2021.0114 Masters Final Submission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Program of the 75Th Anniversary Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 75 TH ANNIVERSARY MEETING April 14−April 18, 2010 St. Louis, Missouri THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 75th Anniversary Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2010 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 75th Anniversary Meeting 3 Contents 4............... Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5……….….2010 Award Recipients 10.................Maps of the America’s Center 12 ................Maps of Renaissance Grand St. Louis 14 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 15 .............. General Information 18. ............. Featured Sessions 20 .............. Summary Schedule 25 .............. A Word about the Sessions 27............... Program 161................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 167............... Presidents of SAA . 168............... Annual Meeting Sites 169............... Exhibit Map 170................Exhibitor Directory 180................SAA Committees and Task Forces 184………….Index of participants 4 Program of the 75th Anniversary Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting America’s Center APRIL 16, 2010 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2009 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

Song of the Year

General Field Page 1 of 15 Category 3 - Song Of The Year 015. AMAZING 031. AYO TECHNOLOGY Category 3 Seal, songwriter (Seal) N. Hills, Curtis Jackson, Timothy Song Of The Year 016. AMBITIONS Mosley & Justin Timberlake, A Songwriter(s) Award. A song is eligible if it was Rudy Roopchan, songwriter songwriters (50 Cent Featuring Justin first released or if it first achieved prominence (Sunchasers) Timberlake & Timbaland) during the Eligibility Year. (Artist names appear in parentheses.) Singles or Tracks only. 017. AMERICAN ANTHEM 032. BABY Angie Stone & Charles Tatum, 001. THE ACTRESS Gene Scheer, songwriter (Norah Jones) songwriters; Curtis Mayfield & K. Tiffany Petrossi, songwriter (Tiffany 018. AMNESIA Norton, songwriters (Angie Stone Petrossi) Brian Lapin, Mozella & Shelly Peiken, Featuring Betty Wright) 002. AFTER HOURS songwriters (Mozella) Dennis Bell, Julia Garrison, Kim 019. AND THE RAIN 033. BACK IN JUNE José Promis, songwriter (José Promis) Outerbridge & Victor Sanchez, Buck Aaron Thomas & Gary Wayne songwriters (Infinite Embrace Zaiontz, songwriters (Jokers Wild 034. BACK IN YOUR HEAD Featuring Casey Benjamin) Band) Sara Quin & Tegan Quin, songwriters (Tegan And Sara) 003. AFTER YOU 020. ANDUHYAUN Dick Wagner, songwriter (Wensday) Jimmy Lee Young, songwriter (Jimmy 035. BARTENDER Akon Thiam & T-Pain, songwriters 004. AGAIN & AGAIN Lee Young) (T-Pain Featuring Akon) Inara George & Greg Kurstin, 021. ANGEL songwriters (The Bird And The Bee) Chris Cartier, songwriter (Chris 036. BE GOOD OR BE GONE Fionn Regan, songwriter (Fionn 005. AIN'T NO TIME Cartier) Regan) Grace Potter, songwriter (Grace Potter 022. ANGEL & The Nocturnals) Chaka Khan & James Q. Wright, 037. BE GOOD TO ME Kara DioGuardi, Niclas Molinder & 006. -

Het Verhaal Van De 340 Songs Inhoud

Philippe Margotin en Jean-Michel Guesdon Rollingthe Stones compleet HET VERHAAL VAN DE 340 SONGS INHOUD 6 _ Voorwoord 8 _ De geboorte van een band 13 _ Ian Stewart, de zesde Stone 14 _ Come On / I Want To Be Loved 18 _ Andrew Loog Oldham, uitvinder van The Rolling Stones 20 _ I Wanna Be Your Man / Stoned EP DATUM UITGEBRACHT ALBUM Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down The Road Apiece ALBUM DATUM UITGEBRACHT 10 januari 1964 EP Everybody Needs Somebody To Love Under The Boardwalk DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : (er zijn ook andere data, zoals DATUM UITGEBRACHT Verenigd Koninkrijk : 17 april 1964 16, 17 of 18 januari genoemd Verenigd Koninkrijk : Down Home Girl I Can’t Be Satisfi ed 15 januari 1965 Label Decca als datum van uitbrengen) 14 augustus 1964 You Can’t Catch Me Pain In My Heart Label Decca REF : LK 4605 Label Decca Label Decca Time Is On My Side Off The Hook REF : LK 4661 12 weken op nummer 1 REF : DFE 8560 REF : DFE 8590 10 weken op nummer 1 What A Shame Susie Q Grown Up Wrong TH TH TH ROING (Get Your Kicks On) Route 66 FIVE I Just Want To Make Love To You Honest I Do ROING ROING I Need You Baby (Mona) Now I’ve Got A Witness (Like Uncle Phil And Uncle Gene) Little By Little H ROLLIN TONS NOW VRNIGD TATEN EBRUARI 965) I’m A King Bee Everybody Needs Somebody To Love / Down Home Girl / You Can’t Catch Me / Heart Of Stone / What A Shame / I Need You Baby (Mona) / Down The Road Carol Apiece / Off The Hook / Pain In My Heart / Oh Baby (We Got A Good Thing SONS Tell Me (You’re Coming Back) If You Need Me Goin’) / Little Red Rooster / Surprise, Surprise. -

