1. Jacqueline Learns to Play Chess Jump in the Waves Chapter Nine: “From Withholding to Competing” Pages 24 - 25

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2009 U.S. Tournament.Our.Beginnings

Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis Presents the 2009 U.S. Championship Saint Louis, Missouri May 7-17, 2009 History of U.S. Championship “pride and soul of chess,” Paul It has also been a truly national Morphy, was only the fourth true championship. For many years No series of tournaments or chess tournament ever held in the the title tournament was identi- matches enjoys the same rich, world. fied with New York. But it has turbulent history as that of the also been held in towns as small United States Chess Championship. In its first century and a half plus, as South Fallsburg, New York, It is in many ways unique – and, up the United States Championship Mentor, Ohio, and Greenville, to recently, unappreciated. has provided all kinds of entertain- Pennsylvania. ment. It has introduced new In Europe and elsewhere, the idea heroes exactly one hundred years Fans have witnessed of choosing a national champion apart in Paul Morphy (1857) and championship play in Boston, and came slowly. The first Russian Bobby Fischer (1957) and honored Las Vegas, Baltimore and Los championship tournament, for remarkable veterans such as Angeles, Lexington, Kentucky, example, was held in 1889. The Sammy Reshevsky in his late 60s. and El Paso, Texas. The title has Germans did not get around to There have been stunning upsets been decided in sites as varied naming a champion until 1879. (Arnold Denker in 1944 and John as the Sazerac Coffee House in The first official Hungarian champi- Grefe in 1973) and marvelous 1845 to the Cincinnati Literary onship occurred in 1906, and the achievements (Fischer’s winning Club, the Automobile Club of first Dutch, three years later. -

From Los Angeles to Reykjavik

FROM LOS ANGELES CHAPTER 5: TO REYKJAVIK 1963 – 68 In July 1963 Fridrik Ólafsson seized a against Reshevsky in round 10 Fridrik ticipation in a top tournament abroad, Fridrik spent most of the nice opportunity to take part in the admits that he “played some excellent which occured January 1969 in the “First Piatigorsky Cup” tournament in games in this tournament”. Dutch village Wijk aan Zee. five years from 1963 to Los Angeles, a world class event and 1968 in his home town the strongest one in the United States For his 1976 book Fridrik picked only Meanwhile from 1964 the new bian- Reykjavik, with law studies since New York 1927. The new World this one game from the Los Angeles nual Reykjavik chess international gave Champion Tigran Petrosian was a main tournament. We add a few more from valuable playing practice to both their and his family as the main attraction, and all the other seven this special event. For his birthday own chess hero and to the second best priorities. In 1964 his grandmasters had also participated at greetings to Fridrik in “Skák” 2005 Jan home players, plus provided contin- countrymen fortunately the Candidates tournament level. They Timman showed the game against Pal ued attention to chess when Fridrik Benkö from round 6. We will also have Ólafsson competed on home ground started the new biannual gathered in the exclusive Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles for a complete a look at some critical games which against some famous foreign players. international tournament double round event of 14 rounds. -

