2 Corinthians David E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul, Moses, and the History of Israel: the Letter/Spirit Contrast and the Argument From

Paul, Moses, and the History of Israel: The Letter/Spirit Contrast and the Argument from Scripture in 2 Corinthians 3. By Scott J. Hafemann. Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament. II/81. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1995, xii + 497 pp., DM 228. This work represents the completion of Hafemann's study on 2 Corinthians 2-3, and fortunately his book is also available in an affordable version from Hendrickson publishers. The first work is contained in his 1986 dissertation, Suffering and the Spirit, which was also published by J. C. B. Mohr in the WUNT series (an abridged and edited version of this book titled Suffering and Ministry in the Spirit is available from Eerdmans, 1990). Hafemann tackles one of the most controverted texts in the pauline corpus (2 Corinthians 3), and his study and conclusions are bound to be of interest since one's understanding of 2 Corinthians 3 impinges on central issues in pauline theology, such as Paul's understanding of the Mosaic law and the hermeneutical implications of his use of the Old Testament. Indeed, from now on all scholars who address these issues must reckon with Hafemann, for his work represents the most thorough interpretation both of 2 Corinthians 3 and the Old Testament background to that text, and he directly challenges the scholarly consensus on this text. The work commences with an introduction in which the history of research on the letter and spirit in Paul and the "new perspective" on Paul's theology of the law are sketched in. Part one of the book examines the sufficiency and call of Moses and the sufficiency and call of Paul. -

Studies in the Book of 2 Corinthians PART FOUR: Weeks 24-31 Group Applications Personal Study Week 24 2 Corinthians 10:1-6 (ESV)

Weak is STRONG Studies in the book of 2 Corinthians PART FOUR: Weeks 24-31 Group Applications Personal Study Week 24 2 Corinthians 10:1-6 (ESV) , Paul, myself entreat you, by the walk in the flesh, we are not waging war meekness and gentleness of Christ—I according to the flesh. 4 For the weapons who am humble when face to face with of our warfare are not of the flesh but have Iyou, but bold toward you when I am divine power to destroy strongholds. 5 We away!— 2 I beg of you that when I am destroy arguments and every lofty opinion present I may not have to show boldness raised against the knowledge of God, and with such confidence as I count on showing take every thought captive to obey Christ, 6 against some who suspect us of walking being ready to punish every disobedience, according to the flesh. 3 For though we when your obedience is complete. beyond what is necessary—only inasmuch Context as it pushes them towards holiness and love for each other. • 10:1 When Paul speaks of the meekness and gentleness of Christ, he is pointing to • 10:3 Paul does a little wordplay here— the way in which Christ walked humbly he is apparently being accused by false before men with kindness and compassion teachers in Corinth of “walking in the despite his incredible power and wisdom. flesh” or living by his worldly lusts and Meekness is not weakness, but rather passions. He takes this accusation and power under control. -

The Cross and Christian Generosity 2 Corinthians 8-9 Where We're Going

The Cross and Christian Community The Cross and Christian Generosity Dr. David Platt November 24, 2013 The Cross and Christian Generosity 2 Corinthians 8-9 If you have His Word, and I hope you do, I’m going to invite you to open with me to 2 Corinthians 8. Pull out that Worship Guide you received when you came in. I know growing up as a kid—in my house and now as a husband and a dad in my house—there were times when my dad or now I (as dad) would call a family meeting, and everybody gets together around the room, and you know there’s maybe something to celebrate or maybe there’s something in the family that we need to address. As I have prayed about and prepared this week in light of this text for this gathering right now, I feel like that’s what this is. In a way, it’s different. There’s a sense in which this happens every week when we gather together as a faith family to meet together. So, in a sense, every Sunday is that, but maybe in a unique way today, in light of some things that are particularly heavy on my heart as a pastor in this faith family, I put aside my notes and iPad that I usually use and got the Worship Guide here that’s got some notes in it. I was not going to have anything; I was just going to stand or sit on the stairs or something, but my back’s been causing some problems, so I’m going to have something to lean on. -

