A Railway, a City, and the Public Regulation of Private Property: CPR V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vancouver Early Years Program

Early Years Programs The following is a list of Early Years Programs (EYP) in the City of Vancouver. These programs offer drop-in sessions or registered programs for families to attend with young children. These programs include: A. Community Centres: A variety of programs available for registration for families and children of all ages. B. Family Places: Programs offered include drop-ins for parents, caregivers and children, peer counseling, prenatal programs, clothing exchanges, community kitchens and nutrition education. C. Neighourhood Houses: Various programs offered for all children and families, including newcomers, such as literacy, family resource programs, childcare and much more. D. Strong Start Programs: StrongStart is a free drop-in program in some Vancouver schools that is offered to parents and caregivers with children ages zero to five years old. You must register to attend. Visit Vancouver School Board website for registration information www.vsb.bc.ca/Student_Learning/Early-Learners/StrongStart. E. Vancouver Public Libraries: Public libraries are located around the City. Many programs, such as story times are offered for children, families and caregivers. Visit www.vpl.ca for hours, programs and locations. October 2018 Westcoast Child Care Resource Centre www.wccrc.ca| www.wstcoast.org A. Community Centres Centre Name Address Phone Neighourhood Website Number Britannia 1661 Napier 604-718-5800 Grandview- www.brittnniacentre.org Woodland Champlain Heights 3350 Maquinna 604-718-6575 Killarney www.champlainheightscc.ca -

Summary 2019

Our work 2019 www.heritagevancouver.org | December 2019 www.heritagevancouver.org | December 2019 To the members & donors of Heritage Vancouver We are growing, more historic buildings important, but it’s become clear that what makes the retail of Mount focused, and dedicated Pleasant Mount Pleasant is also tied to things like small local businesses, affordable rents, to creating a diverse and the nature of lot ownership, the range of inspiring future for city. demographic mix, and the diversity in the types of shops and services. In our experience, there is a view that heritage In last year’s letter, I discussed some of the has shifted to intangible heritage versus best practice approaches starting to make its tangible heritage. way into local heritage and into the upcoming The dichotomy between intangible heritage planned update to the City of Vancouver’s and tangible heritage certainly does exist. aging heritage conservation program. But it is important to point out that this Meanwhile, the City of Vancouver’s new dichotomy was introduced in the heritage field Culture plan Culture|Shift: Blanketing the as a corrective to include the things that the city in arts and culture includes a large focus protection of great buildings did not protect or on intangible heritage, reconciliation, and recognize. culture. While what all this will look like in What may be more useful for us is that heritage policy still isn’t completely clear, what we begin to care for the interrelationships is clear is that heritage in Vancouver is and will between things that are built, and the human be undergoing great change. -

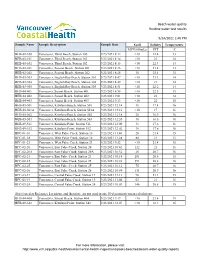

Beach Water Quality Routine Water Test Results 9/3/2021 1:05 PM

Beach water quality Routine water test results 9/24/2021 1:46 PM Sample Name Sample Description Sample Date Ecoli Salinity Temperature MPN/100mLs PPT °C BEB-01-100 Vancouver, Third Beach, Station 100 9/23/2021 8:12 <10 22.4 13 BEB-01-101 Vancouver, Third Beach, Station 101 9/23/2021 8:14 <10 23 14 BEB-01-102 Vancouver, Third Beach, Station 102 9/23/2021 8:16 <10 22.4 14 BEB-02-201 Vancouver, Second Beach, Station 201 9/23/2021 8:26 <10 23.4 13 BEB-02-202 Vancouver, Second Beach, Station 202 9/23/2021 8:28 10 25.3 13 BEB-03-303 Vancouver, English Bay Beach, Station 303 9/23/2021 8:47 <10 21.3 14 BEB-03-304 Vancouver, English Bay Beach, Station 304 9/23/2021 8:49 <10 21 14 BEB-03-305 Vancouver, English Bay Beach, Station 305 9/23/2021 8:51 <10 22.2 14 BEB-04-401 Vancouver, Sunset Beach, Station 401 9/23/2021 8:58 <10 22.5 15 BEB-04-402 Vancouver, Sunset Beach, Station 402 9/23/2021 9:01 <10 22 14 BEB-04-403 Vancouver, Sunset Beach, Station 403 9/23/2021 9:13 <10 22 15 BEB-05-501 Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 501 9/23/2021 12:14 10 17.4 16 BEB-05-501A Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 501A 9/23/2021 12:16 <10 17 16 BEB-05-502 Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 502 9/23/2021 12:18 20 16.9 16 BEB-05-503 Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 503 9/23/2021 12:20 10 16.6 16 BEB-09-511 Vancouver, Kitsilano Point, Station 511 9/23/2021 12:00 31 17.6 16 BEB-09-512 Vancouver, Kitsilano Point, Station 512 9/23/2021 12:02 10 17.6 16 BFC-01-16 Vancouver, West False Creek, Station 16 9/23/2021 11:46 20 21.4 15 BFC-01-18 Vancouver, West False Creek, -