Aftershocks Rock Nepal As Quake Toll Tops 2,500

SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, APRIL 27, 2015 RAJJAB 8, 1436 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Turkey seeks Violence mars Sweets, soup Kipchoge to boost trade Baltimore vanish as Pak adds London cooperation protest over aims for halal Marathon title with Kuwait custody death export14 boost to18 collection 2Aftershocks9 rock Nepal Min 21º Max 36º as quake toll tops 2,500 High Tide 07:20 & 17:45 Amir expresses sorrow over casualties Low Tide 00:10 & 12:35 40 PAGES NO: 16503 150 FILS KATHMANDU/KUWAIT: Powerful aftershocks rocked Nafisi acquitted, Nepal yesterday, panicking survivors of a quake that killed more than 2,500 and triggering new avalanches at Everest base camp, as mass cremations were held in Saudi embassy the devastated capital Kathmandu. Terrified residents, many forced to camp out in the capital after Saturday’s sues MP Dashti 7.8-magnitude quake reduced buildings to rubble, were jolted by a 6.7-magnitude aftershock that compounded By B Izzak the worst disaster to hit the impoverished Himalayan nation in more than 80 years. KUWAIT: In a series of court decisions, the court of At overstretched hospitals, where medics were also cassation yesterday upheld the acquittal of Islamist treating patients in hastily erected tents, staff were academic and activist Abdullah Al-Nafisi from forced to flee buildings for fear of further collapses. charges of insulting Shiites. Nafisi, a former MP, was “Electricity has been cut off, communication systems charged with insulting Shiites under the national uni- are congested and hospitals are crowded and are run- ty law, which stipulates several years of imprison- ning out of room for storing dead bodies,” Oxfam ment for those convicted. -

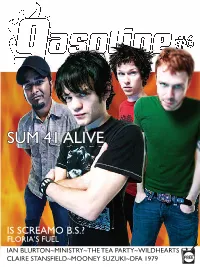

Sum 41 Alive

SSUMUM 4411 AALIVELIVE IS SCREAMO B.S.? FLORIA’S FUEL IAN BLURTON~MINISTRY~THE TEA PARTY~WILDHEARTS CLAIRE STANSFIELD~MOONEY SUZUKI~DFA 1979 THE JERRY CAN The summer is the season of rock. Tours roll across the coun- try like mobile homes in a Florida hurricane. The most memo- rable for this magazine/bar owner were the Warped Tour and Wakestock, where such bands as Bad Religion, Billy Talent, Alexisonfire, Closet Monster, The Trews and Crowned King had audiences in mosh-pit frenzies. At Wakestock, in Wasaga Beach, Ont., Gasoline, Fox Racing, and Bluenotes rocked so hard at their two-day private cottage party that local authorities shut down the stage after Magneta Lane and Flashlight Brown. Poor Moneen didn't get to crush the eardrums of the drunken revellers. That was day one! Day two was an even bigger party with the live music again shut down. The Reason, Moneen and Crowned King owned the patio until Alexisonfire and their crew rolled into party. Gasoline would also like to thank Chuck (see cover story) and other UN officials for making sure that the boys in Sum41 made it back to the Bovine for another cocktail, despite the nearby mortar and gunfire during their Warchild excursion. Nice job. Darryl Fine Editor-in-Chief CONTENTS 6 Lowdown News 8 Ian Blurton and C’mon – by Keith Carman 10 Sum41 – by Karen Bliss 14 Floria Sigismondi – by Nick Krewen 16 Alexisonfire and “screamo” – by Karen Bliss 18 Smash it up – photos by Paula Wilson 20 Whiskey and Rock – by Seth Fenn 22 Claire Stansfield – by Karen Bliss 24 Tea Party – by Mitch Joel -

