From Cleaner Production to Carbon Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report, and They Severally and Jointly Accept Legal Responsibility for the Truthfulness, Accuracy and Completeness of Its Contents

(A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People's Republic of China with limited liability) Stock Code: 1618 * For identification purpose only IMPORTANT NOTICE I. The Board and the Supervisory Committee of the Company and its Directors, Supervisors and senior management warrant that there are no false representations, misleading statements contained in or material omissions from the information set out in this annual report, and they severally and jointly accept legal responsibility for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of its contents. II. The Company convened the 14th meeting of the third session of the Board on 31 March 2020. All Directors of the Company attended the meeting. III. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu CPA LLP issued an unqualified audit report to the Company. IV. Guo Wenqing, the Chairman and legal representative of the Company, Zou Hongying, the Vice President and the Chief Accountant of the Company, and Fan Wanzhu, the Deputy Chief Accountant and the Head of the Financial Planning Department, have declared that they warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the financial report contained in this annual report. V. The proposal for profit distribution or transfer of capital reserve to share capital for the Reporting Period was considered by the Board The net profit attributable to Shareholders of the Company in the audited consolidated statement of MCC in 2019 amounted to RMB6,599,712 thousand and the undistributed profit of MCC headquarters amounted to RMB1,920,906 thousand. Based on the total share capital of 20,723.62 million shares, the Company proposed to distribute to all Shareholders a cash dividend of RMB0.72 (tax inclusive) for every 10 shares and the total cash dividend is RMB1,492,101 thousand, the remaining undistributed profit of RMB428,805 thousand will be used for the operation and development of the Company and rolled over to the coming year for distribution. -

Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results

14 August 2020 Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results Hang Seng Indexes Company Limited (“Hang Seng Indexes”) today announced the results of its review of the Hang Seng Family of Indexes for the quarter ended 30 June 2020. All changes will take effect on 7 September 2020 (Monday). 1. Hang Seng Index The following constituent changes will be made to the Hang Seng Index. The total number of constituents remains unchanged at 50. Inclusion: Code Company 1810 Xiaomi Corporation - W 2269 WuXi Biologics (Cayman) Inc. 9988 Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. - SW Removal: Code Company 83 Sino Land Co. Ltd. 151 Want Want China Holdings Ltd. 1088 China Shenhua Energy Co. Ltd. - H Shares The list of constituents is provided in Appendix 1. The Hang Seng Index Advisory Committee today reviewed the fast expanding innovation and new economy sectors in the Hong Kong capital market and agreed with the proposal from Hang Seng Indexes to conduct a comprehensive study on the composition of the Hang Seng Index. This holistic review will encompass various aspects including, but not limited to, composition and selection of constituents, number of constituents, weightings, and industry and geographical representation, etc. The underlying aim of the study is to ensure the Hang Seng Index continues to serve as the most representative and important benchmark of the Hong Kong stock market. Hang Seng Indexes will report its findings and propose recommendations to the Advisory Committee within six months. The number of constituents of the Hang Seng Index may increase during this period. Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results /2 2. -

Hang Seng China 50 Index Fund

September 2020 "Hang Seng Investment Series" HANG SENG CHINA 50 INDEX FUND IMPORTANT RISK WARNINGS / FUND INFORMATION FOR HONG KONG INVESTORS ● Hang Seng China 50 Index Fund (the "Fund") invests primarily in the constituent stocks of the Hang Seng China 50 Index (the "Index"). The coverage of the Index includes mainland China-listed A- shares and B-shares, Hong Kong-listed H-shares, red chip shares and shares of other Hong Kong-listed Mainland companies. ● The Net Asset Value of the Fund may be affected unfavourably by fluctuations in the exchange rates between the currencies of the Fund’s underlying investments and the Fund’s base currency and by changes in exchange rate controls. ● The Fund’s investment in equity securities is subject to general market risks, whose value may fluctuate. ● The Fund is subject to passive investment risk and tracking error risk. There can be no assurance of exact or identical replication at any time of the performance of the Index. ● The Fund is subject to concentration risk. The value of the Fund may be more volatile than that of a fund having a more diverse portfolio of investments, and may be more susceptible to adverse economic, political, policy, foreign exchange, liquidity, tax, legal or regulatory event affecting mainland China. ● Investing in an emerging market (such as mainland China) may involve increased risks and special considerations not typically associated with investment in more developed markets. The Fund is subject to the risk associated with high volatility and regulatory/exchanges requirements/policies of the equity market in an emerging market. -

