Koodankulam Anti-Nuclear Movement: a Struggle for Alternative Development?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Volga to Ganga : the Story of Kudankulam

From Volga to Ganga : The Story of Kudankulam Nu-Power golden beach Kovalam. The temple is a fine example of blend of the Kerala and Dravidian styles of architecture. The internationally renowned Kovalam beach resort, with its three adjacent crescent beaches, is a favorite tourist haunt. The National Highway No.47 (NH-47) connects Trivandrum and Kanyakumari, my sojourn en-route Kudankulam. The continuous habitats photo: A.I. Siddiqui The Padmanabhaswamy temple in along the high-way makes it difficult for Trivandrum the first time visitors to identify where India’s biggest nuclear power station one city ends and the next town begins. in being set-up at Kudankulam in But farther from Trivandrum, the rows collaboration with the Russian of houses gradually disappear Federation A.I. Siddiqui presents providing overwhelming views of paddy details in this travelogue-cum- fields, coconut grooves and banana technical feature plants all of which are closely integrated with the lives and culture of the people living in this region. The aerial view of Kanyakumari, named after Goddess Thiruvananthapuram, Trivandrum for Kanyakumari Amman, is about 80 kms short, is mesmerizing – presenting from Trivandrum. Kanyakumari, a small hues of green and blue. As the habitat in Tamil Nadu State, is a very aeroplane de- popular name among scends further, the Indians, as a pilgrim and verdant Kerala re- famous tourist spot. It veals its enthral- has the distinction of ling landscape. being the southern most The Trivandrum point of the mainland airport is comfort- India. Here, Bay of ably devoid of Bengal on one hand and clamours of hotel Arabian Sea on the other agents and taxi- meet the Indian Ocean, men. -

Conservation Status of Fish Species at Pechiparai Reservoir, Kanyakumari District of Tamil Nadu, India

52 JFLS | 2018 | Vol 3(1) | Pp 52-63 Research Article Conservation status of fish species at Pechiparai reservoir, Kanyakumari district of Tamil Nadu, India Sudhan, C*, Kingston, D., Jawahar, P., Aanand, S., Mogalekar, H.S. and Ajith Stalin Department of Fisheries Biology and Resource Management, Fisheries College and Research Institute, Tamil Nadu Fisheries University, Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu, 628008, India ABSTRACT ISSN: 2456- 6268 In the present investigation a total of 1844 fish specimens under 8 orders, 18 families and ARTICLE INFO 41 genera and 65 species were collected from Pechiparai reservoir. The systematic Received: 01 May 2018 checklist of fishes was prepared with note on common name, species abundance, habitat, Accepted: 20 June 2018 length range, human utilization pattern, current fishery status and global conservation Available online: 30 June 2018 status. The catch per unit effort was maximum during the month of June 2016 (0.4942 KEYWORDS kg/coracle/day) and minimum during the month of September 2016 (0.0403 Ichthyofauna, kg/coracle/day). The conservation status of fishes reported at Pechiparai reservoir were Conservation status Not evaluated for all 65 species by CITES; two species as Endangered (EN) and seven Endangered species as Vulnerable (VU) by NBFGR, India. The data obtained revealed one species as Pechiparai Endangered (EN), three species as Vulnerable (VU), seven species as Near Threatened Reservoir (NT), forty eight species as Least Concern (LC), one species as Data Deficient (DD) and Kanyakumari five species as Not Evaluated (NE) by IUCN. * CORRESPONDENCE © 2018 The Authors. Published by JFLS. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND [email protected] license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0). -

Approval of Ph.D Registration (Science)