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver J EAN BARMAN1 anada has become increasingly urban. More and more people choose to live in cities and towns. Under a fifth did so in 1871, according to the first census to be held after Canada C 1867 1901 was formed in . The proportion surpassed a third by , was over half by 1951, and reached 80 percent by 2001.2 Urbanization has not benefited Canadians in equal measure. The most adversely affected have been indigenous peoples. Two reasons intersect: first, the reserves confining those deemed to be status Indians are scattered across the country, meaning lives are increasingly isolated from a fairly concentrated urban mainstream; and second, the handful of reserves in more densely populated areas early on became coveted by newcomers, who sought to wrest them away by licit or illicit means. The pressure became so great that in 1911 the federal government passed legislation making it possible to do so. This article focuses on the second of these two reasons. The city we know as Vancouver is a relatively late creation, originating in 1886 as the western terminus of the transcontinental rail line. Until then, Burrard Inlet, on whose south shore Vancouver sits, was home to a handful of newcomers alongside Squamish and Musqueam peoples who used the area’s resources for sustenance. A hundred and twenty years later, apart from the hidden-away Musqueam Reserve, that indigenous presence has disappeared. 1 This article originated as a paper presented to the Canadian Historical Association, May 2007. I am grateful to all those who commented on it and to Robert A.J. -

Southeast False Creek

Southeast False Creek SCHEDULE A CITY OF VANCOUVER SOUTHEAST FALSE CREEK OFFICIAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN City of Vancouver SEFC Official Development Plan By-laws 1 April 2007 Southeast False Creek TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 INTERPRETATION 1.1 Definitions 1.2 Imported definitions 1.3 Incorporation by reference 1.4 Table of contents and headings 1.5 ODP provisions 1.6 Figures 1.7 Financial implications 1.8 Severability SECTION 2 PRINCIPLES GOVERNING DEVELOPMENT 2.1 Urban design principles 2.2 Sustainability principles SECTION 3 SUSTAINABILITY STRATEGIES 3.1 Environmental sustainability 3.2 Social sustainability 3.3 Economic sustainability 3.4 Maintaining the vision SECTION 4 LAND USE 4.1 Land use objective 4.2 Density 4.3 Specific land uses and regulations 4.4 Phasing of parks and community facilities 4.5 Shoreline SECTION 5 DEVELOPMENT REGULATIONS AND PATTERNS 5.1 Building regulation 5.2 Development patterns 5.3 Movement system 5.4 Areas City of Vancouver SEFC Official Development Plan By-laws 2 April 2007 Southeast False Creek SECTION 6 ILLUSTRATIVE PLANS Figure 1: SEFC Boundaries Figure 2: Areas Figure 3: Conceptual Strategy Figure 4: Figure 4 has been replaced by Table 1 in section 4 Figure 5: Retail/Service/Office/Light Industrial Figure 6: Cultural/Recreational/Institutional Figure 7: Parks Figure 8: Shoreline Concept Figure 9: Maximum Heights Figure 10: Optimum Heights Figure 11: Views Figure 12: Pedestrian Routes Figure 13: Bikeways Figure 14: Transit Figure 15: Street Hierarchy Figure 16: Illustrative Plan Figure 17: Illustrative Plan -

Intergovernment and Finance Committee Federal Gas Tax Task Force

GREATER VANCOUVER REGIONAL DISTRICT INTERGOVERNMENT AND FINANCE COMMITTEE FEDERAL GAS TAX TASK FORCE REGULAR MEETING Friday, May 29, 2015 9:00 a.m. 2nd Floor Boardroom, 4330 Kingsway, Burnaby, British Columbia R E V I S E D A G E N D A1 1. ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA 1.1 May 29, 2015 Regular Meeting Agenda That the Intergovernment and Finance Committee Federal Gas Tax Task Force adopt the agenda for its regular meeting scheduled for May 29, 2015 as circulated. 2. ADOPTION OF THE MINUTES 3. DELEGATIONS Added 3.1 Councillor Colleen Jordan, City of Burnaby 4. INVITED PRESENTATIONS 5. REPORTS FROM COMMITTEE OR STAFF 5.1 Overview of Gas Tax Funding Verbal Update Designated Speaker: Allan Neilson, General Manager, Planning, Policy and Environment 5.2 Process and Criteria for Approving TransLink Proposals for Funding Verbal Update Designated Speaker: Elisa Campbell, Director, Regional Planning, Planning, Policy and Environment 1 Note: Recommendation is shown under each item, where applicable. May 29, 2015 Intergovernment and Finance Committee Federal Gas Tax Task Force Regular Agenda May 29, 2015 Agenda Page 2 of 2 5.3 BC Transportation and Financing Authority Transit Assets and Liabilities Act (Bill 2) – Overview and Analysis That the GVRD Board receive for information the report dated May 24, 2015, titled “BC Transportation and Financing Authority Transit Assets and Liabilities Act (Bill 2) – Overview and Analysis”. 5.4 Ownership and Oversight of Regional Transportation Assets Funded through the Greater Vancouver Regional Fund That the GVRD Board: a) Receive for information the report dated May 20, 2015, titled “Ownership and Oversight of Regional Transportation Assets Funded through the Greater Vancouver Regional Fund”; and b) Direct staff to work with UBCM on structuring the Greater Vancouver Regional Fund Agreement to include a ten-year provision on the reinvestment of proceeds that are generated from the disposal of gas tax- funded assets. -

