John Lynch of Galway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX. Have Extensive Schools Also Here

738 .HISTOBY . OF LIMERICK. projected, from designs by 5. J. M'Carthy, Esq., Dublia, by the Very Rev. Jsmes O'Shea, parish priest, and the parishioners. The Sister of Mercy have an admirable convent and school, and the Christian Brothers APPENDIX. have extensive schools also here. s~a~s.-Rathkede Abbey (G. W: Leech, Esq.), Castle Matrix, Beechmount (T. Lloyd, Esq , U.L.), Ba1lywillia.m (D. Mansell, Esq.), and Mount Browne (J. Browne, Ey.) There is a branch of the Provincial Bank of Ireland, adof the National PgqCJPhL CHARTERS OF LIMERICK, Bank of Ireland here. Charter granted by John ... dated 18th December, 1197-8 . ,, ,, Edward I., ,, 4th February, 1291 ,, ,, ,, Ditto ,, 6th May, 1303 ,, ,, Henry IV. ,, 26th June, 1400 ,, ,, Henry V. ,, 20th January, 1413 The History of Limerick closes appropriately with the recognition by ,, ,, ,, Henry VI. ,, 27th November, 1423 the government of Lord Palmerston, who has since been numbered ~6th ,, ,, ,, Ditto, ,, 18th November, l429 ,. ,, ,, Henry VI., ,, 26th July, 1449 the dead, of the justice and expediency of the principle of denominational ,, ,, ,, Edward VI. ,, 20th February, 1551 education, so far at least as the intimation that has been given of a liberal ,, ,, ,, Elizabeth, ,, 27th October, 1575 modification of the Queen's Culleges to meet Catholic requirements is con- ,, ,, ,, Ditto, ,, 19th March, 15b2 , Jrrmes I. ,, 8d March, 1609 cerned. We have said appropriately", because Limerick was the first Amsng the muniments of the Corporation is an Inspex. of Oliver Cromwell, dated 10th of locality in Ireland to agitate in favour of that movement, the author of February, 1657 ; and an Inspex. of Charles 11. -

Initial Reports Show $60,000 in Pledges As Church Starts

Page Eight THB BRAWypRD BEVIIiW • BAST HAVgIT HEWB •niuriJaY, Oefeber W. I?S0 4^0^!^leat^nm,^0,m0lmm^^Jtm> t. •\,u\^ii^^^^^»0tit*$0t0mt»mam0mi0>miMlm»0t^»0t0timMmii0*>t>»f^»i!t^^ HiiOiU^.N i'JSl.Oiili.L LIDiuaxY .f:T n..vF,n, OT. WHAT EAST HAVEN BOOSTS BOOSTS EAST HAVEN! r MAKE EAST HAVEN A BIGGER, ' .i',;«^ •! ' , BEHER. BUSIER COMMUNITY Combined With The Branford Review VpL. VII—NO. 7 EAST HAVEN, CONNECTICUT THURSDAY, OCTOBER 26, 1950 B Canfs Pop Copy—Two Dollari A Year .; }' r INITIAL REPORTS SHOW United Nations SOUTH END CIVIC ASS'N Town Tax Office ( •rf $60,000 IN PLEDGES AS Day Gets Full HELPS SCHOOL PROGRAM Readies List Of Tax Delinquents Numerous Halloween parlies slat CHURCH STARTS DRIVE Recognition WITH PLAYGROUND GIFT ,..-^' ed lor the lorthnlght the South The East Haven Tax Office Is End Civic Association Dinner Dance Members of the Old Stone Church last Sunday apiM-eciatlon gifts were A big step In ellmlnallng the con-' Russell Frank, the executive of currently preparing a list ot aulo United Nations Day was observed fusion in building a new school In ^ fleer of the Association said that leading the Held. Event takes place In East Haven were enthusiastic' tendered Bill Hasse, Curt Schu- at the High School on Tuesday, tax delinquents, which will be sent In Annex House on Saturday night thls week over the possibilities of macher and Mrs, Fletcher, the South End District was appar the vote carried 00 to 7 In favor of to the Motor Vehicle Commissioner October 24. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 1 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Abstract This study explores, reconstructs and evaluates the social, political, educational and economic worlds of the Irish Catholic episcopal corps appointed between 1657 and 1829 by creating a prosopographical profile of this episcopal cohort. The central aim of this study is to reconstruct the profile of this episcopate to serve as a context to evaluate the ‘achievements’ of the four episcopal generations that emerged: 1657-1684; 1685- 1766; 1767-1800 and 1801-1829. The first generation of Irish bishops were largely influenced by the complex political and religious situation of Ireland following the Cromwellian wars and Interregnum. This episcopal cohort sought greater engagement with the restored Stuart Court while at the same time solidified their links with continental agencies. With the accession of James II (1685), a new generation of bishops emerged characterised by their loyalty to the Stuart Court and, following his exile and the enactment of new penal legislation, their ability to endure political and economic marginalisation. Through the creation of a prosopographical database, this study has nuanced and reconstructed the historical profile of the Jacobite episcopal corps and has shown that the Irish episcopate under the penal regime was not only relatively well-organised but was well-engaged in reforming the Irish church, albeit with limited resources. By the mid-eighteenth century, the post-Jacobite generation (1767-1800) emerged and were characterised by their re-organisation of the Irish Church, most notably the establishment of a domestic seminary system and the setting up and manning of a national parochial system. -