APPROVAL OF PH.D REGISTRATION (SCIENCE) Name of the Guide and Address/ No. of Vacancy Discipline/ Research Educational Want of S.No. Candidates Name and Address Category Sex under the Guide/Co-Guide (Including this Centre Qualification Particulars Candidate) Mr. M. Muruganandam (Reg.No. 12524) Criminology and Dr. Beulah Shekhar - Guide 33-4A, Vairavi Street, Police Science – M. Associate Professor, 1 Krishna Puram, Full Time M M.A., M.Phil., S. University Dept. of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Kadayanallur, Tirunelveli. M.S.University, Tirunelveli. 4/6 Tirunelveli – 627 759. (M) 9976143343 TITLE : A STUDY OF VICTIM COMPENSATION FOR OFFENCES AGAINST HUMAN BODY IN THREE DISTRICTS (TIRUNELVELI, KANYAKUMARI AND TUTICORIN) Mr. L. Thanigaivel (Reg. No. 12507) Dr. Beulah Shekhar - Guide Criminology – M. S/o. G. Loganathan, Part Time Associate Professor, 2 S. University M M.A., M.Phil., No.70; Gandhi Road, External Dept. of Criminology and Criminal Justice, Tirunelveli. Trivellore (D.T)- 602 001.(M) M.S.University, Tirunelveli. 5/6 9443640888 TITLE : THE PROTECTION OF CHILDREN FROM SEXUAL OFFENCES ACT 2012 AND EVALUATION OF ITS IMPLEMENTATION IN TAMIL NADU Mrs. V. Seema (Reg. No. 12523) Botany – Dr. V. Manimekalai -Guide Pokkattu, Adinadu Sri Parasakthi College Asst. Professor of Botany, 3 North -P.O, Full Time F M.Sc., M.Phil for Women, Sri Parasakthi College for Women, Karunagappally, Courtallam. Courtallam 3/4 Kollam, Kerala – 690 542. TITLE : ANATOMICAL STUDIES ON MYRISTICA FRAGRANS HOUTT Ms. K.V. Gomathi (Reg. No. 12565) Information and Dr. S. Saudia -Guide Old No.114, New Communication Asst. Professor, No.54, Amman 4 Technologies – M.S. -

List of Applications for the Post of Office Assistant

List of applications for the post of Office Assistant Sl. Whether Application is R.R.No. Name and address of the applicant No. Accepted (or) Rejected (1) (2) (3) (5) S. Suresh, S/o. E.Subramanian, 54A, Mangamma Road, Tenkasi – 1. 6372 Accepted 627 811. C. Nagarajan, S/o. Chellan, 15/15, Eyankattuvilai, Palace Road, 2. 6373(3) Accepted Thukalay, Kanyakumari District – 629 175. C. Ajay, S/o. S.Chandran, 2/93, Pathi Street, Thattanvilai, North 3. 6374 Accepted Soorankudi Post, Kanyakumari District. R. Muthu Kumar, S/o. Rajamanickam, 124/2, Lakshmiyapuram 7th 4. 6375 Accepted Street, Sankarankovil – 627 756, Tirunelveli District. V.R. Radhika, W/o. Biju, Perumalpuram Veedu, Vaikkalloor, 5. 6376 Accepted Kanjampuram Post, Kanyakumari District – 629 154. M.Thirumani, W/o. P.Arumugam, 48, Arunthathiyar Street, Krishnan 6. 6397 Accepted Koil, Nagercoil, Kanyakumari District. I. Balakrishnan, S/o. Iyyappan, 1/95A, Sivan Kovil Street, Gothai 7. 6398 Accepted Giramam, Ozhuginaseri, Nagercoil – 629001. Sambath. S.P., S/o. Sukumaran. S., 1-55/42, Asarikudivilai, 8. 6399 Accepted Muthalakurichi, Kalkulam, Thukalay – 629 175. R.Sivan, S/o. S.Rajamoni, Pandaraparambu, Thottavaram, 9. 6429 Accepted Puthukkadai Post – 629 171. 10. S. Subramani, S/o. Sankara Kumara Pillai, No.3, Plot No.10, 2nd Main Age exceeds the maximum age 6432 Road, Rajambal Nager, Madambakkam, Chennai – 600 126. limit. Hence Rejected. R.Deeba Malar, W/o. M.Justin Kumar, Door No.4/143-3, Aseer Illam, 11. Age exceeds the Maximum Age 6437 Chellakkan Nagar, Keezhakalkurichi, Eraniel Road, Thuckalay Post – limit. Hence Rejected 629 175. 12. S. Anand, S/o. Subbaian, 24/26 Sri Chithirai Rajapuram, 6439 Accepted Chettikulam Junction, Nagercoil – 629 001. -

Kodaiyar River Basin

Kodaiyar River Basin Introduction One of the oldest systems in Tamil Nadu is the “Kodaiyar system” providing irrigation facilities for two paddy crop seasons in Kanyakumari district. The Kodaiyar system comprises the integrated operation of commands of two major rivers namely Pazhayar and Paralayar along with Tambaraparani or Kuzhithuraiyur in which Kodaiyar is a major tributary. The whole system is called as Kodaiyar system. Planning, development and management of natural resources in this basin require time-effective and authentic data.The water demand for domestic, irrigation, industries, livestock, power generation and public purpose is governed by socio – economic and cultural factors such as present and future population size, income level, urbanization, markets, prices, cropping patterns etc. Water Resources Planning is people oriented and resources based. Data relating to geology, geomorphology, hydrogeology, hydrology, climatology, water quality, environment, socio – economic, agricultural, population, livestock, industries, etc. are collected for analysis. For the sake of consistency, other types of data should be treated in the same way. Socio – economic, agricultural and livestock statistics are collected and presented on the basis of administrative units located within this basin area. Location and extent of Kodaiyar Basin The Kodaiyar river basin forms the southernmost end of Indian peninsula. The basin covers an area of 1646.964 sq km. The flanks of the entire basin falls within the TamilnaduState boundary. Tamiraparani basin lies on the north and Kodaiyar basin on the east and Neyyar basin of Kerala State lies on the west. This is the only river basin which has its coastal border adjoining the Arabian sea, the Indian Ocean in the south and the Gulf of Mannar in the east. -

