EITI International Secretariat Validation of Nigeria Report On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Report Fifth Council Meeting and Fourth Conference of ASSECAA Held in Rabat Morocco Day One 12Th November 2009

ASSOCIATION OF SENATES, SHOORA AND رابطة مجالس الشيوخ والشورى والمجالس EQUIVALENT COUNCILS المماثلة في أفريقيا والعالم العـربـي IN AFRICA AND THE ARAB WORLD ASSOCIATION DES SENATS, SHOORA ET CONSEILS EQUIVALENTS D’AFRIQUE ET DU MONDE ARABE Interim Report Fifth Council Meeting and Fourth Conference of ASSECAA Held in Rabat Morocco Day One 12th November 2009. COUNCIL MEETING The Outgoing Chairman of the Association, H.E Ali Yahiya Abdallah in the chair 1.0 Preamble 1.1 Under the supreme auspices of His Majesty, Mohammed VI, King of the Kingdom of Morocco and at the kind invitation of H.E Dr. Mohammed Al- Cheikh Baidallah, Speaker of the House of Counselors of Morocco, the fourth conference and the fifth Council meeting of the Association of Senates, Shoora and Equivalent Councils in Africa and the Arab world (ASSECAA) were held in Rabat, Morocco, from 12-13 November 2009. 1.2 The meetings were held in joyous atmosphere of optimism, constructive understanding and common keenness on enhancing cooperation and buttressing common interests of Africa and Arab world. ASSOCIATION OF SENATES, SHOORA AND رابطة مجالس الشيوخ والشورى والمجالس EQUIVALENT COUNCILS المماثلة في أفريقيا والعالم العـربـي IN AFRICA AND THE ARAB WORLD ASSOCIATION DES SENATS, SHOORA ET CONSEILS EQUIVALENTS D’AFRIQUE ET DU MONDE ARABE 1.3 The meetings were characterized by fervent enthusiasm and determination on the part of member countries, to attain the objectives for which the Association was established. 1.4 Foremost among such objectives is the consolidation of economic cooperation, bicameralism, development of common action at the political, socio-economic and cultural levels and coordination among the countries of the two regions with the aim of surmounting all obstacles to stability and development, eliminating all causes of tension and conflicts and harnessing the abundant potentials, available in the region, for the betterment of its nations. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA VOTES and PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 9Th June, 2015

8TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION No.1 1 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS Tuesday, 9th June, 2015 1. The Senate met at 10: 00 a.m. pursuant to the proclamation by the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Muhammadu Bubari. //·····\;·n~l'. 1r) I" .,"-~~:~;;u~~;~)'::.Y1 PRESIDENT, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA Your Excellency, PROCLAMATION FOR THE HOLDING OF THE FIRST SESSION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY WHEREASit is provided in Section 64(3) of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 (As Amended) that the person Elected as President shall have power to issue a proclamation for the holding of the First Session of the National Assembly immediately after his being sworn-in. NOW,mEREFORE,I Muhammadu Buhari, President, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, in exercise of thepowers bestowed upon me by Section (64) aforesaid, and of all other powers enabling me in that behalf hereby proclaim that the First Session of the eight (8h) National Assembly shall hold at 10.00 a.m. on Tuesday, 9th June, 2015 in the National Assembly, Abuja. Given under my hand and the Public Seal of the Federal Republic of Nigeria at Abuja, this P Day of June, 2015. Yours Sincerely, (Signed) Muhammadu Buhari President, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces Federal Republic of Nigeria 2. At 10.04 a.m. the Clerk to the National Assembly called the Senate to order and informed Senators-Elect that writs had been received in respect of the elections held on 28th March, 2015 in accordance with the Constitution. -

Nnamdi Kanu Leader of the Indigenous People Of

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 05/15/2020 6:30:11 PM April 29, 2020 Hon. David Perdue United States Member of Congress 455 Russell Senate Office Building Washington, DC 20510 Dear Senator Perdue, As concerned citizens, constituents, and members of the Nigerian diaspora in the United States, we write to call your attention to the volatile and violent situation in Nigeria in which minority groups and those with dissenting views, including the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), are being victimized and persecuted with impunity while the Buhari government stands silently by - and in some instances participates. Without urgent attention and the assistance of the international community, conditions will continue to deteriorate, compromising U.S. interests in the region and repeating the atrocities and bloodshed the world has witnessed far too often in this part of the globe. Over the past five years, there has been a sharp increase in criminality and spreading insecurity; widespread failure by the federal authorities to investigate and hold perpetrators accountable, even for mass killings; and a generalized break down of the rule of law. This has been exacerbated by the proliferation of small and military-grade weapons made readily available as a result of regional instability and originating from as far north as the Libyan conflict. Despite this recognized humanitarian crisis, the Nigerian government has increasingly dismissed religious and human rights concerns, and continued to perpetrate violations of its own. There are many documented incidences of violence led by state security actors, but no mechanisms by which to hold the Administration accountable. In its 2018 Nigeria Human Rights Report, the U.S. -

