Reflections on Sigurd P. Ramfjord

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Placa Dentobacteriana Sobre La Patologia. Estudio De Caso, En

Odontología de Biblioteca Facultad U.M.S.N.H. Odontología de Biblioteca Facultad U.M.S.N.H. Odontología de Biblioteca Facultad U.M.S.N.H. UNIVERSIDAD MICHOACANA DE SAN NICOLAS DE HIDALGO FACULTAD DE ODONTOLOGIA Odontología de TESIS Biblioteca PLACA DENTOBACTERIANA Facultad U.M.S.N.H.SOBRE LA PATOLOGIA PARODONTAL. ESTUDIO DE CASO: EN CENTRO DE SALUD DE QUIROGA, MICHOACAN. PRESENTA:Odontología KARLA ALEJANDRAde GONZALEZ CERVANTES Biblioteca FacultadPARA OBTENER EL TITULO DE: 1-· U.M.S.N.H.CIRUJANO DENTISTA .. ASESOR DRA. LAURA ALEJANDRA HERRERA CATALAN COASESOR Odontología DRA. GUILLERMINA RAMIREZ NAVARROde Biblioteca MORELIAFacultad MICH , OCTUBRE. 2005 U.M.S.N.H. 1- CONTENIDO IV DEDICATORIAS __________________ V JUSTIFICACIÓN 1 Odontología~------------------------ INTRODUCCIÓNde 2 ~-------------------,..----- Biblioteca1.ANTECEDENTES _________________ 5 Facultad 1.1 Generales---------------------------- 5 U.M.S.N.H. 1.2. Placa bacteriana _________________________12 1.2.1. Cutícula relacionada al huésped 13 1.2.2. Introducción general a la formación de placaOdontología bacteriana 15 1.2.3. Clasificación y composición de la placa bacteriana 20 1.2.4. Metabolismo y fisiología en la placade bacteriana 25 1.2.5. Depósitos sobre las superficies dentarias 29 1.2.6. Factores queBiblioteca predisponen al desarrollo de placa bacteriana 36 1.2.6.1. Locales Facultad 38 1.2.6.2. Sistémicos 51 1.2.7. Microbiología de la enfermedadU.M.S.N.H. parodontal 59 1.2.7.1. Mecanismos de adherencia 63 1.2.8 Control de placa bacteriana 70 1.2.9. Prácticas higiénicas a través de la historia Odontología73 de 2 OBJETIVO GENERAL _______________ 97 2.1 Objetivos específicos _______________________Biblioteca 97 Facultad 3. -

Gingival Overgrowth: an Enigma to Periodontists

Galore International Journal of Health Sciences and Research Vol.2; Issue: 1; March 2017 Website: www.gijhsr.com Review Article P-ISSN: 2456-9321 Gingival Overgrowth: An Enigma to Periodontists Dr. Rosiline James Post Graduate Student, Rural Dental College, Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, Loni, India ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT sex predilection, and effect of local inflammation also affected the severity of Gingival overgrowth which is an abnormal the overgrowth. growth of the periodontal tissue is mainly The capacity of the host to deal associated with dental plaque-related metabolically with chronically administered inflammation and drug therapy. Its true drugs, the responsiveness of gingival tissue incidence in the general population is unknown. Gingival enlargement produces aesthetic to the drugs, and the pre existing gingival changes, pain, gingival bleeding and periodontal condition may differ among different disorders. The three classes of drugs namely, individuals. Moreover, calcium channel anti epileptic, immune-suppressive, produce blockers are mainly prescribed for post- important changes in fibroblast function, which middle-aged patients to control induce an increase in the extracellular matrix of hypertension, cardiac insufficiencies or the gingival connective tissue. In the majority of myocardial events, whereas phenytoin and those patients for whom dosage reduction, or cyclosporine A (CsA) are prescribed for a drug discontinuation or substitution is not wide range of patients due to their wide possible, and for whom prophylactic measures spectrum of efficacy. These make it difficult have failed, surgical excision of gingival tissue to evaluate the etiology of drug induced remains the only treatment of choice. Brunet et al. [1] gingival overgrowth caused by phenytoin, CsA, and calcium channel blockers and to [2] Key words: Gingival enlargement, gingival compare the factors involved. -

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General De Investigación Y Posgrado

UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE BAJA CALIFORNIA Dirección General de Investigación y Posgrado PROPUESTA DE UN ESTUDIO DE FACTIBILIDAD PARA LA CREACION DE ESPECIALIDADES ODONTOLOGICAS EN LA FACULTAD DE ODONTOLOGIA MEXICAL DE LA UABC. ANALISIS DE LA NECESIDAD SOCIAL La creación de un programa de posgrado en la Facultad de Odontología Mexicali, en la U.A.B.C., que contemple las diferentes áreas odontológicas a nivel de especialidad, está acorde a las necesidades de nuestra sociedad en su entorno estatal y nacional, ya que la demanda de servicios especializados aumenta día a día en forma considerable, siendo actualmente insuficientes los especialistas existentes, egresados de otras facultades del país para atender dichas demandas. La búsqueda de un perfil acorde a nuestras necesidades propone, la formación de especialistas con actitud diferente a la tradicional, que como sabemos están concentrados más en la resolución de problemas específicos de salud, que -

Dental Medicine

MAGAZINE OF THE TUFTS UNIVERSITY DENTAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION FALL 2011 VOL. 15 NO. 2 Dental meDicine Practicing dentistry behind bars PLUS: A CONVERSATION WITH DEAN THOMAS n RE-THINKING PAIN MEDS 28889c01.indd 1 11/11/11 6:05 PM restorative work Peter Arsenault, D94, an associate clinical professor of prosthodontics and operative dentistry, counts woodworking and furniture refinishing among his skills. This past summer, he volunteered to restore the conference table in the Becker Board Room on the seventh floor of One Kneeland Street. The board room, Arsenault notes, was dedicated the same year that he and his wife, Karin Andrenyi Arsenault, graduated from the dental school. The project, he adds, wasn’t all that different from what he does for a living: “It’s kind of like buffing out a composite restoration,” he says. “It’s like working on a big tooth.” PHOTO: ALONSO NICHOLS 28889c02.indd 1 11/11/11 6:07 PM contents FALL 2011 VOLUME 15 NO. 2 features 12 Pivotal Profession A conversation with Huw F. Thomas, the dental school’s 16th dean. By Helene Ragovin COVER STORY 16 Dentistry Behind Bars Practicing in a prison is a mix of the peculiar and the familiar, say alumni whose career paths have taken them inside the corrections system. By Helene Ragovin 22 Chew On This In tending to pets’ oral health needs, veterinarians take their cues from human dentistry. By Genevieve Rajewski 26 Life After Death His life was the only thing the Nazis did not 12 take from him, so John Saunders, D52, was determined to make it a life well-lived. -

Redalyc.Historia De La Periodoncia: Primeros Rasgos De Definición De Un

Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Sistema de Información Científica Carlos Afanador Ruiz, Camilo Duque Naranjo, Constanza Gómez de Ramírez Historia de la periodoncia: primeros rasgos de definición de un espacio social y conceptual y proceso de institucionalización en Colombia. parte I. una imagen de la periodoncia... Revista Colombiana de Filosofía de la Ciencia, vol. 3, núm. 11, 2004, pp. 77-103, Universidad El Bosque Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=41401104 Revista Colombiana de Filosofía de la Ciencia, ISSN (Versión impresa): 0124-4620 [email protected] Universidad El Bosque Colombia ¿Cómo citar? Fascículo completo Más información del artículo Página de la revista www.redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Revista Colombiana de Filosofía de la Ciencia Vol. III. Nos. 10 y 11. Págs. 77-103 HISTORIA DE LA PERIODONCIA: Primeros rasgos de definición de un espacio social y conceptual y proceso de institucionalización en Colombia. Parte I. Una imagen de la periodoncia a través de su historia y de su historiografía* Carlos Afanador Ruiz**, Camilo Duque Naranjo***, Constanza Gómez de Ramírez**** RESUMEN La periodoncia es la especialidad de la odontología que comprende la prevención, el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y pronóstico de las enfermedades de los tejidos que rodean y soportan al diente y sus sustitutos, y el mantenimiento en salud, función y estética en esas estructuras y tejidos. En Colombia es una especialidad relativamente joven pero con una trayectoria y expresión institucional importante. Hasta el presente no se ha realizado un trabajo sistemático que dé cuenta de los procesos por los cuales llegó a definirse como un espacio diferenciado y reconocido en el país. -