Hang Seng China 50 Index View

For Managing the Hang Seng China 50 Index Sep 2019 | Version 1.2 Amendment History Date Description 1.0 May 2016 First Issue 1.1 November 2018 Updated Universe and share classes included in Section 3 – Constituent Eligibility 1.2 September 2019 Updated description of universe in Section 3 – Constituent Eligibility 1 Table of Contents Page 1. Overview 3 2. Management Responsibility 4 3. Constituent Eligibility 5 4. Index Review and Constituent Changes 7 5. Index Calculation 9 6. Index Rebalancing 10 7. Dissemination 11 8. Contact Information 12 9. Disclaimer 13 2 1 Overview 1.1 The Hang Seng China 50 Index (“HSC50”) measures the overall performance of the 50 largest China companies (in terms of market capitalisation) listed on the Hong Kong and / or mainland China stock markets. 1.2 The HSC50 is freefloat-adjusted, market-capitalisation weighted with a 10% cap on individual companies. 1.3 The HSC50 is calculated and disseminated real-time at 2-second intervals during the trading hours when the Hong Kong and/or Mainland stock markets are open. 3 2 Management Responsibility Hang Seng Indexes Company Ltd (“HSIL”) 2.1 HSIL is responsible for conducting regular reviews in accordance with the Index Methodology. 2.2 HSIL is responsible for monitoring company announcements and making ad hoc proposals – which must be approved by the Chairman of the HSI Advisory Committee – if constituent changes between the regular reviews are needed. 2.3 HSIL is responsible for seeking the HSI Advisory Committee’s endorsement of any special action in cases where, due to exceptional circumstances, an index review is not conducted according to the Index Methodology. -

恒生精选基金系列 Hang Seng Investment Series

恒生精选基金系列 HANG SENG INVESTMENT SERIES 年度财务报告 ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT 2014 目录 Contents 2 年度财务报告 2014 Annual Financial Report 2014 3 业绩表 Performance Table 10 受托人报告 Trustee's Report 11 独立审计师报告 Independent Auditor's Report 12 投资组合 Investment Portfolio 42 投资组合变动表 Statement of Movements in Portfolio Holdings 45 资产负债表 Statement of Assets and Liabilities 50 全面收益表 Statement of Comprehensive Income 55 权益变动表/ 基金份额持有人的资产净值变动表 Statement of Changes in Equity/ Statement of Changes in Net Assets Attributable to Unitholders 60 现金流量表 Cash Flow Statement 65 收益分配表 Distribution Statement 68 财务报表附注 Notes on the Financial Statements 114 指数基金与标的指数的业绩表现 Performance of Index Funds and Underlying Indexes 115 指数成份股披露 Index Constituent Stock Disclosure 116 基金管理与行政管理 Management and Administration 年度财务报告2014 Annual Financial Report 2014 基金中的基金系列 指数基金系列 中国大陆/香港基金系列 债券基金系列 Fund of Fund Series Index Fund Series Mainland China/Hong Kong Fund Series Bond Fund Series 恒生环球平稳增长基金 恒生指数基金 * 恒生指数基金 * 恒生环球债券基金 * Hang Seng Global Conservative Fund Hang Seng Index Fund * Hang Seng Index Fund * Hang Seng Global Bond Fund * 恒生环球均衡增长基金 恒生中型股指数基金 * 恒生中型股指数基金 * 恒生环球高收益债券基金 * Hang Seng Global Balanced Fund Hang Seng MidCap Index Fund * Hang Seng MidCap Index Fund * Hang Seng Global High Yield Bond Fund * 恒生环球高增长基金 恒生中国指数基金 * 恒生中国指数基金 * 恒生香港债券基金 * Hang Seng Global High Growth Fund Hang Seng China Index Fund * Hang Seng China Index Fund * Hang Seng Hong Kong Bond Fund * 恒生环球债券基金 * 恒生中国H股指数基金 * 恒生中国H股指数基金 * 恒生中国内地债券基金 * Hang Seng Global Bond Fund * Hang Seng China H-Share Index Fund * Hang -

