Planning: Move by Move Annotated Games Contained a Lot of Prose and Few Variations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Los Angeles to Reykjavik

FROM LOS ANGELES CHAPTER 5: TO REYKJAVIK 1963 – 68 In July 1963 Fridrik Ólafsson seized a against Reshevsky in round 10 Fridrik ticipation in a top tournament abroad, Fridrik spent most of the nice opportunity to take part in the admits that he “played some excellent which occured January 1969 in the “First Piatigorsky Cup” tournament in games in this tournament”. Dutch village Wijk aan Zee. five years from 1963 to Los Angeles, a world class event and 1968 in his home town the strongest one in the United States For his 1976 book Fridrik picked only Meanwhile from 1964 the new bian- Reykjavik, with law studies since New York 1927. The new World this one game from the Los Angeles nual Reykjavik chess international gave Champion Tigran Petrosian was a main tournament. We add a few more from valuable playing practice to both their and his family as the main attraction, and all the other seven this special event. For his birthday own chess hero and to the second best priorities. In 1964 his grandmasters had also participated at greetings to Fridrik in “Skák” 2005 Jan home players, plus provided contin- countrymen fortunately the Candidates tournament level. They Timman showed the game against Pal ued attention to chess when Fridrik Benkö from round 6. We will also have Ólafsson competed on home ground started the new biannual gathered in the exclusive Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles for a complete a look at some critical games which against some famous foreign players. international tournament double round event of 14 rounds. -

Solingen (Unregular)

Solingen (unregular) International tournaments 1968 (100th anniversary tournament of the Solingen Chess Club) Lengyel clear first, ahead of 2. Parma, 3.-7. Pachman, Szabo, Damjanovic, Janosevic (16 players, including O’Kelly, Donner, Medina, Tatai, Lehmann, and Wade who wrote a tournament book; IM Gerusel shared 8th place). This was maybe Levente Lengyel’s (GM in 1964) finest tournament win, he also won at Rome 1964 (joint with Lehmann), Bari 1972 outright, and Reggio Emilia 1972/73 (joint with Popov and Torre). MATHIAS GERUSEL (born Feb-05-1938) Germany Mathias Gerusel is a (West) German IM who finished second to William James Lombardy at the World Junior Championship (1967). He went on to study mathematics. His best tournament results have been 3rd at Büsum 1969 after Bent Larsen and Lev Polugaevsky, and 5th= at Solingen 1974. 1974 Polugaevsky, Kavalek, ahead of 3.-4. Spassky, Kurajica, (15 players, Pachman boycotted), IM Gerusel shared 5th place together with Szabo, Liberzon, and Westerinen, above 9. Uhlmann; including also Heinz Lehmann, and Hajo Hecht) ttp://www.teleschach.de/historie/solingen1974.htm (Standings) http://www.zeit.de/1974/30/der-ausdruck-des-bedauerns (Boycott of Pachman) 1986 (international club championship) Hübner clear first, ahead of 2./3. IM Ralf Lau, Short (Lau beat Short in their direct game) 4. Kavalek, 5.-6 Spassky, IM Lucas Brunner, 7.-8. Sunye-Neto, Westerinen (12 players, among them German IM Capelan who played already in 1968 and in 1974). Note: Brunner vs. Schneider (https://www.365chess.com/game.php?gid=2169447) has a wrong score, Brunner won Ralf Lau achieved his third an final GM norm to become a grandmaster. -

Palma De Mallorca (1965-1972) Botvinnik, Smyslov, Petrosian, Spassky Not Winning !