10 Danksagung

AusderUniversitätsklinikfürZahn-,Mund-undKieferheilkunde derAlbert-Ludwigs-UniversitätFreiburgimBreisgau AbteilungPoliklinikfürZahnerhaltungskundeundParodontologie (ÄrztlicherDirektor:Prof.Dr.E.Hellwig) FührtdieVerwendungeinesInterdentalstimulators zusätzlichzuZahnbürste,ZahnpastaundZahnseide zueinerVerringerungvorhandenerPlaque? −SystematischeLiteraturübersichtundkontrollierteklinischeStudie − INAUGURAL-DISSERTATION zur ErlangungdesZahnmedizinischenDoktorgrades derMedizinischenFakultät derAlbert-Ludwigs-Universität FreiburgimBreisgau vorgelegt2004 vonImkeNinaSybilleBecker geboreninBühl/Baden Dekan: Prof.Dr.J.Zentner 1. Gutachter: Prof.Dr.G.Krekeler 2. Gutachter: Prof.Dr.Dr.J.Düker JahrderPromotion:2004 I Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung .............................................................................................................. 1 2 Literaturübersicht................................................................................................ 3 2.1 Einführung.............................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Plaque..................................................................................................................... 4 2.2.1 EpidemiologiedesPlaquebefalls ........................................................................... 4 2.2.2 ÄtiologiederdentalenPlaque ................................................................................ 5 2.3 Gingivopathien ...................................................................................................... -

Effect of Curcumin on De Novo Plaque Formation ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Maradi AP et al.: Effect of Curcumin on de novo Plaque Formation ORIGINAL RESEARCH Effect of Curcumin on de novo Plaque Formation: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial Arun P Maradi1, KKN Saranya2, Ritika Chhalani3, Jayashree Sajjanar4, Arunkumar B. Sajjanar5, Fazal Ilahi Jamesha6 1 - Reader, Dept of periodontics , Sri Ramakrishna Dental College Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. 2,3,6-PG Students, Dept of Periodontics, Sri Ramakrishna Dental College Correspondence to: Coimbatore, Tamilnadu. 4-Senior lecturer, Dept of prosthodontics, Swargiya Dr. Arun P Maradi, Reader, Dept of periodontics, Sri Dadasaheb Kalmegh Smruti Dental College and Hospital, Wanadongri, Nagpur.5- Ramakrishna dental college Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu. Reader, Dept Of Pedodontics & Preventive Dentistry, Swargiya Dadasaheb Contact Us: www.ijohmr.com Kalmegh Smruti Dental College And Hospital Wanadongri, Nagpur. ABSTRACT Background: The major drawback of the products for chemical plaque control is the numerous side effects associated with their use. Turmeric, a rhizome of Curcuma longa, is a herb which has proven properties like anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, hepatoprotective, immunostimulant, antiseptic, and antimutagenic. De novo plaque regrowth study is a typical first screening method for the evaluation of a new mouthrinse formulation. Hence in this study, the effect of curcumin on de novo plaque formation is evaluated and compared with chlorhexidine as positive control and water as negative control. Methods: 42 dental students volunteered for this double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial. Professional tooth cleaning was done in the preparatory phase, so that plaque score of 0 was obtained. After scaling, the students abstained from all mechanical measures of plaque control for 2 days but rinsed with mouth rinse alone [Water with flavoring agent/ Curcumin mouth rinse (0.1%)/ Chlorhexidine mouthrinse (Rexidin 0.2%)]. -

Espodontologia.Pdf

PROPUESTA DE UN ESTUDIO DE FACTIBILIDAD PARA LA CREACION DE ESPECIALIDADES ODONTOLOGICAS EN LA FACULTAD DE ODONTOLOGIA MEXICAL DE LA UABC. ANALISIS DE LA NECESIDAD SOCIAL La creación de un programa de posgrado en la Facultad de Odontología Mexicali, en la U.A.B.C., que contemple las diferentes áreas odontológicas a nivel de especialidad, está acorde a las necesidades de nuestra sociedad en su entorno estatal y nacional, ya que la demanda de servicios especializados aumenta día a día en forma considerable, siendo actualmente insuficientes los especialistas existentes, egresados de otras facultades del país para atender dichas demandas. La búsqueda de un perfil acorde a nuestras necesidades propone, la formación de especialistas con actitud diferente a la tradicional, que como sabemos están concentrados más en la resolución de problemas específicos de salud, que en el origen de sus causas, por lo que debemos encaminar esfuerzos en la formación de especialistas que los lleven en pos de nuevas alternativas de tratamiento. La población de Baja California, requiere de un posgrado formal y continuo que sea consolidado a mediano plazo con los productos que de él emanen, como son: egresados de calidad, líneas de investigación clínica, tesistas, equipos de investigación, equipos multidisciplinarios de atención a la comunidad, programas de actualización, intercambios nacionales e internacional, vinculación con los diferentes sectores de la población y lo más importante, programas que fomenten y coadyuven la formación de la población. OBJETIVOS Objetivo General.- Estructurar un programa de posgrado que responda a las necesidades de formación de especialistas de alto nivel académico y permita: en el campo de investigación clínica, crear nuevos conceptos en el quehacer odontológico en base al nuevo conocimiento. -

