Storm Water Runoff Best Management Practices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Managing Storm Water Runoff to Prevent Contamination of Drinking Water

United States Office of Water EPA 816-F-01-020 Environmental Protection (4606) July 2001 Agency Source Water Protection Practices Bulletin Managing Storm Water Runoff to Prevent Contamination of Drinking Water Storm water runoff is rain or snow melt that flows off the land, from streets, roof tops, and lawns. The runoff carries sediment and contaminants with it to a surface water body or infiltrates through the soil to ground water. This fact sheet focuses on the management of runoff in urban environments; other fact sheets address management measures for other specific sources, such as pesticides, animal feeding operations, and vehicle washing. SOURCES OF STORM WATER RUNOFF Urban and suburban areas are predominated by impervious cover including pavements on roads, sidewalks, and parking lots; rooftops of buildings and other structures; and impaired pervious surfaces (compacted soils) such as dirt parking lots, walking paths, baseball fields and suburban lawns. During storms, rainwater flows across these impervious surfaces, mobilizing contaminants, and transporting them to water bodies. All of the activities that take place in urban and suburban areas contribute to the pollutant load of storm water runoff. Oil, gasoline, and automotive fluids drip from vehicles onto roads and parking lots. Storm water runoff from shopping malls and retail centers also contains hydrocarbons from automobiles. Landscaping by homeowners, around businesses, and on public grounds contributes sediments, pesticides, fertilizers, and nutrients to runoff. Construction of roads and buildings is another large contributor of sediment loads to waterways. In addition, any uncovered materials such as improperly stored hazardous substances (e.g., household Parking lot runoff cleaners, pool chemicals, or lawn care products), pet and wildlife wastes, and litter can be carried in runoff to streams or ground water. -

State Standard for Hydrologic Modeling Guidelines

ARIZONA DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES FLOOD MITIGATION SECTION State Standard For Hydrologic Modeling Guidelines Under the authority outlined in ARS 48-3605(A) the Director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources establishes the following standard for Hydrologic Modeling Guidelines in Arizona. State Standard for Hydrologic Modeling, or “guidelines for the experienced modeler”, has been developed to address hydrologic conditions for a variety of statewide watersheds. Included are problems and situations identified by the State Standard Work Group (SSWG) and floodplain managers. The intended audience is statewide; engineers, professionals and Floodplain Administrators. The following topics are included: • Hydrologic Model comparison and recommendation • Guidelines and parameters • Model application for specific situations, and associated hydrologic parameters • Precipitation values (NOAA 14) • Storm duration • Unique conditions, such as wildfire burn, overgrazing, logging, drought, rapid snowmelt, urbanization. The State Standard includes examples addressing the above key issues. This requirement is effective August, 2007. Copies of this State Standard and the State Standard Technical Supplement can be obtained by contacting the Department’s Water Engineering Section at (602) 771-8652. SS10-07 1 August 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction.......................................................................................................5 1.1 Purpose and Background .......................................................................5 -

Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture Safe Use of Safe Wastewater in Agriculture Proceedings No

A UN-Water project with the following members and partners: UNU-INWEH Proceedings of the UN-Water project on the Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture Safe Use of Wastewater in Agriculture Wastewater Safe of Use Proceedings No. 11 No. Proceedings | UNW-DPC Publication SeriesUNW-DPC Coordinated by the UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development (UNW-DPC) Editors: Jens Liebe, Reza Ardakanian Editors: Jens Liebe, Reza Ardakanian (UNW-DPC) Compiling Assistant: Henrik Bours (UNW-DPC) Graphic Design: Katja Cloud (UNW-DPC) Copy Editor: Lis Mullin Bernhardt (UNW-DPC) Cover Photo: Untited Nations University/UNW-DPC UN-Water Decade Programme on Capacity Development (UNW-DPC) United Nations University UN Campus Platz der Vereinten Nationen 1 53113 Bonn Germany Tel +49-228-815-0652 Fax +49-228-815-0655 www.unwater.unu.edu [email protected] All rights reserved. Publication does not imply endorsement. This publication was printed and bound in Germany on FSC certified paper. Proceedings Series No. 11 Published by UNW-DPC, Bonn, Germany August 2013 © UNW-DPC, 2013 Disclaimer The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the agencies cooperating in this project. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the UN, UNW-DPC or UNU concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise indicated, the ideas and opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent the views of their employers. -

