/Academies of Sport Corporate Sponsors 2XU Singapore Airlines Croker Oars Sykes Racing Corporate Supporters & Suppliers Australian Ambulance Service The JRT Partnership contentgroup Designer Paintworks/The Regatta Shop Giant Bikes ICONPHOTO Media Monitors Stage & Screen Travel Services VJ Ryan -

TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL 2021 World Rowing Cup III Sabaudia, Italy

4-6 JUNE TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL 2021 World Rowing Cup III Sabaudia, Italy WELCOME TO SABAUDIA 2 TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL 2021 World Rowing Cup III Sabaudia, Italy ORGANISING COMMITTEE MAIN PARTNER PROVINCIA CITTÀ DI DI LATINA SABAUDIA WITH THE SUPPORT OF COMANDO ARTIGLIERIA CONTROAEREI Fiamme Gialle 3 TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL 2021 World Rowing Cup III Sabaudia, Italy 5 ORGANISING COMMITTEE 8 WORLD ROWING 10 COVID-19 PLAN - PARTICIPANTS GUIDE 14 GENERAL INFORMATION 20 TRAINING & COMPETITION AT THE COURSE 26 TEAM FACILITIES & SERVICES 32 MEDICAL FACILITIES & SERVICES 40 TRANSPORT & PARKING SERVICES FOR TEAMS 42 ACCOMMODATION 44 FOOD SERVICES 46 ACCREDITATION & INFORMATION CENTRE 48 MEDIA 52 VENUE LAYOUT: BOATHOUSE AREA & FINISH AREA 54 PARKING FOR TEAM VEHICLES & TRAILERS - MAP 56 TRAFFIC RULES: TRAINING & RACING INDEX 4 TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL 2021 World Rowing Cup III Sabaudia, Italy Contact details Comitato Sabaudia MMXX – Sabaudia Rowing Piazza del Comune, 1 04016 Sabaudia (LT) Italy Website: www.sabaudiarowing.com Contact for the OC: Catriona Cameron Email: [email protected] Tel: +39 339 841 0118 ORGANISING COMMITTEE 5 TEAM MANAGERS MANUAL 2021 World Rowing Cup III Sabaudia, Italy Organising Committee Board President Alessio Sartori, City of Sabaudia Vice President Alessio Palombi, Italian NOC Councillor Luigi Matteoli, Province of Latina Councillor Giuseppe Abbagnale, Italian NF Partner Roberto Tavani, Lazio Region Partner Sergio Lamanna, Italian Navy Board Assistant Mauro Bruno Legal Consultant Claudia Di Troia -

Oar Manual(PDF)

TABLE OF CONTENTS OAR ASSEMBLY IMPORTANT INFORMATION 2 & USE MANUAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS 3 ASSEMBLY Checking the Overall Length of your Oars .......................4 Setting Your Adjustable Handles .......................................4 Setting Proper Oar Length ................................................5 Collar – Installing and Positioning .....................................5 Visit concept2.com RIGGING INFORMATION for the latest updates Setting Inboard: and product information. on Sculls .......................................................................6 on Sweeps ...................................................................6 Putting the Oars in the Boat .............................................7 Oarlocks ............................................................................7 C.L.A.M.s ..........................................................................7 General Rigging Concepts ................................................8 Common Ranges for Rigging Settings .............................9 Checking Pitch ..................................................................10 MAINTENANCE General Care .....................................................................11 Sleeve and Collar Care ......................................................11 Handle and Grip Care ........................................................11 Evaluation of Damage .......................................................12 Painting Your Blades .........................................................13 ALSO AVAILABLE FROM -

