Arxiv:2104.06232V1 [Quant-Ph] 13 Apr 2021 Implementing Such Ideas in the Laboratory Is Made Pos- Not Detect the Probed State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Quantum Physics

Further Quantum Physics Concepts in quantum physics and the structure of hydrogen and helium atoms Prof Andrew Steane January 18, 2005 2 Contents 1 Introduction 7 1.1 Quantum physics and atoms . 7 1.1.1 The role of classical and quantum mechanics . 9 1.2 Atomic physics—some preliminaries . .... 9 1.2.1 Textbooks...................................... 10 2 The 1-dimensional projectile: an example for revision 11 2.1 Classicaltreatment................................. ..... 11 2.2 Quantum treatment . 13 2.2.1 Mainfeatures..................................... 13 2.2.2 Precise quantum analysis . 13 3 Hydrogen 17 3.1 Some semi-classical estimates . 17 3.2 2-body system: reduced mass . 18 3.2.1 Reduced mass in quantum 2-body problem . 19 3.3 Solution of Schr¨odinger equation for hydrogen . ..... 20 3.3.1 General features of the radial solution . 21 3.3.2 Precisesolution.................................. 21 3.3.3 Meanradius...................................... 25 3.3.4 How to remember hydrogen . 25 3.3.5 Mainpoints.................................... 25 3.3.6 Appendix on series solution of hydrogen equation, off syllabus . 26 3 4 CONTENTS 4 Hydrogen-like systems and spectra 27 4.1 Hydrogen-like systems . 27 4.2 Spectroscopy ........................................ 29 4.2.1 Main points for use of grating spectrograph . ...... 29 4.2.2 Resolution...................................... 30 4.2.3 Usefulness of both emission and absorption methods . 30 4.3 The spectrum for hydrogen . 31 5 Introduction to fine structure and spin 33 5.1 Experimental observation of fine structure . ..... 33 5.2 TheDiracresult ..................................... 34 5.3 Schr¨odinger method to account for fine structure . 35 5.4 Physical nature of orbital and spin angular momenta . -

Quantum Mechanics C (Physics 130C) Winter 2015 Assignment 2

University of California at San Diego { Department of Physics { Prof. John McGreevy Quantum Mechanics C (Physics 130C) Winter 2015 Assignment 2 Posted January 14, 2015 Due 11am Thursday, January 22, 2015 Please remember to put your name at the top of your homework. Go look at the Physics 130C web site; there might be something new and interesting there. Reading: Preskill's Quantum Information Notes, Chapter 2.1, 2.2. 1. More linear algebra exercises. (a) Show that an operator with matrix representation 1 1 1 P = 2 1 1 is a projector. (b) Show that a projector with no kernel is the identity operator. 2. Complete sets of commuting operators. In the orthonormal basis fjnign=1;2;3, the Hermitian operators A^ and B^ are represented by the matrices A and B: 0a 0 0 1 0 0 ib 01 A = @0 a 0 A ;B = @−ib 0 0A ; 0 0 −a 0 0 b with a; b real. (a) Determine the eigenvalues of B^. Indicate whether its spectrum is degenerate or not. (b) Check that A and B commute. Use this to show that A^ and B^ do so also. (c) Find an orthonormal basis of eigenvectors common to A and B (and thus to A^ and B^) and specify the eigenvalues for each eigenvector. (d) Which of the following six sets form a complete set of commuting operators for this Hilbert space? (Recall that a complete set of commuting operators allow us to specify an orthonormal basis by their eigenvalues.) fA^g; fB^g; fA;^ B^g; fA^2; B^g; fA;^ B^2g; fA^2; B^2g: 1 3.A positive operator is one whose eigenvalues are all positive. -

![On the Symmetry of the Quantum-Mechanical Particle in a Cubic Box Arxiv:1310.5136 [Quant-Ph] [9] Hern´Andez-Castillo a O and Lemus R 2013 J](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3436/on-the-symmetry-of-the-quantum-mechanical-particle-in-a-cubic-box-arxiv-1310-5136-quant-ph-9-hern%C2%B4andez-castillo-a-o-and-lemus-r-2013-j-563436.webp)

