Translating Communism for Children: Fables and Posters of the Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Commedia Dell’Arte: History, Myth, Reception Daniele Vianello

Introduction Commedia dell’Arte: History, Myth, Reception Daniele Vianello Today, the commedia dell’arte is widely regarded as one of the most significant phenomena in the history of European theatre. Its famous stock characters, which have become an integral part of the collective imagin- ation, are widely accepted as the very emblem of theatre. From the second half of the twentieth century onwards, the commedia dell’arte has been the subject of substantial research, mostly by Italian scholars, who have re-evaluated its characteristic features and constitutive elements. These studies remain largely untranslated in English. Further- more, there are no publications which provide a comprehensive overview of this complex phenomenon or which reconstruct not only its history but also its fortunes over time and space. An historical overview was published by Kenneth and Laura Richards in , but this is now considered dated. More recent studies are limited to the discussion of specific issues or to particular geographical areas or periods of time. For example, Robert Henke (), Anne MacNeil () and M. A. Katritzky () analyse individual aspects between the late Renaissance and the early seventeenth century. The Routledge Companion to Commedia dell’Arte (Chaffee and Crick ) has the practitioner rather than the scholar in focus. In Italy, Roberto Tessari () and Siro Ferrone (), in their important recent contributions focus almost exclusively on the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The main purpose of this book is to retrace the history of the improvvisa in light of its legendary past, with special focus on the theatrical practices and theoretical deliberations in the century which has just ended. -

The Performative Nature of Dramatic Imagination

PERFORMANCE PHILOSOPHY E-ISSN 2237-2660 The Performative Nature of Dramatic Imagination Rubén Vega BalbásI IUniversidad Nebrija – Madrid, Spain ABSTRACT – The Performative Nature of Dramatic Imagination – Creative imagination is a central concept in critical philosophy which establishes the framing faculty of the subject in the middle of the cognitive process. Linking the internal and the external, imagination is also key for dramatic acting methodologies. This mediation has been alternatively interpreted in Western tradition under a reversible perspective, giving priority to either the process that goes from the outside inwards (aesthesis) or just the opposite (poiesis). Going beyond dialectics, this article will connect philosophy with dramatic theory. My proposal explores the virtual drama of identity to emphasise how the transcendental and empirical get linked theatrically. Keywords: Imagination. Drama. Performance. Acting. Performance Philosophy. RÉSUMÉ – La Nature Performatif de l’Imagination Créatice – L’imagination créatrice est un concept central de la philosophie critique qui établit la faculté de cadrage du sujet, dans la mesure où elle joue le rôle de médiateur entre le monde mental et le monde matériel, au milieu du processus cognitif. Liant l’imaginaire à l’externe, l’imagination est également essentielle pour les méthodologies du jeu dramatique. Cette médiation a été interprétée alternativement dans la tradition occidentale selon une perspective réversible, en donnant la priorité soit au processus allant de l’extérieur vers l’intérieur (aesthesis), soit au contraire (la poiesis). Au-delà de la dialectique, cet article associera la philosophie à la théorie dramatique. Ma thèse explore le drame virtuel de l’identité et, si l’imagination et les actes performatifs dépendent les uns des autres en tant que poursuites humaines, avec le terme dramatisation je souligne comment le transcendantal et l’empirique sont liés théâtralement. -

„Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 142 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Halina Stephan „Lef“ and the Left Front of the Arts Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access S la v istich e B eiträge BEGRÜNDET VON ALOIS SCHMAUS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON JOHANNES HOLTHUSEN • HEINRICH KUNSTMANN PETER REHDER JOSEF SCHRENK REDAKTION PETER REHDER Band 142 VERLAG OTTO SAGNER MÜNCHEN Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 HALINA STEPHAN LEF” AND THE LEFT FRONT OF THE ARTS״ « VERLAG OTTO SAGNER ■ MÜNCHEN 1981 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München ISBN 3-87690-186-3 Copyright by Verlag Otto Sagner, München 1981 Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner, München Druck: Alexander Grossmann Fäustlestr. 1, D -8000 München 2 Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 To Axel Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access Halina Stephan - 9783954792801 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 05:25:44AM via free access 00060802 CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................ -

