Three Points of the Residential High-Rise: Designing for Social Connectivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Great Rivers Confidential Draft Draft

greatriverschicago.com OUR GREAT RIVERS CONFIDENTIAL DRAFT DRAFT A vision for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 2 Our Great Rivers: A vision for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers Letter from Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel 4 A report of Great Rivers Chicago, a project of the City of Chicago, Metropolitan Planning Council, Friends of the Chicago River, Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and Ross Barney Architects, through generous Letter from the Great Rivers Chicago team 5 support from ArcelorMittal, The Boeing Company, The Chicago Community Trust, The Richard H. Driehaus Foundation and The Joyce Foundation. Executive summary 6 Published August 2016. Printed in Chicago by Mission Press, Inc. The Vision 8 greatriverschicago.com Inviting 11 Productive 29 PARTNERS Living 45 Vision in action 61 CONFIDENTIAL Des Plaines 63 Ashland 65 Collateral Channel 67 Goose Island 69 FUNDERS Riverdale 71 DRAFT DRAFT Moving forward 72 Our Great Rivers 75 Glossary 76 ARCHITECTURAL CONSULTANT OUR GREAT RIVERS 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This vision and action agenda for the Chicago, Calumet and Des Plaines rivers was produced by the Metropolitan Planning RESOURCE GROUP METROPOLITAN PLANNING Council (MPC), in close partnership with the City of Chicago Office of the Mayor, Friends of the Chicago River and Chicago COUNCIL STAFF Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Margaret Frisbie, Friends of the Chicago River Brad McConnell, Chicago Dept. of Planning and Co-Chair Development Josh Ellis, Director The Great Rivers Chicago Leadership Commission, more than 100 focus groups and an online survey that Friends of the Chicago River brought people to the Aaron Koch, City of Chicago Office of the Mayor Peter Mulvaney, West Monroe Partners appointed by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, and a Resource more than 3,800 people responded to. -

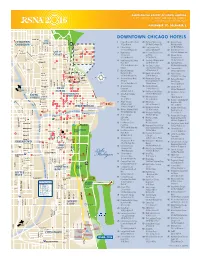

Hotel-Map.Pdf

RADIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA 102ND SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY AND ANNUAL MEETING McCORMICK PLACE, CHICAGO NOVEMBER 27 – DECEMBER 2 DOWNTOWN CHICAGO HOTELS OLD CLYBOURN 1 Palmer House Hilton Hotel 28 Fairmont Hotel Chicago 61 Monaco Chicago, CORRIDOR TOWN 17 East Monroe 200 North Columbus Dr. A Kimpton Hotel 2 Hilton Chicago 29 Four Seasons Hotel 225 North Wabash 23 720 South Michigan Ave. 120 East Delaware Pl. 62 Omni Chicago Hotel GOLD 60 70 3 Hyatt Regency 30 Freehand Chicago Hostel 676 North Michigan Ave. COAST 29 87 38 66 Chicago Hotel and Hotel 63 Palomar Chicago, 89 68 151 East Wacker Dr. 19 East Ohio St. A Kimpton Hotel 80 47 4 Hyatt Regency McCormick 31 The Gray, A Kimpton Hotel 505 North State St. Place Hotel 122 W. Monroe St. 64 Park Hyatt Hotel 2233 South Martin Luther 32 The Gwen, a Luxury 800 North Michigan Ave. King Dr. Collection Hotel, Chicago 65 Peninsula Hotel 5 Marriott Downtown 521 North Rush St. 108 East Superior St. 79 Magnificent Mile 33 Hampton Inn & Suites 66 Public Chicago 86 540 North Michigan Ave. 33 West Illinois St. 78 1301 North State Pkwy. Sheraton Chicago Hotel Hampton Inn Chicago 75 6 34 67 Radisson Blu Aqua & Towers Downtown Magnificent Mile 73 Hotel Chicago 301 East North Water St. 160 East Huron 221 N. Columbus Dr. 64 7 AC Hotel Chicago 35 Hampton Majestic 68 Raffaello Hotel NEAR 65 59 Downtown 22 West Monroe St. 201 East Delaware Pl. 62 10 34 42 630 North Rush St. NORTH 36 Hard Rock Hotel Chicago 69 Renaissance Chicago 46 21 MAGNIFICENT 230 North Michigan Ave. -