2 Corinthians 2:14-4:18 the Glory of Christian Ministry

Grace Theological Journal 2.2 (Fall 1981) 171-89 Copyright © 1981 by Grace Theological Seminary. Cited with permission. THE GLORY OF CHRISTIAN MINISTRY AN ANAYSIS OF 2 CORINTHIANS 2:14-4:18 HOMER A. KENT, JR. Some activities have a special appeal about them. People are drawn to certain pursuits because of the excitement generated by the activ- ity itself. Others are attracted by the financial rewards, by the adulation of an audience, or by the popular esteem in which some activities are held. The sense of satisfaction and fulfillment afforded by such occupations as medicine, education, and social work can lead to an entire career. The Christian ministry was once one of those highly respected vocations. Shifting attitudes in recent years, however, have caused changes in society's values. Our "scientific" age tends to place on the pedestal of public esteem the research scientist, the surgeon, and the sports hero. Yet the reasons why the Christian minister once headed the list of respected leaders in American life are still valid and worthy of serious reflection. The apostle Paul wrote in this passage about the activity that had captivated him. He was not attracted by any financial rewards, for it offered none to him. He gained from it no earthly pomp, no public prestige (except the respect of the Christians he had helped, and even this was mixed). He experienced abandonment and hatred that would demoralize most men. Nevertheless he was so enthralled with the privilege of Christian ministry that he made it his career and never found anything that could entice him away from this glorious passion of his life. -

2 Corinthians

Vol. 19 • Num. 3 Fall 2015 2 Corinthians Stephen J. Wellum 5 Editorial: Learning from Paul’s Second Letter to Corinth Mark Seifrid 9 The Message of Second Corinthians: 2 Corinthians as the Legitimation of the Apostle Matthew Y. Emerson and Christopher W. Morgan 21 The Glory of God in 2 Corinthians George H. Guthrie 41 Καταργέω and the People of the Shining Face (2 Corinthians 3:7-18) Matthew Barrett 61 What is So New About the New Covenant? Exploring the Contours of Paul’s New Covenant Theology in 2 Corinthians 3 Joshua M. Greever 97 “We are the Temple of the Living God” (2 Corinthians 6:14- 7:1): The New Covenant as the Fulfillment of God’s Promise of Presence Thomas R. Schreiner 121 Sermon: A Building from God—2 Corinthians 5:1-10 Book Reviews 131 Editor-in-Chief: R. Albert Mohler, Jr. • Editor: Stephen J. Wellum • Associate Editor: Brian Vickers • Book Review Editor: Jarvis J. Williams • Assistant Editor: Brent E. Parker • Editorial Board: Randy L. Stinson, Daniel S. Dumas, Gregory A. Wills, Adam W. Greenway, Dan DeWitt, Timothy Paul Jones, Jeff K. Walters, Steve Watters, James A. Smith, Sr. Typographer:• Gabriel Reyes-Ordeix • Editorial Office: SBTS Box 832, 2825 Lexington Rd., Louisville, KY 40280, (800) 626-5525, x 4413 • Editorial E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Editorial: Learning from Paul’s Second Letter to Corinth Stephen J. Wellum Stephen J. Wellum is Professor of Christian Theology at The Southern Baptist Theolog- ical Seminary and editor of Southern Baptist Journal of Theology. He received his Ph.D. -

2 Cor Session 1

This morning we will continue our series on Paul’s early letters. Paul’s early letters all focused on establishing his young churches in the gospel. Last week we finished 1 Corinthians and this morning we turn our attention to 2 Corinthians. 2 Corinthians is a very different type of letter since it is not primarily bringing focusing on the kerygma and didache, but rather on Paul’s relationship with the Corinthians. Why would he devote a large letter to his relationship with the Corinthians? Paul’s Early Epistles 8You see, my dear family, we don’t want to keep you in the dark about the suffering we went through in Asia. The load we had to carry was far too heavy for us; it got to the point where we gave up on life itself. 2 Corinthians 1:8 N. T. Wright 4No: I wrote to you in floods of tears, out of great trouble and anguish in my heart, not so that I could make you sad but so that you would know just how much overflowing love I have toward you. 2 Corinthians 2:4 N. T. Wright Paul’s Early Epistles 12 However, when I came to Troas to announce the Messiah’s gospel, and found an open door waiting for me in the Lord, 13 I couldn’t get any quietness in my spirit because I didn’t find my brother Titus there. So I left them and went off to Macedonia. 2 Corinthians 2:12–13 N. T. Wright 3 So: we’re starting to “recommend ourselves” again, are we? Or perhaps we need—as some do—official references to give to you? Or perhaps even to get from you? 2 Corinthians 3:3 N. -