The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater By

Directed Culture: The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater By Howard Douglas Allen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria E. Bonnell, Chair Professor Ann Swidler Professor Yuri Slezkine Fall 2013 Abstract Directed Culture: The Spectator and Dialogues of Power in Early Soviet Theater by Howard Douglas Allen Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria E. Bonnell, Chair The theater played an essential role in the making of the Soviet system. Its sociological interest not only lies in how it reflected contemporary society and politics: the theater was an integral part of society and politics. As a preeminent institution in the social and cultural life of Moscow, the theater was central to transforming public consciousness from the time of 1905 Revolution. The analysis of a selected set of theatrical premieres from the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917 to the end of Cultural Revolution in 1932 examines the values, beliefs, and attitudes that defined Soviet culture and the revolutionary ethos. The stage contributed to creating, reproducing, and transforming the institutions of Soviet power by bearing on contemporary experience. The power of the dramatic theater issued from artistic conventions, the emotional impact of theatrical productions, and the extensive intertextuality between theatrical performances, the press, propaganda, politics, and social life. Reception studies of the theatrical premieres address the complex issue of the spectator’s experience of meaning—and his role in the construction of meaning. -

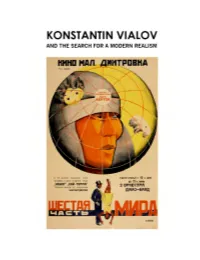

Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph

Aleksandr Deineka, Portrait of the artist K.A. Vialov, 1942. Oil on canvas. National Museum “Kyiv Art Gallery,” Kyiv, Ukraine Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. D. Edited by Brian Droitcour Design and production by Jolie Simpson Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Research Assistant: Elena Emelyanova, Research Curator, Rare Books Department, Russian State Library, Moscow Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2018 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2018 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Poster for Dziga Vertov’s Film Shestaia chast’ mira (A Sixth Part of the World), 1926. Lithograph, 42 1/2 x 28 1/4” (107.9 x 71.7 cm) Plate XVII Note on transliteration: For this catalogue we have generally adopted the system of transliteration employed by the Library of Congress. However, for the names of artists, we have combined two methods. For their names according to the Library of Congress system even when more conventional English versions exist: e.g. , Aleksandr Rodchenko, not Alexander Rodchenko; Aleksandr Deineka, not Alexander Deineka; Vasilii Kandinsky, not Wassily Kandinsky. Surnames with an “-ii” ending are rendered with an ending of “-y.” But in the case of artists who emigrated to the West, we have used the spelling that the artist adopted or that has gained common usage. Soft signs are not used in artists’ names but are retained elsewhere. TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 - ‘A Glimpse of Tomorrow’: Konstantin Vialov and the Search for a Modern Realism” by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph. -

Deep Time of the Media ELECTRONIC CULTURE: HISTORY, THEORY, and PRACTICE

Deep Time of the Media ELECTRONIC CULTURE: HISTORY, THEORY, AND PRACTICE Ars Electronica: Facing the Future: A Survey of Two Decades edited by Timothy Druckrey net_condition: art and global media edited by Peter Weibel and Timothy Druckrey Dark Fiber: Tracking Critical Internet Culture by Geert Lovink Future Cinema: The Cinematic Imaginary after Film edited by Jeffrey Shaw and Peter Weibel Stelarc: The Monograph edited by Marquard Smith Deep Time of the Media: Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means by Siegfried Zielinski Deep Time of the Media Toward an Archaeology of Hearing and Seeing by Technical Means Siegfried Zielinski translated by Gloria Custance The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2006 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Originally published as Archäologie der Medien: Zur Tiefenzeit des technischen Hörens und Sehens, © Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, 2002 The publication of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any elec- tronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. I have made every effort to provide proper credits and trace the copyright holders of images and texts included in this work, but if I have inadvertently overlooked any, I would be happy to make the necessary adjustments at the first opportunity.—The author MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. -