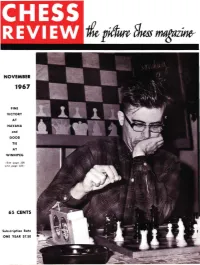

CR1967 11.Pdf

NOVEMBER 1967 FINE VICTORY AT HAVANA and GOOD TIE AT WINNIPEG ( Set PllO" ) 2$ .:ond pig" 323) 65 CENTS Subscription Rat. ONE YEAR 57.50 e wn 789 7 'h by 9 Inches. clothbound 221 diagrams 493 idea Yariations 1704 practical yariations 463 supplementary variations 3894 notes to all yariations and 439 COMPLETE GAMES! BY I. A . HOROWITZ in collaboration with Former World Champion, Dr. Max Euwe. Ernest Gruenfeld, Hans Kmoch. and many other noted authorities This latest Hild immense work, the most exhaustive of its kind, ex· plains in encyclopedic detail the fine points of all openings. It carries the reader well into the middle game, evaluates the prospects there and often gives complete exemplary games so that he is not left hanging in mid.position with the query: What happens now? A logical sequence binds the continuity in each opening. First come the moves with footnotes leading to the key positi on. Then fol· BIBLIOPHILES! low pertinent observations, illustrated by " Idea Variations." Finally, Glossy paper, handsome print, Practical and Supplementary Va riations, well annotated, exemplify the spaciolls paging and all the effective po::isibilities. Each line is appraised: +. - or =. The hi rge format- 71f2 x 9 inches-is designed for ease of read· other appurtenances of exqllis ing and playing. It eliminates much tiresome shuIIling of pages ite book-making combine to between the principal Jines and the respective comments. Clear, make this the handsomest of legible type, a wide margin for inserting notes and variation-identify. ing diagrams are olher plus features. chess books! In addition to all else. -

Kashdan Wins 48Th U.S. Open!

USCF Volume II Friday, Number 1 O!fj cietl Publication of me United States (bess federati on · September 5, 1947 Kashdan Wins 48th U.S. Open! • SANTASIERE, YANOFSKY TIE; COUNT 2S ENTRIES CUELLAW (COLOMBIA) FOURTH IN NYSC TOURNEY ADVANCE NOTICE Fifth Place in Close Contest Shared A press release on the New York State Chess Association Toul"Ila· By Kramer, Shaw, Sanchez, Whitaker ment at Endicott, well In advance ot fi nal registration date, Indicates By virtue of a clear margin of 10 po ints with no losses and advance registration of twenty·fi ve three draws, Isaac Kashdan r egained the title of U. S. Open players trom diUerent parts of tbe Chess Champion, which he shared w ith Horowitz in 1938 at State. "When pairing begins at the Boston . P laying tireless and unerring chess, Kashdan was l.B.M. Country Club, scene of the never behind, and with the ninth round forged into a lead which touranment. the title-holder An was never thereafter overtaken. In the fifth round he drew w ith thony K Santasiere, fresh from a second place tie at the U. S. Open the y outhful George Kramer, in the ninth he drew Santasicre Tournament at Corpus Ch.rlsti, will while K ramer was losing Steinmeyer to take the "lead, and in face George Kramer. 1945 State the t welfth round he drew with Miguel Cuellar of Colombia. Champion who placed In at tie for Tied for secdnd pl ace were former Open Champion Santas fi fth at Corpus Christi. and Dr. Ed ie r ~and Canadian Champion Yanofsky with 10-3 each. -

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels

OCTOBER 25, 2013 – JULY 13, 2014 Object Labels 1. Faux-gem Encrusted Cloisonné Enamel “Muslim Pattern” Chess Set Early to mid 20th century Enamel, metal, and glass Collection of the Family of Jacqueline Piatigorsky Though best known as a cellist, Jacqueline’s husband Gregor also earned attention for the beautiful collection of chess sets that he displayed at the Piatigorskys’ Los Angeles, California, home. The collection featured gorgeous sets from many of the locations where he traveled while performing as a musician. This beautiful set from the Piatigorskys’ collection features cloisonné decoration. Cloisonné is a technique of decorating metalwork in which metal bands are shaped into compartments which are then filled with enamel, and decorated with gems or glass. These green and red pieces are adorned with geometric and floral motifs. 2. Robert Cantwell “In Chess Piatigorsky Is Tops.” Sports Illustrated 25, No. 10 September 5, 1966 Magazine Published after the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, this article celebrates the immense organizational efforts undertaken by Jacqueline Piatigorsky in supporting the competition and American chess. Robert Cantwell, the author of the piece, also details her lifelong passion for chess, which began with her learning the game from a nurse during her childhood. In the photograph accompanying the story, Jacqueline poses with the chess set collection that her husband Gregor Piatigorsky, a famous cellist, formed during his travels. 3. Introduction for Los Angeles Times 1966 Woman of the Year Award December 20, 1966 Manuscript For her efforts in organizing the 1966 Piatigorsky Cup, one of the strongest chess tournaments ever held on American soil, the Los Angeles Times awarded Jacqueline Piatigorsky their “Woman of the Year” award. -