Li & Fung Limited and Trinity Limited Selected As Constituent Stocks of The

Li & Fung Limited and Trinity Limited selected as constituent stocks of the Hang Seng Corporate Sustainability Index Series Li & Fung Limited (SEHK: 00494) has been selected as a constituent stock of the Hang Seng Corporate Sustainability Index and the Hang Seng Sustainability Benchmark Index; and Trinity Limited (SEHK: 00891) has been selected as a constituent stock of the Hang Seng Sustainability Benchmark Index. The Hang Seng Corporate Sustainability Index Series, launched in 2010 and updated on a yearly basis, measures the price performance of sizable and liquid Hong Kong and mainland China listed companies that perform well in the area of corporate sustainability. The Index Series aim to raise awareness about corporate sustainability (which encompasses environmental, social and corporate governance performance) and serve increasing international interest in sustainability investment. The constituent selection process includes consideration of the results from a corporate Sustainability Rating Assessment undertaken by RepuTex, an independent analytics and advisory firm, using its proprietary Sustainability Rating framework. The constituents of this investable index series are selected by ranking listed companies on the relevant stock markets to identify the top 150 in terms of market value. Turnover screening is applied and the index constituents are identified from this screened pool by selecting the highest-rated companies in the sustainability assessment. Please refer to the attachments* for details about the Hang Seng Corporate Sustainability Index Series and the constituent lists. * Source: Hang Seng Indexes PRESS RELEASE 10 August 2012 HANG SENG INDEXES ANNOUNCES INDEX REVIEW RESULTS Hang Seng Indexes Company Limited today announced the results of its review of the Hang Seng Family of Indexes for the quarter ended 30 June 2012. -

Findings of the Investigation Into China's Acts, Policies

OFFICE of the UNITED STATES TRADE REPRESENTATIVE EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT FINDINGS OF THE INVESTIGATION INTO CHINA’S ACTS, POLICIES, AND PRACTICES RELATED TO TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY, AND INNOVATION UNDER SECTION 301 OF THE TRADE ACT OF 1974 March 22, 2018 Abbreviations and Acronyms Acronym Definition 3PLA People’s Liberation Army, Third Department 4WD four-wheel drive AAFA American Apparel & Footwear Association ABA American Bar Association ABC Agriculture Bank of China ABPIA American Bridal & Prom Industry Association ACC American Chemistry Council AEI American Enterprise Institute AGIC Asia-Germany Industrial Promotion Capital AI artificial intelligence AmCham American Chamber of Commerce Shanghai AML Anti-Monopoly Law AMSC American Superconductor Corporation APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation APT advanced persistent threat AQSIQ Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine ATI Allegheny Technologies, Inc AVIC Aviation Industry Corporation of China AVICEM ACIF Electromechanical Systems Co., Ltd AWD all-wheel drive BCM Bank of Communications BEA U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis BGI Shenzhen Beijing Genomics Institute BIO Biotechnology Innovation Organization BIS Bureau of Industry and Security BoC Bank of China BRI Belt and Road Initiative BRIC Brazil, Russia, India, and China C&C command-and-control CAAC Civil Aviation Administration of China CAIGA China Aviation Industry General Aircraft Co. CAST China Association of Science and Technology CCBC China Construction Bank Corporation -

Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results

Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results (Hong Kong, 26 February 2021) – Hang Seng Indexes Company Limited ('Hang Seng Indexes Company') today announced the results of its review of the Hang Seng Family of Indexes for the quarter ended 31 December 2020. All changes will take effect on 15 March 2021 (Monday). 1. Hang Seng Index The following constituent changes will be made to the Hang Seng Index. The total number of constituents will increase from 52 to 55. Inclusion: Code Company 241 Alibaba Health Information Technology Ltd. 960 Longfor Group Holdings Ltd. 6862 Haidilao International Holding Ltd. The list of constituents is provided in Appendix 1. 2. Hang Seng China Enterprises Index The following constituent changes will be made to the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index. The total number of constituents will be reset to 50 from current 52. Inclusion: Code Company 6098 Country Garden Services Holdings Co. Ltd. 9633 Nongfu Spring Co., Ltd. - H Shares Removal: Code Company 586 China Conch Venture Holdings Ltd. 857 PetroChina Co. Ltd. - H Shares 1044 Hengan International Group Co. Ltd. 1193 China Resources Gas Group Ltd. The list of constituents is provided in Appendix 2. Changes in constituent companies of the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index will also be applied to the Hang Seng China Enterprises Smart Index. |PUBLIC| Hang Seng Indexes Announces Index Review Results /2 3. Hang Seng TECH Index The following constituent changes will be made to the Hang Seng TECH Index. The total number of constituents will be reset to 30 from current 32. Inclusion: Code Company 6690 Haier Smart Home Co., Ltd. -

Annual Report

( A joint stock limited liability company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China ) Together we make it better Annual Report Annual 2 / Company Profile 3 / Definitions 7 / Important Notice 8 / Corporate Information 10 / Financial Highlights 15 / Honors and Awards 18 / Message from the Chairman 22 / Message from the President 27 / Discussion and Analysis 90 / Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 101 / Corporate Governance Contents 122 / Report of the Board of Directors 137 / Report of the Board of Supervisors 141 / Connected Transactions and the Implementation of the Management System for Connected Transactions 148 / Significant Events 150 / Organizational Structure 152 / Independent Auditor’s Report 308 / Appendix I : Unaudited Supplementary Financial Information 312 / Appendix II : Liquidity Coverage Ratio 313 / Appendix III : Leverage Ratio 315 / Appendix IV : Composition of Capital 330 / Appendix V : Reference Materials for Shareholders Postal Savings Bank of China Co., Ltd. Company Profile Postal Savings Bank of China is a leading large retail commercial bank in China, strategically focuses on providing financial services to communities, SMEs and “Sannong” customers and is committed to meeting the financial needs of the most promising customers during China’s economic transformation. Meanwhile, the Bank actively serves large corporate customers and participates in the construction of major projects, making important contributions to China’s economic development. With approximately 40,000 outlets and services covering over 553 million individual customers, Postal Savings Bank of China has shown its superior asset quality and significant development potential. At present, we have established an all-around e-banking system consisting of online banking, mobile banking, self-service banking, telephone banking, and WeChat banking etc., forming a financial service landscape in which electronic banking connects with physical network and offline physical banking keeps pace with online virtual banking. -

2020 Annual Report (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability) WHAT IS COUNTRY GARDEN?

Country Garden Holdings Company Limited Stock Code: 2007 碧桂園控股有限公 司 2020 ANNUAL REP O R T 2020 Annual Report (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) WHAT IS COUNTRY GARDEN? Country Garden is a diversified technology company that creates a happy life for the world. We are committed to robotics Technology is advancing from day to day. In fact, the age of robots is already here. Country Garden is committed to scientific innovation. Our team is growing by the day, particularly our team of top scientists. Today, we have over 200 thousand employees, including more than 1,000 PhDs. Their combined brainpower channels the power of science to craft better lives for all, and to make China a more technologically advanced country. We established Bright Dream Robotics to develop smart construction systems built around construction robots, prefabrication systems, and BIM. Bright Dream Robotics is working to achieve the perfect marriage of safety, quality, speed, and economy, and is leading a revolution in the construction sector. Meanwhile, Bright Dream Robotics is also developing, manufacturing, and operating robots for catering, healthcare, agriculture, and home services. We set up Qianxi Robotics to build the world’s most advanced robot restaurant. This is how we can offer our community food that is tasty, safe, nutritious, healthy, and reasonably priced and provide an entirely new dining experience to the consumers. We build good housing and good communities Country Garden is committed to supporting China’s new urbanization process. We bring true craft and care to the task of making homes that are safe, healthy, attractive, economical, practical, and long-lasting. -

