Mucea, B. N. (2018A)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

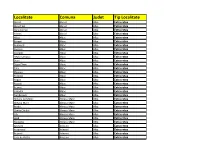

Nr. Crt. JUDET DENUMIRE UAT 1 AIUD 2 ALBA IULIA 3 ALBAC 4

VI. UAT-uri care au semnat contracte de servicii în exercițiul financiar 2017, 15 noiembrie 17 Nr. crt. JUDET DENUMIRE UAT 1 AIUD 2 ALBA IULIA 3 ALBAC 4 ALMASU MARE 5 BAIA DE ARIES 6 BERGHIN 7 BISTRA 8 BLAJ 9 BUCERDEA GRANOASA 10 BUCIUM 11 CALNIC 12 CENADE 13 CERGAU 14 CERU-BACAINTI 15 CETATEA DE BALTA 16 CIURULEASA 17 CRACIUNELU DE JOS 18 CRICAU 19 CUGIR 20 CUT 21 DOSTAT 22 GALDA DE JOS 23 GIRBOVA 24 HOPIRTA 25 JIDVEI 26 ALBA LOPADEA NOUA 27 LUNCA MURESULUI 28 METES 29 MIHALT 30 MIRASLAU 31 MOGOS 32 NOSLAC 33 OCNA MURES 34 PIANU 35 PONOR 36 RADESTI 37 RIMET 38 RIMETEA 39 ROSIA DE SECAS 40 SALISTEA 41 SASCIORI 1 ALBA 42 SEBES 43 SIBOT 44 SINCEL 45 SONA 46 STREMT 47 TEIUS 48 UNIREA 49 VALEA LUNGA 50 VIDRA 51 ZLATNA 52 ALMAS 53 APATEU 54 ARCHIS 55 BELIU 56 BIRCHIS 57 BIRZAVA 58 BOCSIG 59 BRAZII 60 BUTENI 61 CARAND 62 CERMEI 63 CHISINDIA 64 CHISINEU-CRIS 65 CONOP 66 CRAIVA 67 CURTICI 68 DEZNA 69 DIECI 70 DOROBANTI 71 FELNAC 72 GRANICERI 73 GURAHONT 74 HASMAS 75 IGNESTI 76 INEU 77 IRATOSU 78 LIPOVA 79 MACEA 80 MISCA 81 MONEASA 82 NADLAC 83 OLARI ARAD 84 PAULIS 85 PECICA 86 PEREGU MARE 2 ARAD 87 PETRIS 88 PILU 89 PINCOTA 90 PLESCUTA 91 SANTANA 92 SAVIRSIN 93 SEBIS 94 SEITIN 95 SELEUS 96 SEMLAC 97 SEPREUS 98 SICULA 99 SILINDIA 100 SIMAND 101 SINTEA MARE 102 SISTAROVAT 103 SOCODOR 104 SOFRONEA 105 TAUT 106 TIRNOVA 107 USUSAU 108 VARADIA DE MURES 109 VINGA 110 VIRFURILE 111 ZABRANI 112 ZADARENI 113 ZARAND 114 ZERIND 115 ZIMANDU NOU 116 BALILESTI 117 BASCOV 118 BIRLA 119 BOTESTI 120 BRADU 121 BUDEASA 122 BUZOESTI 123 CETATENI 124 CORBI 125 GODENI -