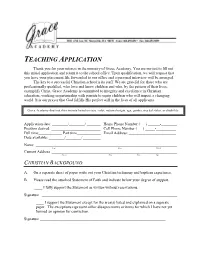

2019 Teaching Application

TEACHING APPLICATION Thank you for your interest in the ministry of Grace Academy. You are invited to fill out this initial application and return it to the school office. Upon qualification, we will request that you have your placement file forwarded to our office and a personal interview will be arranged. The key to a successful Christian school is its staff. We are grateful for those who are professionally qualified, who love and know children and who, by the pattern of their lives, exemplify Christ. Grace Academy is committed to integrity and excellence in Christian education; working in partnership with parents to equip children who will impact a changing world. It is our prayer that God fulfills His perfect will in the lives of all applicants. Grace Academy does not discriminate based on race, color, national origin, age, gender, marital status, or disability. Application date: ________/________/ _______ Home Phone Number ( ) ______-________ Position desired: _________________________ Cell Phone Number ( ) _____-__________ Full time____________ Part time____________ Email Address: ________________________ Date available: ________/________/ _________ Name ________________________________________________________________________ Last First Middle Current Address ________________________________ ________________________________ Street City State Zip CHRISTIAN BACKGROUND A. On a separate sheet of paper write out your Christian testimony and baptism experience. B. Please read the attached Statement of Faith and indicate below your degree of support. ____ I fully support the Statement as written without reservations. Signature _____________________________________________________________________ ____ I support the Statement except for the area(s) listed and explained on a separate paper. The exceptions represent either disagreements or items for which I have not yet formed an opinion for conviction. -

Doctrine and Beliefs: Trinity: God Eternally Exists As Three Persons

Doctrine and Beliefs: Trinity: God eternally exists as three persons: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. The three distinct persons of the Trinity are all fully God; all of God’s attributes are true of each person and together they are one God. While the word “trinity” never appears in Scripture, it is an accepted doctrine based on the Bible’s teachings as a whole. We see throughout Scripture, evidence of the Trinity (Matthew 3:16-17, Matthew 28:19, John 1:1-5, John 13:20, 1 Corinthians 12:4-6, 2 Corinthians 13:14, Ephesians 2:18, 1 Peter 1:2). Additional Supportive Scripture: John 1:14, John 10:30, John 14 16-17, John 14:26, John 15:26, 1 Corinthians 8:6, Ephesians 4:4-6, Philippians 2:5-8, Colossians 1:15-17, Colossians 2:9-10, 1 John 5:7-8 God the Father: The first member of the Trinity is God the Father. He is the Creator and Sustainer of all things (Genesis 1:1, Colossians 1:16, Acts 4:24, Hebrews 1:3, Revelation 4:11). God is sovereign and infinite, meaning He has no limitations. God the Father can be intimately known but because of His infiniteness, He can never be fully known (Psalm 145:3, Jeremiah 9:23-24, Romans 11:33). God the Father can only be known through Jesus (Matthew 11:27, John 14:6). Jesus Christ: Jesus is the second member of the Trinity and the Son of God. He is God incarnate as man, and He is both fully God and fully human (Luke 24:39, John 1:1, John 1:18, Romans 9:5, Colossians 1:19, Colossians 2:9). -

PRACTICING GENEROSITY 2 Corinthians 8:10-24 Jeffrey S. Carlson (With Material Inspired by the Grace of Giving by John Stott) November 10, 2019

THE GENEROSITY OF GIVING (2) PRACTICING GENEROSITY 2 Corinthians 8:10-24 Jeffrey S. Carlson (With material inspired by The Grace of Giving by John Stott) November 10, 2019 INTRODUCTION Today marks the second in a three-part series exploring Paul’s teaching on Christian giving as found in 2 Corinthians 8 & 9. In these chapters Paul is explaining arrangements for an offering from the Greek churches in Macedonia and Achaia to help the struggling churches in Judea. For Paul, not all giving is helpful. So he provides guidelines to make sure that it is helpful. To put it another way, the practice of generosity needs to answer three questions in the affirmative based on three different passages in chapter 8. SCRIPTURE And in this matter I am giving my advice: it is appropriate for you who began last year not only to do something but even to desire to do something— 11now finish doing it, so that your eagerness may be matched by completing it according to your means. 12For if the eagerness is there, the gift is acceptable according to what one has—not according to what one does not have (2 Corinthians 8:10-12 NRSV). 1. IS THE GIVING PROPORTIONATE? In order to practice helpful generosity we need to ask, “Is our giving proportionate?” During the previous year the Corinthian Christians had been the first to say that they would be willing to give to the cause of helping the Judean Christians. So now Paul urges them to complete what they had begun by matching their words with their actions. -