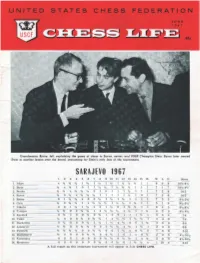

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~. -

Samuel Reshevsky – Lombardy U.S

(21) Samuel Reshevsky – Lombardy U.S. Championship New York, December 1957 King’s Indian Defense [E99] By this time, in the final and deciding round for the U.S. Championship, Bobby had retained a half-point lead (over Sammy). He was paired with the black pieces against Abe Turner. He had the better of the pairing. Yet Abe was a strong master and with white could be quite dangerous. And Bobby was only thirteen. He had some psychological disadvantage against his hefty opponent. Abe was an excellent speed player and always played for stakes, but not against the child Bobby, whom in practice he had beaten many games. Word was that both were content with a draw. Bobby was unwilling to risk a loss, altogether forfeiting his grip on sharing first. And on the other hand, Abe was openly unwilling to spoil the kid’s tournament! Reshevsky had the worse pairing. I am sure that in his mind, considering he had the white pieces, he expected to win. I had lost a game to him in our match the previous year, my only loss to him so far. But I had drawn eight other games with the former prodigy. Two of these came in the 1955 Rosenwald Tournament and five others in the match. Moreover, it had only been four months since my return from the World Junior, so he certainly had to consider me with some caution. Sammy figured the Turner game would end in a draw, and so it did well before the real conflict began in his game with me. -

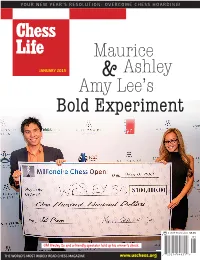

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING!

Bold Experiment YOUR NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTION: OVERCOME CHESS HOARDING! Maurice JANUARY 2015 & Ashley Amy Lee’s Bold Experiment FineLine Technologies JN Index 80% 1.5 BWR PU JANUARY A USCF Publication $5.95 01 GM Wesley So and a friendly spectator hold up his winner’s check. 7 25274 64631 9 IFC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:28 AM Page 1 SLCC_Layout 1 12/10/2014 11:50 AM Page 1 The Chess Club and Scholastic Center of Saint Louis is preparing for another fantastic year! 2015 U.S. Championship 2015 U.S. Women’s Championship 2015 U.S. Junior Closed $10K Saint Louis Open GM/IM Title Norm Invitational 2015 Sinquefi eld Cup $10K Thanksgiving Open www.saintlouischessclub.org 4657 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 | (314) 361–CHESS (2437) | [email protected] NON-DISCRIMINATION POLICY: The CCSCSL admits students of any race, color, nationality, or ethnic origin. THE UNEXPECTED COLLISION OF CHESS AND HIP HOP CULTURE 2&72%(5r$35,/2015 4652 Maryland Avenue, Saint Louis, MO 63108 (314) 367-WCHF (9243) | worldchesshof.org Photo © Patrick Lanham Financial assistance for this project With support from the has been provided by the Missouri Regional Arts Commission Arts Council, a state agency. CL_01-2014_masthead_JP_r1_chess life 12/10/2014 10:30 AM Page 2 Chess Life EDITORIAL STAFF Chess Life Editor and Daniel Lucas [email protected] Director of Publications Chess Life Online Editor Jennifer Shahade [email protected] Chess Life for Kids Editor Glenn Petersen [email protected] Senior Art Director Frankie Butler [email protected] Editorial Assistant/Copy Editor Alan Kantor [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jo Anne Fatherly [email protected] Editorial Assistant Jennifer Pearson [email protected] Technical Editor Ron Burnett TLA/Advertising Joan DuBois [email protected] USCF STAFF Executive Director Jean Hoffman ext. -

