Early Cape Farmsteads World Heritage Site Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heritage Western Cape Notification of Intent to Develop

Draft 2: 11/2005 Heritage Western Cape Notification of Intent to Develop Section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act (Act No. 25, 1999) Section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act requires that any person who intends to undertake certain categories of development in the Western Cape (see Part 1) must notify Heritage Western Cape at the very earliest stage of initiating such a development and must furnish details of the location, nature and extent of the proposed development. This form is designed to assist the developer to provide the necessary information to enable Heritage Western Cape to decide whether a Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) will be required, and to establish the appropriate scope of and range of skills required for the HIA. Note: This form must be completed when the proposed development does not fulfil the criteria for Environmental Impact Assessment as set out in the EIA regulations. Its completion is recommended as part of the EIA process to assist in establishing the requirements of Heritage Western Cape with respect to the heritage component of the EIA. 1. It is recommended that the form be completed by a professional familiar with heritage conservation issues. 2. The completion of Section 7 by heritage specialists is not mandatory, but is recommended in order to expedite decision-making at notification stage. If Section 7 is completed: • Section 7.1 must be completed by a professional heritage practitioner with skills and experience appropriate to the nature of the property and the development proposals. • Section 7.2 must be completed by a professional archaeologist or palaeontologist. -

Transforming the Iziko Bo-Kaap Museum Helene Vollgraaff 1

Transforming the Iziko Bo-Kaap Museum Helene Vollgraaff 1 Introduction The Bo-Kaap Museum, managed by Iziko Museums of Cape Town 2, was established in 1978 as a house museum showing the lifestyle of a typical “Cape Malay” family of the 19 th century. The well-known University of Cape Town Orientalist, Dr. I.D. du Plessis, was the driving force behind the establishment of the museum. From the start, the Bo-Kaap Museum was heavily criticized for its Orientalist approach. In true I.D. du Plessis style, Cape Muslims were depicted as a separate cultural group with an exotic and charming lifestyle that seperated them from the rest of local society. The exhibitions and programmes of the museum tended to focus on Islam as an all-consuming identity and emphasized customs that distinguished Cape Muslims from other religious and cultural groups in Cape Town. The result was a skewed representation that did not do justice to the diversity within the Cape Muslim community and was silent about aspects of integration between the Muslim and broader Cape Town communities. 3 In 2003, Iziko Museums launched a project to redevelop the Bo-Kaap Museum as a social history museum with Islam at the Cape and the history of the Bo-Kaap as its main themes. This approach allowed the museum to challenge its own Orientalist roots and to introduce exhibitions dealing with contemporary issues. As an interim measure, Iziko developed a series of small temporary exhibitions and public programmes that together signaled Iziko Museum’s intent to change the content and style of the museum. -

An Exhibition of South African Ceramics at Iziko Museums Article by Esther Esymol

Reflections on Fired – An Exhibition of South African Ceramics at Iziko Museums Article by Esther Esymol Abstract An exhibition dedicated to the history and development of South African ceramics, Fired, was on show at the Castle of Good Hope in Cape Town, South Africa, from 25th February 2012 until its temporary closure on 28th January 2015. Fired is due to reopen early 2016. The exhibition was created from the rich array of ceramics held in the permanent collections of Iziko Museums of South Africa. Iziko was formed in 1998 when various Cape Town based museums, having formerly functioned separately, were amalgamated into one organizational structure. Fired was created to celebrate the artistry of South African ceramists, showcasing works in clay created for domestic, ceremonial or decorative purposes, dating from the archaeological past to the present. This article reflects on the curatorial and design approaches to Fired, and the various themes which informed the exhibition. Reference is also made to the formation of the Iziko ceramics collections, and the ways in which Fired as an exhibition departed from ceramics displays previously presented in the museums that made up the Iziko group. Key words ceramics, studio pottery, production pottery, Community Economic Development (CED) potteries, museums Introduction Fired – an Exhibition of South African Ceramics celebrated South Africa’s rich and diverse legacy of ceramic making. The exhibition showcased a selection of about two hundred ceramic works, including some of the earliest indigenous pottery made in South Africa, going back some two thousand years, through to work produced by contemporary South African ceramists. The works were drawn mainly from the Social History Collections department of Iziko Museums of South Africa.1 Design and curatorial approaches Fired was exhibited within an evocative space in the Castle, with arched ceilings and columns and presented in two large elongated chambers (Fig.1). -