Palma de Mallorca (1965-1972) Botvinnik, Smyslov, Petrosian, Spassky not winning ! YEAR WINNER COUNTRY POINTS Arturo Pomar Salamanca * Spain 1965 Albéric O'Kelly Belgium 6'5/9 Klaus Darga Germany 1966 Mikhail Tal USSR 12/15 1967 Bent Larsen Denmark 13/17 1968 Viktor Korchnoi USSR 14/17 1969 Bent Larsen Denmark 12/17 1970 Bobby Fischer USA 18'5/23 (IZT) Ljubomir Ljubojevic * Yugoslavia 1971 11/15 Oscar Panno Argentina Oscar Panno * Argentina 1972 Jan Smejkal Czechoslovakia 10/15 Viktor Korchnoi USSR Eight editions of Palma, annually from 1965 to 1972 (including the Interzonal from 1970). Twice winners at Palma de Mallorca are Bent Larsen, Viktor Korchnoi, and Oscar Panno. Note: All post-war World Chess Champions (then) did participate at Palma de Mallorca series: Botvinnik, Smyslov, Tal (winner 1966), Petrosian, Spassky, and Fischer (winner of IZT 1970), meaning no less than four World Chess Champions did play but not win at Palma de Mallorca. Legendary Oscar Panno, the first Argentine-born grandmaster, winner at Palma 1971 & 1972 Palma de Mallorca – survey by Jan van Reek, endgame.nl Pgn Chess tournaments in Palma de Mallorca Cb-file chess tournaments in Palma de Mallorca An annual international chess tournament happened in Palma de Mallorca, the birthplace of Arturo Pomar. The first installment lasted from 15 until 23 xi 1965. Ten men participated in a modest field. Pomar Salamanca (participating six times in 1965, 1966, 1968, 1969, 1971, 1972) won on tie-break. The second Palma de Mallorca tournament had a much larger budget. Sponsors were Hotel Jaime I, Palma tourist industry, Spanish chess federation and Asociacion de la Prenza. -

3 Fischer Vs. Bent Larsen

Copyright © 2020 by John Donaldson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. First Edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Donaldson, John (William John), 1958- author. Title: Bobby Fischer and his world / by John Donaldson. Description: First Edition. | Los Angeles : Siles Press, 2020. Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020031501 ISBN 9781890085193 (Trade Paperback) ISBN 9781890085544 (eBook) Subjects: LCSH: Fischer, Bobby, 1943-2008. | Chess players--United States--Biography. | Chess players--Anecdotes. | Chess--Collections of games. | Chess--Middle games. | Chess--Anecdotes. | Chess--History. Classification: LCC GV1439.F5 D66 2020 | DDC 794.1092 [B]--dc23 Cover Design and Artwork by Wade Lageose a division of Silman-James Press, Inc. www.silmanjamespress.com [email protected] CONTENTS Acknowledgments xv Introduction xvii A Note to the Reader xx Part One – Beginner to U.S. Junior Champion 1 1. Growing Up in Brooklyn 3 2. First Tournaments 10 U.S. Amateur Championship (1955) 10 U.S. Junior Open (1955) 13 3. Ron Gross, The Man Who Knew Bobby Fischer 33 4. Correspondence Player 43 5. Cache of Gems (The Targ Donation) 47 6. “The year 1956 turned out to be a big one for me in chess.” 51 7. “Let’s schusse!” 57 8. “Bobby Fischer rang my doorbell.” 71 9. 1956 Tournaments 81 U.S. Amateur Championship (1956) 81 U.S. Junior (1956) 87 U.S Open (1956) 88 Third Lessing J. -

