Biliary Atresia 10 Gastroesophageal Reflux 14 Ключові Терміни: 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Value of 48- Or 72-Hr Urine Collections in Performing the Schilling Test

VALUE OF 48- OR 72-HR URINE COLLECTIONS IN PERFORMING THE SCHILLING TEST Edward B. Silberstein Radioisotope Laboratory, Cincinnati General Hospital, Cincinnati, Ohio In 21 % of 71 consecutive, normal Schilling serum vitamin B,2 levels less than 50 pg/mI, and tests evaluated in the Radioisotope Laboratory patients with abnormal vitamin B12 absorption as of the Cincinnati General Hospital, normal 57Co measured by a whole-body counter (6—10). cyanocobalamin excretion (greater than 8% of The test was performed, as previously described a test dose of 0.5 @g)was not achieved until 48— (5), with 0.5 @gof 57Co-cyanocobalamin, 1 @@Ci/ 72 hr. it is recommended that the vitamin B,2 @Lg;however, instead of a single day's collection, adsorption test, as described by Schilling, be serial 24-hr urines were collected for 48—72 hr with altered to routinely include at least a 48-hr additional “flushing―doses of 1 mg of cyanoco urine collection. balamin given intramuscularly at the beginning of the second and third days of the test. Each individual in this study produced at least 500 ml of urine per The Schilling test remains an important diagnos 24 hr with creatinine content exceeding 15 mg/kg tic procedure in the study of patients with megalo body weight if volume was under 500 ml to prove blastic anemia and/or peripheral neuropathy. In the that a full day's collection was made (1 1) . The 72-hr original description of the vitamin B,2 absorption collection was made if there was azotemia (BUN test by Schilling ( 1) , a 24-hr urine collection was exceeding 25 mg% ) or in any patient older than obtained after the oral administration of radioactive 65 years. -

Gastroenterostomy and Vagotomy for Chronic Duodenal Ulcer

Gut, 1969, 10, 366-374 Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.10.5.366 on 1 May 1969. Downloaded from Gastroenterostomy and vagotomy for chronic duodenal ulcer A. W. DELLIPIANI, I. B. MACLEOD1, J. W. W. THOMSON, AND A. A. SHIVAS From the Departments of Therapeutics, Clinical Surgery, and Pathology, The University ofEdinburgh The number of operative procedures currently in Kingdom answered a postal questionnaire. Eight had vogue in the management of chronic duodenal ulcer died since operation, and three could not be traced. The indicates that none has yet achieved definitive status. patients were questioned particularly with regard to Until recent years, partial gastrectomy was the eating capacity, dumping symptoms, vomiting, ulcer-type dyspepsia, diarrhoea or other change in bowel habit, and favoured operation, but an increasing awareness of a clinical assessment was made based on a modified its significant operative mortality and its metabolic Visick scale. The mean time since operation was 6-9 consequences, along with Dragstedt and Owen's years. demonstration of the effectiveness of vagotomy in Thirty-five patients from this group were admitted to reducing acid secretion (1943), has resulted in the hospital for a full investigation of gastrointestinal and widespread use of vagotomy and gastric drainage. related function two to seven years following their The success of duodenal ulcer surgery cannot be operation. Most were volunteers, but some were selected judged only on low stomal (or recurrent) ulceration because of definite complaints. There were more females rates; the other sequelae of gastric operations must than males (21 females and 14 males). The following be considered. -

The Reliability and Reproducibility of the Schilling Test in Primary Malabsorptive Disease and After Partial Gastrectomy