The Causes of Urban Stormwater Pollution

THE CAUSES OF URBAN STORMWATER POLLUTION Some Things To Think About Runoff pollution occurs every time rain or snowmelt flows across the ground and picks up contaminants. It occurs on farms or other agricultural sites, where the water carries away fertilizers, pesticides, and sediment from cropland or pastureland. It occurs during forestry operations (particularly along timber roads), where the water carries away sediment, and the nutrients and other materials associated with that sediment, from land which no longer has enough living vegetation to hold soil in place. This information, however, focuses on runoff pollution from developed areas, which occurs when stormwater carries away a wide variety of contaminants as it runs across rooftops, roads, parking lots, baseball diamonds, construction sites, golf courses, lawns, and other surfaces in our City. The oily sheen on rainwater in roadside gutters is but one common example of urban runoff pollution. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) now considers pollution from all diffuse sources, including urban stormwater pollution, to be the most important source of contamination in our nation's waters. 1 While polluted runoff from agricultural sources may be an even more important source of water pollution than urban runoff, urban runoff is still a critical source of contamination, particularly for waters near cities -- and thus near most people. EPA ranks urban runoff and storm-sewer discharges as the second most prevalent source of water quality impairment in our nation's estuaries, and the fourth most prevalent source of impairment of our lakes. Most of the U.S. population lives in urban and coastal areas where the water resources are highly vulnerable to and are often severely degraded by urban runoff. -

SHETRAN and HEC HMS Model Evaluation for Runoff and Soil Moisture Simulation in the Jiˇcinkariver Catchment (Czech Republic)

water Article SHETRAN and HEC HMS Model Evaluation for Runoff and Soil Moisture Simulation in the JiˇcinkaRiver Catchment (Czech Republic) Vesna Ðuki´c* and Ranka Eri´c Faculty of Forestry, Department of Ecological Engineering for Soil and Water Resources, Protection University of Belgrade, Kneza VIšeslava 1, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +381-60-367-4549 Abstract: Due to the improvement of computation power, in recent decades considerable progress has been made in the development of complex hydrological models. On the other hand, simple conceptual models have also been advanced. Previous studies on rainfall–runoff models have shown that model performance depends very much on the model structure. The purpose of this study is to determine whether the use of a complex hydrological model leads to more accurate results or not and to analyze whether some model structures are more efficient than others. Different configurations of the two models of different complexity, the Système Hydrologique Européen TRANsport (SHETRAN) and Hydrologic Modeling System (HEC-HMS), were compared and evaluated in simulating flash flood runoff for the small (75.9 km2) JiˇcinkaRiver catchment in the Czech Republic. The two models were compared with respect to runoff simulations at the catchment outlet and soil moisture simulations within the catchment. The results indicate that the more complex SHETRAN model outperforms Citation: Ðuki´c,V.; Eri´c,R. the simpler HEC HMS model in case of runoff, but not for soil moisture. It can be concluded that SHETRAN and HEC HMS Model the models with higher complexity do not necessarily provide better model performance, and that Evaluation for Runoff and Soil the reliability of hydrological model simulations can vary depending on the hydrological variable Moisture Simulation in the Jiˇcinka under consideration. -

1.3 Wastewater and Ambient Water Quality · Understand the Quality, Quantity, Frequency and Sources of Applicability and Approach

General EHS Guidelines [Complete version] at: www.ifc.org/ehsguidelines Environmental, Health, and Safety (EHS) Guidelines GENERAL EHS GUIDELINES: ENVIRONMENTAL WASTEWATER AND AMBIENT WATER QUALITY WORLD BANK GROUP 1.3 Wastewater and Ambient Water Quality · Understand the quality, quantity, frequency and sources of Applicability and Approach......................................25 liquid effluents in its installations. This includes knowledge General Liquid Effluent Quality.......................................26 about the locations, routes and integrity of internal drainage Discharge to Surface Water....................................26 Discharge to Sanitary Sewer Systems.....................26 systems and discharge points Land Application of Treated Effluent........................27 · Plan and implement the segregation of liquid effluents Septic Systems ......................................................27 principally along industrial, utility, sanitary, and stormwater Wastewater Management...............................................27 Industrial Wastewater .............................................27 categories, in order to limit the volume of water requiring Sanitary Wastewater ..............................................29 specialized treatment. Characteristics of individual streams Emissions from Wastewater Treatment Operations .30 may also be used for source segregation. Residuals from Wastewater Treatment Operations..30 Occupational Health and Safety Issues in Wastewater · Identify opportunities to prevent or reduce -

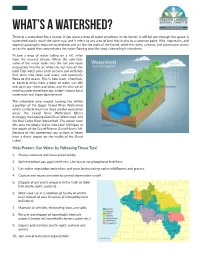

What's a Watershed?