Clinical Practice in Restorative Dentistry | University of Warwick

09/28/21 MD974: Clinical Practice in Restorative Dentistry | University of Warwick MD974: Clinical Practice in Restorative View Online Dentistry (2016/17) Abduo, Jaafar. 2013. ‘Occlusal Schemes for Complete Dentures: A Systematic Review.’ The International Journal of Prosthodontics 26(1):26–33. doi: 10.11607/ijp.3168. Adams, D., J. S. Brudvik, and M. F. Chan. 1998. ‘The Swing-Lock Removable Partial Denture in Clinical Practice.’ Dental Update 25(2):80–84. Allen, P. F., D. J. Witter, and N. H. Wilson. 1995. ‘The Role of the Shortened Dental Arch Concept in the Management of Reduced Dentitions.’ British Dental Journal 179(9):355–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808921. Anon. 1983. ‘Influence of the Vertical Dimension in the Treatment of Myofascial Pain-Dysfunction Syndrome.’ The Journal Of Prosthetic Dentistry 50(5):700–709. Anon. n.d. ‘Orthodontics: The Orthodontic-Restorative Interface: 1. Patient Assessment.’ DentalUpdate 37(2):74–80. Anon. n.d. ‘Splint Adjustment Guide.’ Anon. n.d. ‘Splint Appliance Selection Guide.’ Auerbach, Stephen M., Daniel M. Laskin, Lisa Maria E. Frantsve, and Tamara Orr. 2001. ‘Depression, Pain, Exposure to Stressful Life Events, and Long-Term Outcomes in Temporomandibular Disorder Patients.’ Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 59(6):628–33. doi: 10.1053/joms.2001.23371. Avila, G. 2009. ‘A Novel Decision-Making Process for Tooth Retention or Extraction.’ Journal of Periodontology 80(3). Azarbal M. 1977. ‘Comparison of Myo-Monitor Centric Position to Centric Relation and Centric Occlusion.’ The Journal Of Prosthetic Dentistry [J Prosthet Dent] 1977 Sep; Vol 38(3). Badersten, Anita, Rolf Nilveus, and Jan Egelberg. -

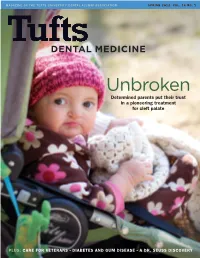

Spring 2012 Vol

MAGAZINE OF THE TUFTS UNIVERSITY DENTAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION SPRING 2012 VOL. 16 NO. 1 NONPROFIT ORG. School of Dental Medicine U.S. POSTAGE 136 Harrison Avenue PAID BOSTON, MA Boston, ma 02111 PERMIT NO. 1161 SPORTS FOR SCHOLARSHIP www.tufts.edu/dental OPeN Dental meDicine Come join the Tufts University Dental Alumni Association for the 30th Annual Wide Open Golf & Tennis Tournament Unbroken Determined parents put their trust Monday, September 24, 2012 in a pioneering treatment Wellesley Country Club for cleft palate 300 Wellesley Ave. Wellesley, Massachusetts Tufts Dental alumni, faculty, family and friends are invited to participate! revival All proceeds benefit the For centuries, the history of Dental Alumni Student Loan Fund the Wampanoag Indians went unrecorded, and unrecognized. Chester Soliz, D61, set out to Schedule of Events change that. For more on his story, turn to page 10. Golf and Tennis Registration 9:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Golf Tournament 11 a.m. shotgun start Lunch included Tennis tournament 2 to 4 p.m. Reception 4 p.m. Awards Dinner 5 p.m. Registration Fees TUFTS UNIVERSITY OFFICE OF PUBLICATION Golf Tournament $350/player $1,300/foursome if signed up together Tennis Tournament $200/player Reception and Dinner Only $75 for guests and noncompetitors S 8331 05/12 n n PHOTO: BRAD DECECCO PLUS: CARE FOR VETERANS DIABETES AND GUM DISEASE A DR. SEUSS DISCOVERY 30035cvr.indd 1 4/26/12 2:55 PM 2012 Wide Open Tournament Registration Form Name_________________________________________________ SPORTS FOR SCHOLARSHIP Graduation year or affiliation with Tufts Dental___________ Guest(s) name(s)______________________________________ Address_______________________________________________ ______________________________________________________ WiDe OPeN Daytime phone________________________________________ Email_________________________________________________ My handicap is___________. -