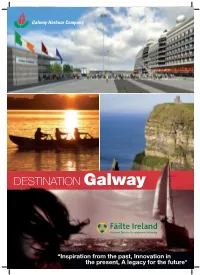

Destination Galway

DESTINATION Galway “Inspiration from the past, Innovation in the present, A legacy for the future” Fiona Monaghan Head of Operations Fáilte Ireland West Region Eamon Bradshaw Chief Executive Galway Harbour Company Fáilte Céad Míle Fáilte go Gaillimh agus A most sincere welcome to all our Iarthar Eireann. visitors to Galway City, the City of Welcome to Galway and the West the Tribes. of Ireland. In Galway you will find a race of people that warmly welcomes you to our city and the West of Ireland. It is Galway – a medieval City located on the shores a medieval city that easily embraces the past with a Galway Bay where the Corrib Lake meets the wild modern vibrant outlook. Situated on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean boasts a proud maritime history & Atlantic Ocean it is nevertheless the fastest growing culture dating back centuries. city in Western Europe. The city and surrounding areas are renowned for their natural unspoiled beauty. Be Galway City also known as the City of the Tribes is the sure and browse through the narrow streets of the gateway to some of the most dramatic landscapes city, talk to the people, visit the awe-inspiring Cliffs in the world – Connemara, the Aran Islands and the of Moher, taste the wild and beautiful scenery of Burren - home to iconic visitor attractions including Connemara or spend an afternoon on the mystical Kylemore Abbey & Walled Garden in Connemara, Dun Aran Islands. Aengus Fort on Inis Mór and the Cliffs of Moher in the Burren region. There are many hidden gems to savor during your visit not to mention a host of sporting opportunities, A bilingual city where our native Irish language is culinary delights, the traditional music pubs, the many interspersed with English, Galway offers visitors a festivals for which Galway is famous, the performing unique Irish experience with a rich history and a vibrant arts in all their Celtic traditions, visits to medieval modern culture. -

The Irish Catholic Episcopal Corps, 1657 – 1829: a Prosopographical Analysis

THE IRISH CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPS, 1657 – 1829: A PROSOPOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS VOLUME 2 OF 2 BY ERIC A. DERR THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERISTY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH SUPERVISOR OF RESEARCH: DR. THOMAS O’CONNOR NOVEMBER 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... i Abbreviations .................................................................................................................... ii Biographical Register ........................................................................................................ 1 A .................................................................................................................................... 1 B .................................................................................................................................... 2 C .................................................................................................................................. 18 D .................................................................................................................................. 29 E ................................................................................................................................... 42 F ................................................................................................................................... 43 G ................................................................................................................................. -

The Mcgrath Family of Truxton 01

The McGrath Family of Truxton, New York Michael F. McGraw 9108 Middlebie Drive Austin, TX 78750 [email protected] March 13, 2002 © Michael F. McGraw 2002 All rights reserved No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without prior written permission of the copyright owner. 2 Cover: The picture on the front cover was taken from the rear of the main lodge of the Labrador Mountain Ski Lodge facing in a northeasterly direction. It was probably taken in the last few years. The lodge itself is located across the road from a small cemetery that is marked by a cross on the 1876 map of Truxton below. The road running north and south, passing by the front of the lodge and extending left and right through the center of the picture, is the North Road. Following this road, also known as Route 91, to the right leads into the village of Truxton about 2 miles south of this location. The significance of this location is that the McGraws and many of their friends and relatives lived in this immediate area. Michael McGraw’s farm on the North Road was located one mile south and across the road from his farm was the John Casey farm. The region out in the flat area over the silo to the left was where John McGraw, Michael’s brother, was living in 1883. His neighbor moving south was Patrick Comerford, brother of his wife Ellen Comerford McGraw. -

