CHRIST CHURCH LIBRARY NEWSLETTER Volume 10, Issues 1,2 and 3 2017 - 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

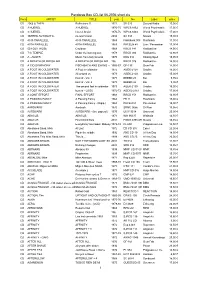

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

John A. T. Robinson - Redating the New Testament (1976)

John A. T. Robinson - Redating the New Testament (1976) FREE ONLINE BOOKS ON FULFILLED PROPHECY AND FIRST CENTURY HISTORY Materials Compiled by Todd Dennis Redating the NEW TESTAMENT Written in 1976 By John A.T. Robinson (1919-1983) Prepared by Paul Ingram and Todd Dennis "One of the oddest facts about the New Testament is that what on any showing would appear to be the single most datable and climactic event of the period - the fall of Jerusalem in AD 70, and with it the collapse of institutional Judaism based on the temple - is never once mentioned as a past fact. " For my father arthur william robinson who began at Cambridge just one hundred years ago file:///E|/2006_Websites/www_preteristarchive_com/Books/1976_robinson_redating-testament.html (1 of 323)12/18/2006 4:36:34 PM John A. T. Robinson - Redating the New Testament (1976) to learn from Lightfoot, Westcott and Hort, whose wisdom and scholarship remain the fount of so much in this book and my mother mary beatrice robinson who died as it was being finished and shared and cared to the end. Remember that through your parents you were born; What can you give back to them that equals their gift to you? Ecclus.7.28. All Souls Day, 1975 CONTENTS Preface Abbreviations I Dates & Data II The Significance of 70 III The Pauline Epistles IV Acts & the Synoptic Gospels V The Epistle of James VI The Petrine Epistles & Jude VII The Epistle to the Hebrews VIII The Book of Revelation IX The Gospel & Epistles of John X A Post-Apostolic Postscript XI Conclusions & Corollaries Envoi file:///E|/2006_Websites/www_preteristarchive_com/Books/1976_robinson_redating-testament.html (2 of 323)12/18/2006 4:36:34 PM John A. -

I Corinthians 6:19

I BELONG TO THE CHURCH "Ye are not your own." I Corinthians 6:19 Paul is telling these Corinthian'Christians that they do not belong to themselves. What he said to them he is saying to you and me. This is true of all mankind. No man belongs to himself. No man has a right to live his own life. We are bound up in a bundle of life with others. You are not your own is a fundamental that we cannot ignore except at our own peril. I. While the fact of our belonging to others is inherent in our very exist- ence, yet, this belonging never comes to its best except when it is acknowledged and willingly accepted by ourselves. Many a master has owned a slave ri~hout L that slave in the fUllest sense belonging to ~ master. Many a man has been man's slave and yet God's free:Jnan at the same time. No man can belong in the fUllest sense without his consent. "Stone walls do not a prison make nor iron bars a cage." We recognize this in the ordinary affairs of life. 1. For instance I was born in an old fashioned country home. I was drop- ped into the arms of a sweet Irish mother.~~se eyes were homes of silent prayer and whose lips were full of delicious laughter. I inherited a rugged h lelong to the Church" Page 2 father, a bit of a puritan, who was aSgentle as he was strong and as strong as he was gentle. -

Contact Between Paul and the Jerusalem Church

Durham E-Theses Paul, Antioch, and Jerusalem: a study in relationships and authority in earliest Christianity Taylor, Nicholas Hugh How to cite: Taylor, Nicholas Hugh (1990) Paul, Antioch, and Jerusalem: a study in relationships and authority in earliest Christianity, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5959/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract Nicholas Hugh Taylor PAUL, ANTIOCH, AND JERUSALEM A Study ir\ Relationships and Authority in Earliest Christianity University of Durham Ph.D. thesis 1990 Paul's life and work, including his relationship with the Jerusalem church, were dynamic, rather than having been predetermined in his conversion. The Antiochene church was crucial to Paul's development, to a degree not previously appreciated. Little is known of the years following Paul's conversion, other than it was unsettled, and included travels and sojourns in Arabia, Damascus, Jerusalem, and Tarsus. -

Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians PAUL's FIRST EPISTLE to THE

