Review of Discernment Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australians Begin ‘Ad Limina’ Visits Acknowledging

Australians begin ‘ad limina’ visits acknowledging impact of crisis VATICAN CITY (CNS) — The president of the Australian bishops’ conference told his fellow bishops that it is “a time of humiliation” for Catholic Church leaders, but he is convinced that God is still at work. As church leaders continue to face the reality of the clerical sexual abuse crisis and attempts to cover it up, “we as bishops have to discover anew how small we are and yet how grand is the design into which we have been drawn by the call of God and his commissioning beyond our betrayals,” said Archbishop Mark Coleridge of Brisbane, conference president. After a weeklong retreat near Rome, the bishops of Australia began their “ad limina” visits to the Vatican with Mass June 24 at the tomb of St. Peter and a long meeting with Pope Francis. The 38-member group included diocesan bishops, auxiliary bishops, the head of the ordinariate for former Anglicans and a diocesan administrator. Archbishop Coleridge was the principal celebrant and homilist for the Mass in the grotto of St. Peter’s Basilica marking the formal beginning of the visit. The “ad limina” visit is a combination pilgrimage — with Masses at the basilicas of St. Peter, St. Mary Major and St. Paul Outside the Walls — and series of meetings with Pope Francis and with the leaders of many Vatican offices to share experiences, concerns and ideas. The visits traditionally were required of bishops every five years, but with the increased number of dioceses and bishops around the world that is no longer possible. -

CTC Community News Tolle Lege

CTC Community News Tolle Lege December 2019 . Community news An eventful year ends in prayer and thanksgiving On Friday 8 November, the CTC community gathered in the Knox Lecture Room for the End-of-Year Mass, which was celebrated this as a Votive Mass of the Holy Spirit. As the academic year drew to a close, this was a wonderful opportunity to come together in the presence of Christ, offering our prayers and thanks as we reflected on the events of the past year and our hopes for the year to come. Our former Master, Bishop Shane Mackinlay, joined us as chief celebrant, and our new Master, Very Rev. Dr Kevin Lenehan, delivered an apt and thoughtful homily (see facing page). The Mass was also an opportunity to present Bishop Shane with the College’s parting gift to him—a beautiful red chasuble and matching mitre. Following the Mass, refreshments were served with the generous assistance of the Student Representative Council, providing another less formal opportunity for the College community to farewell Bishop Shane and welcome Father Kevin to the role of Master of CTC. 3 2 | Tolle Lege . Homily The Holy Spirit and authentic reform In his end-of-year homily, the Master Because there is plenty of Tens of thousands of Catholics and of CTC, Very Rev. Dr Kevin Lenehan, disappointment around, isn’t there? their friends are at work around the reflected on the role of the Spirit in Both inside the church and outside. The country in prayer and conversation renewing the church, and asked how, young and the older, the committed leading up to the National Plenary as a College community, we might and the hangers-on, the disillusioned Council of the Church to meet in participate in this Spirit-moved renewal. -

Why the Delays in Appointing Australia's Bishops?

Why the delays in appointing Australia’s Bishops? Bishops for the Australian mission From 1788, when the First Fleet sailed into Botany Bay, until 31 March 2016, seventeen popes have entrusted the pastoral care of Australia’s Catholics to 214 bishops. Until 1976 the popes had also designated Australia a ‘mission’ territory and placed it under the jurisdiction of the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide which largely determined the selection of its bishops. The first five bishops never set foot on Australian soil. All English, they shepherded from afar, three from London, and two from the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa where, from 1820 to 1832, they tendered their flock in distant New Holland and Van Diemen’s Land via priest delegates. The selection and appointment in 1832 of Australia’s first resident bishop, English Benedictine John Bede Polding, as Vicar Apostolic of New Holland and Van Diemen’s Land, was the result of long and delicate political and ecclesiastical negotiations between Propaganda, the British Home Secretary, the Vicars Apostolic of the London District and Cape of Good Hope, the English Benedictines, and the senior Catholic clerics in NSW. The process was repeated until English candidates were no longer available and the majority Irish Catholic laity in Australia had made it clear that they wanted Irish bishops. The first Irish bishop, Francis Murphy, was appointed by Pope Gregory XVI in 1842, and by 1900, another 30 Irish bishops had been appointed. Propaganda’s selection process was heavily influenced by Irish bishops in Ireland and Australia and the predominantly Irish senior priests in the Australian dioceses. -