The Socio-Occupational Structure of the Population in the Apuseni Mountains

ROMANIAN REVIEW OF REGIONAL STUDIES, Volume XI, Number 2, 2015 THE SOCIO-OCCUPATIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE POPULATION IN THE APUSENI MOUNTAINS. CASE STUDY: THE LAND OF THE MOȚI GABRIELA-ALINA MUREŞAN1, CRISTIAN-NICOLAE BOŢAN2 ABSTRACT – The aim of our study is to highlight the changes in the socio-occupational structure of the population living in the Apuseni Mountains between 1992 and 2011, through a case study example, namely the Land of the the Moţi, a region in the central part of the mountains. The aim is to highlight any critical status induced by the geodemographic components. These changes do not differ significantly from other regions in Romania and they are expressed by a decreasing share of the population employed in the secondary sector, in parallel with an increase of the same segment of population employed in primary and tertiary sectors. However, due to changes in the Romanian economy in the last two decades, agriculture and forestry have become dominant in the region. Even if an obvious risk situation is not noticeable, as striking as depopulation or ageing, we must sound the alarm about communities in the mountain area. Despite the obvious intensification of the tertiary activities, this area remains weakly developed, dominated by the agricultural sector, less productive and low yield. Keywords: socio-occupational structure, geodemographic risks, sectors of activity, active population, employed population INTRODUCTION This study, which aims to highlight the changes in the socio-occupational structure of the population living in the Apuseni Mountains for two decades (1992-2011) and to highlight any critical conditions related to it, is a continuation of some previous works on the Apuseni Mountains regional system. -

Alba County: Towards a Balanced Development of the Territory Based on Its Cultural Heritage

Alba county: towards a balanced development of the territory based on its cultural heritage. Marian Aitai To cite this version: Marian Aitai. Alba county: towards a balanced development of the territory based on its cultural heritage.. In International Conference of Territorial Intelligence, Sep 2006, Alba Iulia, Romania. p. 103-110. halshs-00515920 HAL Id: halshs-00515920 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00515920 Submitted on 3 Jun 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PAPERS ON REGION, IDENTITY AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT ALBA COUNTY: TOWARDS A BALANCED DEVELOPMENT OF THE TERRITORY BASED ON ITS CULTURAL HERITAGE Marian AITAI Executive Director [email protected], Tél: 0743098487 Professional address Alba County Council, 1, I.I.C. Bratianu Square – R-ALBA IULIA, Romania. Abstract: The objective of the paper is to make a brief presentation of the cultural potential of the Alba County, as a major opportunity for future development. As the formulation of the development strategy is in progress, only the analysis stage being completed, this paper will provide some personal ideas on the future development policies that need to address the sensitive issue of cultural heritage. -

International Conference of Territorial Intelligence, Alba Iulia 2006. Vol.1

International Conference of Territorial Intelligence, Alba Iulia 2006. Vol.1, Papers on region, identity and sustainable development (deliverable 12 of caENTI, project funded under FP6 research program of the European Union), Aeternitas, Alba Iulia, 2007 Jean-Jacques Girardot, M. Pascaru, Ioan Ileana To cite this version: Jean-Jacques Girardot, M. Pascaru, Ioan Ileana. International Conference of Territorial Intelligence, Alba Iulia 2006. Vol.1, Papers on region, identity and sustainable development (deliverable 12 of caENTI, project funded under FP6 research program of the European Union), Aeternitas, Alba Iulia, 2007. 2007, 280 p. halshs-00531457 HAL Id: halshs-00531457 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00531457 Submitted on 26 Jun 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. International Conference of Territorial Intelligence of Alba Iulia 2006 (CAENTI) | http://www.territorial-intelligence.eu Jean-Jacques GIRARDOT Mihai PASCARU Ioan ILEANĂ Editors International Conference of Territorial Intelligence ALBA IULIA 2006 Volume 1 -