On the Symmetry of the Quantum-Mechanical Particle in a Cubic Box Arxiv:1310.5136 [Quant-Ph] [9] Hern´Andez-Castillo a O and Lemus R 2013 J

On the symmetry of the quantum-mechanical particle in a cubic box Francisco M. Fern´andez INIFTA (UNLP, CCT La Plata-CONICET), Blvd. 113 y 64 S/N, Sucursal 4, Casilla de Correo 16, 1900 La Plata, Argentina E-mail: [email protected] arXiv:1310.5136v2 [quant-ph] 25 Dec 2014 Particle in a cubic box 2 Abstract. In this paper we show that the point-group (geometrical) symmetry is insufficient to account for the degeneracy of the energy levels of the particle in a cubic box. The discrepancy is due to hidden (dynamical symmetry). We obtain the operators that commute with the Hamiltonian one and connect eigenfunctions of different symmetries. We also show that the addition of a suitable potential inside the box breaks the dynamical symmetry but preserves the geometrical one.The resulting degeneracy is that predicted by point-group symmetry. 1. Introduction The particle in a one-dimensional box with impenetrable walls is one of the first models discussed in most introductory books on quantum mechanics and quantum chemistry [1, 2]. It is suitable for showing how energy quantization appears as a result of certain boundary conditions. Once we have the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions for this model one can proceed to two-dimensional boxes and discuss the conditions that render the Schr¨odinger equation separable [1]. The particular case of a square box is suitable for discussing the concept of degeneracy [1]. The next step is the discussion of a particle in a three-dimensional box and in particular the cubic box as a representative of a quantum-mechanical model with high symmetry [2]. -

Molecular Energy Levels

MOLECULAR ENERGY LEVELS DR IMRANA ASHRAF OUTLINE q MOLECULE q MOLECULAR ORBITAL THEORY q MOLECULAR TRANSITIONS q INTERACTION OF RADIATION WITH MATTER q TYPES OF MOLECULAR ENERGY LEVELS q MOLECULE q In nature there exist 92 different elements that correspond to stable atoms. q These atoms can form larger entities- called molecules. q The number of atoms in a molecule vary from two - as in N2 - to many thousand as in DNA, protiens etc. q Molecules form when the total energy of the electrons is lower in the molecule than in individual atoms. q The reason comes from the Aufbau principle - to put electrons into the lowest energy configuration in atoms. q The same principle goes for molecules. q MOLECULE q Properties of molecules depend on: § The specific kind of atoms they are composed of. § The spatial structure of the molecules - the way in which the atoms are arranged within the molecule. § The binding energy of atoms or atomic groups in the molecule. TYPES OF MOLECULES q MONOATOMIC MOLECULES § The elements that do not have tendency to form molecules. § Elements which are stable single atom molecules are the noble gases : helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon and radon. q DIATOMIC MOLECULES § Diatomic molecules are composed of only two atoms - of the same or different elements. § Examples: hydrogen (H2), oxygen (O2), carbon monoxide (CO), nitric oxide (NO) q POLYATOMIC MOLECULES § Polyatomic molecules consist of a stable system comprising three or more atoms. TYPES OF MOLECULES q Empirical, Molecular And Structural Formulas q Empirical formula: Indicates the simplest whole number ratio of all the atoms in a molecule. -

Statistical Mechanics, Lecture Notes Part2

4. Two-level systems 4.1 Introduction Two-level systems, that is systems with essentially only two energy levels are important kind of systems, as at low enough temperatures, only the two lowest energy levels will be involved. Especially important are solids where each atom has two levels with different energies depending on whether the electron of the atom has spin up or down. We consider a set of N distinguishable ”atoms” each with two energy levels. The atoms in a solid are of course identical but we can distinguish them, as they are located in fixed places in the crystal lattice. The energy of these two levels are ε and ε . It is easy to write down the partition function for an atom 0 1 −ε0 / kB T −ε1 / kBT −ε 0 / k BT −ε / kB T Z = e + e = e (1+ e ) = Z0 ⋅ Zterm where ε is the energy difference between the two levels. We have written the partition sum as a product of a zero-point factor and a “thermal” factor. This is handy as in most physical connections we will have the logarithm of the partition sum and we will then get a sum of two terms: one giving the zero- point contribution, the other giving the thermal contribution. At thermal dynamical equilibrium we then have the occupation numbers in the two levels N −ε 0/kBT N n0 = e = Z 1+ e−ε /k BT −ε /k BT N −ε 1 /k BT Ne n1 = e = Z 1 + e−ε /k BT We see that at very low temperatures almost all the particles are in the ground state while at high temperatures there is essentially the same number of particles in the two levels. -

About Supersymmetric Hydrogen

About Supersymmetric Hydrogen Robin Schneider 12 supervised by Prof. Yuji Tachikawa2 Prof. Guido Festuccia1 August 31, 2017 1Theoretical Physics - Uppsala University 2Kavli IPMU - The University of Tokyo 1 Abstract The energy levels of atomic hydrogen obey an n2 degeneracy at O(α2). It is a consequence of an so(4) symmetry, which is broken by relativistic effects such as the fine or hyperfine structure, which have an explicit angular momentum and spin dependence at higher order in α. The energy spectra of hydrogenlike bound states with underlying supersym- metry show some interesting properties. For example, in a theory with N = 1, the hyperfine splitting disappears and the spectrum is described by supermul- tiplets with energies solely determined by the super spin j and main quantum number n [1, 2]. Adding more supercharges appears to simplify the spectrum even more. For a given excitation Vl, the spectrum is then described by a single multiplet for which the energy depends only on the angular momentum l and n. In 2015 Caron-Huot and Henn showed that hydrogenlike bound states in N = 4 super Yang Mills theory preserve the n2 degeneracy of hydrogen for relativistic corrections up to O(α3) [3]. Their investigations are based on the dual super conformal symmetry of N = 4 super Yang Mills. It is expected that this result also holds for higher orders in α. The goal of this thesis is to classify the different energy spectra of super- symmetric hydrogen, and then reproduce the results found in [3] by means of conventional quantum field theory. Unfortunately, it turns out that the tech- niques used for hydrogen in (S)QED are not suitable to determine the energy corrections in a model where the photon has a massless scalar superpartner. -

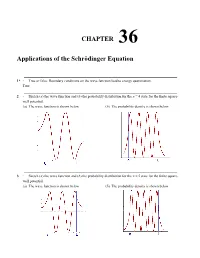

Chapter 36 Applications of the Schrödinger Equation

CHAPTER 36 Applications of the Schrödinger Equation 1* ∙ True or false: Boundary conditions on the wave function lead to energy quantization. True 2 ∙ Sketch (a) the wave function and (b) the probability distribution for the n = 4 state for the finite square- well potential. (a) The wave function is shown below (b) The probability density is shown below 3 ∙ Sketch (a) the wave function and (b) the probability distribution for the n = 5 state for the finite square- well potential. (a) The wave function is shown below (b) The probability density is shown below Chapter 36 Applications of the Schrödinger Equation 4 ∙∙ Show that the expectation value <x> = ∫ xΨ 2 dx is zero for both the ground and the first excited states of the harmonic oscillator. ∞ 2 The integral ∫ xψ dx = 0 because the integrand is an odd function of x for the ground state as well as any −∞ excited state of the harmonic oscillator. 5* ∙∙ Use the procedure of Example 36-1 to verify that the energy of the first excited state of the harmonic _ ω ω 3 _ 0. (Note: Rather than solve for a again, use the result a = m 0/2h obtained in Example oscillator is E1 = 2 h 36-1.) 2 dψ 2 2 ψ −ax −ax − 2 −ax The wave function is = A1 x e (see Equ. 36-25). Then = A1 e 2 ax A1 e and dx 2ψ d − −ax2 − −ax2 2 3 −ax2 2 3 − −ax2 = 2 axA1 e 4 axA1 e + 4 a x A1 e = (4 a x 6ax) A1 e . -

![Arxiv:2108.13143V1 [Cond-Mat.Quant-Gas]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4811/arxiv-2108-13143v1-cond-mat-quant-gas-3254811.webp)

Arxiv:2108.13143V1 [Cond-Mat.Quant-Gas]