2 Corinthians 12:9 Commentary

2 Corinthians 12:9 Commentary PREVIOUS NEXT 2 CORINTHIANS - PAUL'S MINISTRY IN THE LIGHT OF THE INDESCRIBABLE GIFT Click chart to enlarge Charts from Jensen's Survey of the NT - used by permission Another Chart from Charles Swindoll A Third Chart Overview of Second Corinthians 2Co 1:1-7:16 2Co 8:1-9:15 2Co 10:1-12:21 Character Collection Credentials of Paul for the Saints of Paul Testimonial & Didactic Practical Apologetic Past: Present: Future: Misunderstanding & Explanation Practical Project Anxieties Apostle's Solicitation for Judean Apostle's Vindication Apostle's Conciliation, Ministry & Exhortations Saints of Himself Forgiveness, Reconciliation Confidence Vindication Gratitude Ephesus to Macedonia: To Corinth: Macedonia: Preparation for Change of Itinerary Certainty and Imminence Visit to Corinth Explained of the Visit 2Co 1:1-7:16 2Co 8:1-9:15 2Co 10:1-12:21 2Corinthians written ~ 56-57AD - see Chronological Table of Paul's Life and Ministry Adapted & modified from Jensen's Survey of the New Testament (Highly Recommended Resource) & Wilkinson's Talk Thru the Bible INTRODUCTIONS TO SECOND CORINTHIANS: IRVING JENSEN - Introduction and study tips - excellent preliminary resource - scroll to page 1877 (Notes on both 1-2 Cor begin on p 1829) JOHN MACARTHUR 2 Corinthians Introduction - same as in the Study Bible JAMES VAN DINE 2 Corinthians - Author, Purpose, Outline, Argument CHARLES SWINDOLL - 2 Corinthians Overview MARK SEIFRID - The Message of Second Corinthians: 2 Corinthians as the Legitimation of the Apostle J VERNON MCGEE - 2 Corinthians Introduction DAN WALLACE - 2 Corinthians: Introduction, Argument, and Outline DAVID MALICK - An Introduction To Second Corinthians 2 Corinthians 12:9 And He has said to me, "My grace is sufficient for you, for My power is perfected in weakness. -

2 Corinthians 11:30–31 (NKJV) 30 If I Must Boast, I Will Boast in the Things Which Concern My Infirmity

(2 Corinthians 11:16-33) 2 Corinthians 11:30–31 (NKJV) 30 If I must boast, I will boast in the things which concern my infirmity. 31 The God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who is blessed forever, knows that I am not lying. Paul’s Reluctant Boasting / His Suffering For Christ 30 If I must boast, I will boast in the things which concern my infirmity. 31 The God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who is blessed forever, knows that I am not lying. Defense of Paul’s apostolic authority — 10:1-13:10 Concern for their faithfulness - 11:1-4 Equal to the others — 11:5,6 Paul’s free gift to them — 11:7-11 Warns of false teachers — 11:12-15 Reluctant boasting in his sufferings — 11:16-31 2 Corinthians 11:16–33 (NKJV) 16 I say again, let no one think me a fool. If otherwise, at least receive me as a fool, that I also may boast a little. 17 What I speak, I speak not according to the Lord, but as it were, foolishly, in this confidence of boasting. 18 Seeing that many boast according to the flesh, I also will boast. 19 For you put up with fools gladly, since you yourselves are wise! 2 Corinthians 11:16–33 (NKJV) 20 For you put up with it if one brings you into bondage, if one devours you, if one takes from you, if one exalts himself, if one strikes you on the face. 21 To our shame I say that we were too weak for that! But in whatever anyone is bold—I speak foolishly—I am bold also. -

Endurance Is Possible 2 Corinthians 4:7-12 Power; Gospel

Endurance Is Possible 2 Corinthians 4:7-12 Power; Gospel; Perseverance; Trial; Persecution; Adversity; Affliction; Death; Life 4/19/20; Grace Church of Lockeford; 504 Introduction “No Christian should ever complain to God because of his lack of gifts or abilities, or because of his limitations or handicaps. Psalm 139:13–16 indicates that our very genetic structure is in the hands of God. Each of us must accept himself and be himself.”1 1. The Power Of Jesus v. 7 a. The demand for His power v. 7a “‘Earthen’ or ‘clay’ jars, as opposed to bronze ones, were readily discarded; because clay was always available, such containers were cheap and disposable if they were broken or incurred ceremonial impurity—an odd container for a rich treasure.”2 “Such vessels were regarded as fragile and as expendable because they were cheap and often unattractive.”3 “We are but earthen jars used of God for his purposes (Rom. 9:20ff.) and so fragile.”4 “The idea of light in earthen vessels is, however, best illustrated in the story of the lamps and pitchers of Gideon, Judges 7:16. In the very breaking of the vessel the light is revealed.”5 “Even though it is what dispels spiritual darkness God has deposited this precious gift in every clay Christian.”6 “It is precisely the Christian’s utter frailty which lays him open to the experience of the all- sufficiency of God’s grace, so that he is able even to rejoice because of his weakness (12:9f.)— something that astonishes and baffles the world, which thinks only in terms of human ability.”7 “That Paul is an “earthen vessel” in the first instance signifies his intrinsic lack of worth; earthenware pots were inexpensive, common, and impermanent.