United States Patent Office Patented Feb

3,639,571 United States Patent Office Patented Feb. 1, 1972 2 3,639,571. One of the problems encountered in inhibiting bac COMPOSITION AND METHOD FOR RETARDING terial deposits is the provision of an anti-bacterial agent PLAQUE AND DENTAL CALCULUS that will be effective in a neutral or mildly acidic en Samuel Turesky, 84 Wallis Road, Chestnut Hill, Mass. Vironment. Thus, for example, the compositions disclosed 02167, and Irving Glickman, 24 Manor House Road, by Buonocore et al., in U.S. Pat. 2,955,984 and incorpo NoNewton, Drawing. Mass. Continuation-in-part 02159 of application Ser. No. rating compounds of the formula 530,781, Mar. 1, 1966, which is a continuation-in-part OR3 of application Ser. No. 679,994, Nov. 2, 1967, which in turn is a continuation-in-part of application Ser. No. R-0--0 763,491, Sept. 23, 1968. This application Jan. 29, 1970, 10 Ó R, Ser. No. 6,933 (wherein an R1,R2 and Rs are variously alkyls, aralkyls, Int, C. A61k 7/16 hythrogens, ammonium or alkali metal) are not fully U.S. C. 424-54 13 Claims Satisfactory because they tend to have the greatest effect at lower pH levels than those experienced in the mouth, ABSTRACT OF THE DISCLOSURE 15 and other less acidic environments, over any long period of time. Formation of bacteria, e.g. of the type resulting in for Another problem encountered in inhibiting bacterial mation of bacteria, e.g. of the type resulting in the for deposits is the provision of an anti-bacterial agent that mation of dental plaque and dental calculus, is retarded will remain effective in environments wherein the agent by exposing surfaces to be protected to a composition 20 may be subjected to attack by enzymes. -

Centuries in Periodontology Dr

Periodontics Centuries In Periodontology Dr. Chandulal D. Dhalkari, Associate Professor and Guide, Government Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad. Dr. Pallav Ganatra, Postgraduate Student, Government Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad. Dr. Pawan Sawalakhe, Postgraduate Student, Government Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad. Department Of Periodontology Government Dental College and Hospital, Aurangabad , Maharashtra.-431001 Introduction etiology of periodontal disease". He believed 2. Ya kon or disease of the soft investing he Speciality of Periodontics has a long that inflammation of the gingiva could be tissues of the body. history in civilization, dating back to caused by accumulations of pituita or 3. Chong ya or dental caries Tprehistoric, early middle eastern and calculus, with gingival haemorrhage occuring One gingival condition. "Ya-Heou" in Egyptian cultures where there is skeletal and in cases of persistant diseases.1,2 which the gums were described as red, written evidence of periodontal diseases. Romans soft, swollen and a fetid purulent matter Ancient Indian and Chinese histories describe The Romans had a high regard for oral exudes from them, the teeth are not scurvy and other conditions and advocate hygiene. They used "dentifricium" - bones, painful. In another condition was 'Tcharg- cleansing of teeth for health. On through the egg shells and oyster shells having been burnt Che-Tong" "Flow of purulent mucous Greek and Roman civilizations, through the and sometimes mixed with honey, Among the mixed with blood. Bad smelling breath. renaissance and into modern times, disease of Roman, Auius Cornelius Celsus (25 BC - 50 Tooth falls". The treatment was by the periodontium as well as remedies and AD) referred to disease that affects the soft draughts, mouth washes.