ECO ‒ TOURISM SITE Tamil Nadu Biodiversity Conservation And

ECO – TOURISM SITE Tamil Nadu Biodiversity Conservation and Greening Project 1. Name of the Site : Sasthakoil 2. Name of District : Virudhunagar : Rajapalayam range / Srivilliputhur Wildlife Name of Range/ Division/ 3. Division/ Virudhunagar Circle Circle : Sasthakoil is located 24 km away from 4. Location Rajapalayam town. Nearest Bus stand with Rajapalayam, 24 Km 5. distance Nearest Railway station with : Rajapalayam, 24 Km 6. distance 7. Nearest Airport with distance : Madurai, 96 Km : 1. This site is located inside the sanctuary 2. Seasonal river named as nagariyar river flowing in the site. It is also called as Sasthakoil falls by the local people. 3. Very old idols of Ayyappas diety in present in a open space in the site. It is believed as family god for local people. 8. Characteristics of the site 4. Presence of Deciduous forest at lower elevation.Reverline forest along stream and semi evergreen forest at higher elevations. 5. One watch tower is existing in the site. 6. One Anti-poaching Shed is existing near temporary Check post. : Nanjadai Thavirthuliya Swamy temple 9. Tourist Attraction (Places) Nanjadai Thavirthuliya Swamy temple was constructed by King Pandiyas and it is at 3 km from Sasthakoil site outside of the sanctuary.. This temple is a very famous temple in the surroundings. Ayyanar temple Ayyanarkoil temple is very popular temple in this area. It is located 34 Km away from this site. It is extended site of the Sasthakoil Eco Tourism site in Rajapalayam range : Trekking facilities are available on amount of Rs. 250/ head collected for 4 km Trekking Sasthakoil to Mamarathukeni Mobile toilet facilities are available 10. -

Individual Biodata Name : Dr. S.David Kingston Designation

Individual Biodata Name : Dr. S.David kingston Designation : Professor and Head Address : Dept. of Fisheries Biology and Resource Management, Fisheries College and Research Institute, TNJFU, Thoothukudi- 628 008 Contact Telephone (O) : +91 2340554 Telephone (R) : Mobile : +91 9443446923 Email : [email protected] Qualification : M.F.,Sc., Ph.D, Field of Specialization : Fisheries Biology and Resource Management Major : Fisheries Biology and Resource Management Specializing field : Fish Biodiversity, River ecology and conservation Experience (in years) : 31 years Current projects : Sl.No. Title of the Project Year PI & Co- PI Funds Funding of the Project (in Rs) Agency 1. Assessment of 2017- Co-principal 21.00 NAFCC fishing pattern and 2018 Investigator Project. fishing pressure in Gulf fo Mannar coast. Completed projects : Sl.No. Title of the Project Year PI & Co- PI Funds Funding Agency of the Project (in lakh Rs) 1. Creation of 2003 Principal 4.00 District Rural infrastructure facilities Investigator Development in the newly Agency, established Veterinary Nagercoil, University Training Kanyakumari and Research Centre District at Parakkai, Kanyakumari District. 2. Conduct of Training 2007-2010 Principal 10.60 DBT, New Delhi on value added fish Investigator. products for Tsunami affected fisherwomen of Kanyakumari District of Tamil Nadu 3. Empowerment of 2012 to Principal 13.23 DBT, New Delhi SC/ST population of 2015 Investigator Kanyakumari district through adoption of ornamental fish culture practices 4. Mass breeding and 2013 to Principal 118.00 NADP, New Delhi production and 2015 Investigator. production of ornamental fishes and major carp seeds. : Research Publication. 1. Prateek, David Kingston.S. Mogalekar, H.S. Francis T, Aanand,S and Malay Biswas, (2015) Fish diversity of downstream waters of Pechiparai Reservoir in the Kanyakumari region of Western Ghats, Tamil nadu, J.Aqua Trop. -