Elenco Volumi Esposti Su Musica

COMUNE DI ALPIGNANO ASSESSORATO ALLA CULTURA In Biblioteca ... CD musica straniera pop-rock 1 Abba The album CD 782.42 ABB Bryan Adams So far so good CD 782.42 ADA Aerosmith Big Ones CD 782.42 AER Aerosmith Rockin' the joint CD 782.42 AER Christina Stripped CD 782.42 AGU Aguilera Air Moon safari CD 782.42 AIR The Alan I Robot CD 782.42 ALA Parsons Project America The definitive pop collection CD 782.42 AME Anastacia Anastacia CD 782.42 ANA Anastacia Pieces of a dream CD 782.42 ANA The Ark State of The Ark CD 782.42 ARK Richard Ashcroft Alone With Everybody CD 782.42 ASH Audioslave Out of exile CD 782.42 AUD Aventura God's project CD 782.42 AVE Backstreet Boys Millennium CD 782.42 BAC Backstreet Boys Backstreet's Back CD 782.42 BAC Joan Baez The Best of Joan C. Baez CD 782.42 BAE Basement Jaxx Kish kash CD 782.42 BAS B.B. King & Eric Riding With the King CD 782.42 BBK Clapton Beastie Boys Licensed to ill CD 782.42 BEA The Beatles The Beatles CD 782.42 BEA The Beatles The Beatles CD 782.42 BEA Beck Mutations CD 782.42 BEC George Benson The best of George Benson CD 782.42 BEN Samuele Bersani Che vita! CD 782.42 BER The B-52'S The B-52'S CD 782.42 BFI Björk SelmaSongs CD 782.42 BJO Björk Debut CD 782.42 BJO The Black Eyed Elephunk CD 782.42 BLA Peas The Black Eyed Monkey business CD 782.42 BLA Peas Blink-182 Blink-182 CD 782.42 BLI 2 Blur 13 CD 782.42 BLU Blues Brothers & Live from Chicago's house of blues CD 782.42 BLU Friends Blue Guilty CD 782.42 BLU Blue Best of Blue CD 782.42 BLU James Blunt Chasing time: the Bedlam sessions CD 782.42 BLU Michael Bolton Greatest Hits 1985-1995 CD 782.42 BOL Jon Bon Jovi Crush CD 782.42 BON David Bowie Live Santa Moica '72 CD 782.42 BOW Goran Bregovic Ederlezi CD 782.42 BRE James Brown Sex machine: The very best of James Brown CD 782.42 BRO Jackson Browne The Next Voice you Hear CD 782.42 BRO Michael Bublé It's time CD 782.42 BUB Jeff Buckley Sketches for my Sweetheart the Drunk CD 782.42 BUC AA. -

Killing Joke Love Like Blood Mp3, Flac, Wma

Killing Joke Love Like Blood mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Love Like Blood Country: UK Released: 1985 Style: Post-Punk MP3 version RAR size: 1688 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1104 mb WMA version RAR size: 1708 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 251 Other Formats: VOX VOC AHX MPC VQF ADX AAC Tracklist A Love Like Blood 4:14 B Blue Feather (Version) 4:09 Companies, etc. Marketed By – Polydor Phonographic Copyright (p) – E.G. Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – E.G. Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – E.G. Music Ltd. Pressed By – PRS Baarn Published By – E.G. Music Ltd. Lacquer Cut At – PRS Baarn Credits Photography By – Jeff Veitch Producer – Chris Kimsey Sleeve – Killing Joke, Rob O'Connor Written-By – Killing Joke Notes Label variation with E'G at bottom of labels. ℗ 1985 E.G. Records Ltd. © 1985 E.G. Records Ltd. © 1985 E.G. Music Ltd. (on labels) Marketed by Polydor Made in Holland Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout Side A): 881 618 7 1W1 ℗ 1985 670 06 Matrix / Runout (Runout Side B): 881 618 7 2W1 ℗ 1985 670 06 Matrix / Runout (Label Side A): 881 618-7 1W Matrix / Runout (Label Side B): 881 618-7 2W Rights Society: B.I.E.M. STEMRA Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year EGO 20, 881 Love Like Blood (7", EGO 20, 881 Killing Joke EG, EG UK 1985 618-7 Single, Blu) 618-7 Love Like Blood (7", 881 618-7 Killing Joke EG 881 618-7 Australasia 1985 Single) Love Like Blood (12", 881 618-1 Killing Joke EG 881 618-1 Portugal 1985 Maxi) Love Like Blood (12", 881 618-1 Killing Joke EG 881 618-1 France 1985 Maxi) Love Like Blood (7", 7DM 0133 Killing Joke Polydor 7DM 0133 Japan 1985 Single) Related Music albums to Love Like Blood by Killing Joke Shriekback / Killing Joke - In Concert-360 Killing Joke - MMXII Killing Joke - Kings And Queens Killing Joke - The Great Gathering Killing Joke - Revelations Killing Joke - ...No Way Out But Forward Go Killing Joke - Almost Red Killing Joke - Killing Joke Killing Joke - Fire Dances Killing Joke - America Killing Joke - Night Time Killing Joke - Absolute Dissent. -