PAUL’S FIRST EPISTLE TO THE CORINTHIANS PAUL’S F IRST EP ISTLE TO THE COR INTHIAN S Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians PAUL’S FIRST EPISTLE TO THE CORINTHIANS A Church in Crisis by David Ethan Cambridge Copyright 2006 D.E. Cambridge All rights reserved. No part of this booklet may be stored or reproduced in any form without the written permission from the author. IT IS ILLEGAL AND UNETHICAL TO DUPLICATE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Title Lesson Page Introduction 7 A Historical and Social Background of Corinth 9 SECTION ONE: Concerning Things Reported Greetings and Thanksgiving (1:1-9) 1 17 Factions in the Church (1:10-4:21) 2 23 Morality in the Church (5:1-6:20) 3 43 Incest (5:1-13) Litigations (6:1-11) Fornication (6:12-20) SECTION TWO: Concerning Things Asked Concerning Marriage (7:1-40) 4 59 Marital Obligations (7:1-7) Advice to Special Groups (7:8-16) One’s Calling and Station in Life (7:17-24) Regarding Virgins and Widows (7:25-40) Christian Liberties (8:1-11:1) 5 75 Meat Sacrificed to Idols (8:1-13) Paul’s use of Liberty (9:1-23) The Peril of the Strong (9:24-10:22) Final Statement of Principles (10:23-11:1) Conduct in the Assembly (11:2-14:40) 6 99 The Head Covering (11:2-16) The Lord’s Supper (11:17-34) Spiritual Distinctions (12:1-14:40) The Resurrection (15:1-58) 7 139 SECTION THREE: Final Instructions and Comments The Collection (16:1-4) 8 157 Closing Comments and Greetings (16:5-24) 9 163 ARTICLES Command or Custom by H.O. -

A U D I O T E

A U D I O T E C A Listagem dos cd´s por titulo DELEGAÇÃO DE LISBOA TITULO ARTISTA/GRUPO Nº A CAETANO VELOSO 898 A ALMA DA RUSSIA TCHAIKOVSKY 781 A DANADA SOU EU LUDMILLA 1336 A DAY WITHOUT RAIN ENYA 237 A FLAUTA MÁGICA WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART 718 A GIRL LIKE ME RIHANNA 1000 A HISTÓRIA SÉTIMA LEGIÃO 245 A HISTÓRIA DA SÉTIMA LEGIÃO II SÉTIMA LEGIÃO 418 A HISTÓRIA TODA LUÍS REPRESAS 904 A IDADE DA INOCÊNCIA COLECTANEAS 526 A LIVE JUST FOR LOVE PETER MURPHY 983 A MÃE RODRIGO LEÃO & CINEMA ENSEMBLE 1049 A MAGIA DO PIANO CHOPIN 679 A MAIA DA MÚSICA MOZART 832 A MEMÓRIA DO AMOR TOZÉ BRITO 1327 A MONTANHA MÁGICA RODRIGO LEÃO 1133 A MOON SHAPED POOL RADIOHEAD 1286 A NIGHT WITH LOU REED LOU REED 5012 À NOITE CARLOS DO CARMO 957 A PALMA E A MÃO JOÃO PEDRO PAIS 988 A THOUSAND SUNS LINKIN PARK 1090 A TRAGÉDIA NA ÓPERA PUCCINI 713 A WONDERFUL LIFE LARA FABIAN 532 ABBA GOLD ABBA 1002 ABRIENDO PUERTA GLORIA ESTEFAN 278 ACOUSTIC SONGBOOK COLECTANEAS 556 ACÚSTICA SÓ PARA CONTRARIAR 370 ACÚSTICO AO VIVO WANDO 493 ACÚSTICO EM TRANCOSO IVETE SANGALO 1304 ADELE 25 ADELE 1276 AFRICANDO MARTINA 444 ÁGATA AO VIVO ÁGATA 1236 AIDA GIUSEPPE VERDI 691 AINDA MADREDEUS 1005 AL OTRO LADO HEVIA 210 ALAN PARSONS LIVE ALAN PARSONS 29 ALCIONE ALCIONE 723 ALEJANDRO SANZ - COLECCIÓN DEFINITIVA ALEJANDRO SANZ 1136 ALL I REALLY WANT TO DO CHER 406 ALL MY HITS HELENA 648 ALL THAT I AM SANTANA 674 ALL THAT YOU CAN'T LEAVE BEHIND U2 227 ALL THE BEST PAUL McCARTNEY 233 ALL THE BEST TINA TURNER 581 Delegação de Lisboa, 09/04/2019 Pag. -