Judet Comuna Localitate Geoid Zone Alba Abrud Abrud 12347 Zona 2

Judet Comuna Localitate geoid Zone Alba Abrud Abrud 12347 zona 2 Alba Abrud Abrud-Sat 12348 zona 2 Alba Abrud Gura Cornei 12349 zona 2 Alba Abrud Soharu 12350 zona 2 Alba Aiud Gambas 12354 zona 2 Alba Aiud Garbova de Sus 12356 zona 2 Alba Aiud Garbovita 12357 zona 2 Alba Aiud Magina 12358 zona 2 Alba Aiud Pagida 12359 zona 1.1 Alba Aiud Sancrai 12360 zona 2 Alba Aiud Tifra 12361 zona 1.1 Alba Albac Albac 12642 zona 2 Alba Albac Barasti 12643 zona 2 Alba Albac Budaiesti 12644 zona 2 Alba Albac Cionesti 12645 zona 2 Alba Albac Costesti 12646 zona 2 Alba Albac Dealu Lamasoi 12647 zona 2 Alba Albac Deve 12648 zona 2 Alba Albac Dupa Plese 12649 zona 2 Alba Albac Fata 12650 zona 2 Alba Albac Plesesti 12651 zona 2 Alba Albac Potionci 12652 zona 2 Alba Albac Rogoz 12653 zona 2 Alba Albac Rosesti 12654 zona 2 Alba Albac Rusesti 12655 zona 2 Alba Albac Sohodol 12656 zona 2 Alba Albac Tamboresti 12657 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareAlmasu de Mijloc12658 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareAlmasu Mare 12659 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareBradet 12660 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareCheile Cibului 12661 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareCib 12662 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareGlod 12663 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareHanes Mina 12664 zona 2 Alba Almasu MareNadastia 12665 zona 2 Alba Arieseni Arieseni 12666 zona 2 Alba Arieseni Avramesti 12667 zona 2 Alba Arieseni Bubesti 12668 zona 2 Alba Arieseni Casa de Piatra 12669 zona 1.1 Alba Arieseni Cobles 12670 zona 2 Alba Arieseni Dealu Bajului 12671 zona 2 Alba Arieseni Fata Cristesei 12672 zona 2 Alba Arieseni Fata Lapusului 12673 zona 1.1 Alba Arieseni Galbena 12674 -

Lista Persoanelor Fizice (P.F.) Autorizate in Judetul Alba

LISTA PERSOANELOR FIZICE (P.F.) AUTORIZATE IN JUDETUL ALBA Ad Adre Adres Adre re Nr. Categ Adresa - Adresa sa - Adresa - Nume, prenume Adresa - Strada a - sa - sa - Adresa - Email Serie autorizatie Crt. orie Localitatea - Nr. Scar Telefon Bloc Etaj Ap a . 1 Agachi Gheorghe A Alba Iulia Strada Milenium 23 0740604421; [email protected] RO- B-F NR. 0991 2 Alexa Ioan B Micesti Strada Zlatnei 62 - - 0747073762 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0090 3 Almasan Andra Ioana B Rosia Montana Strada Principala 330 12 1 2 5 0743382901 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR. 0210 4 Almasan Andra Ioana C Rosia Montana 330 12 1 2 5 0743382901 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0186 5 Ampoitan Ioan B Alba Iulia Strada Revolutiei 1989 18 B8 A 1 8 0766209957 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0070 6 Ampoitan Marius-Ioan B Valeni 25 0788795515 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR. 0215 7 Apolzan Mihai B Sebes Strada Cantarului 26 0742780641 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0025 Strada Bogdan Petriceicu 8 Ardelean Radu B Alba Iulia Hasdeu 9 C3 4 0740609609 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0159 9 Avram Craciunel Madalin C Stei-Arieseni Aleea - 633 0745766272 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0164 10 Avram Iancu B Ciugud 120 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR. 0108 11 Baidac Petre Ioan B Alba Iulia Strada Stefan Cel Mare 3 10 A 17 0753098388 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR. 0160 12 Balan Ovidiu Mihai B Teius Strada Avram Iancu 34 0746110575 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0093 13 Balaneanu Flavius Avram D Alba Iulia Strada Gemina 3 AC20 7 0721207167 [email protected] RO-B -F NR, 0437 Bulevardul Tudor 14 Baldea Radu-Alexandru C Alba Iulia Vladimirescu 50G 0744998439 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0148 15 Bar Ioan C Vârtop 1351 0752641117 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR, 0187 16 Barastean Silviu B Alba Iulia Strada Septimiu Severus 3 TOL3 14 0723133499 [email protected] RO-AB-F NR. -

Geographic Identity Aspects of the Land of the Moti. Cristian Nicolae Botan, Oana-Ramona Ilovan