V5 RITM0077488 ACU Centre for Liturgy Newsletter Issue 9.Indd

ACU CENTRE FOR LITURGY Newsletter Issue 9, November 2020 FROM THE DIRECTOR IN THIS ISSUE: While the COVID-19 pandemic has seen In this newsletter, preaching educator Liturgy spotlight: many endure a months-long enforced fast Sr Janet Schlichting OP describes the Preaching as an from in-person liturgical celebrations, essential boundaries within which imaginative act a wider-than-usual range of televised creativity can flourish in homily-writing and online liturgies has been available and Rev Dr Richard Leonard SJ shares Sharing good practice: for viewing and virtual participation. practical insights gained over almost The varying quality of these liturgies has thirty years of preaching to highlight how Advice for good preaching spotlighted some excellent liturgical praxis to make the Word of God central to the and some areas in need of further work. homilist’s life and relevant to the lives and News and recent events The homily is one of the most-commented- cultures of those to whom he preaches. upon areas of the liturgy and one where Venite audite! UPCOMING: the wisdom of experienced practitioners Professor Clare V. Online public lecture series: and educator-coaches can provide valuable Johnson Rev Msgr Kevin W. Irwin, insights and strategies for improvement. Director, ACU Professor of Liturgical Studies Those professionals who practise the art Centre for Liturgy and Sacramental Theology at and craft of preaching must consistently Professor of The Catholic University of review and refresh their approach to Liturgical Studies America and author of Pope this aspect of liturgical service because & Sacramental Francis and the Liturgy will the homily is, “necessary for nurturing Theology, Faculty speak as part of the ACU Centre the Christian life” (GIRM #65) and the of Theology & for Liturgy’s new online public homilist’s task is “to proclaim how God’s Philosophy lecture series in May 2021. -

12Th May 2017

Issue 6 2017 From the Principal Mr John M Freeman n Tuesday, last week, we held Twilight Evening. This is an important part of our Oprocesses to let the community know what we offer at Lavalla Catholic College. We had a large number of families attend and feedback was very positive. Thank you to Mrs Kelly Murray and the team at St Paul’s Campus for all their work. The success of these events is not due to anyone person, but the collaborative efforts of everyone – teachers, administration team, maintenance team, our cleaners and very importantly the students. The success of “Open Days” is usually due to the students who are escorting and talking with families or those performing, cooking, demonstrating and simply REFLECTION enjoying themselves whilst being at their school. Like Mary I would like to remind families that enrolment applications are due on 31 May 2017. We will Like Mary of Nazareth accept applications after that date, but as a matter (Luke 2: 39-52), we nurture, of justice priority will be given to those who have guide and care for the submitted their applications on time. young, developing in them a knowledge and love of the God who is active in You would be aware that we were privileged to host their lives, and a respect for two of the Marist Bicentenary Paintings at Lavalla all God has created. Catholic College. We only had opportunity to have the “Fourvière Pledge” and “Dying Boy” from Like her, we accept them as they are even when we Friday afternoon of last week until Tuesday this don’t fully understand their week. -

