Informal and Illegal Detention in Spain, Greece, Italy and Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APAIPA National Report France

APAIPA ACTORS OF PROTECTION AND THE APPLICATION OF THE INTERNAL PROTECTION ALTERNATIVE NATIONAL REPORT FRANCE European Refugee Fund of the European Commission 2014 I. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS. ............................................................................................................................ 2 II. GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS. ..................................................................................................................... 2 III. BACKGROUND: THE NATIONAL ASYLUM SYSTEM. .................................................................................. 2 A. APPLICABLE LAW. .......................................................................................................................................... 2 B. INSTITUTIONAL SETUP. .................................................................................................................................... 3 C. THE PROCEDURE. ........................................................................................................................................... 4 D. REPRESENTATION AND LEGAL AID. ..................................................................................................................... 5 IV. METHODOLOGY: SAMPLE AND INTERVIEWS. .......................................................................................... 6 A. METHODOLOGY USED. .................................................................................................................................... 6 B. DESCRIPTION OF THE SAMPLE. ......................................................................................................................... -

Federal Constitution of Malaysia

LAWS OF MALAYSIA REPRINT FEDERAL CONSTITUTION Incorporating all amendments up to 1 January 2006 PUBLISHED BY THE COMMISSIONER OF LAW REVISION, MALAYSIA UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE REVISION OF LAWS ACT 1968 IN COLLABORATION WITH PERCETAKAN NASIONAL MALAYSIA BHD 2006 Laws of Malaysia FEDERAL CONSTITUTION First introduced as the Constitution … 31 August 1957 of the Federation of Malaya on Merdeka Day Subsequently introduced as the … … 16 September 1963 Constitution of Malaysia on Malaysia Day PREVIOUS REPRINTS First Reprint … … … … … 1958 Second Reprint … … … … … 1962 Third Reprint … … … … … 1964 Fourth Reprint … … … … … 1968 Fifth Reprint … … … … … 1970 Sixth Reprint … … … … … 1977 Seventh Reprint … … … … … 1978 Eighth Reprint … … … … … 1982 Ninth Reprint … … … … … 1988 Tenth Reprint … … … … … 1992 Eleventh Reprint … … … … … 1994 Twelfth Reprint … … … … … 1997 Thirteenth Reprint … … … … … 2002 Fourteenth Reprint … … … … … 2003 Fifteenth Reprint … … … … … 2006 Federal Constitution CONTENTS PAGE ARRANGEMENT OF ARTICLES 3–15 CONSTITUTION 17–208 LIST OF AMENDMENTS 209–211 LIST OF ARTICLES AMENDED 212–229 4 Laws of Malaysia FEDERAL CONSTITUTION NOTE: The Notes in small print on unnumbered pages are not part of the authoritative text. They are intended to assist the reader by setting out the chronology of the major amendments to the Federal Constitution and for editorial reasons, are set out in the present format. Federal Constitution 3 LAWS OF MALAYSIA FEDERAL CONSTITUTION ARRANGEMENT OF ARTICLES PART I THE STATES, RELIGION AND LAW OF THE FEDERATION Article 1. Name, States and territories of the Federation 2. Admission of new territories into the Federation 3. Religion of the Federation 4. Supreme Law of the Federation PART II FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES 5. Liberty of the person 6. Slavery and forced labour prohibited 7. -

American Organic Law and Government. Form #11.217

American Organic Law By: Freddy Freeman American Organic Law 1 of 247 Copyright Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry, http://sedm.org Form #11.217, Rev. 12/12/2017 EXHIBIT:___________ Revisions Notes Updates to this release include the following: 1) Added a new section titled “From Colonies to Sovereign States.” 2) Improved the analysis on Declaration of Independence, which now covers the last half of the document. 3) Improved the section titled “Citizens Under the Articles of Confederation” 4) Improved the section titled “Art. I:8:17 – Grant of Power to Exercise Exclusive Legislation.” This new and improved write-up presents proof that the States of the United States Union were created under Article I Section 8 Clause 17 and consist exclusively of territory owned by the United States of America. 5) Improved the section titled “Citizenship in the United States of America Confederacy.” 6) Added the section titled “Constitution versus Statutory citizens of the United States.” 7) Rewrote and renamed the section titled “Erroneous Interpretations of the 14th Amendment Citizens of the United States.” This updated section proves why it is erroneous to interpret the 14th Amendment “citizens of the United States” as being a citizenry which in not domiciled on federal land. 8) Added a new section titled “the States, State Constitutions, and State Governments.” This new section includes a detailed analysis of the 1849 Constitution of the State of California. Much of this analysis applies to all of the State Constitutions. American Organic Law 3 of 247 Copyright Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry, http://sedm.org Form #11.217, Rev. -

AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE N Olbia

SERVIIZIIO SANIITARIIO REGIIONE AUTONOMA DELLA SARDEGNA AZIENDA SANITARIA LOCALE N°2 Olbia GRADUATORIA “ALLEGATO B” ALLA DELIBERAZIONE DEL DIRETTORE GENERALE N°1553 DEL 21.06.2011 N° COGNOME NOME LUOGO DI NASCITA DATA DI NASCITA PUNTEGGIO NOTE 1 SOTGIU ANDREA SASSARI 08/06/1951 8,910 2 LEON SUAREZ ANA VERONICA LAS PALMAS DE GRAN CANARIA 25/11/1970 5,360 3 GIORDANO ORSINI EUGENIO TORRE DEL GRECO 22/12/1982 4,172 4 TOSI ELIANE CURITIBA 20/07/1966 2,906 5 DI PASQUALE LUCA ISERNIA 13/05/1983 2,589 6 BIOSA ANTONIO LA MADDALENA 17/01/1964 2,520 7 BARONE RAFFAELE GELA 29/03/1986 2,460 8 PITZALIS VALERIA CAGLIARI 22/06/1978 2,369 9 GAETANI MARIANNA FOGGIA 13/04/1983 2,320 10 ISU ALESSANDRO SAN GAVINO MONREALE 05/02/1974 2,270 11 SERAFINI VINCENZO ASCOLI PICENO 19/03/1977 2,240 12 TALANA MICHELE IGLESIAS 21/06/1987 1,780 p. per età 13 MELIS MIRKO CAGLIARI 06/11/1986 1,780 14 ABBRUSCATO RICCARDO AGRIGENTO 14/12/1981 1,660 15 PODDA SILVIA ARBUS 10/07/1985 1,642 1 Pubblica selezione - Collaboratore Professionale Sanitario-Tecnico Sanitario di Radiologia Medica – cat. D. 16 LODATO NICOLA CAVA DE' TIRRENI 15/05/1982 1,570 p. per età 17 DE DOMINICIS GIANLUCA ARIANO IRPINO 14/02/1977 1,570 18 DI CAIRANO LUCA PASCAL LUGANO 15/08/1981 1,550 19 LIOCE SABRINA SAN SEVERO 06/10/1987 1,460 20 D'AMICO ALFONSO CAVA DE' TIRRENI 14/03/1981 0,990 21 CALABRO' FRANCESCA CAGLIARI 14/03/1985 0,961 22 CARBONE CARMINE AVELLINO 17/11/1975 0,947 23 RUNZA GIUSEPPE ROSOLINI 03/03/1977 0,920 24 MICILLO ALESSANDRO LATINA 02/04/1986 0,902 25 PLACENINO MIRELLA SAN GIOVANNI ROTONDO 12/04/1987 0,800 26 BIBBO' ANDREA BENEVENTO 15/09/1987 0,710 p. -

VOYAGE to VALLETTA from the ‘Eternal City’ to the ‘Silent City’ Aboard the Variety Voyager 16Th to 24Th May 2016

LAUNCH OFFER - SAVE £300 PER PERSON VOYAGE TO VALLETTA From the ‘Eternal City’ to the ‘Silent City’ aboard the Variety Voyager 16th to 24th May 2016 All special offers are subject to availability. Our current booking conditions apply to all reservations and are available on request. Cover image: View over the Greek Doric Temple, Segesta, Sicily NOBLE CALEDONIA ere is a rare opportunity to visit both Ruins of the Greek temple at Selinunte Sardinia and Sicily, the Mediterranean’s Htwo largest islands combined with time to explore some of Malta’s wonders from the comfort of the private yacht, the Variety Voyager. This is not an itinerary which a large cruise ship could operate but one which is ideal for our 72-passenger vessel. All three islands feature a magnificent array of ancient ruins and attractive towns and villages which we will visit during our guided excursions whilst we have also allowed for ample time to explore independently. With comfortable temperatures and relatively crowd free sites, May is the perfect time to discover these islands and in addition we have the added benefit of excellent local THE ITINERARY Day 1 London to Rome, Italy. ITALY guides along the way and a knowledgeable Fly by scheduled flight. Arrive Q this afternoon and transfer to the onboard guest speaker who will bring to life Isla Maddalena Rome Olbia• • Variety Voyager in Civitavecchia. • •Civitavecchia Enjoy a welcome drink and dinner all we see. SARDINIA as we sail this evening to Sardinia. TYRRHENIAN SEA Cagliari• Day 2 Isla Maddalena & Olbia, Piazza • Armerina Sardinia. In 1789 Napoleon, then Mazara del • Vallo SICILY a young artillery commander was •Gela thwarted in his attempt to take GOZOQ • •Valletta the Maddalena archipelago by MALTA local Sardinian forces and in 1803 Lord Nelson arrived. -