A Resort Style Community of Townhomes & Coach Homes

ARTIST RENDERING A RESORT STYLE COMMUNITY OF TOWNHOMES & COACH HOMES willowood folder for print.indd 1 3/23/17 3:10 PM BEYOND YOUR DREAMS ARTIST RENDERING Welcome to WillowWood at Overton Preserve, private gated community just steps from a 450-acre nature preserve. Here every amenity and convenience is found within your home with a maintenance-free resort lifestyle just outside your door. Brought to you by two legendary real estate names, Levitt House and The Klar Organization, whose decades of experience can be found in every detail. A new neighborhood of modern homes with superb design, WillowWood offers the very best of Long Island: spacious homes with thoughtful layouts, expansive natural open areas and a dedicated professional staff to handle all the exterior maintenance. Welcome Home. WITHIN YOUR REACH willowood folder for print.indd 2 3/23/17 3:10 PM ARTIST RENDERING WillowWood at Overton Preserve is at the midway point between New York City and Montauk, and equidistant between the Long Island Sound and the Great South Bay. In the 1700’s David Overton chose this spot to build a farmhouse and to raise a family. When the American War for Independence began, the area came under British military control and was used to store firearms and 300 tons of hay. A daring raid by patriot soldiers destroyed the British stockpile. Its been said the Overton’s youngest son, Nehemiah, was the first to set the hay on fire. Years later the Daughters of the Revolution set a plaque at the site commemorating the event. Today there are still remains of the original Overton farmhouse. -

Learning from Gated High-Rise Living. the Case Study of Changsha

Heaven Palace? Learning From Gated High-rise Living. The Case Study of Changsha Master Thesis 06/05/2014 Xiang Ding Nordic Program Sustainable Urban Transition Aalto University. School of Arts, Design and Architecture KTH University. School of Architecture and Built Environment Heaven Palace? Learning From Gated High-rise Living. The Case Study of Changsha Master Thesis 06/05/2014 Xiang Ding Nordic Program Sustainable Urban Transition Aalto University. School of Arts, Design and Architecture KTH University. School of Architecture and Built Environment © Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture & KTH University/ Xiang Ding / This publication has been produced during my scholarship period at Aalto University and KTH University. This thesis was produced at the Nordic Master Programme in Sustainable Urban Transitions for the Urban Laboratory II Master studio, A-36.3701 (5-10 cr). Research project: “ Learning From Gated High-rise Living. The Case Study of Changsha” Supervisor: Professor Kimmo Lapinitie from Aalto University / Professor Peter Brokking from KTH University. Course staff: Professor Kimmo Lapintie Post doc researcher Mina di Marino Architect Hossam Hewidy Dr Architect Helena Teräväinen Aalto University, Espoo, Finland 2014 2 Contents Contents List of Figures and Tables 4-7 Abstract 8 Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Gated Communities 10 1.2 High-rise Living 11 1.3 Residents’ Daily Lives 12 1.4 Learning From Nordic Cities 14 1.5 Research Design 16 Chapter 2 Context of China 2.1 Context of Ancient China 18 2.2 Context -