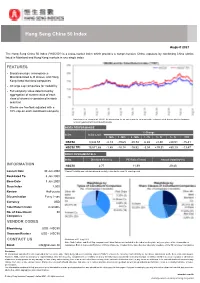

Hang Seng China 50 Index View

Hang Seng China 50 Index August 2021 The Hang Seng China 50 Index ("HSC50") is a cross-market index which provides a comprehensive China exposure by combining China stocks listed in Mainland and Hong Kong markets in one single index. FEATURES ■ Broad coverage encompasses Mainland-listed A, B shares, and Hong Kong listed Mainland companies ■ 50 large cap companies for tradability ■ Full company value determined by aggregation of market value of each class of shares is considered in stock selection ■ Stocks are freefloat-adjusted with a 10% cap on each constituent company Data has been rebased at 100.00. All information for an index prior to its launch date is back-tested, back-tested performance reflects hypothetical historical performance. INDEX PERFORMANCE % Change Index Index Level 1 - Mth 3 - Mth 6 - Mth 1 - Yr 3 - Yr 5 - Yr YTD HSC50 8,548.57 -2.13 -19.69 -20.74 -6.32 +8.90 +28.51 -15.41 HSC50 TRI 15,571.65 -1.85 -18.18 -18.92 -3.94 +19.31 +50.19 -13.47 INDEX FUNDAMENTALS Index Dividend Yield (%) PE Ratio (Times) Annual Volatility*(%) INFORMATION HSC50 2.77 11.99 20.40 Launch Date 30 Jun 2008 *Annual Volatility was calculated based on daily return for the past 12-month period. Backdated To 3 Jan 2000 Base Date 3 Jan 2000 Base Index 2,000 Review Half-yearly Dissemination Every 2 sec Currency USD Total Return Index Available No. of Constituent 50 Companies VENDOR CODES Bloomberg USD - HSC50 Thomson Reuters USD - .HSC50 CONTACT US All data as at 31 Aug 2021 Note: Both A-share and Red Chip companies of China Unicorn are included in the index but they take only one place of the 50 constituent Email [email protected] companies. -

2009 Annual Report, and in Note 62 to the Bank’S 2009 Financial Statements

CONTENTS Corporate Profile 1 Results in Brief 2 Five-year Financial Summary 3 Major Milestones 4 Recognition 5 Chairman's Statement 7 Chief Executive's Report 9 Corporate Responsibility 14 Corporate Governance and Other Information 17 Management Discussion and Analysis - Business in Hong Kong 30 - Business on the Mainland 36 - Financial Review 39 Biographical Details of Directors 55 Biographical Details of Senior Management 64 Report of the Directors 68 2009 Financial Statements 76 Independent Auditor's Report 228 Supplementary Notes to the Financial Statements (unaudited) 229 Analysis of Shareholders 252 Subsidiaries 253 Corporate Information and Calendar 254 CORPORATE PROFILE Established in 1933, Hang Seng Bank is the largest Hong Kong-incorporated bank and among the 50 largest listed banks in the world in terms of market capitalisation (HK$220.6 billion as at the end of December 2009). In Hong Kong, we serve over one-third of the population through more than 220 service outlets, including 104 branches. We also maintain a branch in Shenzhen for foreign currency wholesale business, branches in Macau and Singapore, and representative offices in Xiamen and Taipei. Established in 2007, wholly owned mainland China subsidiary Hang Seng Bank (China) Limited operates a network of 37 outlets in Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Dongguan, Fuzhou, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Tianjin, Kunming and Foshan. Hang Seng is a principal member of the HSBC Group, one of the world’s largest banking and financial services organisations. 1 RESULTS IN