An Empirical Analysis of Adverse Incentives Caused by Revenue Sharing Daniel A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Making Cincinnati the National Epicenter for Minority Business

2019-2020 Making Cincinnati the National Epicenter for Minority Business Development 2 – 2019-2020 Accelerator Annual Report Letter from the Chair Over the past couple of years, we have outlined a bold vision and strategic plan to grow the aggregate annual revenues of minority businesses in the region by $1 billion and subsequently create an incremental 3,500 jobs by year-end 2022. This bold vision and plan have galvanized regional and national stakeholders desiring to partner with us to not only accomplish something transformational for Greater Cincinnati, but something that might truly inform and transform this work across the nation. Our four key pillars to achieve these bold goals, which are to grow our existing portfolio firms, build a robust pipeline, attract larger-scale minority firms to the region, and create new minority firms via acquisition of mainstream businesses, have each enjoyed major developments over the past year, and have collectively served to further elevate and position the Minority Business Accelerator as a national best practice. Importantly, our bold plan and vision follow over a decade of exceptional work in the region to build larger-scale minority-owned businesses, which was perhaps best captured in a LendingTree.com report released early in 2019 that recognized Cincinnati among the top 10 metropolitan areas in the country where minority entrepreneurs are finding success. Moreover, certain categories of that very same report, namely the percentage of minority-owned businesses in operation for more than the six years, as well as the percentage of minority businesses with annual revenues greater than $500K, rank Cincinnati as number one in the nation. -

BUSINESS Police Brace for Riots at Mass Funeral

M - MANCHESTER HERALD, Monday, July 22, 19B5 MANCHESTER U.S./WORLD SPORTS WEATHER BUSINESS Buckland history Big gamble pays off Little League stars Clear, cool tonight; is long and tangled for treasure hunter sent to the sidelines sunny Wednesday Beware the quacks in the cancer business ... page 3| ... page 5 1 ... page 151 .., page 2 operators of well-run clinics with sophisticated fear their competition. • Although some are highly educated, if misguided Our increasing sophistication on health matters and equipment to the back-alley, snake-oil salesmen of scientists, many are uneducated or with degrees from cancer treatment is creating a new breed of cynical legend. Some even may be accredited members of the entrepreneurs to capitalize on these attitudes. These Your medical profession; physicians, nurses and medical obscure colleges. are cancer quacks who market worthless products • Their treatment methods are often secret, and social workers. and use scientific language that fools the most Money's How much is spent on phony cancer cures and they refuse consultation with reputable physicians or educated among us, treatments? No one knows exactly. But health cancer specialists, "The promotion of quack remedies for cancer is Worth quackery is now a $10 billion-a-year business, said a • Their records are scanty or non-existent, and MnmhmttY Mrralft hardly a new phenomenon," notes Dr. Irving J. they depend on stories about "cures" of various Sylvia Porter recent study by a House subcommittee on aging. The ____^1_________ I TiiAsHTuesday, flv/ .liilviJuly 23, 1985 — Single copy: 254 Lerner of the University of Minnesota in the American main targets of the frauds are cancer victims, individuals. -

Cincinnati Reds'

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings July 20, 2018 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 2000-Mike Bell’s major league debut makes the Bells the first three-generation family in big league history to play for one team. Mike’s grandfather, Gus, played for the Reds from 1953 to 1961 and his father, Buddy, played from 1985 to 1988 MLB.COM Riggleman talks managing Reds' turnaround By Bill Ladson MLB.com @ladsonbill24 Jul. 19th, 2018 In a recent phone interview with MLB.com, Reds interim manager Jim Riggleman answered questions on a wide range of topics, from his managerial style to his respect for Reds ownership. MLB.com: Your agent, Burton Rocks, told me you are having the time of your life. How much fun are you having? Jim Riggleman: I have to preface it by saying working with and for [former Reds manager] Bryan Price was great. I love Bryan. It was kind of like when I was with Manny [Acta in Washington]. They managed well. It's just that they couldn't win ballgames. After a while, that just catches up to you. The other side of that is, now that I've become the manager, I do, absolutely, love it. I'm enjoying it to the nth degree. It's what I love to do. MLB.com: Once you took over, what made the team click? Riggleman: I think a couple of things: After about a week into the season, Eugenio Suarez got hit by a pitch and broke a finger. He was out for about three weeks. And then right around the same time, Scott Schebler, our right fielder, had a shoulder issue, and we put him on the DL for a couple of weeks. -

Indianapolisindianapolis Usedused Sportssports Toto Growgrow Itsits Economyeconomy Andand Buildbuild Betterbetter Neighborhoodsneighborhoods