Geographic identity aspects of the Land of the Moti. Cristian Nicolae Botan, Oana-Ramona Ilovan To cite this version: Cristian Nicolae Botan, Oana-Ramona Ilovan. Geographic identity aspects of the Land of the Moti.. In International Conference of Territorial Intelligence, Sep 2006, Alba Iulia, Romania. p. 87-93. halshs-00516049 HAL Id: halshs-00516049 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00516049 Submitted on 10 Jun 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GEOGRAPHIC IDENTITY ASPECTS OF THE LAND OF THE MOI Cristian Nicolae BoĠan Professor Assistant in Regional Geography [email protected], + 40 740 088 945 Oana-Ramona Ilovan Professor Assistant in Regional Geography [email protected], + 40 742 074 946 Institution address Babeş-Bolyai University, Faculty of Geography, Clinicilor Street 5-7, 400006, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Summary: This paper focuses on analysing all the geographic and historical aspects that were involved into creating the geographic identity of the Land of the Moi, a region in the heart of the Apuseni Mountains. The purpose of the study is that of identifying and establishing the future strategies for the sustainable development of this region while underlining first the strengths and the weaknesses of the territorial system. -

Localitate Comuna Judet Tip Localitate

Localitate Comuna Judet Tip Localitate Abrud Abrud Alba Extra retea Abrud-Sat Abrud Alba Extra retea Gura Cornei Abrud Alba Extra retea Soharu Abrud Alba Extra retea Albac Albac Alba Extra retea Barasti Albac Alba Extra retea Budaiesti Albac Alba Extra retea Cionesti Albac Alba Extra retea Costesti Albac Alba Extra retea Dealu Lamasoi Albac Alba Extra retea Deve Albac Alba Extra retea Dupa Plese Albac Alba Extra retea Fata Albac Alba Extra retea Plesesti Albac Alba Extra retea Potionci Albac Alba Extra retea Rogoz Albac Alba Extra retea Rosesti Albac Alba Extra retea Rusesti Albac Alba Extra retea Sohodol Albac Alba Extra retea Tamboresti Albac Alba Extra retea Almasu de Mijloc Almasu Mare Alba Extra retea Almasu Mare Almasu Mare Alba Extra retea Bradet Almasu Mare Alba Extra retea Cheile Cibului Almasu Mare Alba Extra retea Cib Almasu Mare Alba Extra retea Glod Almasu Mare Alba Extra retea Nadastia Almasu Mare Alba Extra retea Arieseni Arieseni Alba Extra retea Avramesti Arieseni Alba Extra retea Bubesti Arieseni Alba Extra retea Casa de Piatra Arieseni Alba Extra retea Cobles Arieseni Alba Extra retea Dealu Bajului Arieseni Alba Extra retea Fata Cristesei Arieseni Alba Extra retea Fata Lapusului Arieseni Alba Extra retea Galbena Arieseni Alba Extra retea Hodobana Arieseni Alba Extra retea Izlaz Arieseni Alba Extra retea Pantesti Arieseni Alba Extra retea Patrahaitesti Arieseni Alba Extra retea Poienita Arieseni Alba Extra retea Ravicesti Arieseni Alba Extra retea Stei-Arieseni Arieseni Alba Extra retea Sturu Arieseni Alba Extra retea -

Statement of Significance

Statement of Significance Cârnic Massif, Roia Montan, jud Alba Romania Prof Andrew Wilson Prof David Mattingly Michael Dawson FSA MIfA September 2010 with additional summary July 2011 Statement of Significance Roia Montan, Crnic Massif This Statement of Significance has been written by Professor Andrew Wilson, University of Oxford, Institute of Archaeology and Professor David Mattingly, of the University of Leicester, School of Archaeology and Ancient History. The project was managed by Michael Dawson FSA MifA, Director of CgMs Consultancy Ltd. The contents of the report reflect the views of the three authors ©. No part of this report is to be copied in any way without prior written consent. Every effort is made to provide detailed and accurate information, however, the Universities of Oxford, Leicester and CgMs cannot be held responsible for errors or inaccuracies within this report. 2 MD/12092 Statement of Significance Roia Montan, Crnic Massif CONTENTS Preface Executive Summary 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Statement of Significance 3.0 The Significance of Specific Attributes 4.0 The Significance of Historic Processes 5.0 Bibliography 3 MD/12092 Statement of Significance Roia Montan, Crnic Massif LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig 1 Roman Roia Montan Fig 2 The Cetate opencast, seen from the Cârnic Massif Fig 3 Entrances to the ancient mine galleries at Guri Fig 4 The Roman circular mausoleum at Tu Guri, in its temporary cover building Fig 5 The Cârnic massif seen from Roia Montan Fig 6 The modern village of Corna and, in the background from left to right, waste from the Cetate opencast; Cârnicel; and the Cârnic massif. -