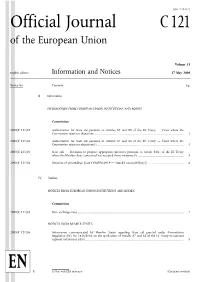

Official Journal C121

ISSN 1725-2423 Official Journal C 121 of the European Union Volume 51 English edition Information and Notices 17 May 2008 Notice No Contents Page II Information INFORMATION FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS AND BODIES Commission 2008/C 121/01 Authorisation for State aid pursuant to Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty — Cases where the Commission raises no objections ............................................................................................. 1 2008/C 121/02 Authorisation for State aid pursuant to Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty — Cases where the Commission raises no objections (1) .......................................................................................... 4 2008/C 121/03 State aids — Decisions to propose appropriate measures pursuant to Article 88(1) of the EC Treaty where the Member State concerned has accepted those measures (1) ................................................ 5 2008/C 121/04 Initiation of proceedings (Case COMP/M.4919 — Statoil/Conocophillips) (1) ..................................... 6 IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS AND BODIES Commission 2008/C 121/05 Euro exchange rates ............................................................................................................... 7 NOTICES FROM MEMBER STATES 2008/C 121/06 Information communicated by Member States regarding State aid granted under Commission Regulation (EC) No 1628/2006 on the application of Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty to national regional investment aid (1) ...................................................................................................... -

Trapani Palermo Agrigento Caltanissetta Messina Enna

4 A Sicilian Journey 22 TRAPANI 54 PALERMO 86 AGRIGENTO 108 CALTANISSETTA 122 MESSINA 158 ENNA 186 CATANIA 224 RAGUSA 246 SIRACUSA 270 Directory 271 Index III PALERMO Panelle 62 Panelle Involtini di spaghettini 64 Spaghetti rolls Maltagliati con l'aggrassatu 68 Maltagliati with aggrassatu sauce Pasta cone le sarde 74 Pasta with sardines Cannoli 76 Cannoli A quarter of the Sicilian population reside in the Opposite page: province of Palermo, along the northwest coast of Palermo's diverse landscape comprises dramatic Sicily. The capital city is Palermo, with over 800,000 coastlines and craggy inhabitants, and other notable townships include mountains, both of which contribute to the abundant Monreale, Cefalù, and Bagheria. It is also home to the range of produce that can Parco Naturale delle Madonie, the regional natural be found in the area. park of the Madonie Mountains, with some of Sicily’s highest peaks. The park is the source of many wonderful food products, such as a cheese called the Madonie Provola, a unique bean called the fasola badda (badda bean), and manna, a natural sweetener that is extracted from ash trees. The diversity from the sea to the mountains and the culture of a unique city, Palermo, contribute to a synthesis of the products and the history, of sweet and savoury, of noble and peasant. The skyline of Palermo is outlined with memories of the Saracen presence. Even though the churches were converted by the conquering Normans, many of the Arab domes and arches remain. Beyond architecture, the table of today is still very much influenced by its early inhabitants. -

Non-Exhaustive Overview of European Government Measures Impacting Undocumented Migrants Taken in the Context of COVID-19

Non-exhaustive overview of European government measures impacting undocumented migrants taken in the context of COVID-19 March-August 2020 This document provides an overview of measures adopted by EU member states and some countries outside the EU in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and foreseen economic downturn, about which PICUM has been informed by its members or has learned of through regular media monitoring.1 Additional information and analysis are provided on regularisation measures taken in Italy and Portugal. Given the limitations of time and capacity, our intention is not to provide an exhaustive presentation, but rather to give a useful summary of measures broadly helpful to people who are undocumented, or who are documented but with insecure status, whatever may have been the authorities’ motivations for their implementation. Please contact [email protected] if you have additional information about any of these measures, or wish to propose a correction. 1 We are grateful to all PICUM members who commented on earlier drafts of this document, and to PICUM trainees Raquel Gomez Lopez and Thomas MacPherson who were instrumental in gathering relevant information and preparing this summary. 1 Contents FOR UNDOCUMENTED MIGRANTS . .3 1. Regularisation �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 1.1. Italy . .3 1.2. Portugal . .6 1.3. Other regularisation measures �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 -