Marillion.Htm

http://www.altatensione.it/marillion.htm MARILLION Abbiamo incontrato a Milano una band in salute, che ha fatto la storia del prog, ma che ora cerca di allontanarsi dal solito "clichè", per approdare ad altri lidi...lontano dalle major e con l'aiuto del web e dei fans. Articolo e reportage di Lory Lorena, foto e filmato di John Lorena. La storia dei Marillion inizia nel 1978, un anno durante il quale la scena musicale internazionale vive una rivoluzione clamorosa, con la nascita di fenomeni effimeri tra i quali spicca il movimento punk. E' il periodo in cui tramonta più o meno definitivamente un particolare discorso musicale intrapreso da diversi anni e denominato "rock progressivo" o, in taluni casi, "rock romantico". Nonostante la confusione e il cambiamento che pervade il panorama internazionale, nasce in Inghilterra un gruppo chiamato Silmarillion, il fondatore di questo nucleo di "avventurieri nostalgici", è Mick Pointer, batterista proveniente da Bicks e attualmente leader del gruppo new-progressive Arena. L'intento iniziale è costituire una band strumentale. Dopo un inizio stentato, Pointer e il bassista Doug Irvine devono già ricominciare a cercare nuovi musicisti, in quanto il chitarrista e il tastierista precedenti decidono di andarsene quasi immediatamente. Ai tanti annunci pubblicati sui comuni giornali musicali risulta particolarmente interessato un certo Steven Thomas Rothery, chitarrista originario dello Yorkshire, nato il 25 novembre 1959 e proveniente da esperienze con i Dark Horse e i Purple Haze. L'arrivo di Rothery, insieme all'ingaggio di tale Brian Jelliman alle tastiere, apporta nuova linfa vitale alla rischiosa attività intrapresa e i quattro decidono di continuare. -

![ADAM NEELY [INTERMEDIATE] WHO? Adam Neely Is One of the Biggest Names on Music Theory Youtube Right Now](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3197/adam-neely-intermediate-who-adam-neely-is-one-of-the-biggest-names-on-music-theory-youtube-right-now-2793197.webp)

ADAM NEELY [INTERMEDIATE] WHO? Adam Neely Is One of the Biggest Names on Music Theory Youtube Right Now

FSU APC FREE SOFTWARE & SOUNDS/STUDENT DISCOUNTS/TUTORIAL MASTER LIST TUTORIALS AND THINGS FOR LEARNIN’S MICHAEL WHITE’S FUNDAMENTALS OF MIXING [BEGINNER – ADVANCED] WHAT’S ALL THIS ‘BOUT, THEN? Michael White’s Fundamentals of Mixing is a 62 part, almost 32-hour YouTube course on every part of mixing and mastering. The dude’s a professional mixer with 30 years of experience working with big names like Whitney Houston and 3 Doors Down (among others) and it shows. This is BY FAR the best tutorial series for mixing/mastering on YouTube. It covers everything from how to place your monitors to compression to re-amping guitars to panning to multitrack tape saturation. Primarily, he focuses on the practical application of effects and certain techniques and less on the technical aspects or the “what’s this knob do” part of mixing. Everything he discusses is applicable to every genre and DAW. Besides the Fundamentals of Mixing course, I’ve grabbed a few supplementary videos from his tips videos and linked them right below. If you’re wanting something specific that’s not listed here, I’d look through his channel (especially the 133 video tips playlist). You might find what you’re looking for. You can also watch his series on his website, which has a couple of bonus videos at the end of the series focused on mastering (it requires registration but is free). OTHER RECOMMENDED VIDEOS TO WATCH FROM HIS CHANNEL: Prioritizing Levels in a Mix – Around the Levels and Panning section (Lesson 15). Creating Dynamic Contrast in a Mix – Around the Filters and Subtractive EQ section (Lesson 16). -