Walking Whid/ Walking Story Oein Debharduin, Inaugural Recipient of the Thinking on Tuam Residency Walking Whid - a Culture Night 2020 Event

Walking Whid/ Walking Story Oein DeBharduin, inaugural recipient of the Thinking on Tuam residency Walking Whid - a Culture Night 2020 event Hello my name is Oein DeBhairduin, I am the current holder of the ‘Thinking on Tuam’ residency and this is the Walking Whid, the Walking Story of Tuam, brought to you by the kind support of Creative Places Tuam. In the bronze age era, approximately 1500 B.C. it is believed that there was a gravel burial ground located near the River Nanny, at a site close to the bridge of present day shop street. This large burial mound was also accompanied by a natural hill, that still exists today as Tullindaly hill. It is thought by many that this is where Tuam got its name, that of Tuaim Da Ghualann or ‘the tumulus of the two shoulders’. However this definition is disputed by some, who feel the title did not rise from these ‘two shoulders’ but two other hills, which also host a wide array of ancient sites, known as Knockma or Castlehacket which exist on the lands west of Tuam. Officially the town can trace its history back to 526 A.D. when Saint Jarlath, a noble man and priest of the local kingdom, set out, by the instruction of St Benan to leave the monastery of Cloonfush and set up a new school and monestry where ever his chariot wheel broke. Saint Jarlath must have been delighted at the wheel breaking at Tuam, not only were the grounds fertile and the river unprone, to flooding it was only 4 kilometres from Cloonfush. -

Kirby Catalogue Part 6 1880-1886

Archival list The Kirby Collection Catalogue Irish College Rome ARCHIVES PONTIFICAL IRISH COLLEGE, ROME Code Date Description and Extent KIR / 1880/ 2 1 January Holograph letter from T. J. O'Reilly, St. Mary's, 1880 Marlborough St., Dublin, to Kirby: Notification of collection in Archdiocese of Dublin to relieve the needy down the country. Requests that Holy See contribute if possible. 4pp 3 2 January Holograph letter from Peter Doyle, Rome, to Kirby: Thanks 1880 for gift of painting. 1p 4 3 January Holograph letter from Privato del Corso Sec. Inferiore, 1880 Palazzo Massimo, Rome, to Kirby: Invitation to see Crib. 1p 5 4 January Holograph letter from John Burke, Charleville, Co. Cork, to 1880 Kirby: Discussing his vocation to priesthood. 4pp 6 5 January Holograph letter from William Murphy, Hotel de l'Europa, 1880 Rome, to Kirby: Request for audience at Vatican. 4pp 7 5 January Holograph letter from +P. Moran, Kilkenny, to Kirby: 1880 Deals with threat of the Christian Brothers to leave Ireland and the method of presenting the case in Rome. 4pp 8 5 January Holograph letter from +G. McCabe, Kingstown, Co. 1880 Dublin, to Kirby: Deals with the threat of Christian Brothers to leave Ireland, giving writer's opinion as being that of many of the Irish Bishops. Bishops have appealed to Rome. They should not be allowed to get their money by this threat. He personally has been always friendly with them. 8pp 9 5 January Holograph letter from A. R. Reynolds, Philadelphia, 1880 U.S.A., to Kirby: Sends cash. Thanks, congratulations, general gossip. -

Gender, Nation, and the Politics of Shame: Magdalen Laundries and the Institutionalization of Feminine Transgression in Modern Ireland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by LSE Research Online Clara Fischer Gender, nation, and the politics of shame: Magdalen laundries and the institutionalization of feminine transgression in modern Ireland Article (Published version) (Refereed) Original citation: Fischer, Clara (2016) Gender, nation, and the politics of shame: Magdalen laundries and the institutionalization of feminine transgression in modern Ireland. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 41 (4). pp. 821-843. ISSN 0097-974 DOI: 10.1086/685117 © 2016 The University of Chicago This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/67545/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. Clara Fischer Gender, Nation, and the Politics of Shame: Magdalen Laundries and the Institutionalization of Feminine Transgression in Modern Ireland All of us know that Irish women are the most virtuous in the world. —Arthur Griffith, founder of Sinn Fe´in, 19031 The future of the country is bound up with the dignity and purity of the women of Ireland. -