6Th Sunday in Ordinary Time Year B 14022021

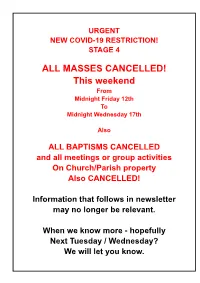

URGENT NEW COVID -19 RESTRICTION! STAGE 4 ALL MASSES CANCELLED! This weekend From Midnight Friday 12th To Midnight Wednesday 17th Also ALL BAPTISMS CANCELLED and all meetings or group activities On Church/Parish property Also CANCELLED! Information that follows in newsletter may no longer be relevant. When we know more - hopefully Next Tuesday / Wednesday? We will let you know. Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time, Year B 14th February 2021 PARISH BULLETIN St Macartan’s Catholic Parish 4 Drake St, Mornington VIC 3931 Parish Office : Tuesday to Friday 9am to 4pm; Ph: 5975 2200 Email: [email protected] Web: stmacartansparish.com.au Parish Priest: Rev. Fr Geoffrey McIlroy Parish Secretary: Theresa Collard Mass Times Parish Contact Details Weekdays: Tues -Sat 9:15am Parish Pastoral Council: Contact Office Saturday: Vigil 6pm . Finance Committee: Frank Crea Sunday: 9am, 11am & 5pm (Youth Mass). 0417 104 041 Child Safety Officer: Carmel McGrath Holy Hour / Adoration 0400 076 067 3:30 to 4:30pm each Sunday and Email: [email protected] Every Friday & on 1st Saturdays each month Volunteer Application Officer: after 9:15am Mass Tim Lambourne - email Office RECONCILIATION: St Macartan’s Social Justice Awareness After the Wed and Sat morning Masses Group: Contact Kerry McInerney Video Sunday Mass [email protected] On Line found on Parish’s YouTube page: 59762155 (Ctrl and enter) on this link: AV Technical: Graeme Wilson https://www.youtube.com/channel/ Email: [email protected] UCW8lyzEMe20DLyOpptks0Fw/videos St Mac’s High Spirits - Faye Melhem Also view our Parish website: Email: [email protected] Parish Caretaker: John Spaziani https://www.stmacartansparish.com.au/ 0419 598 911 Upcoming Holy Days: Music & Wedding Co -Ordinator- • Wed 17th: Ash Wednesday. -

The Swag Theswag.Org.Au | Vol

Quarterly magazine of the National Council of Priests of Australia The Swag theswag.org.au | Vol. 25 No. 1 | Autumn 2017 REGULARS NCP CONTACTS From the NCP Chairman ................................................3 Editorial .....................................................................................4 Letters to the Editor .........................................................32 News ..................................................................................33-36 Reviews ............................................................................37-39 Returned to God .........................................................40-42 FEATURES Chairman Secretary Treasurer Seminary formation and the Rev Jim Clarke Rev Mark Freeman Rev Wayne Bendotti 44 Margaret St Royal Commission ..............................................................5 2 Taylors Lane PO Box 166 Rowville VIC 3178 Launceston TAS 7250 Dardanup WA 6236 Enemy inside the gate ................................................... 6-7 P: (03) 9764 4058 P: (03) 6331 4377 P: (08) 9728 1145 Young people to set agenda for Synod .......................7 F: (03) 9764 5154 F: (03) 6334 1906 F: (08) 9728 0000 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Burdens of office .............................................................. 8-9 Association of Catholic Priests .............................10-11 Bishop Mulkearns – canonist and friend ........11-12 Towards a change of parish contours ................12-14 Back to following -

Delegates of the Fifth Plenary Council for the Church in Australia Adelaide 2020 | Sydney 2021