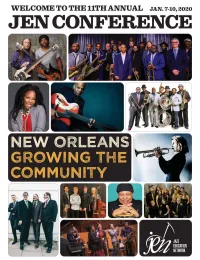

The 2020 Jazz Education Network Conference

THE 2020 JAZZ EDUCATION NETWORK CONFERENCE JEN FEATURES ADONIS ROSE’S NEW ORLEANS! When Adonis Rose took over as artis- tic director of the New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, the group was on the verge of collapse. Through sweat, hard work and lots of faith, the drum- mer/bandleader has the 18-piece group cooking again. Witness them at the JEN Scholarship Concert on Friday night! 38 MEET THE 98 CHECKING IN ARTISTS! WITH ROXY COSS Meet the Artists is a new fea- The wicked good tenor player ture at this year’s JEN con- is also a staunch advocate for ference. During dedicat- equity in jazz. She discusses ed exhibit hours this week, how she founded the Women attendees have an opportu- In Jazz Organization, serves nity to say hello to dozens of on JEN’s Women In Jazz stars from jazz and jazz edu- Committee and strives to help cation. Just head down to create more opportunities for Elite Hall (Level 1)! women on the bandstand! WELCOME TO JEN! JEN CONFERENCE SCHEDULE 10 JEN President’s Welcome 36 Meet the Artists 12 Mayor of New Orleans’ Welcome 38 Hyatt Regency New Orleans Map 14 Meet the Sponsors 40 Tuesday, Jan. 7, Jazz Industry/Music 16 The JEN Board of Directors Business Symposium Schedule 18 JEN Initiatives 42 Tuesday, Jan. 7, JEN Conference Schedule 44 Wednesday, Jan. 8, JEN Conference Schedule 60 Thursday Jan. 9, JEN Conference Schedule Friday, Jan. 10, JEN HONOREES 78 JEN Conference Schedule 22 Scholarship Recipients 24 Composer Showcase Honorees VISIT OUR JEN EXHIBITORS! 26 Sisters In Jazz Honorees 92 Exhibitor List 28 JEN Commissioned Charts 93 Exhibition Hall Map 30 JEN Distinguished Award Honorees 94 JEN Guide Advertiser Index On the cover, clockwise from top left: Bass Extremes with Steve Bailey and Victor Wooten, The New Orleans Jazz Orchestra, the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, Bria Skonberg, Western Michigan University’s Gold Company, Chucho Valdés, the ChiArts Jazz Combo, Carmen Bradford and RJAM, Brubecks Play Brubeck, Tia Fuller and Mark Whitfield. -

Aglobal Response Events, Recordings Aim to Raise Chesney's Millions for Tsunami Victims

$6.99 (U.S.), $8.99 (CAN.), £5.50 (U.K.), 8.95 (EUROPE), Y2,500 (JAPAN) aw a zW jjBXNCTCC 3 -DIGIT 908 - _ IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIlII111I1lIIIlII11I11III I IIIIIII JtBL2408043$i APR06 A04 B0103 MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE H A LONG BEACH CA 90807 -3402 1111 NMI lift/ 15, 2005 www.billboard.com THE INTERNATIONAL AUTHORITY ON MUSIC, VIr ''GITAL ENTERTAINMENT ÌIOTH YEAR JANUARY HOT SPOTS Kenny AGlobal Response Events, Recordings Aim To Raise Chesney's Millions For Tsunami Victims A Billboard and Billboard Radio Monitor staff report. 10 Artie Shaw: ATribute As the world continues to respond to the devas- Billboard remembe-s the tation in Southeast Asia following the Dec. 26 late bandleader and clarinetist Choice earthquake and tsunami, the global music com- in a personal tribute by munity is corning together in an unprecedented Tamara Conniff. Country outpouring of support for relief efforts. (Continued on page 60) Star Gets Personal At Caribbean Retreat BY DEBORAH EVANS PRICE 13 He's Game NASHVILLE -After more than a Dr. Dre"s latest protégé, the Game, decade of hit records and relent- creates buzz with his upcoming less touring, Kenny Chesney LINKIN PARK: GRATITUDE, RESPONSIBILITY AND OBLIGATION Aftermath /G -U nit/Interscope ascended to the top of the coun- album debut, "Th2 Documentary." try format last November when he claimed the entertainer of the year prize at the Country Music Assn. Awards. Now he's exercis- Latin Biz Awaits ing his hard -won creative clout to take something of a mLsical left turn. Download Boom On Jan. 25, BNA Records will release "Be As You Are: Songs BY LEILA COBO From an Old Blue Chair," a Latin music fans who visit legal music download album that singerisongwriter stores may experience a sense of déjà vu.