Brekke the Chess Saga of Fridrik Olafsson

ØYSTEIN BREKKE | FRIDRIK ÓLAFSSON The Chess Saga of FRIÐRIK ÓLAFSSON with special contributions from Gudmundur G. Thórarinsson, Gunnar Finnlaugsson, Tiger Hillarp Persson, Axel Smith, Ian Rogers, Yasser Seirawan, Jan Timman, Margeir Pétursson and Jóhann Hjartarson NORSK SJAKKFORLAG TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword by President of Iceland, Guðni Th. Jóhannesson ..................4 Preface .........................................................5 Norsk Sjakkforlag Fridrik Ólafsson and his Achievements by Gudmundur G. Thorarinsson .....8 Øystein Brekke Haugesgate 84 A Chapter 1: 1946 – 54 From Childhood to Nordic Champion .............10 3019 Drammen, Norway Mail: [email protected] Chapter 2: 1955 – 57 National Hero and International Master ...........42 Tlf. +47 32 82 10 64 / +47 91 18 91 90 www.sjakkforlag.no Chapter 3: 1958 – 59 A World Championship Candidate at 23 ..........64 www.sjakkbutikken.no Chapter 4: 1960 – 62 Missed Qualification in the 1962 Interzonal ........94 ISBN 978-82-90779-28-8 Chapter 5: 1963 – 68 From Los Angeles to Reykjavik ..................114 Authors: Øystein Brekke & Fridrik Ólafsson Chapter 6: 1969 – 73 The World’s Strongest Amateur Player ............134 Design: Tommy Modøl & Øystein Brekke Proof-reading: Tony Gillam & Hakon Adler Chapter 7: 1974 – 76 Hunting New Tournament Victories ..............166 Front page photo: Chapter 8: 1977 – 82 Brilliant Games & President of FIDE ..............206 Fridrik in the Beverwijk tournament 1961. (Harry Pot, Nationaal Archief) Chapter 9: 1983 – 99 Fridrik and the Golden Era of Icelandic Chess ....246 Production: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Chapter 10: 2000 – An Honorary Veteran Still Attacking ..............262 Cover: XIDE AS & Norsk Sjakkforlag Printing and binding: XIDE AS Games in the Book ................................................282 Paper: Multiart Silk 115 gram Opening index ....................................................284 Copyright © 2021 by Norsk Sjakkforlag / Øystein Brekke Index of opponents, photos and illustrations ...........................285 All rights reserved. -

FIDE Congress Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia General Assembly 29 September – 2 October 2010 MINUTES the Minutes Show the Date That Ea

FIDE Congress Khanty-Mansiysk, Russia General Assembly 29 September – 2 October 2010 MINUTES The minutes show the date that each item on the agenda was taken. Minutes of decisions on September 29 th and 30 th were submitted for approval by delegates on October 1 st . There were some minor amendments and then the General Assembly unanimously approved the minutes. Similarly, minutes of decisions on October 1 st were approved on October 2 nd . There was a roll call at the start of each day by the General Secretary and a quorum established. 0.1. Obituaries. (29 September) We mourn the passing in the preceding year of friends of FIDE among whom we remember: Florencio Campomanes (PHI) – FIDE Honorary President GM Vassily Smyslov (RUS) – former World Champion Boris Khropov (RUS) – former President, St. Petersburg Chess Federation Bill Hook – (BVI) Arthur Kobese (RSA) – former Zone President GM Andor Lilienthal (HUN) IA Feodor Skripchenko (MDA) – former FIDE Zone President (1.8) IA Gertrude Wagner (AUT) – FIDE Honorary Member GM Diez Del Corral Jesus (ESP) IA Hernandez Santana Gregorio (ESP) WGM Elena Tairova (RUS) Ricardo Aguilar – Founder of the Belize Chess Federation IA Vitaly Sevastianov (RUS) – former President of the USSR Chess Federation Yuri Shabanov (RUS) – former World Senior Champion Hussein Nafady (EGY) – President of the Egyptian Chess Federation Craig van Tilbury (BVI) GM Bent Larsen (DEN) Prof. K Jungwirth paid tribute to the work of Florencio Campomanes and the huge beneficial effect that he had on FIDE during his Presidency. 0.2. Report of the Committee tasked to establish the legality of the proxies. -