Easychair Preprint Description and Analysis of the Main Cause That Led

EasyChair Preprint № 2011 Description and analysis of the main cause that led to the invalidation of the referendum concerning the restart of mining activity at Roşia Montană Bogdan-Nicolae Mucea EasyChair preprints are intended for rapid dissemination of research results and are integrated with the rest of EasyChair. November 20, 2019 Description and Analysis of the Main Causes that Led to the Invalidation of the Referendum Regarding the Restarting of Mining at Roşia Montană MUCEA Bogdan-Nicolae Doctoral School of Sociology, University of Bucharest (ROMANIA) [email protected] Abstract: In order to implement the gold and silver mining project in Roșia Montană, Roșia Montană Gold Corporation (RMGC) adopted the strategy of glocalisation in its interaction with the local community; as part of the same strategy, the referendum to restart mining in the Apuseni region was also conducted. The article presents, based on the data analysis technique, the results of the referendum, while also identifying the main causes of its invalidation. Among the causes referred to below, the disregard of the concentric circles model and the exaggerated extension of the areas (the localities) where the referendum was organized emerge as prominent. The consultation of the population from certain localities in Alba county was organized on the same day with the parliamentary elections of December 9, 2012. Even though the proportion of population who wanted to restart mining was a significant one (62.45%), the referendum was invalidated due to the non-quorum (i.e. the presence of 50% + 1 of the number of citizens registered on the electoral lists). Based on defining the five concentric zones, this paper demonstrateshow increasing distance from Roșia Montană influenced the presence at voting. -

Aiud 1213 Alba Iulia 1017 Albac 2130 Almasu Mare 2309 Berghin 2988

VI. Lucrări în derulare la nivel de sector cadastral (Finanțare 2017-2019) Nr. crt. Județ Denumire UAT-uri în lucru SIRUTA Aiud 1213 Alba Iulia 1017 Albac 2130 Almasu Mare 2309 Berghin 2988 Bistra 3039 Blaj 1348 Bucerdea Granoasa 9026 Bucium 3459 Calnic 4106 Cenade 3761 Cergau 3805 Ceru-Bacainti 3841 Cetatea de Balta 3958 Ciuruleasa 4008 Craciunelu de Jos 4188 Cricau 4142 Cugir 1696 Cut 9019 Dostat 4268 Galda de Jos 4366 Garbova 4482 Hoparta 4703 Jidvei 5103 1 ALBA Lopadea Noua 5210 Lunca Muresului 5309 Metes 5577 Mihalt 5700 Mogos 5826 Noslac 6048 Ocna Mures 1794 Pianu 6217 Ponor 6397 Radesti 6547 Ramet 6627 Rametea 6592 Rosia de Secas 6930 Salistea 7044 Sancel 7348 Sasciori 7099 Sebeş 1874 Sibot 7810 Sona 7865 Stremt 7767 Teius 8096 Unirea 8158 Valea Lunga 8354 Vidra 8425 1 ALBA Zlatna 1936 Almas 9743 Apateu 9798 Archis 9832 Barzava 10104 Beliu 9930 Birchis 10006 Bocsig 10195 Brazii 10239 Buteni 10293 Carand 10346 Cermei 10373 Chisindia 10417 Chisineu-Cris 9459 Conop 10453 Craiva 10532 Curtici 9495 Dezna 10649 Dieci 10701 Dorobanti 12912 Felnac 10827 Graniceri 10916 Gurahont 10943 Hasmas 11236 Ignesti 11307 Ineu 9538 Iratosu 11352 Lipova 9574 Macea 11398 Misca 11423 Moneasa 11478 Nadlac 9627 Olari 11502 2 ARAD Pancota 9654 Paulis 11539 Pecica 11584 Peregu Mare 11637 Petris 11664 Pilu 11735 Plescuta 11762 Santana 12091 Savarsin 11842 Sebis 9690 Seitin 12206 Seleus 11995 Semlac 12037 Sepreus 12224 Sicula 12242 Silindia 12288 Simand 12340 Sintea-Mare 12055 Sistarovat 12402 2 ARAD Socodor 12126 Sofronea 9360 Tarnova 12509 Taut 12457 Ususau -