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2017

Rowing Australia Annual Report 2017 In appreciation Rowing Australia would like to thank the following partners and sponsors for the continued support they provide to rowing: Partners Australian Sports Commission Australian Institute of Sport Australian Olympic Committee Australian Paralympic Committee State Associations and affiliated clubs National Institute Network comprising State Institutes/Academies of Sport World Rowing (FISA) Strategic Event Partners Destination New South Wales Major Sponsors Hancock Prospecting Georgina Hope Foundation Sponsors Aon Risk Solutions 776BC Tempur Croker Oars Sykes Racing Filippi Corporate Supporters & Suppliers Ambulance Services Australia The JRT Partnership Corporate Travel Management VJ Ryan & Co iSENTIA Key Foundations National Bromley Trust Olympic Boat Fleet Trust Bobby Pearce Foundation Photo Acknowledgements Igor Meijjer Narelle Spangher Delly Carr Ron Batt Brett Frawley 2 Rowing Australia Annual Report 2017 Contents Rowing Australia Limited 2017 Office Bearers 4 Company Directors and Chief Executive Officer 6 President’s Report 9 Message from the Australian Sports Commission 11 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 12 Competition Report 17 Development Report 20 High Performance Report 23 Athletes’ Commission Report 28 Commercial and Communications Report 29 The Bobby Pearce Foundation 30 Obituaries 31 Awards 32 Around the States and Territories 35 Australian Capital Territory 35 New South Wales 37 Queensland 38 South Australia 40 Tasmania 42 Victoria 43 Western Australia 44 Australian Senior -

Ranking 2019 Po Zaliczeniu 182 Dyscyplin

RANKING 2019 PO ZALICZENIU 182 DYSCYPLIN OCENA PKT. ZŁ. SR. BR. SPORTS BEST 1. Rosja 384.5 2370 350 317 336 111 33 2. USA 372.5 2094 327 252 282 107 22 3. Niemcy 284.5 1573 227 208 251 105 17 4. Francja 274.5 1486 216 192 238 99 15 5. Włochy 228.0 1204 158 189 194 96 10 6. Wielka Brytania / Anglia 185.5 915 117 130 187 81 5 7. Chiny 177.5 1109 184 122 129 60 6 8. Japonia 168.5 918 135 135 108 69 8 9. Polska 150.5 800 103 126 136 76 6 10. Hiszpania 146.5 663 84 109 109 75 6 11. Australia 144.5 719 108 98 91 63 3 12. Holandia 138.5 664 100 84 96 57 4 13. Czechy 129.5 727 101 114 95 64 3 14. Szwecja 123.5 576 79 87 86 73 3 15. Ukraina 108.0 577 78 82 101 52 1 16. Kanada 108.0 462 57 68 98 67 2 17. Norwegia 98.5 556 88 66 72 42 5 18. Szwajcaria 98.0 481 66 64 89 59 3 19. Brazylia 95.5 413 56 63 64 56 3 20. Węgry 89.0 440 70 54 52 50 3 21. Korea Płd. 80.0 411 61 53 61 38 3 22. Austria 78.5 393 47 61 83 52 2 23. Finlandia 61.0 247 30 41 51 53 3 24. Nowa Zelandia 60.0 261 39 35 35 34 3 25. Słowenia 54.0 278 43 38 30 29 1 26. -

Rowing at Canford

1ST VIII - HENLEY ROYAL REGATTA ROWING AT CANFORD Canford School, Wimborne, Dorset BH21 3AD www.canford.com [email protected] From Ian Dryden - Head Coach Facilities and Coaching Rowing is not just FACILITIES a sport, it becomes a way of life. I • Full range of boats for all levels have been part of • 17 Indoor rowing machines this life for over • Fully equipped strength and conditioning 40 years and my gym including cross training facilities and aim as Canford’s spinning bikes Head Coach is to • 25m indoor swimming pool foster that same excitement and passion for rowing that I experienced during my own schooldays. COACHING PROVISION Rowing requires commitment, dedication and Ian Dryden: Head Coach organisation. It is not an easy sport to master, Junior World Championships 2009 and 2011; and the early starts and cold winter days are Coupe de la Jeunesse 2005, 2008 and 2012; a test of one’s mettle but for the determined, Mercantile Rowing Club and Victoria Institute the personal rewards can be great. While of Sport, Melbourne, Australia 2001-2003; it is satisfying for all the hard work to result in achievement at competition level, the real Assistant Coach, Cambridge University, 1994- rewards from rowing comes from being part 2001; GB Senior/U23 Coach 1994/1998. of the Club, part of a team and working with that team to develop your skill to the very Emily Doherty best of your ability. BSc Sport and Exercise Science (Cardiff Met.), Rowers often excel in other areas of school MSc Youth Sports Coaching (South Wales). life. -