Evreinov and Questions of Theatricality

Evreinov and Questions of Theatricality Inga Romantsova BA (Theatre and Film) St Petersburg State Theatre Arts Academy; MA (Theatre and Film) University of New South Wales A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in Drama November 2017 This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship I hereby certify that the work embodied in the thesis is my own work, conducted under normal supervision. The thesis contains no material which has been accepted, or is being examined, for the award of any other degree or diploma in any other university or other tertiary institute and to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to the final version of my thesis being made available worldwide when deposited in the University’s Digital Repository, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 and any approved embargo. Inga Romantsova Declaration of Transliteration I, Inga Romantsova, Australian citizen born in Voronezh, Russia, hereby declare that I am fluent in both the English and Russian languages and the translations and transliterations provided in this dissertation are true and accurate. The transcriptions from Russian (Cyrillic) into English are based on the 'Modified Library of Congress' system, widely used by all major libraries in the UK and the USA. Abstract As a professional actor I have always been puzzled by the question of what drives our desire for acting. Russian theatre practitioner of the 20th Century Nikolai Evreinov preconceived or intuitively searched for an answer to that exact same question, and he believed he found it. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents • Abbreviations & General Notes 2 - 3 • Photographs: Flat Box Index 4 • Flat Box 1- 43 5 - 61 Description of Content • Lever Arch Files Index 62 • Lever Arch File 1- 16 63 - 100 Description of Content • Slide Box 1- 7 101 - 117 Description of Content • Photographs in Index Box 1 - 6 118 - 122 • Index Box Description of Content • Framed Photographs 123 - 124 Description of Content • Other 125 Description of Content • Publications and Articles Box 126 Description of Content Second Accession – June 2008 (additional Catherine Cooke visual material found in UL) • Flat Box 44-56 129-136 Description of Content • Postcard Box 1-6 137-156 Description of Content • Unboxed Items 158 Description of Material Abbreviations & General Notes, 2 Abbreviations & General Notes People MG = MOISEI GINZBURG NAM = MILIUTIN AMR = RODCHENKO FS = FEDOR SHEKHTEL’ AVS = SHCHUSEV VNS = SEMIONOV VET = TATLIN GWC = Gillian Wise CIOBOTARU PE= Peter EISENMANN WW= WALCOT Publications • CA- Современная Архитектура, Sovremennaia Arkhitektura • Kom.Delo – Коммунальное Дело, Kommunal’noe Delo • Tekh. Stroi. Prom- Техника Строительство и Промышленность, Tekhnika Stroitel’stvo i Promyshlennost’ • KomKh- Коммунальное Хозяство, Kommunal’noe Khoziastvo • VKKh- • StrP- Строительная Промышленность, Stroitel’naia Promyshlennost’ • StrM- Строительство Москвы, Stroitel’stvo Moskvy • AJ- The Architect’s Journal • СоРеГор- За Социалистическую Реконструкцию Городов, SoReGor • PSG- Планировка и строительство городов • BD- Building Design • Khan-Mag book- Khan-Magomedov’s -

Theatrical Spectatorship in the United States and Soviet Union, 1921-1936: a Cognitive Approach to Comedy, Identity, and Nation

Theatrical Spectatorship in the United States and Soviet Union, 1921-1936: A Cognitive Approach to Comedy, Identity, and Nation Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Pamela Decker, MA Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Advisor Jennifer Schlueter Frederick Luis Aldama Copyright by Pamela Decker 2013 Abstract Comedy is uniquely suited to reveal a specific culture’s values and identities; we understand who we are by what and whom we laugh at. This dissertation explores how comic spectatorship reflects modern national identity in four theatre productions from the twentieth century’s two rising superpowers: from the Soviet Union, Evgeny Vakhtangov’s production of Princess Turandot (1922) and Vsevolod Meyerhold’s production of The Bedbug (1929); from the United States, Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle’s Broadway production of Shuffle Along (1921) and Orson Welles’ Federal Theatre Project production of Horse Eats Hat (1936). I undertake a historical and cognitive analysis of each production, revealing that spectatorship plays a participatory role in the creation of live theatre, which in turn illuminates moments of emergent national identities. By investigating these productions for their impact on spectatorship rather than the literary merit of the dramatic text, I examine what the spectator’s role in theatre can reveal about the construction of national identity, and what cognitive studies can tell us about the spectator’s participation in live theatre performance. Theatre scholarship often marginalizes the contribution of the spectator; this dissertation privileges the body as the first filter of meaning and offers new insights into how spectators contribute and shape live theatre, as opposed to being passive observers of an ii already-completed production. -