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.4.1.32 on 1 March 1963. Downloaded from Gut, 1963, 4, 32 The reliability and reproducibility of the Schilling test in primary malabsorptive disease and after partial gastrectomy J. F. ADAMS AND E. JUNE CARTWRIGHT From the Western Infirmary, Glasgow EDITORIAL SYNOPSIS A study of the reproducibility and reliability of the Schilling test in patients with primary malabsorptive disease and after partial gastrectomy is reported. The value of the test was assessed by repeated tests in each patient. Consistently normal or abnormal results were obtained in only one of the seven patients with primary malabsorptive disease and in only two of the eight patients who had undergone partial gastrectomy. From these results it is concluded that the result of a single test may be of little clinical value. Assessment of the results suggests that the mean value for a series of Schilling tests may give some indication of value clinically about the capacity to absorb radioactive vitamin B12 at the time of the tests at least in patients who have undergone partial gastrectomy. The significance of the findings is discussed, particularly in relation to the aetiology of post-gastrectomy megaloblastic anaemia. http://gut.bmj.com/ Absorption tests using radioactive vitamin B12 may ml. water; two hours later 1,000 ptg. vitamin B12 was given be of considerable value in establishing a precise intramuscularly and urine was collected for the subsequent diagnosis in conditions in which anaemia results 24 hours. The radioactivity in a 450 ml. aliquot was from malabsorption. It is obviously important to measured as described by Adams and Seaton (1961) and the total urinary radioactivity expressed as a percentage appreciate the limitations of such tests. -

A New Look at Vitaminb

A new look at vitaminB 18 The Nurse Practitioner • Vol. 34, No. 11 www.tnpj.com 2.5 CONTACT HOURS 12 deficiency By Sandra M. Nettina, APRN-BC, ANP, MSN ona Abraham is a 78-year-old widow who sees you for refill of her arthritis and antihypertensive med- M ications. She recently relocated from another state to be closer to her daughter, although she lives in her own “se- nior” apartment. Through history taking, you learn that she has a long history of osteoarthritis, mild hypertension requir- ing medication for the past 5 years, and occasional gastroe- sophageal reflux. Surgical history includes appendectomy as a teenager, a ventral hernia repair after her last child was born, and right knee arthroscopy about 5 years ago. Her medications include triamterene/hydrochlorthiazide 37.5/25 mg daily, acetaminophen 650 mg (2) twice daily , cal- cium citrate 600 mg/vitamin D 400 international units twice daily, omeprazole 20 mg daily p.r.n for heartburn, and hy- drocodone/acetaminophen 5/325 mg every 6h p.r.n. for severe pain. You perform a physical exam, discuss healthy diet and physical activity, order serum electrolytes and creatinine, refill her prescriptions, and advise her to schedule a follow-up ap- pointment in 3 months for preventative screening. You are about to conclude the visit and leave the room when Mrs. Abra- ham asks if she can get a vitamin B12 shot now. You question her about her need for B12 and Mrs. Abraham states she never knew how her previous primary care provider knew she had a vitamin B12 deficiency, but monthly shots have helped boost her energy over the past year. -

Effect of Prior Radiopharmaceutical Administration on Schilling Test Performance: Analysis and Recommendations

CASE REPORTS Effect of Prior Radiopharmaceutical Administration on Schilling Test Performance: Analysis and Recommendations Lionel S. Zuckier, Michael Stabin, Borys R. Krynyckyi, Pat Zanzonico and Barbara Binkert Department of Nuclear Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York; Radiation Internal Dose Information Center; Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, Oak Ridge, Tennessee; and the Department of Radiology, New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, New York, New York period in the Grampian Health Board Area in Scotland, inter Previously administered diagnostic and therapeutic radiopharma- ference by previously administered radiopharmaceuticals was ceuticals may interfere with performance of the Schilling test for suspected in five cases involving three radionuclides (67Ga and prolonged periods of time. Additionally, presence of confounding 75Se twice each; I3ll once) (3). radionuclides in the urine may not be suspected if baseline urine The International Committee for Standardization in Hema- measurements have not been performed before the examination. Methods: We assumed that a spurious contribution of counts tology has recommended that immediately before any B12 corresponding to 1% of the administered Schilling dose would absorption test, pretest baseline radioactivity measurements begin to contribute clinically significant interference. Based on the should be performed, such as a 12-hr control urine sample in the typical amounts of radiopharmaceuticals administered, spectra of case of the Schilling test (9). As supported by a recent survey of commonly used radionuclides and best available pharmacokinetic hospitals performing the dual-isotope Schilling test (8), it models of biodistribution and excretion, we estimated the interval appears that this time-consuming suggestion is not commonly required for 24-hr urinary excretion of diagnostic and therapeutic implemented and is recommended in only one (¡0) of three radiopharmaceuticals to drop below this threshold of significant interference. -

Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) Deficiency in Elderly Patients

Review Synthèse Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in elderly patients Emmanuel Andrès, Noureddine H. Loukili, Esther Noel, Georges Kaltenbach, Maher Ben Abdelgheni, Anne E. Perrin, Marie Noblet-Dick, Frédéric Maloisel, Jean-Louis Schlienger, Jean-Frédéric Blicklé Abstract and these should be excluded as causes of cobalamin defi- ciency before a diagnosis is made. To obtain cutoff points VITAMIN B12 OR COBALAMIN DEFICIENCY occurs frequently (> 20%) of cobalamin serum levels, patients with known complica- among elderly people, but it is often unrecognized because the tions are compared with age-matched control patients clinical manifestations are subtle; they are also potentially serious, without complications. Because different patient popula- particularly from a neuropsychiatric and hematological perspec- tions have been studied, several serum concentration defin- tive. Causes of the deficiency include, most frequently, food- itions have emerged.5–7 Varying test sensitivities and speci- cobalamin malabsorption syndrome (> 60% of all cases), perni- ficities result from the lack of a precise “gold standard.” cious anemia (15%–20% of all cases), insufficent dietary intake The definitions of cobalamin deficiency used in this review and malabsorption. Food-cobalamin malabsorption, which has are shown in Box 1. Based in part on the work of Klee7 and only recently been identified as a significant cause of cobalamin in part on our own work,8 they are calculated for elderly pa- deficiency among elderly people, is characterized by the inability to release cobalamin from food or a deficiency of intestinal cobal- tients. The first definition is simpler to interpret, but it re- amin transport proteins or both. We review the epidemiology and quires that blood samples be drawn on 2 separate days. -

Micronutrient Deficiencies As a Result of Bariatric Surgery

MICRONUTRIENT DEFICIENCIES AS A RESULT OF BARIATRIC SURGERY By Ashlie Lewis A Senior Project submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science in Nutrition Food Science and Nutrition Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, CA June 2010 ABSTRACT The most effective method of sustainable weight loss in obese patients is bariatric surgery. However, micronutrient deficiencies that can result after bariatric surgery can cause health problems that may outweigh its benefits. Micronutrient deficiencies are most common in patients who undergo Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch. The majority of vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies studies showed significant prevalence rates in their patient populations. Most concluded that routine oral B12 supplementation was ineffective at resolving deficiency; very high oral doses (> 350 µg) or intramuscular injections of crystalline B12 were typically required. Studies of iron deficiency after bariatric surgery found high prevalence rates due to inadequate oral supplementation, which can lead to the need for parenteral supplementation. Calcium and vitamin D deficiency studies also showed high prevalence rates of deficiency, which is important to address as deficiency can result in metabolic bone disease. Overall, the need for lifelong supplementation and follow up, early detection of deficiencies, patient education, and more aggressive supplementation regiments were emphasized to increase quality of life in bariatric surgery patients. Future research in bariatric surgery studies should include long-term health outcomes, patient education on required supplementation, and more aggressive supplementation regimens. Introduction Throughout the past several decades, prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States has steadily increased. -