Drakenstein Heritage Survey Reports

DRAKENSTEIN HERITAGE SURVEY VOLUME 1: HERITAGE SURVEY REPORT October 2012 Prepared by the Drakenstein Landscape Group for the Drakenstein Municipality P O BOX 281 MUIZENBERG 7950 Sarah Winter Tel: (021) 788-9313 Fax:(021) 788-2871 Cell: 082 4210 510 E-mail: [email protected] Sarah Winter BA MCRP (UCT) Nicolas Baumann BA MCRP (UCT) MSc (OxBr) D.Phil(York) TRP(SA) MSAPI, MRTPI Graham Jacobs BArch (UCT) MA Conservation Studies (York) Pr Arch MI Arch CIA Melanie Attwell BA (Hons) Hed (UCT) Dip. Arch. Conservation (ICCROM) Acknowledgements The Drakenstein Heritage Survey has been undertaken with the invaluable input and guidance from the following municipal officials: Chantelle de Kock, Snr Heritage Officer Janine Penfold, GIS officer David Delaney, HOD Planning Services Anthea Shortles, Manager: Spatial Planning Henk Strydom, Manager: Land Use The input and comment of the following local heritage organizations is also kindly acknowledged. Drakenstein Heritage Foundation Paarl 300 Foundation LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS The following abbreviations have been used: General abbreviations HOZ: Heritage Overlay Zone HWC: Heritage Western Cape LUPO: Land Use Planning Ordinance NHRA: The National Heritage Resources act (Act 25 of 1999) PHA: Provincial Heritage Authority PHS: Provincial Heritage Site SAHRA: The South African Heritage Resources Agency List of abbreviations used in the database Significance H: Historical Significance Ar: Architectural Significance A: Aesthetic Significance Cx: Contextual Significance S: Social Significance Sc: Scientific Significance Sp: Spiritual Significance L: Linguistic Significance Lm: Landmark Significance T: Technological Significance Descriptions/Comment ci: Cast Iron conc.: concrete cor iron: Corrugated iron d/s: double sliding (normally for sash windows) fb: facebrick med: medium m: metal pl: plastered pc: pre-cast (normally concrete) s/s: single storey Th: thatch St: stone Dating 18C: Eighteenth Century 19C: Nineteenth Century 20C: Twentieth Century E: Early e.g. -

A Risk Based Approach to Heritage Management in South Africa

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-2/W15, 2019 27th CIPA International Symposium “Documenting the past for a better future”, 1–5 September 2019, Ávila, Spain A RISK BASED APPROACH TO HERITAGE MANAGEMENT IN SOUTH AFRICA. C.Jackson a , L.Mofutsanyanaa,, N.Mlungwana a aSouth African Heritage Resources Agency, 111 Harrington Street Cape Town 8000, South Africa - [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Commission II, WG II/8 KEY WORDS: Digital Inventories, Heritage Management, South Africa, SAHRIS, Risk Analysis ABSTRACT: The management of heritage resources within the South African context is governed by the National Heritage Resources Act, act 25 of 1999 (NHRA). This legislation calls for an integrated system of heritage management that allows for the good governance of heritage across the three tiers of government. The South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), as the national body responsible for heritage management, is mandated to compile and maintain an inventory of the national estate. The South African Heritage Resources Information System (SAHRIS) was designed to facilitate this mandate as well as provide a management platform through which the three-tiers of governance can be integrated. This vision of integrated management is however predicated on the implementation of the three-tier system of heritage management, a system which to date has not been fully implemented, with financial and human resource constraints being present at all levels. In the absence of the full implementation of this system and the limited resources available to heritage authorities, we argue that a risk based approach to heritage management will allow under resourced heritage authorities in South Africa to prioritise management actions and ensure mitigations are in place for at risk heritage resources. -