What’s a Watershed? Think of a watershed like a funnel. If you place a drop of water anywhere in the funnel, it will fall out through the spout. A watershed works much the same way, and it refers to any area of land that drains to a common point. Hills, mountains, and sloping topography separate watersheds and act like the walls of the funnel, while the rivers, streams, and stormwater drains act as the spout that concentrates the water flowing over the land, channeling it elsewhere. Picture a drop of water falling on a hill, miles from the nearest stream. When the rain falls, some of the water soaks into the soil and some evaporates into the air, while the rest runs off the land. That water joins small streams and wetlands that drain into lakes and rivers, and eventually flows to the ocean. This is how trash, chemicals, or bacteria miles from a body of water can still end up in our rivers and lakes, and it’s why we all need to understand how our actions impact local waterways and those downstream! The urbanized area around Lansing lies within a portion of the Upper Grand River Watershed which can be broken into three smaller watershed areas: the Grand River Watershed (direct drainage), the Looking Glass River Watershed, and the Red Cedar River Watershed. The runoff from this area eventually drains into Lake Michigan at the mouth of the Grand River in Grand Haven, MI. Because of this connection, our actions at home have a direct impact on the health of the Great Lakes! Help Protect Our Water by Following These Tips! 1. -

Water Pollution from Agriculture: a Global Review

LED BY Water pollution from agriculture: a global review Executive summary © FAO & IWMI, 2017 I7754EN/1/08.17 Water pollution from agriculture: a global review Executive summary by Javier Mateo-Sagasta (IWMI), Sara Marjani Zadeh (FAO) and Hugh Turral with contributions from Jacob Burke (formerly FAO) Published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, 2017 and the International Water Management Institute on behalf of the Water Land and Ecosystems research program Colombo, 2017 FAO and IWMI encourage the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO and IWMI as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s and IWMI’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licence- request or addressed to [email protected]. FAO information products are available on the FAO website (www.fao.org/ publications) and can be purchased through [email protected]” © FAO and IWMI, 2017 Cover photograph: © Jim Holmes/IWMI Neil Palmer (IWMI) A GLOBAL WATER-QUALITY CRISIS AND THE ROLE OF AGRICULTURE Water pollution is a global challenge that has increased in both developed and developing countries, undermining economic growth as well as the physical and environmental health of billions of people. -

Sample Maintenance Provisions for Infiltration Basin

Sample Maintenance Provisions for Infiltration Basin System Description: Infiltration basins are designed to reduce runoff volumes from a site after development by intercepting the runoff and allowing it to slowly seep (infiltrate) into the underlying soil and groundwater. Most are designed to infiltrate the first 1/2” to 1” of runoff in an attempt to meet average annual predevelopment runoff volumes. The drainage areas served by an infiltration basin is usually 2-50 acres. Infiltration basins can also be designed to reduce peak flows by temporarily detaining runoff from larger storms and releasing it through outlet pipes or other controlled discharge devices. Pretreatment of the runoff is often provided to reduce sedimentation in the basin and prevent the risk of groundwater pollution, depending on the land use of the drainage area served by the basin. For this example, it is assumed that the infiltration basin is seeded with native warm season (prairie) grasses, has a pretreatment forebay, a stone trench in its center, one monitoring well located nearby, and has peak flow control incorporated into the design. Minimum Maintenance Requirements: To ensure the proper function of storm water infiltration basin, the following list of maintenance activities are recommended: 1. A minimum of 70% soil cover made up of native grasses must be maintained on the basin bottom to ensure infiltration rates. Periodic burning or mowing is recommended to enhance establishment of the prairie grasses (which may take 2-3 years) and maintain the minimum native cover. To reduce competition from cool season grasses (bluegrass, fescues, quack, etc.) and other weeds: o For the first year, cut to a 6” height three times – once each in June, July and early August. -