Oil Embargo Lift Seen WASHINGTON (AP) - the Current $11.65, It Was Removed and Full Produc- the Political Crisis in Israel Similar Syrian Mission

Jol> Limit Action Slm> ila/idl ers The Weather Mostly cloudy, windy and THEDAILY very mild with afternoon FINAL showers likely. Clear, cool- er tonight; partly sunny EDITION and mild tomorrow I J 16 PACKS Monmoulh I ounly*« Outstanding Home Newspaper Plu» Tabloid VOL 96 NO. 176 RED BANK-MIDDLETOWN, N.J.Tl ESOAY.M tlCM 3,1971 TEN CENTS • IIIIMIIIIMIIHIHMIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIilMIIIIMIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIMIMIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIMIIIIIIMIIIIIIIIIHIIMIIIIIIIIIIIIHIIIIIIIMIIMIIIIIIIIIIIIIIHHIIIIIIIIII Port Foes Fear Committee ^MindMade Up' By SHERRY FIGDORE \of Elizabeth, told assem- D-Essex, and Sen Eugene NJEA's 75,000 members, "I got the feeling." Dr. mittee has already decided local hearing. Brilliant said the figures bled witnesses and onlook- Bedell, D-Mon, would of- Dr. Weisberg had told the Weisberg said later, "that I the outcome of the hear- Martin B Brilliant of worked out to savings of I TRKNTON - Members jers at yesterday's second fer a solution to the energy committee, objected to the was being questioned by • ings and that fad should be Ijolmdel representing the cent per gallon of gasoline of a Senate committee nearing here on Senate bill crisis. port because it would group of men who have considered ai count y Committee for a Better at the consumer level holding public hearings on ^S-200 that the committee Dr. Dalai also demanded threaten the coastal envi- their minds made up." groups prepare for the Environment, disputed in- (ierald A Hansler, re- a proposed oilport off New * had "other things to conern a statewide master plan ronment -

Cicero Illustratus: John Toland and Ciceronian Scholarship in the Early Enlightenment

Cicero Illustratus: John Toland and Ciceronian Scholarship in the Early Enlightenment KATHERINE EAST Thesis submitted to the Department of Classics, Royal Holloway, University of London, for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Declaration of Authorship I, Katherine East, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: ABSTRACT In 1712 the radical intellectual John Toland wrote a treatise entitled Cicero Illustratus, which proposed a new edition of Cicero’s complete works. In this text Toland justified and described his plans; as a result such varied issues as the Ciceronian tradition in eighteenth century culture, the nature of scholarship in this period, and the value of Ciceronian scholarship to Toland’s intellectual efforts were encompassed. In spite of the evident potential of Cicero Illustratus to provide a new perspective on these issues, it has been largely neglected by modern scholarship. This thesis rectifies that omission by establishing precisely what Toland hoped to achieve with Cicero Illustratus, and the significance of his engagement with Ciceronian scholarship. The first section of the thesis addresses Cicero Illustratus itself, discovering Toland’s aims by evaluating his proposals against both the existing Ciceronian editorial tradition and his immediate scholarly context. This reveals that Toland used his engagement with scholarship to simultaneously construct authority for his professed rehabilitation of the real Cicero, and for himself as an interpreter of this ‘real’ Cicero. The second section of this thesis demonstrates the broader purpose of this exploitation of erudition; it allowed Toland to construct Cicero as a vital weapon in his radical discourse on politics and religion. -