Annexure D Annexure D

ANNEXURE D ANNEXURE D ARCHAEOLOGIGAL CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT Guidelines for Property Owners and Managers Groot Constantia and Vergelegen Estates Revised May 2018 SAFEGUARDING ARCHAEOLOGY Archaeology is the study of human cultures by analysing the material remains (sites and artefacts) that people left behind, from the distant to recent past. Archaeological sites are non-renewable, very susceptible to disturbance and are finite in number. They are protected by law. Archaeological remains can be exposed during activities such as digging holes and trenching, or clearing ground, or when doing building maintenance and construction – or merely by chance discovery. Unlike the natural environment, a deposit that has been bulldozed away by mistake cannot be restored. The purpose of this document is to promote preservation of archaeological information while minimising disruption to projects or routine activities. It provides procedures to follow in the case of planned interventions and developments, or in the case of a chance archaeological find, to ensure that artefacts and sites are documented and protected. Archaeological sites are protected by the National Heritage Resources Act (Act 25 of 1999) (NHRA). According to the NHRA, all material remains resulting from human activity that have been abandoned for more than 100 years ago are the property of the State and may not be removed from their place of origin without a permit from the provincial heritage resources authority (Heritage Western Cape (HWC)) or from the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA). See HWC Regulations. In addition, the National Environmental Management Act (Act 107 of 1998) makes provision for assessment of impacts that activities such as large developments will have on archaeological heritage. -

Activities List City Specialists Contents

ACTIVITIES LIST CITY SPECIALISTS CONTENTS Taj Cape Town offers our professional City Specialist Guides and Concierge CHAPTER 1: DISCOVERING CAPE TOWN team to introduce to you a selection of some of the highlights and little known gems of our beautiful Mother City. CHAPTER 2: LIVING THE HISTORY OF CAPE TOWN All destinations are a few minutes walk or a short taxi ride from Taj Cape Town. CHAPTER 3: SEEKING ADRENALIN IN CAPE TOWN We have chosen places and experiences which we believe are truly representative of the richness, diversity, quality and texture of our famous city. CHAPTER 4: SHOPPING FOOTSTEPS TO FREEDOM CITY WALKING TOUR CHAPTER 5: LAND ACTIVITIES Taj Cape Town is host to ‘Footsteps to Freedom’, a guided walking tour around key heritage sites in Cape Town’s historic city centre, as part of the hotel’s CHAPTER 6: SEA ACTIVITIES unique service offerings. CHAPTER 7: KIDDIES ACTIVITIES MANDELA IN CAPE TOWN: FROM PRISONER TO PRESIDENT Gain insight into the history of Mandela’s personal journey as you follow in his footsteps through Cape Town, and experience first-hand the landmarks and legacy of South Africa’s most treasured icon. Duration: 2½ Hours Price: R220 per person Footsteps to Freedom: 10h30; Tuesday - Saturday Mandela; From Prisoner to President: 10h30; Wednesday & Saturday Professional tour guides will meet you in the Lobby of the hotel at 10h20. For more information and bookings, contact: [email protected] or visit our City Specialist Guides in the Hotel Lobby, Tuesday to Saturday from 08h30 – 10h30. All prices are subject to change without prior notice. -

The Ecology of Large Herbivores Native to the Coastal Lowlands of the Fynbos Biome in the Western Cape, South Africa

The ecology of large herbivores native to the coastal lowlands of the Fynbos Biome in the Western Cape, South Africa by Frans Gustav Theodor Radloff Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Science (Botany) at Stellenbosh University Promoter: Prof. L. Mucina Co-Promoter: Prof. W. J. Bond December 2008 DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 24 November 2008 Copyright © 2008 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii ABSTRACT The south-western Cape is a unique region of southern Africa with regards to generally low soil nutrient status, winter rainfall and unusually species-rich temperate vegetation. This region supported a diverse large herbivore (> 20 kg) assemblage at the time of permanent European settlement (1652). The lowlands to the west and east of the Kogelberg supported populations of African elephant, black rhino, hippopotamus, eland, Cape mountain and plain zebra, ostrich, red hartebeest, and grey rhebuck. The eastern lowlands also supported three additional ruminant grazer species - the African buffalo, bontebok, and blue antelope. The fate of these herbivores changed rapidly after European settlement. Today the few remaining species are restricted to a few reserves scattered across the lowlands. This is, however, changing with a rapid growth in the wildlife industry that is accompanied by the reintroduction of wild animals into endangered and fragmented lowland areas. -