Fact Sheet 4

Planning & Urban Design Planning involves decisions about the use of land, resources, facilities and services in ways that support the physical, economic, and social well-being of our communities. In Vancouver, urban planning focuses on liveability. This means creating a city of neighbourhoods where all people can live, work and play. Planning often involves making difficult trade-offs, with the goal of creating urban environments where residents feel supported and engaged, and can enjoy safe, inclusive, and welcoming communities. Did You Know? The City of Vancouver is committed to making sure that neighbours In Vancouver, the are informed about “Vancouverism” is an authority to regulate land proposed internationally known use is granted by the developments in their term that combines deep Vancouver Charter. The neighbourhood, and respect for nature with Charter contains the rules that they have enthusiasm for busy, that govern how the City opportunities to engaging, active streets operates, what bylaws provide input. Visit and dynamic urban life City Council can create, www.shapeyourcity.ca and how budgets are set for updates on the latest community engagement opportunities One aspect of urban planning involves design. In Vancouver, the City aims to create high-quality urban design that contributes to an attractive, functional, inclusive, and safe city. Urban design is also reflected in parks and open spaces, sidewalks, walkways, bodies of water, trees and landscaping. Vancouver Plan Vancouver is a dynamic place, and over the current pandemic crisis, the Vancouver years our city has seen dramatic and Plan is shifting to respond to recovery continual change. While we have much to efforts. -

World-Leading Sustainable Tourism Destination Through Working Together to Achieve the Goals of the Greenest City 2020 Action Plan

Purpose To provide a policy and planning framework so tourism grows in a manner that is economically, socially and environmentally sustainable… … and thus able to meet the future needs of residents, visitors, investors and industry. Project A steering committee of the partners provided guidance to Resonance Consultancy who… o Surveyed 2,100+ Vancouverites o 50% from industry, 50% local residents o Received more than 11,000 comments o Conducted 180+ stakeholder interviews o Held 2 Open Houses o Reviewed more than 400 studies, reports & articles Tourism Master Plan Goals Experience - Visitors Provide compelling destination experiences that reflect the unique culture and diversity of Vancouver. Experience - Residents Ensure Vancouverites are engaged and committed hosts through a positive relationship between the tourism industry, visitors and local residents. Economics - Growth Lead key competitive cities in visitor spending growth that balances increased visitation with the integrity of the destination. Economics - Seasonality Deliver tourism experiences in low traffic months to help reduce seasonal fluctuations. Economics - Investment Expand private sector investment and coordinate public infrastructure spending to ensure a community-embraced tourism industry. Environment Become a world-leading sustainable tourism destination through working together to achieve the goals of the Greenest City 2020 Action Plan. Recommendations Recommendations Product Development Events Visitor Experience Design Neighbourhoods Tourism Infrastructure Development -

Media Relations

at your service your at Media Relations This primer sheet offers What We Can a quick snapshot of Do for You: the Granville Island Here at Granville Island, experience. our team is happy to help with your travel, tourism, Granville Island entertainment and culinary Nestled in the centre of feature stories. We can: Canada’s most beautiful city is a more than a market, more than • Offer interesting solid leads breathtaking island oasis that will to prepare stories first-hand. an entertainment district, more capture your heart and seduce your than an artists’ neighbourhood, • Provide contacts for senses. This gathering spot for more than a marina, more than a interviews. both locals and tourists draws 10.5 visitor attraction. It’s a thriving • Provide, digital images to million visitors each year (71% of community that pulses and hums supplement your story. Granville Island’s tourists are from with energy. outside of British Columbia). • Provide a specialized guide A couple of landmark years: More than a destination, Granville to show you Granville Island’s In 2004, the Granville Island Island is an urban haven spilling sights and sounds. Public Market celebrated its 25th over with fine restaurants, theatres, Anniversary. That same year, galleries and studios, and all things Hours of Operation the Island was named “Best fresh: seafood, fruit, vegetables, Neighbourhood” in North America Granville Island plants, flowers, candy, fudge, by Project for Public Spaces, a Public Market breads and baked treats. Bring New York-based non-profit agency. Open 7 days a week your appetite. Indulge in fresh, In 2002, it garnered a PPS award 9am to 7pm daily tantalizing fare from local clams of Merit when Great Markets and crab to a Mexican lunch. -

Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’S 2016 Media Kit

Assignment: Vancouver Tourism Vancouver’s 2016 Media Kit TABLE OF CONTENTS BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 4 WHERE IN THE WORLD IS VANCOUVER? ........................................................ 4 VANCOUVER’S TIMELINE.................................................................................... 4 POLITICALLY SPEAKING .................................................................................... 8 GREEN VANCOUVER ........................................................................................... 9 HONOURING VANCOUVER ............................................................................... 11 VANCOUVER: WHO’S COMING? ...................................................................... 12 GETTING HERE ................................................................................................... 13 GETTING AROUND ............................................................................................. 16 STAY VANCOUVER ............................................................................................ 21 ACCESSIBLE VANCOUVER .............................................................................. 21 DIVERSE VANCOUVER ...................................................................................... 22 WHERE TO GO ............................................................................................................... 28 VANCOUVER NEIGHBOURHOOD STORIES ................................................... -

False Creek South Community Profile PDF File

Marpole Community Plan FALSE CREEK SOUTH Community Profile 2017 FALSE CREEK SOUTH COMMUNITY PROFILE 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Introduction & Context 1 Demographics 8 Housing 20 Introduction False Creek South is a unique community known as one of Neighbourhood Character 33 Vancouver’s pioneering waterfront communities for inner city living. It represents the best planning practices of the 1970s Built Form and 1980s, and remains a thriving and sought-after community Amenities today. This Community Profile presents an overview of False Creek Transportation 39 South’s transformation, highlighting key aspects of the neighbourhood and its residents. The document is intended to provide a starting place for dialogue about the future of the neighbourhood, helping to inform the City’s discussion with the community on various issues that will be addressed through the neighbourhood planning process. Data used in this Profile is primarily from Statistics Canada, which conducts a census study every 5 years. INTRODUCTION & CONTEXT 1 FALSE CREEK SOUTH COMMUNITY PROFILE 2017 Study Area False Creek South Study Area Fairview Local Area FALSE CREEK SOUTH ROAWAY URRAR ST CAMIE ST FAIRVIEW 1TH AVE False Creek South is the area located between the Cambie lands) until it reaches the Burrard Bridge. The study area and Burrard Street bridges on the south shore of False Creek, represents 55 hectares (136 acres) of land and currently has a excluding Granville Island. The northern boundary of the study resident population of approximately 5,5971 people. area is the Creek. The southern boundary runs: west from Cambie Street along West 6th Avenue to Hemlock Street; northward along West 4th Avenue; and under the Granville Street Bridge to West 2nd Avenue. -

Vancouver Canada Public Transportation

Harbour N Lions Bay V B Eagle I P L E 2 A L A 5 A R C Scale 0 0 K G H P Legend Academy of E HandyDART Bus, SeaBus, SkyTrain Lost Property Customer Service Coast Express West Customer Information 604-488-8906 604-953-3333 o Vancouver TO HORSESHOE BAY E n Local Bus Routes Downtown Vancouver 123 123 123 i CHESTNUT g English Bay n l Stanley Park Music i AND LIONS BAY s t H & Vancouver Museum & Vancouver h L Anthropology Beach IONS B A A W BURRARD L Y AV BURRARD Park Museum of E B t A W Y 500 H 9.16.17. W 9 k 9 P Y a Lighthouse H.R.MacMillan G i 1 AVE E Vanier n Space Centre y r 3 AVE F N 1 44 Park O e s a B D o C E Park Link Transportation Major Road Network Limited Service Expo Line SkyTrain Exchange Transit Central Valley Greenway Central Valley Travel InfoCentre Travel Regular Route c Hospital Point of Interest Bike Locker Park & Ride Lot Peak Hour Route B-Line Route & Stop Bus/HOV Lane Bus Route Coast Express (WCE) West Millennium Line SkyTrain Shared Station SeaBus Route 4.7.84 A O E n Park 4 AVE 4 AVE l k C R N s H Observatory A E V E N O T 2 e S B University R L Caulfeild Columbia ta Of British Southam E 5 L e C C n CAULFEILD Gordon Memorial D 25 Park Morton L Gardens 9 T l a PINE 253.C12 .