International Standards on Immigration Detention and Non-Custodial Measures

INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION LAW INFORMATION NOTE INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION LAW UNIT NOVEMBER 2011 IML INFORMATION NOTE ON INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS ON IMMIGRATION DETENTION AND NON-CUSTODIAL MEASURES I. Purpose and Scope of the Information Note .................................................................................................. 2 II. General Principles ......................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Definitions: deprivation of liberty vs. restriction of liberty .................................................................................. 2 2. Legality and legitimate grounds for detention ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Necessity, proportionality and prevention from arbitrariness ............................................................................ 3 4. Procedural safeguards .......................................................................................................................................... 3 III. Specific Standards Applicable to Immigration Detention ............................................................................. 4 1. Right to be informed and to communicate with the outside world .................................................................... 4 2. Registration at detention facilities ....................................................................................................................... 4 3. Maximum -

Covid-19 and Immigration Detention

COVID-19 AND IMMIGRATION DETENTION: LESSONS (NOT) LEARNED 1 Page 02 Mapping Covid-19’s impact on immigration detention: why, where, when and what 2 Pages 03-08 Detention policies during the pandemic: unlawful, unclear and unfair 3 Pages 09-10 Alternatives to detention in Covid-19 times: missed opportunity 4 Pages 11-16 Living in detention in time of Covid-19: increased isolation, uncertainties Table ofTable contents and risks ABOUT JRS CREDITS Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is an Drafted by Claudia Bonamini international Catholic organisation with a mission to accompany, serve and Copy-edited by Chiara Leone-Ganado advocate for the rights of refugees and Designed by Pablo Rebaque others who are forcibly displaced. Published on February 2021 Project Learning from Covid-19 Pandemic for a more protective Common European Asylum System. The report Covid-19 and immigration detention: Lessons (not) learned presents the findings and the lessons learned from a mapping on the impact of Covid-19 on administrative detention in seven EU countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, Malta, Romania, Portugal, Spain) This publication has been supported by the European Programme for Integration and Migration (EPIM), a collaborative initiative of the Network of European Foundations (NEF). The sole responsibility for the publication lies with the organiser(s) and the content may not necessarily reflect the positions of EPIM, NEF or EPIM’s Partner Foundation.” MAPPING COVID-19’S IMPACT ON IMMIGRATION DETENTION: WHY, WHERE, WHEN AND WHAT Between the end of February and the beginning of March 2020 it became clear that the Covid-19 outbreak had reached Europe. -

Spectacular Savings

AIR UPGRADE AIR * 99 PREMIUM ECONOMY PREMIUM 99 $ plus FREE - Unlimited Internet Unlimited - FREE plus: t t FREE - Shipboard Credi Shipboard - FREE Package Beverage - FREE Excursions Shore - FREE choose one: choose and for a limited time limited a for and FREE AIRFARE FREE plus * 1 CRUISE FARES CRUISE 1 for 2 SAVINGS SPECTACULAR choose one: FREE - Shore Excursions 2 for 1 CRUISE FARES FREE - Beverage Package * FREE - Shipboard Credit plus FREE AIRFARE plus: FREE - Unlimited Internet CRUISE NAME ORIGINAL NEW LOWER EMBARK & DISEMBARK PORTS OF CALL OLIFE AMENITIES AIR OFFER FARE FARES SHIP | SAIL DATE | DAYS FREE UNLIMITED INTERNET plus (USD) (USD) SOUTH AMERICA (CONTINUED) FREE 5 Shore Excursions Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Recife, Brazil; Alter do Chão (Amazon River), Brazil; Boca da Valeria choose one: Inside $6,499 $5,999 Amazing Amazon (Amazon River), Brazil; Manaus (Amazon River), Brazil; Parintins (Amazon River), Brazil; FREE Beverage Package Rio de Janeiro to Miami Santarém, (Amazon River), Brazil; Devil's Island, French Guiana; Bridgetown, Barbados; $500 Shipboard Credit – Veranda $9,099 $8,599 Insignia | Nov 19, 2016 | 22 Gustavia, St. Barts; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Punta Cana, Dominican Republic; Miami, Florida Penthouse $11,499 $10,999 FREE 5 Shore Excursions Miami, Florida; Gustavia, St. Barts; Castries, St. Lucia; Scarborough, Tobago; choose one: Inside $6,499 $5,999 Rainforests & Rivers Santarém (Amazon River), Brazil; Boca da Valeria (Amazon River), Brazil; Manaus (Amazon River), FREE Beverage Package Miami to Miami Brazil; Parintins -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract.