The Case of Italian Football

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

2016 Panini Flawless Soccer Cards Checklist

Card Set Number Player Base 1 Keisuke Honda Base 2 Riccardo Montolivo Base 3 Antoine Griezmann Base 4 Fernando Torres Base 5 Koke Base 6 Ilkay Gundogan Base 7 Marco Reus Base 8 Mats Hummels Base 9 Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang Base 10 Shinji Kagawa Base 11 Andres Iniesta Base 12 Dani Alves Base 13 Lionel Messi Base 14 Luis Suarez Base 15 Neymar Jr. Base 16 Arjen Robben Base 17 Arturo Vidal Base 18 Franck Ribery Base 19 Manuel Neuer Base 20 Thomas Muller Base 21 Fernando Muslera Base 22 Wesley Sneijder Base 23 David Luiz Base 24 Edinson Cavani Base 25 Marco Verratti Base 26 Thiago Silva Base 27 Zlatan Ibrahimovic Base 28 Cristiano Ronaldo Base 29 Gareth Bale Base 30 Keylor Navas Base 31 James Rodriguez Base 32 Raphael Varane Base 33 Karim Benzema Base 34 Axel Witsel Base 35 Ezequiel Garay Base 36 Hulk Base 37 Angel Di Maria Base 38 Gonzalo Higuain Base 39 Javier Mascherano Base 40 Lionel Messi Base 41 Pablo Zabaleta Base 42 Sergio Aguero Base 43 Eden Hazard Base 44 Jan Vertonghen Base 45 Marouane Fellaini Base 46 Romelu Lukaku Base 47 Thibaut Courtois Base 48 Vincent Kompany Base 49 Edin Dzeko Base 50 Dani Alves Base 51 David Luiz Base 52 Kaka Base 53 Neymar Jr. Base 54 Thiago Silva Base 55 Alexis Sanchez Base 56 Arturo Vidal Base 57 Claudio Bravo Base 58 James Rodriguez Base 59 Radamel Falcao Base 60 Ivan Rakitic Base 61 Luka Modric Base 62 Mario Mandzukic Base 63 Gary Cahill Base 64 Joe Hart Base 65 Raheem Sterling Base 66 Wayne Rooney Base 67 Hugo Lloris Base 68 Morgan Schneiderlin Base 69 Olivier Giroud Base 70 Patrice Evra Base 71 Paul -

Pepyhierro,Aescena Enelnuevoeldorado

Mundo Deportivo Jueves 9 de octubre de 2003 FUTBOL INTERNACIONAL 27 FLASH INTERNACIONAL Guerra Madaleno promete el regreso de Rui Costa El candidato a las elecciones del Benfica juega una carta 'a lo Florentino Pérez' y asegura que si sale elegido el día 31 el crack del Milan volverá ܘ J. C. Miranda Sólo una multa para Campbell El internacional del Arsenal pagará 31.250 euros por su conducta con Djemba Djemba (ManU) en la Community Shield ܘ Poyet piensa en la retirada El ex zaragocista y hoy en el Tottenham anunció que probablemente dirá adiós al fútbol a final de temporada, aunque la decisión no es definitiva ܘ Se reparten culpas en el Inter El presidente, Massimo Moratti, quien desde 1995 ha invertido 463 millones de euros en fichajes. dice que los Volverán a ser rivales Fernando Hierro y Pep Guardiola, charlando ayer en Qatar. Mañana debuta el ex azulgrana y el sábado lo hará el ex madridista en la Liga de este país FOTO: EPA jugadores deben asumir su responsabilidad y, para Cannavaro, la Hoy arranca la Liga de Qatar, plagada de veteranas estrellas fichadas a base de suculentos petrodólares mitad de la culpa es de Cüper ܘ Panucci, baja en Italia y Desailly, en Francia Trapattoni llamó a Pancaro. Santini, a Squillaci ܘ Pep y Hierro, a escena Dos puntos más para el Fluminense El Tribunal de Justicia Deportivo se los ha restado al Paysandú (y otros dos que han ido a parar a Sao Caetano), pero el 'Flu', en en el nuevo Eldorado el que hoy vuelve Romario tras dos meses parado, sigue penúltimo. -

Panini World Cup 2002 USA/European

www.soccercardindex.com Panini World Cup 2002 checklist □1 FIFA World Cup Trophy Costa Rica Nigeria Federation Logos □2 Official Emblem □44 Hernan Medford □82 JayJay Okocha □120 Argentina □3 Official Mascots □45 Paulo Wanchope □83 Sunday Oliseh □121 Belgium □84 Victor Agali □122 Brazil Official Posters Denmark □85 Nwankwo Kanu □123 China □4 1930 Uruguay □46 Thomas Helveg □124 Denmark □5 1934 Italia □47 Martin Laursen Paraguay □125 Germany □6 1938 France □48 Martin Jørgensen □86 Jose Luis Chilavert □126 France □7 1950 Brasil □49 Jon Dahl Tomasson □87 Carlos Gamarra □127 Croatia □8 1954 Helvetia □88 Roberto Miguel Acuna □128 Italy □9 1958 Sverige Germany □129 Japan □10 1962 Chile □50 Oliver Kahn Poland □130 Korea Republic □11 1966 England □51 Jens Nowotny □89 Tomasz Hajto □131 Mexico □12 1970 Mexico □52 Marko Rehmer □90 Emmanuel Olisadebe □132 Paraguay □13 1974 Deutschland BRD □53 Michael Ballack □133 Poland □14 1978 Argentina □54 Sebastian Deisler Portugal □134 Portugal □ □ □15 1982 Espana 55 Oliver Bierhoff 91 Sergio Conceicao □135 Saudi Arabia □ □ □16 1986 Mexico 56 Carsten Jancker 92 Luis Figo □136 South Africa □ □17 1990 Italia 93 Rui Costa □137 Sweden □ □18 1994 USA France 94 Nuno Gomes □138 Turkey □ □ □19 1998 France 57 Fabien Barthez 95 Pauleta □139 USA □ □20 2002 KoreaJapan 58 Vincent Candela □ Russia 59 Lilian Thuram □140 Checklist □ □96 Viktor Onopko Argentina 60 Patrick Vieira □ □21 Fabian Ayala □61 Zinedine Zidane 97 Alexander Mostovoi □ □22 Walter Samuel □62 Thierry Henry 98 Egor Titov □ □23 Kily Gonzalez □63 David Trezeguet -

Di Andrea Pirlo

WIKO SCENDE IN CAMPO COME MAIN SPONSOR PER “LA NOTTE DEL MAESTRO” DI ANDREA PIRLO Milano, 21/05/2018 – Wiko annuncia la sponsorship della partita di addio al calcio giocato di Andrea Pirlo, “La Notte del Maestro”, che tra poche ore riempirà lo stadio Giuseppe Meazza di Milano, dove sono attesi migliaia di fan e due formazioni stellari di sportivi che hanno scritto la storia del calcio, in Italia e all’estero. In qualità di main sponsor, Wiko sarà presente sulle maglie dei due team in campo, White Stars e Blue Stars, capitanati per l’occasione da Conte, Ancelotti, Allegri e Tassotti. Il brand Wiko sarà protagonista all’interno dello stadio anche sui maxischermi, sui led display a bordocampo, oltre che nell’arco che i giocatori attraverseranno per entrare in campo. Wiko avrà inoltre un palco d’eccezione posizionato accanto alla panchina dei giocatori, che offrirà una prospettiva unica agli ospiti. I fan di Wiko che non saranno presenti allo stadio, potranno seguire l’evento e sentirsi parte integrante di esso con #LussoDemocratico, lanciato in occasione dell’arrivo in Italia dei nuovi smartphone Wiko View 2 e View 2 Pro che, grazie al display da 19:9, garantiscono un’esperienza d’uso ancora più coinvolgente, ad un prezzo competitivo. A tutti coloro che saranno presenti a San Siro invece, Wiko ha riservato una sorpresa prima dell’ingresso allo stadio: gli spettatori saranno infatti accolti dai Wiko Ambassador, pronti a tatuargli sulla mano lo stesso simbolo apparso nei giorni scorsi sulla mano destra di Andrea Pirlo. Coincidenze? Assolutamente no. Si tratta della forma che contraddistingue View 2 e View 2 Pro, ben visibile dal notch tondo che racchiude la fotocamera frontale, e che Andrea ha reso virale sui social mentre stava definendo la formazione che avrebbe schierato in campo. -

Candidates Short-Listed for UEFA Champions League Awards

Media Release Route de Genève 46 Case postale Communiqué aux médias CH-1260 Nyon 2 Union des associations Tel. +41 22 994 45 59 européennes de football Medien-Mitteilung Fax +41 22 994 37 37 uefa.com [email protected] Date: 29/05/02 No. 88 - 2002 Candidates short-listed for UEFA Champions League awards Supporters invited to cast their votes via special polls on uefa.com official website With the curtain now down on the 2001/02 club competition season, UEFA’s Technical Study Group has produced short-lists of players and coaches in three different categories and will select a ‘Dream Team’ to mark the tenth anniversary of Europe’s top club competition, based on performances in the UEFA Champions League since it was officially launched in 1992. As usual, they have put forward nominees to receive the annual awards presented at the UEFA Gala, held as a curtain-raiser to the new club competition season at the end of August to coincide with the draws for the opening stages of the UEFA Champions League and the UEFA Cup. They have named six candidates for each of the awards presented to the Best Goalkeeper, Best Defender, Best Midfielder, Best Attacker, Most Valuable Player and Best Coach, based on their performances during the 2001/02 European campaign. This is not restricted to the UEFA Champions League – which explains the inclusion of Bert van Marwijk, head coach of the Feyenoord side which carried off the UEFA Cup and will be in Monaco to contest the UEFA Super Cup with Real Madrid CF. -

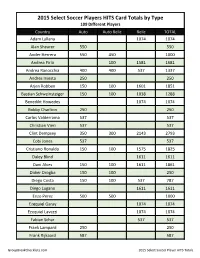

2015 Select Soccer Team HITS Checklist;

2015 Select Soccer Players HITS Card Totals by Type 109 Different Players Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Adam Lallana 1074 1074 Alan Shearer 550 550 Ander Herrera 550 450 1000 Andrea Pirlo 100 1581 1681 Andrea Ranocchia 400 400 537 1337 Andres Iniesta 250 250 Arjen Robben 150 100 1601 1851 Bastian Schweinsteiger 150 100 1038 1288 Benedikt Howedes 1074 1074 Bobby Charlton 250 250 Carlos Valderrama 537 537 Christian Vieri 537 537 Clint Dempsey 350 300 2143 2793 Cobi Jones 537 537 Cristiano Ronaldo 150 100 1575 1825 Daley Blind 1611 1611 Dani Alves 150 100 1611 1861 Didier Drogba 150 100 250 Diego Costa 150 100 537 787 Diego Lugano 1611 1611 Enzo Perez 500 500 1000 Ezequiel Garay 1074 1074 Ezequiel Lavezzi 1074 1074 Fabian Schar 537 537 Frank Lampard 250 250 Frank Rijkaard 587 587 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2015 Select Soccer Player HITS Totals Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Franz Beckenbauer 250 250 Gerard Pique 150 100 1601 1851 Gervinho 525 475 1611 2611 Gianluigi Buffon 125 125 1521 1771 Guillermo Ochoa 335 125 1611 2071 Harry Kane 513 503 537 1553 Hector Herrera 537 537 Hugo Sanchez 539 539 Iker Casillas 1591 1591 Ivan Rakitic 450 450 1024 1924 Ivan Zamorano 537 537 James Rodriguez 125 125 1611 1861 Jan Vertonghen 200 150 1074 1424 Jasper Cillessen 1575 1575 Javier Mascherano 1074 1074 Joao Moutinho 1611 1611 Joe Hart 175 175 1561 1911 John Terry 587 100 687 Jordan Henderson 1074 1074 Jorge Campos 587 587 Jozy Altidore 275 225 1611 2111 Juan Mata 425 375 800 Jurgen Klinsmann 250 250 Karim Benzema 537 537 Kevin Mirallas 525 475 -

CONF'in BREIZH N°8 – Corrections

#8 Samedi… JE LOCALISE JE CROISE JE CHALLENGE JE QUIZ Cliquez sur un département pour découvrir ce qui se cache derrière ! Samedi,.. ! JE LOCALISE L’Avenir Goëlo Les Goélands Plourivo de Plouézec Les Griffons Stade Briochin Les Paotred du Tarun St Brieuc La Chapelle-neuve Les Aiglons Les Crocos AS Ginglin Cesson RC Dinan St Brieuc Les Blaugranas Le FC du Lié Rostrenen FC Plouguenast #8 Samedi,.. ! JE QUIZ CULTURE FOOT « El Diez », « Pelusa », « El Pibe de Oro » étaient des surnoms donnés à Maradona 1/2 Argentine JEU DES SURNOMS Sauras-tu relier ces autres grands joueurs argentins avec leur surnom ? 1/ Lionel Messi --------------> H/ La Pulga (La Puce) 11/ Hernan Crespo ----------> F/ El Polaco (le Polonais) 3/ Angel Di Maria -----------> S/ El Fideo (Spaghetti) 12/ Gabriel Heinze ----------> C/ El Gringo (l’« Etranger ») 4/ Javier Saviola -------------> E/ El Conejito (Le petit Lapin) 13/ Javier Mascherano -----> L/ EL Jefecito (le Petit Chef) 5/ J. Roman Riquelme -----> I/ El Ultimo Diez (Le Dernier n°10) 14/ Javier Pastore ----------> D/ El Flaco (le Maigre) 6/ J. Sebastian Veron ------> T/ La Brujita (La Petite Sorcière) 15/ Diego Simeone ----------> K/ El Cholo (le « chef de gang ») 8/ Paulo Dybala -----------> B/ La Joya (Le Bijou) 16/ Sergio Aguëro ----------> J/ El Kun (référence) 9/ Gabriel Batistuta -------> O/ Batigol 17/ Carlos Tevez ----------> P/ El Apache (l’Apache) 18/ Gonzalo Higuain --------> A/ El Pipita (référence) #8 Samedi,.. ! JE QUIZ CULTURE FOOT 2/2 Argentine Parmi ces clubs, trouver les 5 clubs mythiques situés -

2017 Panini Nobility Soccer

2017 Panini Nobility Soccer Checklist by Country 21 Teams, 19 Teams with Autographs; Ireland/Mexico No Hits Green = HITS (autos, relics, auto/relics) ARGENTINA Print Player Set # Team Listed Run Diego Maradona Base 12 Argentina ?? + 378 Diego Maradona Base SP 94 Argentina ?? + 378 Diego Maradona Championship Caliber Insert + Parallels 12 Argentina ?? + 11 Diego Maradona For Club Insert + Parallels 8 Argentina ?? + 11 Diego Maradona And Country Insert + Parallels 8 Argentina ?? + 11 Diego Maradona Marquee Moments Insert + Parallels 1 Argentina ?? + 11 Diego Maradona Crescent Signatures 18 Argentina ?? + 61 Diego Milito Base 9 Argentina ?? + 378 Diego Simeone Base 45 Argentina ?? + 378 Diego Simeone Championship Caliber Insert + Parallels 29 Argentina ?? + 11 Diego Simeone Iconic Signatures 12 Argentina 31 Gabriel Batistuta Base 55 Argentina ?? + 378 Gabriel Batistuta Base SP 92 Argentina ?? + 378 Gabriel Batistuta Championship Caliber Insert + Parallels 26 Argentina ?? + 11 Gabriel Batistuta Marquee Moments Insert + Parallels 18 Argentina ?? + 11 Gabriel Batistuta National Heroes Insert+ Parallels 22 Argentina ?? + 11 Gabriel Batistuta Crescent Signatures 34 Argentina ?? + 61 Gabriel Batistuta Iconic Signatures 3 Argentina 31 Javier Zanetti Base 36 Argentina ?? + 378 Javier Zanetti For Club Insert + Parallels 6 Argentina ?? + 11 Javier Zanetti And Country Insert + Parallels 6 Argentina ?? + 11 Javier Zanetti Iconic Signatures 30 Argentina 231 Lionel Messi Base SP 99 Argentina ?? + 378 Lionel Messi For Club Insert + Parallels 10 Argentina -

Soccer Star Lionel Messi Kindle

SOCCER STAR LIONEL MESSI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Albert Torres | 48 pages | 01 Apr 2014 | Speeding Star | 9781622851102 | English | United States Soccer Star Lionel Messi PDF Book Association football portal Argentina portal. May Retrieved 18 June Diari Segre. The Rec. TN in Spanish. Archived from the original on 7 April Since , Messi has been in a relationship with Antonella Roccuzzo, a fellow native of Rosario. Argentina men's football squad — Summer Olympics — Gold medalists. Retrieved 19 June In eight qualifying matches under Maradona's stewardship, Messi scored only one goal, netting the opening goal in the first such match, a 4—0 victory over Venezuela. During the —04 season , his fourth with Barcelona, Messi rapidly progressed through the club's ranks, debuting for a record five youth teams in a single campaign. As his career advanced, and his tendency to dribble diminished slightly with age, Messi began to dictate play in deeper areas of the pitch , and developed into one of the best passers and playmakers in football history. Times Internet Limited. Former Barcelona defender Carles Puyol, who was captain and teammate to Messi, tweeted his support to the Argentine. Messi hasn't scored for Barca since the opening day of the season. His first goal was also his 10th league goal of the season, making him the first player ever to reach double figures in La Liga for 13 consecutive seasons. The Argentine forward drew his third consecutive blank in front of goal on Saturday as Barca lost to Getafe. Retrieved 20 February He has scored over senior career goals for club and country. -

UD World Cup 94

soccercardindex.com Upper Deck World Cup USA 1994 (1994 Contenders English/German) USA Brazil Norway 1 Tony Meola 49 Taffarel 93 Erik Thorstvedt 2 Des Armstrong 50 Jorginho 94 Gøran Sørloth 3 Marcelo Balboa 51 Branco 95 Rune Bratseth 4 Fernando Clavijo 52 RIcardo Rocha 96 Jan Åge Fjørtoft 5 John Doyle 53 Ricardo Gomes 97 Kjetil Rekdal 6 Alexi Lalas 54 Dunga 98 Erik Mykland 7 Thomas Dooley 55 Mauro Silva 99 Lars Bohinen 8 John Harkes 56 Rai 100 Øyvind Leonhardsen 9 Tab Ramos 57 Zinho 10 Hugo Pérez 58 Bebeto Switzerland 11 Cobi Jones 59 Romario 101 Adrian Knup 12 Chris Henderson 60 Muller 102 Stephane Chapuisat 13 Roy Wegerle 61 Palhina 103 Dominique Herr 14 Eric Wynalda 62 Cafu 104 Marc Hottiger 15 Cle Kooiman 63 Marcio Santos 105 Alain Sutter 16 Brad Friedel 64 Valdo 106 Georges Bregy 17 Ernie Stewart 107 Alain Geiger Sweden 108 Marco Pascolo Mexico 65 Thomas Ravelli 109 Regis Rothenbüler 18 Jorge Campos 66 Patrick Andersson 19 Claudio Suarez 67 Jan Eriksson Greece 20 Ramirez Perales 68 Klas Ingesson 110 Antonis Minou 21 Ignacio Ambriz 69 Anders Limpar 111 Stelios Manolsa 22 Ramon Ramirez 70 Stefan Schwarz 112 Anastasios Mitropoulos 23 Miguel Herrera 71 Jonas Thern 113 Yiotis Tsaloudhidis 24 David Patino 72 Tomas Brolin 114 Nikolaos Tsiantakis 25 Alberto Garcia Aspe 73 Martin Dahlin 115 Athanasios Kolitsidakis 26 Miguel España 74 Ronald Nilsson 116 Efstratios Apostolakis 27 Alex Garcia 75 Roger Ljung 117 Nikos Nobilas 28 Luis García 76 Stefan Rehn 118 Spiridon Maragos 29 Hugo Sánchez 77 Johnny Ekström Italy 30 Luis Miguel Salvador 78 -

SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES Bestseller International Bestseller

4color process, CMYK matte lamination + spot gloss (p.2) + emboss (p.3) SPORTS/SOCCER SOCCERNOMICS NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER INTERNATIONAL BESTSELLER “As an avid fan of the game and a fi rm believer in the power that such objective namEd onE oF thE “bEst booKs oF thE yEar” BY GUARDIAN, SLATE, analysis can bring to sports, I was captivated by this book. Soccernomics is an FINANCIAL TIMES, INDEPENDENT (UK), AND BLOOMBERG NEWS absolute must-read.” —BillY BEANE, General Manager of the Oakland A’s SOCCERNOMICS pioneers a new way of looking at soccer through meticulous, empirical analysis and incisive, witty commentary. The San Francisco Chronicle describes it as “the most intelligent book ever written about soccer.” This World Cup edition features new material, including a provocative examination of how soccer SOCCERNOMICS clubs might actually start making profi ts, why that’s undesirable, and how soccer’s never had it so good. WHY ENGLAND LOSES, WHY SPAIN, GERMANY, “read this book.” —New York Times AND BRAZIL WIN, AND WHY THE US, JAPAN, aUstralia– AND EVEN IRAQ–ARE DESTINED “gripping and essential.” —Slate “ Quite magnificent. A sort of Freakonomics TO BECOME THE kings of the world’s for soccer.” —JONATHAN WILSON, Guardian MOST POPULAR SPORT STEFAN SZYMANSKI STEFAN SIMON KUPER SIMON kupER is one of the world’s leading writers on soccer. The winner of the William Hill Prize for sports book of the year in Britain, Kuper writes a weekly column for the Financial Times. He lives in Paris, France. StEfaN SzyMaNSkI is the Stephen J. Galetti Collegiate Professor of Sport Management at the University of Michigan’s School of Kinesiology.