Winter 2011 SuperSuper City HowHow IndianapolisIndianapolis UsedUsed SportsSports toto GrowGrow ItsIts EconomyEconomy andand BuildBuild BetterBetter NeighborhoodsNeighborhoods AlsoAlso Inside:Inside: TheThe JerseyJersey EffectEffect HunterHunter SmithSmith HowHow TeddyTeddy RooseveltRoosevelt SavedSaved FootballFootball JohnJohn J.J. MillerMiller Winter 2011 AMERICAN OUTLOOK | 1 Rooting the Future in History Susan Stinn Please Visit Us at The Levey Mansion –Where Indianapolis’ Rich History Meets Today’s Most Important Conversations Perched at the corner of Meridian and 29th Streets in downtown Indianapolis, the historic Louis H. Levey Mansion serves as an ideal vantage point for Sagamore Institute to conduct its work as a think tank in America’s Heartland. Originally built in the early 20th century by Indianapolis businessman Louis H. Levey, the mansion remains an integral part of what is today known as Historic Square. The legacy began when Mr. Levey joined his illustrious neighbor, Charles W. Fairbanks, in hosting such luminaries as Fairbanks’ former boss, President Teddy Roosevelt. President Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt Louis H. Levey Charles W. Fairbanks Table of Contents 8 28 32 Cover Features 8 A Lasting Legacy—Indianapolis Style By Mark D. Miles and James Taylor 11 Q&A: Indianapolis Sports Strategy 14 Indianapolis- A Championship City The Playbook 17 Visionary Community Development Plan Earns Legacy Project By Bill Taft 20 Indianapolis’ R for Building a Better Community: Volunteers By Wesley Cate 24 From L.A. to Indy: NFL Charities Leaves a Lasting Legacy By Zoe Sandvig Erler Sports & Character 28 The Jersey Effect: Beyond the World Championship Ring By Hunter Smith 31 Uncommon: Finding Your Path to Significance By Tony Dungy 32 Passing Tradition 34 Tim Tebow’s Role Model By MicheaI Flaherty and Nathan Whitaker 4 | AMERICAN OUTLOOK www.americanoutlook.org OAmericanutlook Winter 2011 Vol. -

Nfl) Retirement System

S. HRG. 110–1177 OVERSIGHT OF THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE (NFL) RETIREMENT SYSTEM HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 18, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–327 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska, Vice Chairman JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARGARET L. CUMMISKY, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel LILA HARPER HELMS, Democratic Deputy Staff Director and Policy Director CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel PAUL NAGLE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on September 18, 2007 .................................................................... -

Cultural Affairs Bureau Lists 15 Elements of Intangible Heritage

SCIENCE CENTER THREE KILLED, 27 LABOR LAW REOPENS THIS WEEK INJURED IN HONG KONG CHANGES The center’s repair works, Three people were killed UNDER following the damage and 27 others injured when caused by Typhoon Hato, are a Hong Kong bus mounted a CONSULTATION still incomplete pavement P3 P5 P10 MON.25 Sep 2017 T. 25º/ 31º C H. 75/ 95% facebook.com/mdtimes + 11,000 MOP 7.50 2894 N.º HKD 9.50 FOUNDER & PUBLISHER Kowie Geldenhuys EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Paulo Coutinho www.macaudailytimes.com.mo “ THE TIMES THEY ARE A-CHANGIN’ ” WORLD BRIEFS AP PHOTO Foul play suspected P3 NORTH KOREA In a show of American in Lisboa Palace fire military might to North Korea, U.S. bombers and fighter escorts flew on Saturday to the farthest point north of the border between North and South Korea by any such American aircraft this century. The Pentagon said the mission in international airspace showed how seriously President Donald Trump takes North Korea’s “reckless behavior.” VIETNAM-PHILIPPINES Two fishermen were found dead and five others were taken into custody after they were spotted fishing off the northwestern Philippines, sparking a night chase where a Vietnamese boat hit a Philippine navy ship and prompted its crew to fire shots. AP PHOTO PHILIPPINES President Rodrigo Duterte says he became a local millionaire at a young age due to inheritance and reiterated he has no unexplained wealth as alleged by his leading critic, who questioned his claim that he was born into an impoverished family. INDONESIA More than 35,000 people have fled a menacing volcano on the Indonesian tourist island of Bali, fearing it will erupt for the first time in more than half a century as increasing tremors rattle Cultural Affairs Bureau lists 15 the region. -