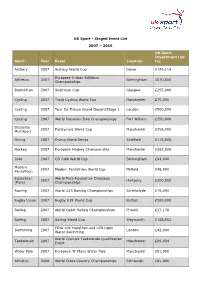

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

2017 World Rowing Event Juries (As at 01.01.2017)

2017 World Rowing Event Juries (as at 01.01.2017) World Rowing Cup 1 – Belgrade, Serbia Jury President LUZAIC Dane SRB 1594 FISA/OC Jury Members MELBOURNE Gregory AUS 1490 FISA STEININGER Birgit AUT 1430 OC MADINA Stefka BUL 1426 OC WITT Thomas GER 1724 FISA KARMAKAR Rupam IND 1538 FISA BORGIOLI Luca ITA 1735 OC STERN Ivo MEX 1341 FISA HINGSTMAN - DOOREN Hubertine NED 0985 FISA WIDUN Anna POL 1619 OC GLIDDON Brendan RSA 1715 FISA FAJFAR Peter SLO 1385 OC DABIC Nikola SRB 1593 OC DZINCIC Igor SRB 1449 OC MILACIC Marko SRB 1450 OC PUSONJIC Dragana SRB 1429 OC SPOOR Humphrey SUI 1603 FISA MAO Ying-Hai TPE 1578 FISA MONES CAMARA Alfredo Martin URU 1757 FISA Spares O'CALLAGHAN Lisa IRL 1719 ES1 BOREL Régis FRA 1565 ES2 OUNIS Houcine TUN 1748 NES1 NGUYEN Hai Duong VIE 1457 NES2 1 World Rowing Cup 2 – Poznan, Poland Jury President WOLNY - MARSZALEK Marta POL 1132 FISA/OC Jury Members DOBLER Angela ARG 1652 FISA VAN BELLE Peter BEL 1244 OC WOOD Debbie CAN 1610 FISA XIE Degang CHN 1123 FISA KYLLESBECH Keld DEN 1259 FISA FORSHAW Eleanor FRA 1672 FISA DENNIS Richard GBR 1529 FISA PANKATZ Daniel GER 1750 OC MESZAROS Judit HUN 1751 OC HWANG Young Sang KOR 1634 FISA WALKER Simon NZL 1554 FISA KARCZEWSKI Maciej POL 1544 OC KNIGAWKA Przemyslaw POL 1470 OC KOBA Andrzej POL 1130 OC KRUPINSKI Adam POL 1645 OC PAWLAK-KUBASEK Malgorzata POL 1618 OC DODDS Bronwyn RSA 1714 FISA LUZAIC Dane SRB 1594 OC Spares BJÖRNSKIÖLD Per SWE 1650 ES1 GATTONI Danilo ITA 1485 ES2 TUN Bo Bo MYA 1705 NES1 GALLAGHER Erin USA 1686 NES2 2 World Rowing Cup 3 – Lucerne, Switzerland -

![1-104 Scope and Exceptions (*) [Meisner, H] Howard Withdrew This Version of the Proposed Rule Change in Favor of the Modified Version Below](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6671/1-104-scope-and-exceptions-meisner-h-howard-withdrew-this-version-of-the-proposed-rule-change-in-favor-of-the-modified-version-below-926671.webp)

1-104 Scope and Exceptions (*) [Meisner, H] Howard Withdrew This Version of the Proposed Rule Change in Favor of the Modified Version Below