Solingen (Unregular)

Solingen (unregular) International tournaments 1968 (100th anniversary tournament of the Solingen Chess Club) Lengyel clear first, ahead of 2. Parma, 3.-7. Pachman, Szabo, Damjanovic, Janosevic (16 players, including O’Kelly, Donner, Medina, Tatai, Lehmann, and Wade who wrote a tournament book; IM Gerusel shared 8th place). This was maybe Levente Lengyel’s (GM in 1964) finest tournament win, he also won at Rome 1964 (joint with Lehmann), Bari 1972 outright, and Reggio Emilia 1972/73 (joint with Popov and Torre). MATHIAS GERUSEL (born Feb-05-1938) Germany Mathias Gerusel is a (West) German IM who finished second to William James Lombardy at the World Junior Championship (1967). He went on to study mathematics. His best tournament results have been 3rd at Büsum 1969 after Bent Larsen and Lev Polugaevsky, and 5th= at Solingen 1974. 1974 Polugaevsky, Kavalek, ahead of 3.-4. Spassky, Kurajica, (15 players, Pachman boycotted), IM Gerusel shared 5th place together with Szabo, Liberzon, and Westerinen, above 9. Uhlmann; including also Heinz Lehmann, and Hajo Hecht) ttp://www.teleschach.de/historie/solingen1974.htm (Standings) http://www.zeit.de/1974/30/der-ausdruck-des-bedauerns (Boycott of Pachman) 1986 (international club championship) Hübner clear first, ahead of 2./3. IM Ralf Lau, Short (Lau beat Short in their direct game) 4. Kavalek, 5.-6 Spassky, IM Lucas Brunner, 7.-8. Sunye-Neto, Westerinen (12 players, among them German IM Capelan who played already in 1968 and in 1974). Note: Brunner vs. Schneider (https://www.365chess.com/game.php?gid=2169447) has a wrong score, Brunner won Ralf Lau achieved his third an final GM norm to become a grandmaster. -

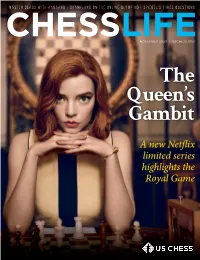

The Queen's Gambit

Master Class with Aagaard | Shankland on the Online Olympiad | Spiegel’s Three Questions NOVEMBER 2020 | USCHESS.ORG The Queen’s Gambit A new Netflix limited series highlights the Royal Game The United States’ Largest Chess Specialty Retailer 888.51.CHESS (512.4377) www.USCFSales.com EXCHANGE OR NOT UNIVERSAL CHESS TRAINING by Eduardas Rozentalis by Wojciech Moranda B0086TH - $33.95 B0085TH - $39.95 The author of this book has turned his attention towards the best Are you struggling with your chess development? While tool for chess improvement: test your current knowledge! Our dedicating hours and hours on improving your craft, your rating author has provided the most important key elements to practice simply does not want to move upwards. No worries ‒ this book one of the most difficult decisions: exchange or not! With most is a game changer! The author has identified the key skills that competitive games nowadays being played to a finish in a single will enhance the progress of just about any player rated between session, this knowledge may prove invaluable over the board. His 1600 and 2500. Becoming a strong chess thinker is namely brand new coverage is the best tool for anyone looking to improve not only reserved exclusively for elite players, but actually his insights or can be used as perfect teaching material. constitutes the cornerstone of chess training. THE LENINGRAD DUTCH PETROSIAN YEAR BY YEAR - VOLUME 1 (1942-1962) by Vladimir Malaniuk & Petr Marusenko by Tibor Karolyi & Tigran Gyozalyan B0105EU - $33.95 B0033ER - $34.95 GM Vladimir Malaniuk has been the main driving force behind International Master Tibor Karolyi and FIDE Master Tigran the Leningrad Variation for decades. -