Delegates of the fifth Plenary Council for the Church in Australia Adelaide 2020 | Sydney 2021 Adelaide . Most Rev Patrick O’Regan, Archbishop-elect . Fr Philip Marshall, Vicar General . Miss Madeline Forde . Ms Monica Conway . Mr Ian Cameron . Mr Julian Nguyen Armidale . Most Rev Michael Kennedy, Bishop . Monsignor Edward Wilkes, Vicar General . Mr Karl Schmude . Mrs Alison Hamilton Ballarat . Most Rev Paul Bird, Bishop . Fr Kevin Maloney, Vicar General . Ms Felicity Knobel . Mrs Marie Shaddock Bathurst . Most Rev Michael McKenna, Bishop . Fr Paul Devitt, Vicar General . Miss Hayley Farrugia . Mr Matthew Brown . Fr Gregory Kennedy, Vicar for Clergy Brisbane . Most Rev Mark Coleridge, Archbishop . Most Rev Kenneth Howell, Auxiliary Bishop . Monsignor Peter Meneely, Vicar General . Ms Toni Janke . Mr Thomas Warren . Dr Meave Heaney . Ms Patricia Kennedy . Fr Adrian Kennedy, Vicar North Country Deanery . Fr Adrian Boyle, Judicial Vicar . Fr Daniel Ryan, Vicar for Clergy . Fr John Grace, Seminary Rector, Holy Spirit melbourne Broken Bay . Most Rev Anthony Randazzo, Bishop . Fr David Ranson, Vicar General . Mrs Alison Newell . Mr Dharmaraj Rajasigam Broome . Fr Paul Boyers, Vicar General . Mr Aidan Mitchell . Ms Erica Bernard Bunbury . Most Rev Gerard Holohan, Bishop . Fr Tony Chiera, Vicar General . Dr Deborah Robertson . Mrs Maria Parkinson Cairns . Most Reverend James Foley, Bishop . Fr Francis Gordon, Vicar General . Mrs Anna Montgomery . Mrs Tanya Gleeson Rodney . Fr Kerry Crowley, Vicar for Southern Deanery and Clergy . Fr Neil Muir, Vicar for Finance, Education and Centacare Canberra-Goulburn . Most Rev Christopher Prowse, Archbishop . Fr Anthony Percy, Vicar General . Monsignor John Woods, Vicar for Education . Miss Brigid Cooney . Prof. John Warhurst Chaldean . -

CTC Community News Tolle Lege

CTC Community News Tolle Lege November 2018 Book launch Sevent y-three books, and counting ... On Wednesday 19 September 2018, Christian theology, the most important A Christology of Religions (Maryknoll, challenge is "to give an account of NY: Orbis), the most recent work of the phenomenon of various religious Honorary Research Fellow Rev. traditions within the world view of Professor Gerald O'Collins SJ AC, salvation history and of God's saving was launched at CTC. Catherine will, personally and escatologically Place was among the guests. enfleshed in the paschal event of Jesus Christ … and embodied now in The Master of the College, Associate the historical mission of the Church." Professor Shane Mackinlay, welcomed He gave an overview of the ways the assembled guests, including in which Professor o'Collins had Professor Gabrielle McMullen, Sir grappled with this challenge over James Gobbo and the Honourable many years in numerous books, John Batt. As he noted, Professor articles and reviews, and drew o'Collins' capacity for forming and particular attention to the many maintaining friendships was evident ways Professor o'Collins has helped in the number of those gathered, people appreciate the contribution and his capacity for intellectual of the Second Vatican Council to work was also evident in his 73 "the Church's understanding of the theological publications—a fine place of other religious traditions in example of "the Church thinking God's revealing and redeeming self- out loud". He thanked him for his communication". contribution to CTC as Honorary Research Fellow and for the interest he takes in the higher degree research students in general as well as those whose work he supervises. -

Members of the Catholic Community in Victoria, E Catholic Dioceses Of

CATHOLIC DIOCESE of BALLARAT CATHOLIC DIOCESE CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF SANDHURST OF SALE Wednesday 25 August 2021 Members of the Catholic community in Victoria, !e Catholic Dioceses of Melbourne, Ballarat, Sandhurst and Sale, Dear brothers and sisters in Christ, We hold the people of Afghanistan in our prayers, and express a commitment to compassionate outreach for them throughout the world and here in Victoria. In Victoria, we have the largest number of Afghan-born people in Australia and have two ‘world famous’ places deeply enriched by Afghan culture: Dandenong and Shepparton. Afghans hold an important place in the hearts of Victorians, especially at this di"cult time. We recognise the pain of family separation, and are deeply concerned for those who are living in safety in Australia while their homeland experiences such rapid and devastating changes. We know there is deep concern from the Afghan community in Victoria for their family members and friends who remain in Afghanistan. We join with them in this concern. While we recognise the limitations of the role that Australia can play in the context of this international crisis, and the complexity of the situation, we a"rm that a just and compassionate response should guide our Government’s decision making. Our country’s involvement in the con#ict should urge a just and compassionate response to the current situation now, and our policies should be person-focused, and adapt to the fundamentally changed situation. Families being able to be together safely should be a priority at this time. We hold particularly in our prayers the 5,100 Afghan refugees in the Australian community who are separated from family and loved ones because of the danger related to their own personal situations that required them to leave their homes and families, and by the continuing Australian Government policy that precludes them from applying for humanitarian visas for their immediate family members to join them in safety in Australia. -

