A Review of Eight University Clarinet Studios: an Investigation of Pedagogical Style, Content and Philosophy Through Observation and Interviews Margaret Iris Dees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

David Dzubay

all water has a perfect memory DAVID DZUBAY david Dzubay Disc A 69:46 Disc B 58:29 String Quartet No. 1 “Astral” 1. Double Black Diamond 10:08 common sense COMPOSERS’ COLLECTIVE SPARK 1. Voyage 5:57 Indiana University New Music Ensemble; 2. Starry Night 4:07 David Dzubay, conductor 3. S.E.T.I. 1:50 4. Wintu Dream Song 6:23 Kukulkan II 5. Supernova 3:39 2. Kukulkan’s Ascent (El Castillo March equinox) 2:37 all water has a perfect memory Orion String Quartet 3. Water Run (Profane Well) 3:31 6. all water has a perfect memory 15:12 4. Celestial Determination (El Caracol) 1:56 Voices of Change 5. Processional-Offering (Sacred Well) 4:51 6. Quetzalcoatl’s Sacrifice (The Great Ball Court) 4:13 7. Producing For A While 8:21 7. Kukulkan’s Descent (El Castillo September equinox) 2:13 Voices of Change Indiana University New Music Ensemble 8. Delicious Silence 7:11 Chamber Concerto for Trumpet, Violin & Ensemble Miranda Cuckson, violin 8. Déjà vu (passacaglia sospeso) 13:20 9. Rapprochement (intermezzo) 9:08 9. Lament 9:28 10. Détente(s) (scherzo) 6:31 Barkada Quartet Indiana University New Music Ensemble; 10. Volando 4:27 David Dzubay, conductor Zephyr Simin Ganatra, violin John Rommel, trumpet/flugelhorn/piccolo trumpet 11. Lullaby 3:09 Emily Levin, harp innova 011 © David Dzubay. All Rights Reserved, 2019. innova 024 innova® Recordings is the label of the American Composers Forum. innova.mu pronovamusic.com all water has a perfect memory solo, chamber and ensemble music by David Dzubay Welcome to this survey of some of my music from the narrative-based music remains somewhat abstract and early 21st century! The first disc assembles performanc- personal; the composer and audience may have very es from a variety of chamber ensembles and soloists, different interpretations of the same music because so spanning a period from 2003-2015. -

Orfeo Euridice

ORFEO EURIDICE NOVEMBER 14,17,20,22(M), 2OO9 Opera Guide - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS What to Expect at the Opera ..............................................................................................................3 Cast of Characters / Synopsis ..............................................................................................................4 Meet the Composer .............................................................................................................................6 Gluck’s Opera Reform ..........................................................................................................................7 Meet the Conductor .............................................................................................................................9 Meet the Director .................................................................................................................................9 Meet the Cast .......................................................................................................................................10 The Myth of Orpheus and Eurydice ....................................................................................................12 OPERA: Then and Now ........................................................................................................................13 Operatic Voices .....................................................................................................................................17 Suggested Classroom Activities -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

JEAN ANN HITE Résumé, April 2012 440 W. 21St Street, Box 211 New

JEAN ANN HITE Résumé, April 2012 440 W. 21st Street, Box 211 New York, NY 10011 Cell Phone: (239) 980-0912 Email: [email protected] Objective: To obtain a position as a rector or an assistant/associate rector or curate, focusing on reconciliation, teaching and preaching, liturgy and worship, formation and pastoral care Present Status: Transitional Deacon, Episcopal Diocese of SW Florida • Student, The General Theological Seminary (New York City), Class of 2012, Master of Divinity degree program Work Experience: 2011-Present St. Clement’s Episcopal Church, New York, NY: Seminarian Intern • Preaching • Liturgical Diaconal Ministry • Spiritual director 2010–Present The Church of the Epiphany, New York, NY: Seminarian Intern • Adult Education: Class content design and facilitation • Quiet Day Meditations • Liturgical Diaconal Ministry and Evening Prayer Officiant • Preaching • Office and web-site consultation Summer 2011 St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Marco Island, FL: Seminarian Intern • Camp Able (summer camp for disabled children) • Vacation Bible School • Preaching • Pastoral care seminars Summer 2010 Morton Plant Hospital, Clearwater, FL: Clinical Pastoral Education • Hospital Chaplain 2006-2009 St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, Bonita Springs, FL: Lay Leadership • Establishment and leadership of Taizé worship • Morning and Evening Prayer Officiant; Lay Reader and Leader • Preaching (weekend Eucharists, Taizé, weekday Eucharists) • Pastoral care representation - Bentley Village, Naples • Nursing home ministry • Lay Eucharistic and Visitation -

The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration Into the Modern Clarinet Studio

UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones 5-1-2015 The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio Jennifer Beth Iles University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Music Commons, and the Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Iles, Jennifer Beth, "The hC anging Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio" (2015). UNLV Theses/Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones. Paper 2367. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Scholarship@UNLV. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses/ Dissertations/Professional Papers/Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE BASS CLARINET: SUPPORT FOR ITS INTEGRATION INTO THE MODERN CLARINET STUDIO By Jennifer Beth Iles Bachelor of Music Education McNeese State University 2005 Master of Music Performance University of North Texas 2008 A doctoral document submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada Las Vegas May 2015 We recommend the dissertation prepared under our supervision by Jennifer Iles entitled The Changing Role of the Bass Clarinet: Support for Its Integration into the Modern Clarinet Studio is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Department of Music Marina Sturm, D.M.A., Committee Chair Cheryl Taranto, Ph.D., Committee Member Stephen Caplan, D.M.A., Committee Member Ken Hanlon, D.M.A., Committee Chair Margot Mink Colbert, B.S., Graduate College Representative Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D., Interim Dean of the Graduate College May 2015 ii ABSTRACT The bass clarinet of the twenty-first century has come into its own. -

Teaching the Three T's of Clarinet Playing: Tone, Technique and Tonguing Dr

Teaching The Three T's of Clarinet Playing: Tone, Technique and Tonguing Dr. Gail Lehto Zugger OMEA Professional Development Conference February 1, 2019 This clinic will provide practical tips to improve your clarinet students, focusing on visual and aural cues to diagnose common problems. Basic fundamentals of technique, tone production and articulation will be discussed, giving effective strategies to teach these concepts to beginning, intermediate and advanced clarinetists. Simple exercises to develop good hand and finger position and improve transitions between registers will be demonstrated. Effective equipment options will be included. I. Assembly, Posture and Hold Position: A. Press D key on upper stack while gently twisting together with lower stack so as to not bend the bridge mechanism. B. When adding bell to the lower stack, grip the lower stack where there are no keys, on the bore only. Don’t bend the long metal rods associated with the pinky keys. C. Use cork grease regularly to reduce bending/breaking mechanisms. D. Place ligature on mouthpiece first, then insert reed from above so reed is less likely to become chipped during assembly. Just a shadow of the mouthpiece should be visible at the tip behind the reed. E. Head and neck should be in a natural-looking position while sitting tall. “Bring the instrument to you, not you to the instrument.” F. Clarinet angle to the body of 30-35 degrees. Right elbow should not rest on right thigh. Clarinet neck straps can relieve some weight off the right wrist. II. Tone A. Air—volume, air speed and support all keys to success. -

The Concerto for Bassoon by Andrzej Panufnik

THE CONCERTO FOR BASSOON BY ANDRZEJ PANUFNIK: RELIGION, LIBERATION AND POSTMODERNISM Janelle Ott Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2016 APPROVED: Kathleen Reynolds, Major Professor Eugene Cho, Committee Member John Scott, Committee Member James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Ott, Janelle. The Concerto for Bassoon by Andrzej Panufnik: Religion, Liberation, and Postmodernism. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2016, 128 pp., 2 charts, 23 musical examples, references, 88 titles. The Concerto for Bassoon by Andrzej Panufnik is a valuable addition to bassoon literature. It provides a rare opportunity for the bassoon soloist to perform a piece which is strongly programmatic. The purpose of this document is to examine the historical and theoretical context of the Concerto for Bassoon with special emphasis drawn to Panufnik’s understanding of religion in connection with Polish national identity and the national struggle for democratic independence galvanized by the murder of Father Jerzy Popiełuszko in 1984. Panufnik’s relationship with the Polish communist regime, both prior to and after his 1954 defection to England, is explored at length. Each of these aspects informed Panufnik’s compositional approach and the expressive qualities inherent in the Concerto for Bassoon. The Concerto for Bassoon was commissioned by the Polanki Society of Milwaukee, Wisconsin and was premiered by the Milwaukee Chamber Players, with Robert Thompson as the soloist. While Panufnik intended the piece to serve as a protest against the repression of the Soviet government in Poland, the U. S. -

Van Cott Information Services (Incorporated 1990) Offers Books

Clarinet Catalog 9a Van Cott Information Services, Inc. 02/08/08 presents Member: Clarinet Books, Music, CDs and More! International Clarinet Association This catalog includes clarinet books, CDs, videos, Music Minus One and other play-along CDs, woodwind books, and general music books. We are happy to accept Purchase Orders from University Music Departments, Libraries and Bookstores (see Ordering Informa- tion). We also have a full line of flute, saxophone, oboe, and bassoon books, videos and CDs. You may order online, by fax, or phone. To order or for the latest information visit our web site at http://www.vcisinc.com. Bindings: HB: Hard Bound, PB: Perfect Bound (paperback with square spine), SS: Saddle Stitch (paper, folded and stapled), SB: Spiral Bound (plastic or metal). Shipping: Heavy item, US Media Mail shipping charges based on weight. Free US Media Mail shipping if ordered with another item. Price and availability subject to change. C001. Altissimo Register: A Partial Approach by Paul Drushler. SHALL-u-mo Publications, SB, 30 pages. The au- Table of Contents thor's premise is that the best choices for specific fingerings Clarinet Books ....................................................................... 1 for certain passages can usually be determined with know- Single Reed Books and Videos................................................ 6 ledge of partials. Diagrams and comments on altissimo finger- ings using the fifth partial and above. Clarinet Music ....................................................................... 6 Excerpts and Parts ........................................................ 6 14.95 Master Classes .............................................................. 8 C058. The Art of Clarinet Playing by Keith Stein. Summy- Birchard, PB, 80 pages. A highly regarded introduction to the Methods ........................................................................ 8 technical aspects of clarinet playing. Subjects covered include Music ......................................................................... -

Harrison Birtwistle Selected Reviews

Harrison Birtwistle Selected Reviews The Last Supper BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra (January 2017) "The Last Supper was designed as a millennial work. Convened by Ghost (Susan Bickley), Jesus and his disciples survey some of the miseries visited upon the world since their last meeting in Jerusalem. References to looking through “the three zeros of the year 2000” sounded awkward at the time, as did the hurried apologies to “Jews, blacks, Aborigines, women, gypsies [and] homosexuals”, but Birtwistle’s music has worn well. Its heft and humour spring from the page in sharp flecks of pizzicato strings, sinister tattoos from the side drum, coppery, cimbalom-like chords and thick knots of sound from double basses, low woodwind and accordion. The choral writing (sung by the BBC Singers) is superb." - Anna Picard, The Times **** "When The Last Supper was new, in a pre-9/11 world, some of its concerns felt outmoded. How wrong we were. Now it has proved its enduring pertinence." - Fiona Maddocks, The Observer "Birtwistle’s music feels tremendously lyrical, even opulent 17 years after the opera’s premiere. It’s quite often blunt and uncompromising, but the Latin choral motets that accompany Christ’s three visions summon remarkable poise and focus in his choral writing, and his lengthy foot-washing scene, in which Christ humbles himself before each of his disciples in turn, has an astonishing sense of pathos even amid its wailing orchestration that’s only increased by its inexorable repetitions." - David Kettle, The Arts Desk ***** "Birtwistle’s ritualistic writing is marvellous, layer upon layer of skewed time and perspective underpinned by a grim, grand pace unfolding from the bottom of orchestra. -

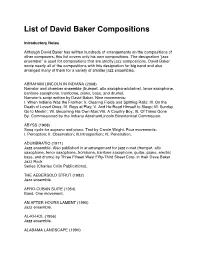

List of David Baker Compositions

List of David Baker Compositions Introductory Notes Although David Baker has written hundreds of arrangements on the compositions of other composers, this list covers only his own compositions. The designation “jazz ensemble” is used for compositions that are strictly jazz compositions. David Baker wrote nearly all of the compositions with this designation for big band and also arranged many of them for a variety of smaller jazz ensembles. ABRAHAM LINCOLN IN INDIANA (2008) Narrator and chamber ensemble (trumpet, alto saxophone/clarinet, tenor saxophone, baritone saxophone, trombone, piano, bass, and drums). Narratorʼs script written by David Baker. Nine movements: I. When Indiana Was the Frontier; II. Clearing Fields and Splitting Rails; III. On the Death of Loved Ones; IV. Boys at Play; V. And He Read Himself to Sleep; VI. Sunday Go to Meetinʼ; VII. Becoming His Own Man;VIII. A Country Boy; IX. Of Times Gone By. Commissioned by the Indiana AbrahamLincoln Bicentennial Commission. ABYSS (1968) Song cycle for soprano and piano. Text by Carole Wright. Four movements: I. Perception; II. Observation; III.Introspection; IV. Penetration. ADUMBRATIO (1971) Jazz ensemble. Also published in anarrangement for jazz nonet (trumpet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, trombone, baritone saxophone, guitar, piano, electric bass, and drums) by Three Fifteen West Fifty-Third Street Corp. in their Dave Baker Jazz Rock Series (Charles Colin Publications). THE AEBERSOLD STRUT (1982) Jazz ensemble. AFRO-CUBAN SUITE (1954) Band. One movement. AN AFTER HOURS LAMENT (1990) Jazz ensemble. AL-KI-HOL (1956) Jazz ensemble. ALABAMA LANDSCAPE (1990) Bass-baritone and orchestra. Text by Mari Evans. Commissioned by William Brown. -

A Performer's Guide to Multimedia Compositions for Clarinet and Visuals: a Tutorial Focusing on Works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2003 A performer's guide to multimedia compositions for clarinet and visuals: a tutorial focusing on works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O. Smith, and Reynold Weidenaar. Mary Alice Druhan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Druhan, Mary Alice, "A performer's guide to multimedia compositions for clarinet and visuals: a tutorial focusing on works by Joel Chabade, Merrill Ellis, William O. Smith, and Reynold Weidenaar." (2003). LSU Major Papers. 36. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/36 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO MULTIMEDIA COMPOSITIONS FOR CLARINET AND VISUALS: A TUTORIAL FOCUSING ON WORKS BY JOEL CHADABE, MERRILL ELLIS, WILLIAM O. SMITH, AND REYNOLD WEIDENAAR A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Mary Alice Druhan B.M., Louisiana State University, 1993 M.M., University of Cincinnati