YEARBOOK the Information in This Yearbook Is Substantially Correct and Current As of December 31, 2020

OUR HERITAGE 2020 US CHESS YEARBOOK The information in this yearbook is substantially correct and current as of December 31, 2020. For further information check the US Chess website www.uschess.org. To notify US Chess of corrections or updates, please e-mail [email protected]. U.S. CHAMPIONS 2002 Larry Christiansen • 2003 Alexander Shabalov • 2005 Hakaru WESTERN OPEN BECAME THE U.S. OPEN Nakamura • 2006 Alexander Onischuk • 2007 Alexander Shabalov • 1845-57 Charles Stanley • 1857-71 Paul Morphy • 1871-90 George H. 1939 Reuben Fine • 1940 Reuben Fine • 1941 Reuben Fine • 1942 2008 Yury Shulman • 2009 Hikaru Nakamura • 2010 Gata Kamsky • Mackenzie • 1890-91 Jackson Showalter • 1891-94 Samuel Lipchutz • Herman Steiner, Dan Yanofsky • 1943 I.A. Horowitz • 1944 Samuel 2011 Gata Kamsky • 2012 Hikaru Nakamura • 2013 Gata Kamsky • 2014 1894 Jackson Showalter • 1894-95 Albert Hodges • 1895-97 Jackson Reshevsky • 1945 Anthony Santasiere • 1946 Herman Steiner • 1947 Gata Kamsky • 2015 Hikaru Nakamura • 2016 Fabiano Caruana • 2017 Showalter • 1897-06 Harry Nelson Pillsbury • 1906-09 Jackson Isaac Kashdan • 1948 Weaver W. Adams • 1949 Albert Sandrin Jr. • 1950 Wesley So • 2018 Samuel Shankland • 2019 Hikaru Nakamura Showalter • 1909-36 Frank J. Marshall • 1936 Samuel Reshevsky • Arthur Bisguier • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1953 Donald 1938 Samuel Reshevsky • 1940 Samuel Reshevsky • 1942 Samuel 2020 Wesley So Byrne • 1954 Larry Evans, Arturo Pomar • 1955 Nicolas Rossolimo • Reshevsky • 1944 Arnold Denker • 1946 Samuel Reshevsky • 1948 ONLINE: COVID-19 • OCTOBER 2020 1956 Arthur Bisguier, James Sherwin • 1957 • Robert Fischer, Arthur Herman Steiner • 1951 Larry Evans • 1952 Larry Evans • 1954 Arthur Bisguier • 1958 E. -

Chess-Moves-July-Aug

July / August 2006 NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH CHESS FEDERATION £1.50 Magnificent Bequest to the British Chess Federation John Robinson the well known and much esteemed chess organiser and arbiter died on 1st February 2006. John dedicated much of his life to chess in many forms, now comes the news of a magnificent bequest to the British Chess Federation of the order of £650,000. Of this sum about £120,000 will be invested in the British Chess Federation Permanent Invested Fund enabling John’s expressed wish of support for the British Championship to be carried out, the remainder of the bequest will be invested in the John Robinson Youth Chess Trust a Charitable Trust which means no inheritance tax is payable on John’s bequest. It is proposed that this money should be invested in such a way that the capital may be retained and the accumulated income used for grants from the Trust. This Legacy provides stability for the future of the Championship and for Junior Chess. If anyone wishes to consider a bequest to ECF/BCF please contact the Office for further details. Editorial The establishment of the National Chess Library is progressing well. The rooms have now been cleared and the specialised ECF News shelving is in place. The books are in the process of being unpacked with book plates Nominations for being added. As soon as an opening date is fixed this will be announced. There are many Election at the ECF AGM other exciting projects, other than books The voluntary posts to be elected at being discussed with Hastings University, 0YD no later than 13.30 on Wednesday it is amazing how one venture can lead to the AGM on 1 October 006 are: 13 September 2006.