District Survey Report for Limekankar Tirunelveli District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR LIMEKANKAR TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT 2019 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT-TIRUNELVELI 1 1. INTRODUCTION In conjunction to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the Government of India Notification No.SO 3611 (E) dated 25.07.2018 and SO 190 (E) dated 20.01.2016 the District Level Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) and District Environment Appraisal Committee (DEAC) were constituted in Tirunelveli District for the grant of Environmental Clearance for category “B2” projects for quarrying of Minor Minerals. The main purpose of preparation of District Survey Report is to identify the mineral resources and develop the mining activities along with relevant current geological data of the District. The DEAC will scrutinize and screen scope of the category “B2” projects and the DEIAA will grant Environmental Clearance based on the recommendations of the DEAC for the Minor Minerals on the basis of District Survey Report. This District Mineral Survey Report is prepared on the basis of field work carried out in Tirunelveli district by the official from Geological Survey of India and Directorate of Geology and Mining, (Tirunelveli District), Govt. of Tamilnadu. Tirunelveli district was formed in the year 1790 and is one of the oldest districts in the state, with effect from 20.10.1986 the district was bifurcated and new district Thothukudi was formed carving it. Tirunelveli district has geographical area of 6759 sq.km and lies in the south eastern part of Tamilnadu state. The district is bounded by the coordinates 08°05 to 09°30’ N and 77°05’ to 78°25 E and shares boundary with Virudunagar district in north, Thothukudi district in east, Kanniyakumari district in south and with Kerala state in the West. -

Tirunelveli District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR ROUGH STONE TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT TIRUNELVELI DISTRICT 2019 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT-TIRUNELVELI 1 1. INTRODUCTION In conjunction to the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the Government of India Notification No.SO 3611 (E) dated 25.07.2018 and SO 190 (E) dated 20.01.2016 the District Level Environment Impact Assessment Authority (DEIAA) and District Environment Appraisal Committee (DEAC) were constituted in Tirunelveli District for the grant of Environmental Clearance for category “B2” projects for quarrying of Minor Minerals. The main purpose of preparation of District Survey Report is to identify the mineral resources and develop the mining activities along with relevant current geological data of the District. The DEAC will scrutinize and screen scope of the category “B2” projects and the DEIAA will grant Environmental Clearance based on the recommendations of the DEAC for the Minor Minerals on the basis of District Survey Report. This District Mineral Survey Report is prepared on the basis of field work carried out in Tirunelveli district by the official from Geological Survey of India and Directorate of Geology and Mining, (Tirunelveli District), Govt. of Tamilnadu. Tirunelveli district was formed in the year 1790 and is one of the oldest districts in the state, with effect from 20.10.1986 the district was bifurcated and new district Thothukudi was formed carving it. Tirunelveli district has geographical area of 6759 sq.km and lies in the south eastern part of Tamilnadu state. The district is bounded by the coordinates 08°05 to 09°30’ N and 77°05’ to 78°25 E and shares boundary with Virudunagar district in north, Thothukudi district in east, Kanniyakumari district in south and with Kerala state in the West. -

The Role of Church and Western Ngos in Destabilization Activities in India by Ravindranath

The role of church and western NGOs in destabilization activities in India By Ravindranath There is a misconception that only the Muslim radicals resort to terrorism. However, the truth is that the Christian evangelists are equally guilty of encouraging terrorism in India. The only difference is that they do it in a surreptitious manner. In fact, the Christian involvement in aiding various insurgent and militant groups in the north-east started right from the time of India‟s emergence as an independent nation in 1947. The Christian missionaries, especially those belonging to Catholic and Protestant factions, are also found closely linked with pro-LTTE elements in Tamil Nadu, militant tribal groups in Tripura and the Maoist movement. It may be recalled that four RSS Pracharaks who were opposed to the Christian conversion activities in Tripura were abducted by a Christian militant group about 20 years back, and even their dead bodies were never recovered. Even now there are various instances of pro-Christian militants in Tripura intimidating the Hindu tribals against offering prayers at their religious places and disrupting their pujas and other religious rituals. It is an open secret that the church had used the Maoist outfit to eliminate VHP leader Swami Laxmanananda Saraswati and four others in Kandhamal district of Orissa on August 23, 2008, because of his opposition to the Christian conversion activities in the area. In an interview published in the May 6, 2010 edition of „Sathyadeepam‟, a Catholic weekly published from Kochi (Kerala), Bishop Charles Soreng of Hazaribagh, Jharkhand has admitted that the Maoists are sympathetic to the church and are supporting the priests in carrying out their missionary activities. -