2021 Chicago Hotels

2021 PEI CONVENTION AT THE NACS SHOW - CHICAGO, IL - OCTOBER 5 - 8, 2021 2021 PEI HOTELS ARE INCDICATED IN RED 2021 CHICAGO HOTELS 1 21c Museum Hotel Chicago 23 Hotel EMC2, Autograph Collection 2 AC Hotel Chicago Downtown 24 Hyatt Centric Chicago Magnificent Mile 3 Allerton Warwick Hotel 25 Hyatt Place Chicago River 4 Aloft Chicago Downtown North River North 26 Hyatt Regency Chicago 44 5 Cambria Hotel Chicago 31 40 48 46 Loop 27 Hyatt Regency McCormick Place PEI HQ HOTEL 6 Chicago Marriott Downtown Magnificent Mile 28 InterContinental Chicago 3 15 21 Magnificent Mile 33 7 2 24 11 Courtyard Chicago 23 48 1 10 8 Downtown/River North 29 LondonHouse Chicago 6 32 18 4 28 9 8 25 12 Doubletree Chicago 30 Marriott Marquis Chicago 7 41 Magnificent Mile McCormick Place 37 39 22 29 26 9 Embassy Suites by Hilton 31 Millennium Knickerbocker 38 42 16 36 Chicago Downtown 13 35 Magnificent Mile 32 Moxy Chicago Downtown 5 10 Embassy Suites Chicago 33 Omni Chicago Hotel - An All Downtown Suite Property 45 34 11 Fairfield Inn & Suites 34 Palmer House Hilton Chicago Downtown/ Magnificent Mile 35 Radisson Blu Aqua Hotel Chicago 12 Fairfield Inn & Suites Chicago Downtown/ 36 Renaissance Chicago RiverNorth Downtown Hotel 13 Fairmont Chicago 37 Residence Inn Chicago 43 Millennium Park Downtown Magnificent Mile 17 14 Hampton Inn by Hilton 38 Residence Inn Chicago Chicago McCormick Place Downtown River North 15 Hampton Inn Chicago 39 Royal Sonesta Chicago Downtown Magnificent Mile Riverfront 16 Hampton Inn Chicago 40 Sheraton Grand Chicago Downtown/N Loop/ Michigan Ave 41 SpringHill Suites Chicago River North 17 Hilton Chicago 42 Swissôtel Chicago 18 Hilton Garden Inn 43 The Blackstone Hotel, 19 Hilton Garden Inn Chicago Autograph Collection McCormick Place 44 The Drake, a Hilton Hotel 20 Home 2 Suites by Hilton 31 Chicago McCormick Place 45 The Silversmith Hotel & 21 20 15 Suites 28 21 Homewood Suites by Hilton Chicago Magnificent Mile 46 The Talbott Hotel 22 Hotel Chicago, A Marriott 47 W Chicago Lakeshore Autograph Collection Hotel 48 Westin Michigan Avenue Chicago. -

Gated Communities and Their Role in China's Desire for Harmonious Cities

Hamama and Liu City Territ Archit (2020) 7:13 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-020-00122-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access What is beyond the edges? Gated communities and their role in China’s desire for harmonious cities Badiaa Hamama1* and Jian Liu2 Abstract During the rapid process of urbanization in post-reform China, cities assumed the role of a catalyst for economic growth and quantitative construction. In this context, territorially bounded and well delimited urban cells, glob- ally known as ‘gated communities’, xiaoqu, continued to defne the very essence of Chinese cities becoming the most attractive urban form for city planners, real estate developers, and citizens alike. Considering the guidelines in China’s National New Urbanization Plan (2014–2020), focusing on the promotion of humanistic and harmonious cities, in addition to the directive of 2016 by China’s Central Urban Work Conference to open up the gates and ban the construction of new enclosed residential compounds, this paper raises the following questions: As the matrix of the Chinese urban fabric, what would be the role of the gated communities in China’s desire for a human-qualitative urbanism? And How to rethink the gated communities to meet the new urban challenges? Seeking alternative per- spectives, this paper looks at the gated communities beyond the apparent limits they seem to represent, considering them not simply as the ‘cancer’ of Chinese cities, rather the container of the primary ingredients to reshape the urban fabric dominated by the gate. Keywords: Chinese gated community, Qualitative urbanism, Human-oriented approaches, Openness, Gatedness as opportunity Introduction and methodology and misinterpretations (Liu et al. -

Read More and Download The

Case Study: Vista Tower, Chicago A New View, and a New Gateway, for Chicago Abstract Upon completion, Vista Tower will become Chicago’s third tallest building, topping out the Lakeshore East development, where the Chicago River meets Lake Michigan. Juliane Wolf will participate in the Session 7C panel discussion High-Rise Occupying a highly visible site on a north- Design Drivers: Now to 2069, on Jeanne Gang Juliane Wolf south view corridor within the city’s grid, and in Wednesday, 30 October. Vista Tower is the subject of the off-site close proximity to the Loop, the river, and the program on Thursday, Authors city’s renowned lakefront park system, this 31 October. Jeanne Gang, Founding Principal and Partner Juliane Wolf, Design Principal and Partner mixed-use supertall building with a porous Studio Gang 1520 West Division Street base is simultaneously a distinctive landmark Chicago, IL 60642 USA at the scale of the city and a welcoming connector at the ground plane. Clad in a t: +1 773 384 1212 gradient of green-blue glass and supported by a reinforced concrete structure, the e: [email protected] studiogang.com tower is composed of an interconnected series of stacked, frustum-shaped volumes that move rhythmically in and out of plane and extend to various heights. The Jeanne Gang, architect and MacArthur Fellow, is the Founding Principal and Partner of Studio tower is lifted off the ground plane at the center, creating a key gateway for Gang, an architecture and urban design practice headquartered in Chicago with offices in New York, pedestrians accessing the Riverwalk from Lakeshore East Park. -