Probing many-body systems near spectral degeneracies K. Ziegler Institut f¨ur Physik, Universit¨at Augsburg, D-86135 Augsburg, Germany (Dated: August 31, 2021) The diagonal elements of the time correlation matrix are used to probe closed quantum systems that are measured at random times. This enables us to extract two distinct parts of the quantum evolution, a recurrent part and an exponentially decaying part. This separation is strongly affected when spectral degeneracies occur, for instance, in the presence of spontaneous symmetry breaking. Moreover, the slowest decay rate is determined by the smallest energy level spacing, and this decay rate diverges at the spectral degeneracies. Probing the quantum evolution with the diagonal elements of the time correlation matrix is discussed as a general concept and tested in the case of a bosonic Josephson junction. It reveals for the latter characteristic properties at the transition to Hilbert- space localization. I. INTRODUCTION Symmetries play a central role in classical as well as in quantum many-body systems. They determine the macroscopic behavior of these systems. Moreover, symmetries of macroscopic states reflect symme- tries and spontaneous symmetry breaking of the underlying system. For instance, the groundstates of the Ising model with ferromagnetic nearest-neighbor spin-spin coupling are | ↑,..., ↑i and | ↓,..., ↓i. This two-fold degeneracy is a consequence of the symmetry of the Hamiltonian. Then we experience spontaneous symmetry breaking when we add an arbitrarily small perturbation (e.g., a small magnetic field or special boundary conditions) that breaks the symmetry. This leads to a lifting of the degeneracy of the two quantum states. -

Chapter 7. Symmetry Labeling of Molecular Energies Notes: • Most of the Material Presented in This Chapter Is Taken from Bunker and Jensen (1998), Chap

Chapter 7. Symmetry Labeling of Molecular Energies Notes: • Most of the material presented in this chapter is taken from Bunker and Jensen (1998), Chap. 6, and Bunker and Jensen (2005), Chap. 7. 7.1 Hamiltonian Symmetry Operations We have seen in section 6.1.4 of the previous chapter that any elements of the CNPI group, and therefore any elements of the MS group, associated with a given molecule commute with the corresponding molecular Hamiltonian. That is, given a symmetry operator R we have ! ˆ 0 # "H , R$ = 0. (7.1) We also saw that this implies that if a wave function ! of the Hamiltonian is transformed by R such that ! R = R! , then this transformed function is also a wave function of the Hamiltonian with the same energy level as the original function, since ˆ 0 R ˆ 0 ˆ 0 0 0 R H ! n = H R! n = RH ! n = REn! n = En! n , (7.2) 0 where En is the energy associated with the wave function ! n . For a non-degenerate energy level, this in turn implies that R ! n = c! n , (7.3) with c some constant. As we will now see, the determination of the different values that this constant can take is central to the use of symmetry labels, associated with each irreducible representation of the MS group, for identifying the energy levels of a molecule. 7.1.1 Non-degenerate Energy Levels Consider again the case of a MS group operator R acting on a wave function ! n of non- 0 degenerate energy level En . -

PHY 481/581 Intro Nano- MSE: Applying Simple Quantum Mechanics to Nanoscience Problems, Part I

PHY 481/581 Intro Nano- MSE: Applying simple Quantum Mechanics to nanoscience problems, part I http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/1 Time dependent Schrödinger Equation in 3D, Many problems concern stationary states, i.e. things do not change over time, then we can use the much simpler tine independent Schrödinger Equation in 3D, e.g. The potential is infinitely high, equivalently, the well is infinitely deep Since potential energy V is zero inside the box 2 Since the Schrödinger equation is linear Now we need to Since we normalize 3 know k This sets the scale for the wave function, we need to have it at the right scale to calculate expectation values, this condition means that the particle definitely exist (with certainty, probability 100 %) in some region of space, in our case in between x = 0 and L There are infinitely many energy levels, their spacing depends on the size of the box, there is on E0 = 0 as this is forbidden by the 4 uncertainty principle Again, the potential is infinitely high, equivalently, the 3D well is infinitely deep Generalization to three dimensions is straightforward, kind of everything is there three times because of the three dimensions, not particularly good approximation for a quantum dot (since the potential energy outside of the box is assumed to infinite, which does not happen in physics, also the real quantum dot may have some shape with some crystallite faces, while we are just assuming a rectangular box or cube Particle in a cube, there will be degenerate energy levels, i.e. -