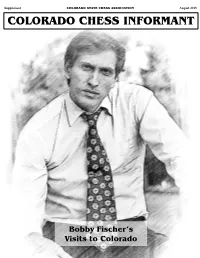

Bobby Fischer's Visits to Colorado – Colorado Chess Informant

Supplement COLORADO STATE CHESS ASSOCIATION August 2018 COLORADO CHESS INFORMANT Bobby Fischer’s Visits to Colorado Supplement Colorado Chess Informant August 2018 COLORADO CHESS HISTORY - BOBBY FISCHER’S VISITS by National Master Todd Bardwick This supplement to the Informant is an attempt to give a detailed historical account of Bobby Fischer’s visits to Colorado for current and future generations. I have written many articles about it in the Rocky Mountain News over the 17 years I wrote for the newspaper. (To find thoses articles, you can go to www.ColoradoMasterChess.com and click on the Articles link.) This became a much bigger project that I originally anticipated as the list of people to talk to grew. It became a real life “Searching for Bobby Fischer”, just 47 years later. My research on the subject started back in the early to mid 1990s while visiting John Howell. John’s contributions to Colorado chess as an organizer where monumental. I realized that the stories he told were of huge historical significance to the history of Colorado chess. Today, I wish my notes of our conversations were even more detailed and, looking back, there is a lot more I would like to ask him. John passed away on March 7, 2000 at the age of 88. Cathy Howell, John’s daughter, recently helped me to fill in some of the blanks, provided a copy of some of the notes from John’s diaries (he kept a detailed diary for most days of his adult life!), and gave me chess articles and photos from his files dating back into the 1960s which are posted on the History Section of the Colorado State Chess Association website. -

16. National Master Bruce Monson Reads Bent Larsen's Memories of the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup

16. National Master Bruce Monson Reads Bent Larsen's Memories of the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup National Master Bruce Monson, born 1967, has long been known as one of the best players in Colorado where he works as a firefighter. The author of a book on the Belgrade Gambit and a contributor to Pasadena 1932, Monson is known as an outstanding chess archivist skilled at finding long lost historical information. He is currently at work on books on the Piatigorsky Cups and Herman Steiner. Here, he reads Bent Larsen’s reminiscences about the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup tournament. Bent Larsen was one of the greatest chess players in the world in the 1960s and 1970s, qualifying for the Candidate Matches four times and reaching the semi-finals on three occasions. His fearless style was perfect for winning tournaments and was particularly successful in the late 1960s which led him to be placed on board 1 for the world ahead of Bobby Fischer in its match with the U.S.S.R. in 1970. Larsen was not only a great player, but also an outstanding writer. His book, Larsen’s Selected Games of Chess: 1948-1969, is recognized as a classic. Bruce Monson: The title of his essay is Oh Yes, I Remember It Well, and he is referring to Maurice Chevalier who sang also with a French accent. So the title, he says, is his and [he writes], “For Jacqueline, I wish you a long life. You have music and chess and that’s already a good beginning.” Oh Yes, I Remember It Well It was my second visit to the United States. -

10. International Master Anthony Saidy Shares Memories of the Steiner Chess Club Recorded: September 12, 2013

10. International Master Anthony Saidy Shares Memories of the Steiner Chess Club Recorded: September 12, 2013 International Master Anthony Saidy played in numerous U.S. Championships and authored the book The Battle of Chess Ideas. He shared his memories of legendary player Bobby Fischer in the 2011 documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World. Here, he reflects upon the legacy of the Piatigorsky Cups and the Steiner Chess Club. John Donaldson: When did you first join the Steiner Chess Club and what is your initial memory of Mrs. Piatigorsky? International Master Anthony Saidy: I came to Los Angeles in the middle of 1962 in order to become a medical intern, and contrary to the conventional wisdom, I didn’t stick to medicine. I had to play some chess, and there was the Steiner Chess Club Championship that year, and for sure, I had to take part in it. My patients had to wait until the game was over, until I got back to the hospital in West L.A. I don’t think I formally joined the club but I played in the Club Championship. JD: And, if I’m not mistaken, you also won the Club Championship? AS: Yes, I did. Undefeated. JD: So, is that the first time you had seen Mrs. Piatigorsky, or you had seen her earlier when you were living in New York, and she had been out there to play in one of the Women’s Championships or some other event? AS: I may have met her at a U.S. Open, but I don’t remember. -