Referee Committee Minutes of Meeting November 7, 2017 Telephone Conference Attendance Referee Committee: Andrew Blackwood – Chair Ruth Macnamara – Vice Chair, Secretary Bob Appleyard – Referee College John Musial – Regional Coordinator Representative to Committee Jean Reilly – FISA Terese Friel-Portell – Safety/Referee Utilization Regional Coordinators: Dee McComb, NW Howard Meisner, NE Mike Rosenbaum, SW USRowing Staff: John Wik – Director of Referee Programs Absent: Gevvie Stone – Athlete Representative (work commitment - emailed votes) Rachel Le Mieux – Trials Coordinator (work travel – Ruth had her proxy) Marcus McElhenney – Athlete Representative Derek Blazo, MW Jorge Salas, SE Andy called the meeting to order at 8:34PM EDT. Ruth Macnamara conducted the proposed Rule Change portion of the meeting. The Committee voted on the remaining Rule Changes individually as follows: 1-104 Scope and Exceptions (*) [Meisner, H] Howard withdrew this version of the proposed Rule change in favor of the modified version below. Current Rule: 1-104 Scope and Exceptions (*) (a) These rules shall apply to all rowing Races and Regattas that take place in the United States and that are registered by USRowing. These rules shall not apply to any Races or Regattas that are within the exclusive jurisdiction and control of FISA. 1 (b) Any exceptions or amendments to these rules must be described in detail to USRowing at the time of registration, publicized in writing and distributed to every competing Team. USRowing may take the extent and nature of variation into account in determining whether to register a Regatta. (c) Subsection (b) above notwithstanding, there shall be no exceptions or amendments to any provision designated as absolutely binding. -

Rowing Club Study Guide 2016

ROWING CLUB STUDY GUIDE 2016 This study guide is a reference of topics related to rowing club and was created in collaboration with Irene Lysenko, Head of Training at Great Salt Lake Rowing and Utah State Parks and Recreation ROWING CLUB STUDY GUIDE Before the Row 1. Each club should have a safety committee that will develop and annually review all the safety rules, protocols and procedures. 2. All rowers must be able to pass a swim test, preferably including putting on a life jacket while in the water. Wearable/Safety Requirements 1. When carrying passengers for hire, or leading (coaching) other boats, the Captain/Guide/Coach is responsible for the passengers on their vessel or in guided rowing shells to be in compliance with all PFD requirements. Each vessel may have, for each person on board or in guided boats, one PFD, which is approved for the type of use by the commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard. All personal Flotation Devices (PFDs) must be used according to the conditions or restrictions listed on the U.S. Coast Guard Approval Label. Each Personal Flotation Device (PFD) shall be: . In serviceable condition; . Legally marked with the U.S. Coast Guard approval number; and . Of an appropriate size for the person for whom it is intended. 2. Know that your shell has been designed for flotation. Your boat is not a Personal Flotation Device (PFD); it is an emergency flotation device and your oars are neither a personal or emergency flotation device. All unaccompanied boats must carry appropriate Coast Guard approved PFDs. -

UK Sport - Staged Event List

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

Ranking 2018 Po Zaliczeniu 120 Dyscyplin

RANKING 2018 PO ZALICZENIU 120 DYSCYPLIN OCENA PKT. ZŁ. SR. BR. SPORTS BEST 1. Rosja 238.5 1408 219 172 187 72 16 2. USA 221.5 1140 163 167 154 70 18 3. Niemcy 185.0 943 140 121 140 67 7 4. Francja 144.0 736 101 107 118 66 4 5. Włochy 141.0 701 98 96 115 63 8 6. Polska 113.5 583 76 91 97 50 8 7. Chiny 108.0 693 111 91 67 35 6 8. Czechy 98.5 570 88 76 66 43 7 9. Kanada 92.5 442 61 60 78 45 5 10. Wielka Brytania / Anglia 88.5 412 51 61 86 49 1 11. Japonia 87.5 426 59 68 54 38 3 12. Szwecja 84.5 367 53 53 49 39 3 13. Ukraina 84.0 455 61 65 81 43 1 14. Australia 73.5 351 50 52 47 42 3 15. Norwegia 72.5 451 66 63 60 31 2 16. Korea Płd. 68.0 390 55 59 52 24 3 17. Holandia 68.0 374 50 57 60 28 3 18. Austria 64.5 318 51 34 46 38 4 19. Szwajcaria 61.0 288 41 40 44 33 1 20. Hiszpania 57.5 238 31 34 46 43 1 21. Węgry 53.0 244 35 37 30 27 3 22. Nowa Zelandia 42.5 207 27 35 29 25 2 23. Brazylia 42.0 174 27 20 26 25 4 24. Finlandia 42.0 172 23 23 34 33 1 25. Białoruś 36.0 187 24 31 29 22 26.