Lecture 12 Atomic Structure Atomic Structure: Background

Lecture 12 Atomic structure Atomic structure: background Our studies of hydrogen-like atoms revealed that the spectrum of the Hamiltonian, pˆ2 1 Ze2 Hˆ0 = 2m − 4π"0 r is characterized by large n2-fold degeneracy. However, although the non-relativistic Schr¨odingerHamiltonian provides a useful platform, the formulation is a little too na¨ıve. The Hamiltonian is subject to several classes of “corrections”, which lead to important physical ramifications (which reach beyond the realm of atomic physics). In this lecture, we outline these effects, before moving on to discuss multi-electron atoms in the next. Atomic structure: hydrogen atom revisited As with any centrally symmetric potential, stationary solutions of Hˆ0 index by quantum numbers n#m, ψn!m(r)=Rn!(r)Y!m(θ,φ). For atomic hydrogen, n2-degenerate energy levels set by 2 1 e2 m e2 1 E = Ry , Ry = = n − n2 4π" 2 2 4π" 2a ! 0 " ! 0 0 2 4π#0 ! where m is reduced mass (ca. electron mass), and a0 = e2 m . For higher single-electron ions (He+, Li2+, etc.), E = Z 2 Ry . n − n2 Allowed combinations of quantum numbers: n # Subshell(s) 1 0 1s 20, 12s 2p 30, 1, 23s 3p 3d n 0 (n 1) ns ··· − ··· Atomic structure: hydrogen atom revisited However, treatment of hydrogen atom inherently non-relativistic: pˆ2 1 Ze2 Hˆ0 = 2m − 4π"0 r is only the leading term in relativistic treatment (Dirac theory). Such relativistic corrections begin to impact when the electron becomes relativistic, i.e. v c. ∼ Since, for Coulomb potential, 2 k.e. = p.e. -

Organic Electronic Devices Week 2: Electronic Structure Lecture 2.3: Application of the Schrödinger Equation

Organic Electronic Devices Week 2: Electronic Structure Lecture 2.3: Application of the Schrödinger Equation Bryan W. Boudouris Chemical Engineering Purdue University 1 Lecture Overview and Learning Objectives • Concepts to be Covered in this Lecture Segment • Implementation of the Time-independent Schrödinger Equation in Order to Solve for Transition Energies • Derivation of the Three-Dimensional Time-independent Schrödinger Equation • Extension of the Three-Dimensional Time-independent Schrödinger Equation to Wavevector Surfaces • Learning Objectives By the Conclusion of this Presentation, You Should be Able to: 1. Solve for the transition energy values in simple organic molecule systems using the Time-independent Schrödinger Equation. 2. Derive the three-dimensional, time-independent Schrödinger equation using the separation of variables method. 3. Convert between real space and wavevector space. The Energy of the Electron is a Function of the Quantum Number Recall from the Previous Lecture That the Following Holds for an Free Electron Contained within a Well with Walls at Infinite Potential Energy nπ ψ = n (x) sin (x) L n2h2 E = n 8mL2 Note That as the Quantum Number (n) increases, the energy increases. Furthermore, the “length of the box” plays an important role in the calculated energy. Estimating Energetic Transitions in Molecules Using This Model Example: The HOMO to LUMO Transition Energy in 1,3-Butadiene 1,3-Butadiene Assume that the Molecule is Linear 4 Carbons with sp2 Hybridized Orbitals (i.e., Do Not Consider Bond Angles) 2 C=C Double Bonds (0.135 nm): 0.270 nm 1 C-C Single Bond (0.154 nm): 0.154 nm 2 Carbon Radii (0.077nm): 0.154 nm 4 Frontier pz Orbitals for π-Bonding Summing These Values Gives L * π4 L = 0.578 nm * π3 n2h2 π E = or 2 n 8mL2 pz pz pz pz ( j 2 − i2 )h2 ∆ = Ei→ j 2 8me L π1 Further Reading: Physical Chemistry: A Molecular Approach by Donald A.