Deep Thought Wins Fredkin Intermediate Prize Hans Berliner

AI Magazine Volume 10 Number 2 (1989) (© AAAI) CHESS REPORT Deep Thought Wins Fredkin Intermediate Prize Hans Berliner ince May 1988, Deep Thought almost all potential contenders. The S (DT), the creation of a team of two first place finishers drew with students at Carnegie Mellon Universi- each other. Hitech led the field at the ty, has been attracting a lot of notice. halfway point but lost to DT in round In the Fredkin Masters Open, May 3 and threw away a winning position 28–30, DT tied for second in a field of against Fidelity in round four (because over 20 masters and ahead of three of a programming bug). The level of other computers, including Hitech play in this tournament was by far the and Chiptest (the winner of the 1987 best ever in a computer event, and the North American Computer Champi- winners clearly deserved their top onships). In August at the U.S. Open, places. DT scored 8.5, 3.5 to tie for eigh- Ten days later, DT achieved the teenth place with Arnold Denker greatest computer success to date. It among others. Its performance was tied for first with GM Tony Miles in marred by hardware and software the prestigious Software Toolworks bugs. However, DT astounded every- Open in Los Angeles with a score of one by beating International Master 6.5, 1.5. Several GMs played in this (IM) Igor Ivanov, the perennial winner tournament, including former World of the U.S. Grand Prix circuit prize, Champion Mikhail Tal of the USSR. who is generally regarded to be as In the tournament, DT became the strong as the average Grandmaster first computer to beat a GM in a regu- (GM). -

The Battle of the Brains

Back to Article Click to Print Monday, Jul. 31, 1972 The Battle of the Brains THE negotiations were going so poorly, Presidential Adviser Henry Kissinger revealed last week, that he felt compelled to intervene "for the good of the country." Kissinger was not referring to his latest secret maneuverings for peace in Viet Nam. He was talking about peace in Reykjavik, Iceland, and the confrontation between Bobby Fischer of the United States and Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union for the world chess championship. After weeks of petty infighting, the stormy encounter of East v. West, of Boris the witty, urbane champion v. Bobby the temperamental, demanding challenger, had grown into an international incident. To avoid a stalemate, Kissinger, a chess player himself, put through a call to Fischer and implored him to play. Fischer agreed, but only with the reluctance of a pouty patriot who says: "If there is one thing I ask for and I don't get, then I don't play." To those who know him best, Bobby was merely being Bobby. "He is," says U.S. Grand Master Larry Evans, "the most individualistic, intransigent, uncommunicative, uncooperative, solitary, self-contained and independent chess master of all time, the loneliest chess champion in the world. He is also the strongest player in the world. In fact, the strongest player who ever lived." Fischer readily agrees with the best-ever claim. For the past decade he has considered himself the "unofficial champion," the maligned and misunderstood victim of a Communist conspiracy to keep him from the world title that is rightfully his. -

Bobby Fischer's

- . -- Drawing by Bob Brandreth UNITED STATES Vn luml' XXIII Number 12 O"C~ m b er , 19611 EDITOR: Burt Hochberg CONTENTS PRESIDENT Marshall Rohland The Larsen Opinion ................. .... ................. ... ... ...... ....... .... ........... ..... 435 VICE·PRESIDENT Isaac Kashdan Chess life, Here and There ........ ... ......... ................ ... ... .... .. .438, 442, 443 SECRETARY Battles on the Danube, by Fra nk Skoff .. .. .. ..... .. .. .. .. .......... ... ......... .. .....· .. 439 Dr. Leroy Dubeck EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Olympiad Final ..... .. ... .. ... ............ ... .. ... .. ... ... ... ........... ............. ... ... ..... .. ... 442 E. B. Edmondson Keres Annotates, by Paul Keres ..... ............ ............... ... .. .............. ....... .. 444 REGIONAL VICE·PRESIDENTS The Negative Sacrifice, by Anthony Sa idy .. .. ...... .. .. .. .. .. ............. .. .. ....... 450 NEW ENGLAND J ames Bolton Thomas C. Barham Benjamin Landey Observation POint, by Mira Radojck ..... .......... ............. ... ........ .... .. .... .. .451 EASTERN Larry Evans on Chess ............... .. ... ... ..... .... ..... ... .... ... .... ......................... 452 MID·ATLANTIC Steve Caruthers Or. Fred A. Sorensen The Openings in the Candidate Matches Po rt Two Lewis Huek s , , by Bernard Zuckerman .............. ..... ... .. .. ... .. .. ... ................... .. ....... 455 SOUTHERN Phlllp Lamb Robert Cole Donald Schultz 12 X 12, by E. B. Edmondson .. ....... ..... ......... .. ... .. .. ... .. ......... ....... .... .. .. .