Tuam Award Handbook

Pope John Paul II Award Award Handbook Contents Message from the Archbishop 1 Pope John Paul II Award 2 Who is the Award for? 3 How does the Award work? 4 Parish Involvement 6 Social Awareness 7 Presentation 8 Award Top-Ups 9 Code of Ethics 10 Offices 12 Pope John Paul II Award Message from the Archbishop It is sometimes said that our young people are the I thank the Knights of St. Columbanus for their Church of tomorrow and so they are. But young generous sponsorship of this project and I people are more than just the future of the Church. commend the Diocesan Youth Council for its They are the Church of today. As such, as well as energy and vision. Finally I pray God’s blessing on presenting us with our greatest resource, young all who will benefit from their involvement in the people also provide us with our greatest challenge. Pope John Paul II Awards. From chatting with young people from all over our + Michael Neary diocese I am convinced that many want to be Archbishop of Tuam involved in our Church. We, as a Church, need to offer young people real and meaningful opportunities to play their part in the building up of God’s kingdom. Tuam Diocesan Youth Council was formed in early 2008 and it continues to imagine new ways of engaging with the young people of our diocese. The setting up of the Pope John Paul II Award is a way of honouring the vital role which many young people already play in their parish communities. -

Lynch Family

LYNCH FAMILY OF EKGLAND AND TTIEL1\KD Iii Page 3, OCCGS Llbrary Additions, October, 1983 OBITUARIES Conti.nued San Diego County, CA Barbara A. Fant, Reg. 11 Oct. 198.3 KDthryri Stone Black I, TH E · LYN C H COAT-OF-ARM S HIS COAT-OF-ARMS was copied from the Records of H eraldry. G alway, Ireland, by Mr. M . L. Lynch. of T yler, Texas. Chief Engineer of the St. Louis & Sou th western R ailway System, who vouches for its authenticity. Mr. Lynch, a most estimable and honorable gentleman, is a civil en- , ,' gineer of exceptional reputation and ability, and made this copy with the strictest attention to det:1il. The reproduction on this sheet is pronounced by Mr. Lynch to be a perfect fae-simile, faithful alike in contour and color to the original copy on file in the arehilr.es of the City of Galway. OSCAR LYNCH. •:• miser able extremi ty of subsisting on the common ••• h Historical Sketch of the Lynch Family. ·!· erbage of the field, he was fi nally victorious. His •i• prince, amongst other rewards of his valor, presented ::: him with the Trefoil on ... a F ield of Azure for his FROM HARDEMAN'$ HISTORY GALWAY :~: arms and the Lynx, the sharpest sighted of all PAGE 17, DATE 1820. :~: animals, for his crest; the former in a llusion to the "Tradition and documents in possession of the •:• extremity to which he was drawn for subsistence family, which go to prove it, states that they wer e ::: during the siege, and the latter to his foresight and originally from the City of Lint.fl, the capital of + vigilance; and, as a testimon ial of his fidelity, he upper Austria, from which they suppose the name ::: also received the motto, SEMPER FIDELIS, which to have been derived; and that they are descended :~: arms, crest and motto are borne by the Lynch from Charlemagne, the youngest son of the emperor •.• family to this day. -

Global Education Office the College of William & Mary

Global Education Office Reves Center for International Studies The College of William & Mary PHOTO COURTESY OF CARA KATRINAK GALWAY SUMMER HANDBOOK Table of Contents Galway 2017 .............................................................................................. 3 Handy Information .................................................................................... 4 Overview, Dates, and Money .................................................................... 5 Visa Information and Budgeting ............................................................... 6 Packing ...................................................................................................... 9 Traveling to Galway................................................................................. 12 Coursework ............................................................................................. 13 Excursions & Activities ............................................................................ 15 Housing and Meals .................................................................................. 16 Communication ....................................................................................... 17 Health & Safety ....................................................................................... 18 Travel & Country Information ................................................................. 19 Galway ..................................................................................................... 20 FOR FUN: LIGHT READING AND MOVIES