Game Release

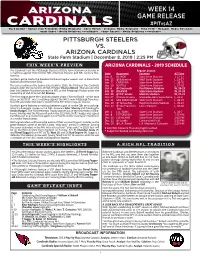

WEEK 14 GAME RELEASE #PITvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Re l ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med i a Rel ations Mik e He l m - Manag e r, Me d ia Rel ations I mani Sub e r - Me dia R e latio n s Coo rdinato r C hase Russe l l - M e dia Re latio ns Coor dinat or PITTSBURGH STEELERS VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS State Farm Stadium | December 8, 2019 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2019 SCHEDULE The Cardinals host the Pi sburgh Steelers at State Farm Stadium on Sunday in Regular Season a matchup against their former NFL American Division and NFL Century Divi- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time sion foe. Sep. 8 DETROIT State Farm Stadium T, 27-27 Sunday's game marks the Steelers third-ever regular season visit to State Farm Sep. 15 @ Bal more M&T Bank Stadium L, 23-17 Stadium and fi rst since 2011. Sep. 22 CAROLINA State Farm Stadium L, 38-20 The series between the teams dates back to 1933, the fi rst year the Cardinals Sep. 29 SEATTLE State Farm Stadium L, 27-10 played under the ownership of Hall of Famer Charles Bidwill. That was also the Oct. 6 @ Cincinna Paul Brown Stadium W, 26-23 year the Steelers franchise joined the NFL as the Pi sburgh Pirates under the Oct. 13 ATLANTA State Farm Stadium W, 34-33 ownership of Hall of Famer Art Rooney. Oct. 20 @ N.Y. Giants MetLife Stadium W, 27-21 The fi rst league game the Cardinals played under Charles Bidwill - which took Oct. -

Who Rules Cincinnati?

Who Rules Cincinnati? A Study of Cincinnati’s Economic Power Structure And its Impact on Communities and People By Dan La Botz Cincinnati Studies www.CincinnatiStudies.org Published by Cincinnati Studies www.CincinnatiStudies.org Copyright ©2008 by Dan La Botz Table of Contents Summary......................................................................................................... 1 Preface.............................................................................................................4 Introduction.................................................................................................... 7 Part I - Corporate Power in Cincinnati.........................................................15 Part II - Corporate Power in the Media and Politics.....................................44 Part III - Corporate Power, Social Classes, and Communities......................55 Part IV - Cincinnati: One Hundred Years of Corporate Power.....................69 Discussion..................................................................................................... 85 Bibliography.................................................................................................. 91 Acknowledgments.........................................................................................96 About the Author...........................................................................................97 Summary This investigation into Cincinnati’s power structure finds that a handful of national and multinational corporations dominate -

Sports Scandals from the Top-Down: Comparative Analysis of Management, Owner, and Athletic Discipline in the NFL & NBA

Volume 23 Issue 1 Article 2 4-1-2016 Sports Scandals from the Top-Down: Comparative Analysis of Management, Owner, and Athletic Discipline in the NFL & NBA Joshua S.E. Lee Jaimie K. McFarlin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Labor and Employment Law Commons Recommended Citation Joshua S. Lee & Jaimie K. McFarlin, Sports Scandals from the Top-Down: Comparative Analysis of Management, Owner, and Athletic Discipline in the NFL & NBA, 23 Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports L.J. 69 (2016). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/mslj/vol23/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jeffrey S. Moorad Sports Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Lee and McFarlin: Sports Scandals from the Top-Down: Comparative Analysis of Manage SPORTS SCANDALS FROM THE TOP-DOWN: COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF MANAGEMENT, OWNER, AND ATHLETIC DISCIPLINE IN THE NFL & NBA JOSHUA S.E. LEE* & JAIMIE K. MCFARLIN** This article serves to discuss the current landscape of professional sports discipline and commissioner power in the NFL & NBA, specifically under- standing the discipline of management and ownership in the major leagues as compared to player discipline when franchise ownership interests and commissioner power conflict. Furthermore, these particular events illuminate the differences between discipline in professional sports and non-sports contexts. I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 70 II. THE PROFESSIONAL SPORTS LABOR SYSTEM AND PLAYER DISCIPLINE .......................................... -

Cincinnati Reds'