Medical Grand Rounds Jejunoileal Bypass for The

I MEDICAL GRAND ROUNDS Southwestern Medical School Da 11 as, Texas JEJUNOILEAL BYPASS FOR THE TREATMENT OF OBESITY Peter Loeb, M.D. December 18, 1975 OUTLINE I. Introduction II. Obesity and Associated Disorders III. Medical Approach to Treatment of Obesity IV. Proposed Indications for Surgical Treatment of Morbid Obesity V. Intestinal Digestion and Absorption VI. Reserve and Regenerative Capacity of the Intestine VII. Surgically induced Malabsorption Jejunocolic Bypass for Obesity Partial Ileal Bypass for Hyperlipidemia Jejunoileal Bypass for Obesity Gastric Bypass for Obesity VIII. Surgical Complications of Jejunoileal Bypass IX. Benefits of Jejunoileal Bypass X. Medical Complications of Jejunoileal Bypass XI. Summary 1 I. Introduction The surgically-created intestinal bypass for the treatment of obesity is the most drastic and probably the mo st dangerous approach to the treatment of obesity yet devised by man. The justification for its application to selected patients whose weight vastly exceeds our present day no~ms is based on the following premises (1-4): Massive obesity is a "morbid" condition Other means of weight reduction are in large part unsuccessful The benefits of the currently utilized jejunoileal bypass procedures outweigh the complications of both the procedure itself and of the untreated "morbid" condition. The purpose of today 1 s discussion is to review briefly the first two premises and discuss in more detail the complications and so-cal led benefits associated with the jejunoileal bypass . II. Obes ity and Associated Disorders Obe sity is a condition in which there is an abnormal enlargement of adipose tissue, and is primarily a result of excessive food intake associated in part with decreased physical activity (5). -

Pernicious Anemia

PERNICIOUS ANEMIA Autoantibodies to intrinsic factor Intrinsic factor (IF), a sialic acid containing 60 kD glycoprotein, plays a vital role in the transport and absorption of vitamin B12 in the intestine. After secretion by parietal cells of the stomach mucosa IF binds to vitamin B12 ingested with food. This vitamin B12-IF complex is carried to the intestine where it allows absorbtion of vitamin B12 via binding to a specific IF receptor. Subsequently vitamin B12 is released into the blood binding to another protein (transcobalmin). Reduced production of the IF and / or impairment of its transport function in the digestive system bring about a deficiency in vitamin B12 leading to the development of pernicious anemia (Biermer`s anemia). Patients suffering from atrophic chronic gastritis of type A exhibit autoantibodies to both parietal cell H+/K+-ATPase and the intrinsic factor produced by parietal cells. According to their binding sites these autoantibodies are divided into two types. Type 1 antibody (blocking antibody) prevents the attachment of vitamin B12 to IF in the stomach. In contrary type 2 antibody (binding antibody) interacts with both IF and IF-vitamin B12 complex and prevents their absorption in the intestine by reacting with the IF region recognized by the mucosa. Etiopathogenesis of pernicious anemia Pernicious anemia is the result of chronic atrophic Neurological complications gastritis of type A. Contrary to gastritis type B this Peripheral neuropathy disease is an autoimmune process with a Demyelation, axonal degeneration and neuro- progressive destruction of the gastric mucosa. nal death Whilst type A gastritis involves the fundus and corpus of the stomach, type B gastritis affects the Sensory ataxia antrum as well and is usually associated with Memory loss Heliobacter pylori infections. -

Weight Loss Surgery and Nutrition

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT WEIGHT LOSS SURGERY AND NUTRITION Actor portrayal. WEIGHT LOSS SURGERY A BIG DECISION. A NEW LIFESTYLE. A NEW YOU. You may be thinking about having bariatric (weight This brochure will help you prepare for what to loss) surgery, or possibly already decided to have it. expect from weight loss surgery. Vitamin B12 is a You might feel a bit nervous, maybe even a little good example of this. Weight loss surgery can limit scared. But most of all, you probably feel hopeful. the amount of vitamin B12 that is absorbed in your body. It can be common to have vitamin B12 deficiency after surgery. It is important to know what vitamins and minerals you may need to take before and after surgery; what your nutritional needs will be; and what adjustments you may need to make to your lifestyle to help you stay healthy, including learning how to eat differently to get the nutrition your body needs. After having bariatric (weight loss) surgery, you may be closer to your goals than before - whether it is being healthy enough to keep up with the kids or just wanting to feel better. You will probably lose weight, which can help if you have weight-related conditions, such as: u Type 2 diabetes u Acid reflux u Sleep apnea u High cholesterol u High blood pressure Actor portrayal. 2 3 WHY VITAMINS AND MINERALS ARE IMPORTANT Before weight loss surgery, you may have taken in You may be wondering if you really need to take vitamins and minerals you needed from your diet. -