CECV Strategic Plan 2015–2019

CECV Strategic Plan 2015–2019 Flourishing Catholic school children, families and communities living life to the full Schools featured in photos First published 2015 Damascus College, Mount Clear Emmanuel College Inc., Warrnambool Catholic Education Commission of Victoria Ltd Galen Catholic College, Wangaratta James Goold House Holy Rosary School, White Hills 228 Victoria Parade Mary MacKillop Catholic Regional College, Leongatha East Melbourne VIC 3002 Mary MacKillop School, Narre Warren North www.cecv.catholic.edu.au Nazareth College, Noble Park Our Lady of Lourdes School, Prahan East St Joseph’s School, Warragul Correspondence to: St Kieran’s School, Moe The Company Secretary St Mary of the Angels College, Nathalia Catholic Education Commission of Victoria Ltd St Mary of the Cross School, Point Cook PO Box 3 St Mary’s School, Malvern East EAST MELBOURNE VIC 8002 St Mary’s School, Rutherglen Email: [email protected] St Mary’s School, Yarram Salesian College, Sunbury ACN 119 459 853 ABN 92 119 459 853 © Catholic Education Commission of Victoria Ltd 2015 Licensed under NEALS future CECV Strategic Plan 2015–2019 2 Contents Executive Summary 4 Letter of Mandate 5 The Company: The Catholic Education 6 Commission of Victoria Ltd – Members of the Company – Directors of the Company – Objects of the Company Vision 7 – Mission – Values and Operational Principles Challenges Facing the Sector 9 Priorities 10 Strategies 10 Strategic Plan Matrix 11 Appendix 1: Canon Law References to 12 the vision and mission of Catholic education Appendix -

St Vincent De Paul Press

BOOK LAUNCH St. Vincent de Paul Parish Listening, Learning and Leading: The Impact of St Vincent de Paul Press Prayer Catholic Identity and Mission Thursday 22 May 2014, 5pm - 6pm, Edited by Gabrielle McMullen Loving God, through St Vincent 17th & 18th May, 2014 and John Warhurst this book explores the impact of de Paul, we seek your guidance Fifth Sunday of Easter identity and mission on what we do and how we do and constant protection, The Weekly Bulletin of the Parish of St Vincent de Paul, Strathmore it. Contributors include: David Beaver, Fr Frank for our parish community. Parish Priest: Fr Peter J Ray Fr Peter Email : [email protected] Brennan sj, Vicki Clark, Bob Dixon, Julie Edwards, Parish Administration: Mrs. Patricia McNicholl Parish Office Email : [email protected] Hon Tim Fischer, Denis Fitzgerald, Sr Margaret Gathered together as your people, Presbytery: 2 The Crossway, Strathmore, Victoria 3041 Web : cam.org.au/strathmore Mary Flynn ibvm, Jenny Glare, Fr Andy Hamilton we come as we are, Telephone : 9379 1488 Facsimile: 9379 1574 sj, Peter Hudson, Chris Lowney, Michael McGirr, to live out the Gospel message, St Vincent de Paul Primary School: Woodland Street, Strathmore, 3041 Julie Morgan. Listening, Learning and Leading: The in a faithfilled, welcoming Principal: Mr John Grant Impact of Catholic Identity and Mission will be and caring community. Telephone : 9379 5723 Facsimile: 9379 2389 Email: [email protected] launched by Archbishop Denis Hart Cardinal Knox Sunday Mass : Saturday Vigil : 6.00 pm Sunday Morning : 8.30 am & 10.30 am Centre, 383 Albert St, East Melbourne Grant us your help in our weak- Weekday Masses: Tuesday - Saturday 10.00 am RSVP: Thursday 15 May Contact: Lucia Brick: 287 ness, that we may proclaim to all, Blessed Sacrament Chapel: Open Tuesday - Saturday 7.00 am - 5.00 pm for private prayer 5566 or [email protected] your abundant goodness.