SENATE of the FEDERAL REPUBLIC of NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Thursday, 12Th March, 2020

9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY FIRST SESSION NO. 118 437 SENATE OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA ORDER PAPER Thursday, 12th March, 2020 1. Prayers 2. Approval of the Votes and Proceedings 3. Oaths 4. Announcements (if any) 5. Petitions PRESENTATION OF BILLS 1. Animal Health and Husbandry Technologists Registration Board (Est, etc) Bill, 2020 (HB. 374) - First Reading Sen. Abdullahi, Yahaya Abubakar (Kebbi North-Senate Leader). 2. 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Alteration) Bill, 2020 (SB. 361) - First Reading Sen. Tanimu, Philip Aduda (F.C.T Senate). 3. 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Alteration) Bill, 2020 (SB. 351) - First Reading Sen. Ekwunife, Uche Lilian (Anambra Central). 4. 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (Alteration) Bill, 2020 (SB.398) - First Reading Sen. Dahiru, Aishatu Ahmed (Adamawa Central). 5. Open Defecation (Prohibition) Bill, 2020 (SB. 337)- First Reading Sen. Ordia, Akhimienmona Clifford (Edo Central). ORDERS OF THE DAY CONSIDERATION OF BILLS 1. A Bill for an Act to alter the provisions of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 to provide for the amendment of Sections 65 (2) (a), 131 (d), Section 106 (c) and Section 177 (d) therein, to provide for minimum qualification for election into the National and States Assembly, Office of the President and Governors, and other related matters, 2020 (SB. 75)- Second Reading Sen. Gyang, Istifanus Dung (Plateau North). 2. A BilI for an Act to alter the provisions of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 to specify the period within which the President or Governor of a State presents the Appropriation Bill before the National Assembly of House of Assembly and for other related matters, 2020 (SB. -

COMPARATIVE POLITICS Directorate Of

COMPARATIVE POLITICS MA [Political Science] Second Semester POLS 802C First Semester II (POLS 702C) [ENGLISH EDITION] Directorate of Distance Education TRIPURA UNIVERSITY Reviewer Dr Nivedita Giri Assistant Professor, Jesus & Mary College, University of Delhi Authors: Dr Saidur Rahman (Unit: 1.2) © Dr. Saidur Rahman, 2016 Dr Biswaranjan Mohanty (Units: 2.2, 3.2, 4.2.2, 4.5) © Dr. Biswaranjan Mohanty, 2016 Dr Jyoti Trehan Sharma and Dr Monica M Nandi (Units: 2.6-2.6.1, 4.6) © Dr Jyoti Trehan Sharma and Dr Monica M Nandi, 2016 Vikas Publishing House (Units: 1.0-1.1, 1.3, 1.4-1.12, 2.0-2.1, 2.2.1, 2.3-2.5, 2.6.2-2.12, 3.0-3.1, 3.3-3.10, 4.0-4.2.1, 4.3-4.4, 4.7-4.11) © Reserved, 2016 Books are developed, printed and published on behalf of Directorate of Distance Education, Tripura University by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material, protected by this copyright notice may not be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form of by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the DDE, Tripura University & Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. -

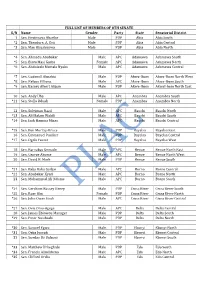

Full List of Members of the 8Th Senate

FULL LIST OF MEMBERS OF 8TH SENATE S/N Name Gender Party State Senatorial District 1 Sen. Enyinnaya Abaribe Male PDP Abia Abia South *2 Sen. Theodore. A. Orji Male PDP Abia Abia Central *3 Sen. Mao Ohuabunwa Male PDP Abia Abia North *4 Sen. Ahmadu Abubakar Male APC Adamawa Adamawa South *5 Sen. Binta Masi Garba Female APC Adamawa Adamawa North *6 Sen. Abdulaziz Murtala Nyako Male APC Adamawa Adamawa Central *7 Sen. Godswill Akpabio Male PDP Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom North West *8 Sen. Nelson Effiong Male APC Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom South *9 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Male PDP Akwa-Ibom AkwaI-bom North East 10 Sen. Andy Uba Male APC Anambra Anambra South *11 Sen. Stella Oduah Female PDP Anambra Anambra North 12 Sen. Suleiman Nazif Male APC Bauchi Bauchi North *13 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Male APC Bauchi Bauchi South *14 Sen. Isah Hamma Misau Male APC Bauchi Bauchi Central *15 Sen. Ben Murray-Bruce Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa East 16 Sen. Emmanuel Paulker Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa Central *17 Sen. Ogola Foster Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa West 18 Sen. Barnabas Gemade Male APC Benue Benue North East 19 Sen. George Akume Male APC Benue Benue North West 20 Sen. David B. Mark Male PDP Benue Benue South *21 Sen. Baba Kaka Garbai Male APC Borno Borno Central *22 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Male APC Borno Borno North 23 Sen. Mohammed Ali Ndume Male APC Borno Borno South *24 Sen. Gershom Bassey Henry Male PDP Cross River Cross River South *25 Sen. Rose Oko Female PDP Cross River Cross River North *26 Sen. -