THE SUPREME COURT of APPEAL of SOUTH AFRICA JUDGMENT Reportable Case No: 974/2015 in the Matter Between: PETER GEES APPELLA

THE SUPREME COURT OF APPEAL OF SOUTH AFRICA JUDGMENT Reportable Case No: 974/2015 In the matter between: PETER GEES APPELLANT and THE PROVINCIAL MINISTER OF CULTURAL AFFAIRS AND SPORT, WESTERN CAPE FIRST RESPONDENT THE CHAIRPERSON, INDEPENDENT APPEAL TRIBUNAL SECOND RESPONDENT HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE THIRD RESPONDENT THE CITY OF CAPE TOWN FOURTH RESPONDENT CITY BOWL RATEPAYERS’ AND RESIDENTS’ ASSOCIATION FIFTH RESPONDENT Neutral citation: Gees v The Provincial Minister of Cultural Affairs and Sport (974/2015) [2015] ZASCA 136 (29 September 2016) Coram: Maya DP, Bosielo and Seriti JJA and Fourie and Dlodlo AJJA Heard: 15 September 2016 Delivered: 29 September 2016 Summary: Provincial heritage resources authority granting a permit in terms of s 34 of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 for the demolition of a structure older than 60 years situated on a property with no formal heritage status: in so doing conditions were imposed controlling future development on the property: held that such conditions were lawfully imposed. 2 _______________________________________________________________ ORDER ________________________________________________________________ On appeal from: Western Cape Division of the High Court, Cape Town (Weinkove AJ sitting as court of first instance): The appeal is dismissed with costs, including the costs of two counsel. ________________________________________________________________ JUDGMENT ________________________________________________________________ Fourie AJA (Maya DP, Bosielo and Seriti JJA and Dlodlo AJA concurring) [1] The issue in this appeal is whether the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (the Act) authorises a provincial heritage resources authority, when granting a permit for the demolition of an entire structure which is older than 60 years, situated on a property with no formal heritage status, may lawfully impose conditions controlling future development on the property. -

Botanical Assessment-N2 Arrestor Bed Sir Lowrys Pass Rev

Botanical Assessment for the proposed Arrestor Bed on the N2 National Highway at Sir Lowry’s Pass, City of Cape Town, Western Cape Province Report by Dr David J. McDonald Bergwind Botanical Surveys & Tours CC. 14A Thomson Road, Claremont, 7708 Tel: 021-671-4056 Fax: 086-517-3806 Report prepared for Aurecon South Africa (Pty) Ltd August 2015 Botanical Assessment: Arrestor Bed, N2 Highway, Sir Lowry’s Pass EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The botanical assessment reported here was commissioned to support the environmental authorization process required for the proposed construction of an arrestor bed on the south side of the N2 National Highway at the base of Sir Lowry’s Pass, near Somerset West, Western Cape Province. Only one alternative layout was investigated and assessed. The study area is found in the transition zone or ecotone between Boland Granite Fynbos and Cape Winelands Shale Fynbos. Both are regarded as Vulnerable on a national conservation scale. The arrestor bed site would cover less than 0.5 ha and most of the vegetation found is natural. There are small clusters of woody invasive aliens as well as invasive grasses, notably Kikuyu grass. These plant species should be controlled prior to commencement of construction. Although there would be complete loss of natural fynbos vegetation on the site the impact assessment indicates that since the area is small and linear the overall direct impact of the arrestor bed in the construction and operational phases would be Minor negative . On-site mitigation to accommodate the loss of the fynbos vegetation would not be possible but other mitigation measures to avoid disturbance impacts beyond the footprint should be implemented. -