Measurement of Intestinal Absorption of 57Co Vitamin B12 by Serum Counting

J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.19.6.606 on 1 November 1966. Downloaded from J. clin. Path. (1966), 19, 606 Measurement of intestinal absorption of 57Co vitamin B12 by serum counting J. FORSHAW AND LILIAN HARWOOD From Sefton General Hospital, Liverpool SYNOPSIS The results of the measurement of vitamin B12 absorption by counting the radioactivity of 5 ml. serum obtained eight to 10 hours after the ingestion of an oral dose of 0 5 ,tg. vitamin B12 labelled with 0-5 ,uc. 57Co are compared with those obtained with the urinary excretion (Schilling) test. Inadequate urine collection and impaired renal function were responsible for low results in the Schilling test in four of the 12 control subjects, and an incomplete urine collection in four patients with pernicious anaemia could have led to doubt about the validity of the low result. The measurement of serum radioactivity for 1,000 seconds gave conclusive results, the range in the patients with malabsorption of vitamin B12 being between 0 and 24 counts per minute, and in the control subjects and other patients with megaloblastic anaemia between 28 and 64 counts per minute. The highest serum radioactivity level in a patient with pernicious anaemia was 19 counts per minute. Serum counting is simpler than the Schilling test and may be done alone when the patient's renal function is known to be poor, when urine collection is expected to be unreliable, or when the flushingcopyright. dose of vitamin B12 should be avoided. Otherwise there is an advantage in doing both tests together for confirmation. -

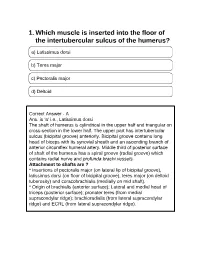

1. Which Muscle Is Inserted Into the Floor of the Intertubercular Sulcus of the Humerus?

1. Which muscle is inserted into the floor of the intertubercular sulcus of the humerus? a) Latissimus dorsi b) Teres major c) Pectoralis major d) Deltoid Correct Answer - A Ans. is 'a' i.e., Latissimus dorsi The shaft of humerus is cylindrical in the upper half and triangular on cross-section in the lower half. The upper part has intertubercular sulcus (bicipital groove) anteriorly. Bicipital groove contains long head of biceps with its synovial sheath and an ascending branch of anterior circumflex humeral artery. Middle third of posterior surface of shaft of the humerus has a spiral groove (radial groove) which contains radial nerve and profunda brachi vessels. Attachment to shafts are ? * Insertions of pectoralis major (on lateral lip of bicipital groove), latissimus dorsi (on floor of bicipital groove), teres major (on deltoid tuberosity) and coracobrachialis (medially on mid shaft). * Origin of brachialis (anterior surface); Lateral and medial head of triceps (posterior surface); pronater teres (from medial supracondylar ridge); brachioradialis (from lateral supracondylar ridge) and ECRL (from lateral supracondylar ridge). 2. At what level does the trachea bifurcates ? a) Upper border of T4 b) Lower border of T4 c) 27.5 cm from the incisors d) Lower border of T5 Correct Answer - B th Ans. is 'b' i.e., Lower border of T4 [Ref BDC S /e Volume 1 p. 267] Trachea bifurcates at carina, at the level of lower border of T, or T4 - T5 disc space. 3. Cricoid cartilage lies at which vertebral level ? a) C3 b) C6 c) T1 d) T4 Correct Answer - B Ans. is 'b' i.e., C6 [Ref BDC 5I'Ve Vol.