Polling Station List-2021 ENGLISH.Xlsx

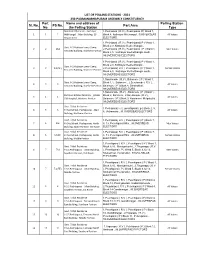

LIST OF POLLING STATIONS - 2021 232-PADMANABHAPURAM ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY Part Name and address of Polling Station Sl. No. PS No. Part Area No. the Polling Station Type Manmakil Mantram, Kothaiyar 1.Pechiparai ( R.V ), Peachiparai (P) Ward 1, 1 1 1 Melthangal ,Main Building, EB Block 4, Kothaiyar Melthangal , 99.OVERSEAS All Voters Department ELECTORS 1.Pechiparai ( R.V ), Peachiparai( P ) Ward 1, Block 2,3 ,Kothaiyar Kezhelthangal , Govt. H.S.Kodayar Lower Camp, 2 2 2M 2.Pechiparai ( R.V ), Peachiparai ( P ) Ward 1, Men Voters Terraced Building, Northern Portion Block 4,5, Kothaiyar Kezhelthangal south , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS 1.Pechiparai ( R.V ), Peachiparai( P ) Ward 1, Block 2,3 ,Kothaiyar Kezhelthangal , Govt. H.S.Kodayar Lower Camp, 3 2 2A(W) 2.Pechiparai( R.V ), Peachiparai ( P ) Ward 1, Female Voters Terraced Building, Southern Portion Block 4,5, Kothaiyar Kezhelthangal south , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS 1.Surulacode ( R.V ), Balamore ( P ) Ward 1, Govt. H.S.Kodayar Lower Camp, Block 1,4, Balamore , 2.Surulacode ( R.V ), 4 3 3 All Voters Terraced Building, Northern Portion Balamore ( P ) Block 4, Sambakkal , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS 1.Surulacode ( R.V ) , Balamore ( P ) Ward 1, Karimoni Estate Karimoni ,Estate Block 2, Karimoni , 2.Surulacode ( R.V ), 5 4 4 All Voters Old Hospital, Western Portion Balamore ( P ) Block 3, Kaarimoni Melpakuthi , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS Govt. Tribal Residence 1.Pechiparai( r.v ), peachiparai ( p ) Block 2, 5, 6 5 5 Hr.Sec.School, Pechipparai ,Main All Voters 6, Vizhamalai , 99.OVERSEAS ELECTORS Building, Northern Portion Govt. Tribal Residence 1.Pechiparai( R.V ), Peachiparai ( P ) Block 7, 7 6 6M Hr.Sec.School, Pechipparai, North 8, 13, Peachiparai Hills , 99.OVERSEAS Men Voters Building, South Portion First Room ELECTORS Govt. -

Officers and Staff Associated with This Publication

OFFICERS AND STAFF ASSOCIATED WITH THIS PUBLICATION Overall Guidance Dr. Atul Anand, I.A.S., Commissioner Department of Economics and Statistics TECHNICAL GUIDANCE Dr. B. Hariharadhas, M.Sc.,M.Phil.,Ph.D., Regional Joint Director of Statistics, Tirunelveli Thiru. P. Gomudurai Pandian, M.Sc., B.Ed., Deputy Director of Statistics, Nagercoil DATA PROCESSING Thiru.V. Karthigeyan, M.A., Statistical officer Tmt. B. Meena, B.Sc., Statistical Inspector Selvi. G. Jeba Jenifa, B.E., Data Coordinator PREFACE The District Statistical Hand Book is prepared and published by our Department every year. This book provides useful data across various departments in Kanniyakumari District. It contains imperative and essential statistical data on different Socio-Economic aspects of the District in terms of statistical tables and graphical representations. This will be useful in getting a picture of Kanniyakumari’s current state and analyzing what improvements can be brought further. I would liketo thank the respectable District Collector Prashant M.Wadnere, IASfor his cooperation in achieving the task of preparing theDistrict Hand Book for the year 2018-19and I humbly acknowledge his support with profound gratitude. The co-operation extended by the officers of this district, by supplying the information presented in this book is gratefully acknowledged. I express my appreciation for the effort taken by the district statistical unit in compilation and computerisation of this publication. I would be glad to welcome your valuable suggestions for improving the publication. Place : Kanniyakumari Deputy Director of Statistics , Date : 31-10-2019 Nagercoil INDEX Page No STATISTICAL TABLES CONTENTS Salient Features of Kanniyakumari District 1-12 District Profile 2018-19 13-30 1.