Places to Enjoy, Please Visit Capetownccid.Org Play Be Entertained 24/7

capeBEST OF town 2018 e copy re r f You 300pla ces to enjoy n i o u r Cen tral City visit shop eat play stay Must-see museums, From luxury All the best Plan your Hotels, galleries, cultural boutiques & restaurants & social calendar guesthouses and attractions & speciality shops to night time the quick & backpackers to suit historic spaces trndy flaarts dining spots easy way every traveller + Over 900 more places on our website. Visit capetownccid.org @CapeTownCCID CapeTownCCID 05 VISIT Galleries, museums, city sights and public spaces 17 SHOP Fashion, gifts, décor and books FROM THE 29 EAT Cafés, bakeries, EDITOR restaurants and markets Through this guide, brought to you by the Cape Town Central 45 PLAY Theatres, pubs City Improvement District and clubs (CCID), South Africa’s Mother City continues to welcome 53 STAY enthusiastic visitors in ever- Hotels and backpackers growing numbers – up to some 1,2-million in 2017. The 67 ESSENTIALS inner Central City of Cape Useful info Town is an especially vibrant and resources draw card, presenting a BEST OF cape town 2018 copy ICONS TO NOTE ee dizzying range of options for fr r You shopping, gallery-hopping 300place WALLET- A SPECIAL s to en joy in o u r Ce FRIENDLY TREAT OCCASION ntral and stopping for the night! City visit shop eat play stay Must-see museums, From luxury All the best Plan your Hotels, galleries, cultural boutiques & restaurants & social calendar guesthouses and attractions & speciality shops to night time the quick & backpackers to suit WHEELCHAIR- CHILD- CLOSEST PARKING historic spaces trndy fl aarts dining spots easy way every traveller Its entertainment offerings + P Over more places on our website visit capetownccid.org FRIENDLY 900 FRIENDLY (SEE PAGE 70) @CapeTownCCID CapeTownCCID – from cabaret and classical concerts to theatres, clubs To obtain a copy of this magazine, contact Aziza Patandin and pubs – are the rival of any at the CCID on 021 286 0830 or [email protected] international CBD. -

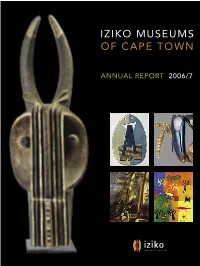

AR 2006 2007.Pdf

��������������� ������������ ��������������������� ����� ����� �������������������� �������������������� ���������������������� Iziko Museums of Cape Town ANNUAL REPORT for the period 1 April 2006 to 31 March 2007 Published by Iziko Museums of Cape Town 2007 ISBN 978-1-919944-33-3 The report is also available on the Iziko Museums of Cape Town website at http://www.iziko.org.za/iziko/annreps.html ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The managers and staff of all the departments of Iziko are thanked for their contributions. Editor: Nazeem Lowe Design & Layout: Welma Odendaal Printed by Creda Communications COVER PHOTOGRAPHS FRONT A. Unknown artist, Liberia. Mask, Dan Ngere, wood. Sasol Art Museum. ‘Picasso and Africa’ exhibition. B. Pablo Picasso. Composition 22 April 1920. Gouache and Indian ink. Musée Picasso, Paris. Photo RMN. © Succession Picasso 2006 – DALRO. ‘Picasso and B C Africa’ exhibition. A C. Head detail of female wasp, Crossogaster inusitata. Natural History D E Collections Department, Entomology collections. D. John Thomas Baines, 1859. Baines returning to Cape Town on the gunboat Lynx in December 1859. Iziko William Fehr Collection. E. Flai Shipipa, (n.d.) 1995. Two houses and three buck. Oil on canvas. ‘Memory and Magic’ exhibition. BACK F G F. ‘Separate is not Equal’ exhibition, Iziko Slave Lodge. G. Visitors queuing at the Iziko SA National Gallery, ‘Picasso and Africa’ exhibition. H I H. Drumming workshop, education programme, Iziko Slave Lodge. I. Taxidermist George Esau, showing learners a mounted penguin skeleton, education outreach programme. J J. Jobaria skeleton, nearing completion. For the ‘African Dinosaurs’ exhibition, Iziko SA Museum. CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMATION 4 1.1. Submission of the annual report to the executive authority 4 1.2.