Chapter 6 - Infiltration Bmps

Chapter 6 - Infiltration BMPs Infiltration measures control stormwater quantity and quality by retaining runoff on-site and discharging it into the ground through absorption, straining, microbial decomposition and trapping of particulate matter. Infiltration systems should not be used if the intercepted runoff is anticipated to contain pollutants that can affect groundwater quality, such as hydrocarbons, nitrate, and chloride. When the subsoils are appropriate, an infiltration basin can be suitable for treating and controlling the runoff from very small to very large drainage areas. However, some commercial or industrial sites may have contaminants that may not be treatable by soil filtration and should be avoided. Figure 6-1 shows a typical infiltration basin. IMPORTANT: This chapter describes three common Infiltration BMPs: infiltration basins, dry wells, and infiltration trenches. In addition to these infiltration techniques, there are several Low Impact Design (LID) techniques that rely on infiltration in small systems dispersed throughout a site, rather than an end- of-pipe technique such as the infiltration basin. Sizing: Infiltration systems must be designed to retain a runoff volume equal to 1.0 inch times the subcatchment's impervious area plus 0.4 inch times the subcatchment's landscaped developed area and infiltrate this volume into the ground. The infiltration system must drain completely within 24 to 48 hours following the runoff event. Complete drainage is necessary to maintain aerobic conditions in the underlying soil to favor bacteria that aid in pollutant attenuation and to allow the system to recover its storage capacity before the next storm event. Site Suitability: The following are some recommendations on the suitability of a site: Soil Permeability: The permeability of the soil at the depth of the base of the proposed infiltration system should be no less than 0.50 inches per hour and no greater than 2.41 inches per hour. -

Hydrology Training Series

Hydrology Training Series Module 103 - Runoff Concepts Study Guide Module Description Objectives Upon completion of this module, the participant will be able to: 1. List and define the three types of runoff. 2. List and explain the principal climatic factors that affect runoff. 3. Describe the major watershed factors that affect runoff. The participant should be able to perform at ASK Level 3 (Perform with Supervision) after completing this module. Prerequisites Modules 101- Introduction to Hydrology and 102 - Precipitation References National Engineering Handbook, Section 4, Hydrology Engineering Field Manual Technical Release 55-Urban Hydrology for Small Watersheds Who May Take the Module This module is intended for all NRCS personnel who use hydrology in their work. Content This module discusses runoff data, flood runoff, annual runoff, and three major types of runoff. The important climatic and watershed factors that affect the conversion of storm rainfall to runoff are also presented. Introduction Runoff is that portion of the precipitation that makes its way toward stream channels, lakes, or oceans as surface flow. The intent of this module is to provide you with a basic understanding of the principal factors that affect runoff. Surface runoff is the primary cause of soil erosion and is, therefore, an important item in NRCS's goals of reducing soil erosion and improving water quality. Surface runoff also causes flooding. Flood runoff amounts and peak discharges are also required for the design of most conservation structural measures. Peak discharge will be discussed in Module 106. Runoff Data and Runoff Surface runoff is the principal cause of soil erosion. -

Quantitative Assessment of Surface Runoff and Base Flow Response to Multiple Factors in Pengchongjian Small Watershed

Article Quantitative Assessment of Surface Runoff and Base Flow Response to Multiple Factors in Pengchongjian Small Watershed Lei Ouyang 1,2 , Shiyu Liu 1,2,*, Jingping Ye 1,2, Zheng Liu 1,2, Fei Sheng 1,2, Rong Wang 1 and Zhihong Lu 1 1 School of Land Resources and Environment, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang 330045, China; [email protected] (L.O.); [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (F.S.); [email protected] (R.W.); [email protected] (Z.L.) 2 Key Laboratory of Poyang Lake Watershed Agricultural Resources and Ecology of Jiangxi Province, Nanchang 330045, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-158-7061-1238 Received: 22 July 2018; Accepted: 6 September 2018; Published: 10 September 2018 Abstract: Quantifying the impacts of multiple factors on surface runoff and base flow is essential for understanding the mechanism of hydrological response and local water resources management as well as preventing floods and droughts. Despite previous studies on quantitative impacts of multiple factors on runoff, there is still a need for assessment of the influence of these factors on both surface runoff and base flow in different temporal scales at the watershed level. The main objective of this paper was to quantify the influence of precipitation variation, evapotranspiration (ET) and vegetation restoration on surface runoff and base flow using empirical statistics and slope change ratio of cumulative quantities (SCRCQ) methods in Pengchongjian small watershed (116◦25048”–116◦2707” E, 29◦31044”–29◦32056” N, 2.9 km2), China. The results indicated that, the contribution rates of precipitation variation, ET and vegetation restoration to surface runoff were 42.1%, 28.5%, 29.4% in spring; 45.0%, 37.1%, 17.9% in summer; 30.1%, 29.4%, 40.5% in autumn; 16.7%, 35.1%, 48.2% in winter; and 35.0%, 38.7%, 26.3% in annual scale, respectively.