CCIINNCCIINNNNAATTII RREEDDSS PPRREESSSS CCLLIIPPPPIINNGGSS NOVEMBER 14, 2014 CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Cueto-for-Upton trade proposed by Sports on Earth writer David Clark Johnny Cueto for Justin Upton? It's one of five blockbuster trades that make sense, according to sportsonearth.com's Anthony Castrovince. From Castrovince: Neither of these clubs has the financial flexibility to be a major player in free agency, so here's a way for each of them to significantly address a pressing need in the trading game. Granted, I don't actually expect the Reds to move their ace in advance of a season in which they expect to contend. Walt Jocketty has made it pretty clear that's not his intent at all. Nor am I convinced John Hart will move his cleanup hitter, though he hinted this week that this is a stronger possibility than those rumors of him moving Evan Gattis. What I do know is that both Upton and Cueto are eligible for free agency next winter, and the odds of either remaining with his current club beyond 2015 seem slim, given the other contractual commitments their clubs have made. If either is to be moved, the best option might be to move them for pieces of immediate impact. The Reds need a productive left fielder who can get on base -- preferably in a short-term situation, before prospect Jesse Winker arrives (as soon as 2016). Upton runs notoriously hot and cold, but he's averaged 24 homers with a .357 OBP the last six seasons. He'd instantly augment and balance the heart of a lineup in which Joey Votto's knee woes and Jay Bruce's disappointing '14 are big concerns moving forward. -

2018 National Football League Committees As of October 4, 2018

2018 National Football League Committees As of October 4, 2018 Football Operations Competition Committee Rich McKay (Chairman) John Elway Stephen Jones John Mara Mark Murphy Ozzie Newsome Sean Payton Mike Tomlin Coaches Subcommittee John Madden (Chairman) Todd Bowles Jason Garrett John Harbaugh Mike McCarthy Bill O’Brien Andy Reid Ron Rivera Mike Zimmer General Managers Advisory Committee Rick Spielman (Co-Chairman) Tom Telesco (Co-Chairman) David Caldwell Kevin Colbert Thomas Dimitroff Mickey Loomis Reggie McKenzie Mike Maccagnan Will McClay John Schneider Subcommittee on College Relations John Schneider (Chairman) Chris Grier Steve Keim Mark Murphy Jon Robinson Mike Tomlin Doug Williams Player Safety Advisory Panel John Madden (Co-Chairman) Ronnie Lott (Co-Chairman) Patrick Kerney Willie Lanier Steve Mariucci Curtis Martin Mark Murphy* Orlando Pace *Liaison to owners H&S Advisory Committee Health & Safety Health & Safety Advisory Committee John York (Chairman) Charlotte Anderson Michael Bidwill Shahid Khan Rich McKay John Mara Mark Murphy Terry Pegula Art Rooney II David Tepper 2 Health & Safety Medical Committee Dr. Elliott Hershman (Chair) Drs. Robert Anderson & Ed Wojtys (Musculoskeletal Committee) James Collins (PFATS President) Dr. Rob Heyer (NFLPS President) Dr. Thom Mayer (NFLPA) Dr. Andrew Tucker (General Medical Committee) Dr. John York (Owners’ Health & Safety Advisory Committee) League Consultants Drs. Lawrence Brown & John Lombardo (Drug Policy Advisors) Drs. Jeff Crandall & Rich Kent (Engineering Consultants) Drs. Nancy Dryer & Christina Mack (Quintiles) General Medical Committee Dr. Andrew Tucker (Chairman) Dr. Deverick Anderson Rick Burkholder Dr. Doug Casa Dr. Rob Heyer Dwight Hollier Dr. Thom Mayer (NFLPA) Dr. Patrick Strollo Dr. Robert Vogel Head, Neck and Spine Committee Dr. -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1919-The Reds hire Pat Moran as manager, replacing Christy Mathewson, when no word is received from him while his is in France with the U.S. Army. Moran would manage the Reds until 1923, collecting a 425-329 record 1978-Former Reds executive, Larry MacPhail, is elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 1997-The Reds sign Deion Sanders to a free agent contract, for the second time ESPN.COM Busy Reds in on Realmuto, but would he make them a contender? Jan. 29, 2019 Buster Olney ESPN Senior Writer The last time the Cincinnati Reds won a postseason series, Joey Votto was 12 years old, Bret Boone was the team's second baseman and the organization had only recently drafted his kid brother, a third baseman out of the University of Southern California named Aaron Boone. Since the Reds swept the Dodgers in a Division Series in 1995, they have built more statues than they have playoff wins. In recent years, a Dodger said he was sick of Kirk Gibson -- not because of anything Gibson had done, but because the team had felt the need to roll out the highlight of Gibson's epic '88 World Series home run, in lieu of subsequent championship success. Similarly, most of the biggest stars in the Reds organization continue to be Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose and Tony Perez, as well as announcer Marty Brennaman, who recently announced he will retire after the upcoming season.