Nigeria's Struggle with Corruption Hearing

NIGERIA’S STRUGGLE WITH CORRUPTION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MAY 18, 2006 Serial No. 109–172 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/international—relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27–648PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 21 2002 12:05 Jul 17, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\AGI\051806\27648.000 HINTREL1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, HOWARD L. BERMAN, California Vice Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DAN BURTON, Indiana ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American ELTON GALLEGLY, California Samoa ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BRAD SHERMAN, California PETER T. KING, New York ROBERT WEXLER, Florida STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts RON PAUL, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York DARRELL ISSA, California BARBARA LEE, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon MARK GREEN, Wisconsin SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada JERRY WELLER, Illinois GRACE F. -

Petro-Violence and the Geography of Conflict in Nigeria's

Spaces of Insurgency: Petro-Violence and the Geography of Conflict in Nigeria’s Niger Delta By Elias Edise Courson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair Professor Ugo G. Nwokeji Professor Jake G. Kosek Spring 2016 Spaces of Insurgency: Petro-Violence and the Geography of Conflict in Nigeria’s Niger Delta © 2016 Elias Edise Courson Abstract Spaces of Insurgency: Petro-Violence and the Geography of Conflict in Nigeria’s Niger Delta by Elias Edise Courson Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael J. Watts, Chair This work challenges the widely held controversial “greed and grievance” (resource curse) narrative by drawing critical insights about conflicts in the Niger Delta. The Niger Delta region of Nigeria has attracted substantial scholarly attention in view of the paradox of poverty and violence amidst abundant natural resources. This discourse suggests that persistent resource- induced conflicts in the region derive from either greed or grievance. Instead, the present work draws inspiration from the political geography of the Niger Delta, and puts the physical area at the center of its analysis. The understanding that the past and present history of a people is etched in their socio-political geography inspires this focus. Whereas existing literatures engages with the Niger Delta as a monolithic domain, my study takes a more nuanced approach, which recognizes a multiplicity of layers mostly defined by socio-geographical peculiarities of different parts of the region and specificity of conflicts its people experience. -

Standing Committees of the 9Th Senate (2019-2023) (Chairmen and Vice Chairmen)

Standing Committees of the 9th Senate (2019-2023) (Chairmen and Vice Chairmen) S/N COMMITTEES CHAIRMAN VICE CHAIRMAN 1. Agriculture and Productivity Sen. Abdullahi Adamu Sen. Bima Mohammed Enagi 2. Air Force Sen Bala Ibn Na’allah Sen. Michael Ama Nnachi 3. Army Sen.Mohammed Ali Ndume Sen. Abba Patrick Moro 4. Anti-Corruption and Sen. Suleiman Kwari Sen. Aliyu Wamakko Financial Crimes 5. Appropriations Sen. Jibrin Barau Sen. Stella Oduah 6. Aviation Sen. Dino Melaye Sen. Bala Ibn Na’allah 7. Banking Insurance and Other Sen. Uba Sani Sen. Uzor Orji Kalu Financial Institutions 8. Capital Market Sen. Ibikunle Amosun Sen. Binos Dauda Yaroe 9. Communications Sen. Oluremi Tinubu Sen. Ibrahim Mohammed Bomai 10. Cooperation and integration Sen. Chimaroke Nnamani Sen. Yusuf Abubukar Yusuf in Africa and NEPAD 11. Culture and Tourism Sen. Rochas Okorocha Sen. Ignatius Datong Longjan 12. Customs, Excise and Tariff Sen. Francis Alimikhena Sen. Francis Fadahunsi 13. Defence Sen. Aliyu Wamakko Sen. Istifanus Dung Gyang 14. Diapsora and NGOs Sen. Surajudeen Ajibola Sen. Ibrahim Yahaya Basiru Oloriegbe 15. Downstream Petroleum Sen. Sabo Mohammed Sen. Philip Aduda Nakudu 16. Drugs and Narcotics Sen. Hezekiah Dimka Sen. Chimaroke Nnamani 17. Ecology and Climate Change Sen. Mohammed Hassan Sen. Olunbunmi Adetunmbi Gusau 18. Education (Basic and Sen. Ibrahim Geidam Sen. Akon Etim Eyakenyi Secondary) 19. Employment, Labour and Sen. Benjamin Uwajumogu Sen. Abdullahi Kabir Productivity Barkiya 20. Environment Sen. Ike Ekweremadu Sen. Hassan Ibrahim Hadeija 21. Establishment and Public Sen. Ibrahim Shekarau Sen. Mpigi Barinada Service 22. Ethics and Privileges Sen. Ayo Patrick Akinyelure Sen. Ahmed Baba Kaita 23. -