Soviet Montage Cinema As Propaganda and Political Rhetoric

Soviet Montage Cinema as Propaganda and Political Rhetoric Michael Russell Doctor of Philosophy The University of Edinburgh 2009 This thesis is dedicated to the memory of Professor Dietrich Scheunemann. ii Propaganda that stimulates thinking, in no matter what field, is useful to the cause of the oppressed. Bertolt Brecht, 1935. iii Abstract Most previous studies of Soviet montage cinema have concentrated on its aesthetic and technical aspects; however, montage cinema was essentially a rhetoric rather than an aesthetic of cinema. This thesis presents a com- parative study of the leading montage film-makers – Kuleshov, Pudovkin, Eisenstein and Vertov – comparing and contrasting the differing methods by which they used cinema to exert a rhetorical effect on the spectator for the purposes of political propaganda. The definitions of propaganda in general use in the study of Soviet montage cinema are too narrowly restrictive and a more nuanced definition is clearly needed. Furthermore, the role of the spectator in constituting the rhetorical effectivity of a montage film has been neglected; a psychoanalytic model of the way in which the filmic text can trigger a change in the spectator’s psyche is required. Moreover, the ideology of the Soviet montage films is generally assumed to exist only in their content, whereas in classical cinema ideology also operates at the level of the enunciation of the filmic text itself. The extent to which this is also true for Soviet montage cinema should be investigated. I have analysed the interaction between montage films and their specta- tors from multiple perspectives, using several distinct but complementary theoretical approaches, including recent theories of propaganda, a psycho- analytic model of rhetoric, Lacanian psychoanalysis and the theory of the system of the suture, and Peircean semiotics. -

Of Theatre. 71

“The Theatrical Pendulum: Paths of Innovation in the Modernist Stage” by Andrés Pérez-Simón A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto © Copyright by Andrés Pérez-Simón, 2010 “The Theatrical Pendulum: Paths of Innovation in the Modernist Stage” Andrés Pérez-Simón Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Comparative Literature University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This dissertation examines the renovation of the modernist stage, from the beginning of the twentieth century to the late 1930s, via a retrieval of three artistic forms that had marginal importance in the commercial theatre of the nineteenth century. These three paths are the commedia dell’arte, puppetry and marionettes, and, finally, what I denominate mysterium, following Elinor Fuch’s terminology in The Death of Character. This dissertation covers the temporal span of the first three decades of the twentieth century and, at the same time, analyzes modernist theatre in connection with the history of Western drama since the consolidation of the bourgeois institution of theatre around the late eighteenth century. The Theatrical Pendulum: Paths of Innovation in the Modernist Staget studies the renovation of the bourgeois institution of theatre by means of the rediscovery of artistic forms previously relegated to a peripheral status in the capitalist system of artistic production and distribution. In their dramatic works, Nikolai Evreinov, Josef and Karel Čapek, Massimo Bontempelli, and Federico García Lorca present fictional actors, playwrights and directors who resist the fact that their work be evaluated as just another commodity. These dramatists collaborate with the commercial stage of their time, ii instead of adopting the radical stance that characterized avant-garde movements such as Italian futurism and Dadaism. -

The Role of Socialist Competition in Establishing Labour Discipline in the Soviet Working Class, 1928-1934 Part 2

University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. 2nd of 2 files Part Two: Chapters 5 to 7 Appendices and Bibliography THE ROLE OF SOCIALIST COMPETITION IN ESTABLISHING LABOUR DISCIPLINE IN THE SOVIET WORKING CLASS, 1928-1934 By John Russell Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Russian and East European Studies Commerce & Social Science Division University of Birmingham 1987 PART TWO -151- SOCIALIST COMPETITION Introduction Among the most striking features of the Soviet industrialisation drive during the period under review that distinguish it from corresponding developments in other countries was the role accorded to socialist competition. The importance attached to this phenomenon by the Party leadership and the speed with which it spread through Soviet society are attested to by the fact that at the beginning of 1929 the term 'socialist competition' (sotsialisticheskoe sorevnovanie) had yet to be coined, whereas by the end of that year it had already become an integral and, as it transpired, permanent feature of Soviet industrial relations. This Chapter examines the origins, aims development and characteristics of socialist competition with special reference to its role in the establishment of labour discipline.