Microsatellite Genotyping in New Zealand's Poplar and Willow

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Microsatellite Genotyping in New Zealand’s Poplar and Willow Breeding Program: Fingerprinting, Genetic Diversity and Rust Resistance Marker Evaluation A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Plant Breeding at Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand. Duncan MCLEAN 2019 1 ABSTRACT Poplars (Populus spp.) and willows (Salix spp.) are the most employed sustainable soil stabilisation tools by the pastoral sector in New Zealand. The poplar and willow breeding program at the New Zealand Institute for Plant & Food Research Limited (PFR) supports and improves the versatility of poplars and willows as soil stabilisation tools. Good germplasm management involves being able to accurately and objectively identify breeding material and characterise genetic diversity and relationships. Poplar rust is the primary pathogen of concern for the breeding program and evaluating candidate resistance markers could improve selection efficiency. We employed microsatellite markers to fingerprint and characterise the genetic diversity of the germplasm collection. In addition, we also evaluated SSR marker ‘ORPM277’s potential usefulness as a molecular marker to screen for rust resistance in New Zealand. We found that most microsatellite markers utilised in this study were moderately to highly polymorphic with Polymorphic Information Content values averaging 0.482 and 0.497 in the poplar and willow collections respectively. A DNA fingerprinting database was generated that differentiated between 95 poplar accessions and 197 willow accessions represented by 19 and 55 species groups respectively. -

T I IWESTFIELD LEADER

T ipq IWESTFIELD LEADER HOB JiiJ f*« i*«4sif «n4 JfMf IfWe/if Circulated Weekly Newipaperln Vnion County pq HI usnuo» NINETY-S: nmw O. 30 Stcoad Cl«4 Poum PM Published "* HH. N.I. WESTFIELD, NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 1986 20 Pages—30 Cents O- ** 33 Every Thursday irdwick is Sworn in as Consultant Appointed for Acting Governor of New Jersey Assembly Speaker Chuck Hardwick served as acting business representatives and Nationwide Superintendent Search Hardwick of Westfield has horn governor on Thursday and Fri- other officials. sworn to serve as acting gover- Dr. Carroll F. Johnson, senior Wilmette, III.; Fairfax. Va.; New to his help in our search for the day, Feb. 6-7 as Kean traveled to consultant from the Education Rochelle, N.Y.: Darien, Conn.; nor of New Jersey when Gov. Washington, D.C., to meet with An acting governor is needed in best superintendent available'for Thomas H. Kean is out of the the state when the governor is and Management Services and Tenalfy and Princeton. New Westfield," he continued. federal, state, county and local Department of the National Jersey. state. legislators from New Jersey. away to head the government Taylor said that eight consult- should any emergency arise. "He School Boards Association, has The consulting service includes ants had submitted applications also fills in for the governor nt been appointed consultant in the ten tasks; for the job. Members of the events that are scheduled during nationwide search for a new * initial meeting of NSBA con- Staff/Citizen Superintendent the absence." said Hardwirk. superintendent of schools for sultant with the School Board, Search Committee reviewed the R-Uninn. -

Principles of the Ecology

http://ecopri.ru http://petrsu.ru Publisher FSBEI of HE “Petrozavodsk State University” Russian Federation, Petrozavodsk, pr. Lenina,33 Scientific journal PRINCIPLES OF THE ECOLOGY http://ecopri/ru Vol. 5. № 3 (19). September, 2016 Editor in Chief A. V. Korosov Editorial Council Scientific editors Staff V. N. Bolshakov G. S. Antipina A. G. Marachtanov A. V. Voronin A. E. Veselov E. V. Golubev E. V. Ivanter T. O. Volkova S. L. Smirnova N. N. Nemova E. P. Ieshko T. V. Ivanter G. S. Rosenberg V. A. Ilyukha N. D. Chernysheva A. F. Titov N. M. Kalinkina A. M. Makarov A. Yu. Meigal ISSN 2304-6465 Address editorial board 185910, Republic of Karelia, Petrozavodsk, ul. Anokhin, 20. Room 208 E-mail: [email protected] http://ecopri/ru FSBEI of HE “Petrozavodsk State University” Principy èkologii. 2016. Vol. 5. № 3. http://ecopri.ru http://petrsu.ru Table of Contents Vol. 5. Is. 3. 2016. Editorial notes 3 Foreword 4 Igor Aleksandrovich Shilov 5 List of abstracts of the II International 6-16 scientific conference “Population ecology of animals” dedicated to the memory of academician I.A. Shilov Abstracts 17-164 Alphabetical index 165-168 2 Principy èkologii. 2016. Vol. 5. № 3. From the editorial board Dear readers, authors and reviewers! The third issue of the journey presents the materials of the Second International Conference "Population Ecology of Animals", dedicated to the memory of Ivan Shilov. Reviewing, editorial preparation and makeup were carried out by the organizing committee of the conference. The correct link to the collection: II International scientific conference "Population Ecology of Animals", dedicated to the memory of Academician I.A.