Nigeria Energy Sector Transformation, DFID, USAID, and the World Bank

PUBLIC SERVICES INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH UNIT (PSIRU) www.psiru.org 1 Nigeria Energy Sector Transformation, DFID, USAID, and the World Bank Sandra van Niekerk, Yuliya Yurchenko and Jane Lethbridge ‘Nigerians are getting angry. We are asking for a decentralised system of community-controlled solar and wind power. Privatisation doesn’t work on any count’. 1 Ken Henshaw, founding member of Social Action – NGO fighting for energy democracy in Nigeria since 2007 Overview Nigeria has a growing population of more than 179 million and about 8 000 MW of installed electricity capacity but it only generates about 4,000 megawatts. In order to meet the needs of the economy, the government estimates that it needs 40 000 MW by 2020. Demand for electricity far outstrips supply, and many homes and businesses have their own generators, making Nigeria one of the largest markets for individual generators. Temporary diesel-generated capacity provides five times more electricity than the national grid. The country is faced with frequent power outages, and there is a high rate of transmission losses. 2 3 Ken Henshaw, energy democracy activist, claims that ‘in such a huge country with bad infrastructure, it doesn’t make sense to have one central power system’. He argues that the approach of privatisation as a way out of the electricity problems facing the country was imposed on Nigeria by Bretton Woods institutions 4 There is inequality of access so ‘poor Nigerians (67% of the country) cannot get any electricity’. According to Ken Henshaw, there are ‘3 big problems with the new privatized power system. First, the cost of energy has gone up a lot in the 4 years since they agreed the privatization. -

The Institutionalization of Political Power in Africa

THE INSTITUTIONALIZATION OF POLITICAL POWER IN AFRICA Daniel N. Posner and Daniel J. Young Daniel N. Posner is associate professor of political science at the Uni- versity of California–Los Angeles (UCLA) and author of Institutions and Ethnic Politics in Africa (2005). Daniel J. Young is a doctoral candidate in political science at UCLA and is finishing a dissertation on political parties in Africa based on fieldwork in Malawi. On 16 May 2006, after months of intense and divisive national de- bate, the Senate of Nigeria rejected a bill which would have changed that country’s constitution to permit President Olusegun Obasanjo a third term in office. By asserting the supremacy of the constitution (with its two-term limit) over the desires of President Obasanjo’s sup- porters that the popular leader be permitted to run for a third term, the Senate’s vote marked a watershed in Nigeria’s political history. As im- portant as the outcome was the way in which the conflict was resolved— by the votes of duly elected legislators rather than through force or the threat of same. Given that Nigeria’s First and Second Republics (1963– 66 and 1979–83) were overthrown by military coups, the settlement of this political struggle via the Senate chamber rather than the gun barrel represents a major shift in the way that decisions over executive tenure in Nigeria have been made.1 Both the outcome of Obasanjo’s third-term campaign and the pro- cess through which it was reached signal a growing trend in sub-Sa- haran Africa: The formal rules of the game are beginning to matter in ways that they previously have not. -

Sen Senators of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 2011-2015

SEN SENATORS OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA 2011-2015 SEN. ABARIBE ENYINNAYA HARCOURT Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ABIA Party: SEN. NWAOGU NKECHI JUSTINA Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ABIA Party: SEN. CHUKWUMERIJE UCHE Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015); CON View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ABIA Party: SEN. ADUDA PHILIP TANIMU Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ABUJA FCT Party: SEN. JIBRILLA BINDAWA Senator, 7th National Assembly (2001-2015) Alhaji View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ADAMAWA Party: SEN. BARATA AHMED HASSAN Senator, 7th National Assembly (2001-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ADAMAWA Party: SEN. TUKUR BELLO MOHAMMED Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ADAMAWA Party: SEN. ETOK ALOYSIUS AKPAN Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: AKWA IBOM Party: SEN. ENANG ITA SOLOMON JAMES Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: AKWA IBOM Party: SEN. ESSUENE HELEN UDOAKAHA Senator, 7th National Assembly (20011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: AKWA IBOM Party: SEN. EMEKA JOHN OKEY Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) View My Senatorial District Page Political Peoples Democratic Party State: ANAMBRA Party: SEN. NGIGE CHRIS NWABUEZE Senator, 7th National Assembly (2011-2015) Dr.