Siruta Judet Uat (Lau2) 2130 Alba Albac 2309 Alba Almasu

ANEXA…… ZONE CU VALOARE NATURALĂ RIDICATĂ SIRUTA JUDET UAT (LAU2) 2130 ALBA ALBAC 2309 ALBA ALMASU MARE 2381 ALBA ARIESENI 2577 ALBA AVRAM IANCU 2988 ALBA BERGHIN 3039 ALBA BISTRA 3397 ALBA BLANDIANA 9026 ALBA BUCERDEA GRANOASA 3459 ALBA BUCIUM 4106 ALBA CALNIC 3761 ALBA CENADE 3805 ALBA CERGAU 3841 ALBA CERU-BACAINTI 3958 ALBA CETATEA DE BALTA 1071 ALBA CIUGUD 4008 ALBA CIURULEASA 4188 ALBA CRACIUNELU DE JOS 4142 ALBA CRICAU 9019 ALBA CUT 4240 ALBA DAIA ROMANA 4268 ALBA DOSTAT 4302 ALBA FARAU 4366 ALBA GALDA DE JOS 4482 ALBA GARBOVA 4525 ALBA GARDA DE SUS 4703 ALBA HOPARTA 4767 ALBA HOREA 4927 ALBA IGHIU 4981 ALBA INTREGALDE 5103 ALBA JIDVEI 5167 ALBA LIVEZILE 5210 ALBA LOPADEA NOUA 5336 ALBA LUPSA 5577 ALBA METES 5700 ALBA MIHALT 5755 ALBA MIRASLAU 5826 ALBA MOGOS 1213 ALBA MUNICIPIUL AIUD 1017 ALBA MUNICIPIUL ALBA IULIA 1348 ALBA MUNICIPIUL BLAJ 1874 ALBA MUNICIPIUL SEBES 6048 ALBA NOSLAC 6119 ALBA OCOLIS 6164 ALBA OHABA 1151 ALBA ORAS ABRUD 2915 ALBA ORAS BAIA DE ARIES 1455 ALBA ORAS CAMPENI 1696 ALBA ORAS CUGIR 1794 ALBA ORAS OCNA MURES 8096 ALBA ORAS TEIUS 1936 ALBA ORAS ZLATNA 6217 ALBA PIANU 6271 ALBA POIANA VADULUI 6397 ALBA PONOR 6468 ALBA POSAGA 6547 ALBA RADESTI 6627 ALBA RAMET 6592 ALBA RIMETEA 6930 ALBA ROSIA DE SECAS 6761 ALBA ROSIA MONTANA 6976 ALBA SALCIUA 7044 ALBA SALISTEA 7348 ALBA SANCEL 7384 ALBA SANTIMBRU 7099 ALBA SASCIORI 7197 ALBA SCARISOARA 7810 ALBA SIBOT 7446 ALBA SOHODOL 7865 ALBA SONA 7945 ALBA SPRING 7767 ALBA STREMT 8014 ALBA SUGAG 8158 ALBA UNIREA 8229 ALBA VADU MOTILOR 8354 ALBA VALEA LUNGA 8425 ALBA