Downtown Chicago Hotels

107TH SCIENTIFIC ASSEMBLY AND ANNUAL MEETING November 28 to December 2 | McCormick Place, Chicago Downtown Chicago Hotels HQ Hyatt Regency McCormick Place Hotel Headquarters Hotel 41 51 2233 South Martin Luther King Drive 16 57 23 RSNA is proud to call Hyatt Regency McCormick Place Hotel its headquarter hotel for RSNA 2021. 1 21C Museum Hotel Chicago 28 Hotel Essex Chicago 53 2 AC Hotel Chicago Downtown 29 Hotel Julian 56 3 30 50 Allerton, a Warwick Hotel Hyatt Centric Chicago 48 4 ALOFT Chicago Mag Mile Magnificent Mile 31 Hyatt Regency Chicago Hotel 44 5 Best Western Grant Park Hotel 3 18 26 32 Hyatt Regency 42 6 The Blackstone Hotel 2 30 14 McCormick Place Hotel 9 7 13 1 33 4 11 Chicago Athletic Association Hotel 33 Inn of Chicago 22 25 39 8 Congress Plaza Hotel 17 34 12 34 10 InterContinental Hotel Chicago 37 9 Courtyard Chicago Downtown 35 27 49 Magnificent Mile JW Marriott 58 36 38 31 36 The Langham Chicago 52 10 Courtyard Chicago Downtown 46 59 45 54 15 River North 37 Loews Hotel Chicago 29 11 DoubleTree Hotel Chicago 38 LondonHouse Chicago Magnificent Mile 39 Marriott Downtown Magnificent Mile 12 47 7 Embassy Suites Chicago Downtown 40 Marriott Marquis Chicago 43 Magnificent Mile 55 41 Millennium Knickerbocker Hotel 35 13 Embassy Suites Hotel Chicago 42 Omni Chicago Hotel Downtown 43 Palmer House Hilton Hotell 14 Fairfield Inn and Suites Chicago 44 Peninsula Hotel 8 Downtown Magnificent Mile 15 45 Radisson Blu Aqua Hotel Chicago 6 Fairmont Hotel Chicago 20 16 Four Seasons Hotel 46 Renaissance Chicago Hotel 28 17 The Gwen, a Luxury -

Life Satisfaction of Downtown High-Rise Vs. Suburban Low-Rise Living: a Chicago Case Study

sustainability Article Life Satisfaction of Downtown High-Rise vs. Suburban Low-Rise Living: A Chicago Case Study Peng Du 1,*, Antony Wood 1, Nicole Ditchman 2 and Brent Stephens 3 1 College of Architecture, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL 60616, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Psychology, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL 60616, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Civil, Architectural, and Environmental Engineering, Illinois Institute of Technology, Chicago, IL 60616, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-312-283-5646 Received: 14 April 2017; Accepted: 14 June 2017; Published: 17 June 2017 Abstract: There has been a long-standing debate about whether urban living is more or less sustainable than suburban living, and quality of life (QoL) is one of several key measures of the social sustainability of residential living. However, to our knowledge, no study to date has examined life satisfaction among residents of downtown high-rise living compared to residents living in suburban low-rise housing. Further, very few studies have utilized building or neighborhood-scale data sets to evaluate residents’ life satisfaction, and even fewer have controlled for both individual and household-level variables such as gender, age, household size, annual income, and length of residence, to evaluate residents’ life satisfaction across different living scenarios. Therefore, the goal of this study was to investigate residents’ satisfaction with their place of residence as well as overall life in general via surveys of individuals living in existing high-rise residential buildings in downtown Chicago, IL, and in existing low-rise residential buildings in suburban Oak Park, IL. -

Gated Communities Are Residential Areas with Restricted Access Such That Normally Public Spaces Have Been Privatized

“Divided We Fall: Gated and Walled Communities in the United States” by Edward J. Blakely and Mary Gail Snyder from: Blakely, Edward J., and Mary Gail Snyder. “Divided We Fall: Gated and Walled Communities in the United States.” Architecture of Fear. Nan Ellin, ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997. The Gating of the American Mind It has been over three decades since this nation legally outlawed all forms of discrimination in housing, education, public transportation, and public accommodations. Yet today, we are seeing a new form of discrimination—the gated, walled, private community. Americans are electing to live behind walls with active security mechanisms to prevent intrusion into their private domains. Increasingly, a frightened middle class that moved to escape school integration and to secure appreciating housing values now must move to maintain their economic advantage. The American middle class is forting up. Gated communities are residential areas with restricted access such that normally public spaces have been privatized. These developments are both new suburban developments and older inner- city areas retrofitted to provide security. We are not discussing apartment buildings with guards or doormen. In essence, we are interested in the newest form of fortified community that places security and protection as its primary feature. We estimate that eight million1 and potentially many more Americans are seeking this new refuge from the problems of urbanization. Economic segregation is scarcely new. In fact, zoning and city planning were designed in part to preserve the position of the privileged by subtle variances in building and density codes. But the gated communities go further in several respects: they create physical barriers to access, and they privatize community space, not merely individual space. -

Determinants of the Development of Gated Housing Estates in Mombasa and Kilifi Counties, Kenya

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2015, PP 124-132 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Determinants of the Development of Gated Housing Estates in Mombasa and Kilifi Counties, Kenya Wambua Paul, Theuri Fridah (PhD) Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: This study intended to determine factors responsible for the strategic development of gated communities with specific focus on Mombasa and Mtwapa in Mombasa and Kilifi counties in Kenya. The study sought to establish the extent to which security, real estate speculation, status/lifestyle or strategic location influences development of gated housing units. A descriptive survey study of residents, real estate investors and real estate professionals was designed to help provide data to seal the existing research gap by assessing the contributions of each of the factors. A total of 253 respondents who were sampled from the target population using both stratified and purposive sampling methods returned 240 useful fully filled questionnaires and 13 interview instruments. Data obtained was analysed both qualitatively and quantitatively. Qualitative data was analysed using content analysis while for quantitative data; descriptive and inferential methods were used with the aid of Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 computer software. Specifically, descriptive statistics in the form of frequencies, percentages, -

July 2021 Affordable Housing Opportunities

JULY 2021 Affordable and Low-Income Housing Opportunities for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities ALAMEDA COUNTY PROPERTY TYPE OF UNITS / RENT ELIGIBILITY ACCESSIBILITY / AMENITIES HOW TO APPLY? 1475 167th Avenue (11) 1-BR: $1,221-$1,478/mo Minimum income: Accessibility: Accessible path UNITS AVAILABLE 1475 167th Ave. $2,442/mo throughout entire property, pool lift, San Leandro, CA 94578 *No age requirement ADA units Apply online Alameda County Maximum income: Housing Portal or print/send Mercy Housing *Section 8 accepted 1 person: $4,795/mo Amenities: Clubhouse with meeting application to Mercy Housing. Property Manager: Laura 2 persons: $5,480/mo room, community pool, outdoor BBQ (510) 962-8120 area, on-site laundry Application Deadline: [email protected] July 6, 2021 at 5:00 PM Parking: Gated parking available Pets: Service animals only As of 6/30/2021 Utilities: Included St. Andrew’s Manor Studio: 30% Income Minimum income: Accessibility: ADA accessible units, WAITLIST OPEN 3250 San Pablo Ave. 1-BR: 30% Income n/a close to BART and AC Transit Oakland, CA 94608 Apply online SAHA Homes. *Senior Housing: +62yr Maximum income: Amenities: On-site supportive services SAHA Homes TBD and management, Flier attached here. Leasing Office: (833) 496-5295 *Project-Based Section 8 [email protected] Parking: Street parking Application Deadline: July 8, 2021 at 5:00 PM Pets: Service animals only Utilities: Included As of 6/30/2021 Page 1 JULY 2021 Affordable and Low-Income Housing Opportunities for Seniors and Adults with Disabilities ALAMEDA COUNTY Aurora (2) Studio: 30% Income Minimum income: Accessibility: ADA adaptable units UNITS AVAILABLE 657 W MacArthur Blvd.