Do Facebook and Twitter Make You Depressed?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Myth of Portlandia

Portland State University PDXScholar Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Publications Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Winter 2013 The Myth of Portlandia Sara Gates Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/metropolitianstudies Part of the Television Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Gates, S. (2013) The Myth of Portlandia. Winter 2013 Metroscape, p. 24-29. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Institute of Portland Metropolitan Studies Publications by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Myth of Portlandia Portlandia, Grimm, Leverage An interview with Carl Abbott and Karin Magaldi by Sara Gates arl Abbott is a professor of Urban Studies and Planning at Portland State C University and a local expert on the intertwining relationships between the growth, urbanization, and cultural evolutions of cities. Since beginning his tenure at PSU in 1978, Dr. Abbott has published numerous books on Portland itself, as well as the urbanization of the American West; his most recent is Portland in Three Centuries: The Place and the People (2011). Karin Magaldi is the department chair of Theatre & Film at PSU, with extensive experience in teaching screenwriting and production. In addition to directing several PSU departmental productions, she has also worked with local theatre groups including Portland Center Stage, Third Rail Repertory, and Artists Repertory Theatre. Recently, Metroscape writer Sara Gates sat down with Dr. -

Kyle Maclachlan

KYLE MACLACHLAN ACCLAIMED ACTOR KYLE MACLACHLAN has brought indelible charm and a quirky sophistication to some of film and television’s most memorable roles. Since 2005, MacLachlan has channeled his strong interest in the world of wine into a second, equally satisfying professional pursuit. A native of Yaki- ma, Wash., located in the heart of the Columbia Valley wine appellation MacLachlan has produced three highly-rated Columbia Valley wines: Pursued by Bear Cabernet Sauvignon, Baby Bear Syrah and his most recent, Blushing Bear Rosé. What began as an unabashed love for his home state and a desire to stay connected to his family roots has become a true passion and dedication to the craft of winemaking. MacLachlan has be- come an advocate and evangelist for the unique properties and flavor profile of Washington state wines. He is personally involved in every aspect of Pursued by Bear wines. MacLachlan sees a connection between acting and winemaking in terms of the combination and balance of process, patience and creativity. He chose to call his wine Pursued by Bear as an homage to perhaps the most famous of all stage directions, “exit, pursued by bear,” from Act III, scene iii of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. It’s a funny and unexpected phrase that’s not only a nod to his theatrical roots but also plays to his sense of humor. “It just seemed to fit what I was trying to do,” he said. MacLachlan is perhaps best known for his performance as FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper in David Lynch’s ground-breaking series Twin Peaks, for which he received two Emmy nominations and a Golden Globe Award. -

Film Financing

2017 An Outsider’s Glimpse into Filmmaking AN EXPLORATION ON RECENT OREGON FILM & TV PROJECTS BY THEO FRIEDMAN ! ! Page | !1 Contents Tracktown (2016) .......................................................................................................................6 The Benefits of Gusbandry (2016- ) .........................................................................................8 Portlandia (2011- ) .....................................................................................................................9 The Haunting of Sunshine Girl (2010- ) ...................................................................................10 Green Room (2015) & I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore (2017) ...........................11 Network & Experience ............................................................................................................12 Financing .................................................................................................................................12 Filming ....................................................................................................................................13 Distribution ...............................................................................................................................13 In Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................13 Financing Terms .....................................................................................................................15 -

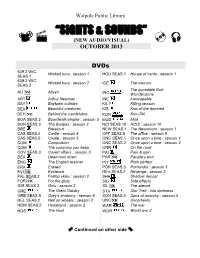

New Audio/Visual) October 2013

Walpole Public Library “SIGHTS & SOUNDS” (NEW AUDIO/VISUAL) OCTOBER 2013 DVDs 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 1 HOU SEAS.1 House of cards : season 1 SEAS.1 639.2 WIC Wicked tuna : season 2 ICE The iceman SEAS.2 The incredible Burt ALI NR Aliyah INC Wonderstone ART Arthur Newman INE Inescapable BAY Baytown outlaws KIL Killing season BEA Beautiful creatures KIS Kiss of the damned BEH NR Behind the candelabra KON Kon-Tiki BOA SEAS.3 Boardwalk empire : season 3 MUD Mud BOR SEAS.3 The Borgias : season 3 NCI SEAS.10 NCIS : season 10 BRE Breakout NEW SEAS.1 The Newsroom : season 1 CAS SEAS.4 Castle : season 4 OFF SEAS.9 The office : season 9 CAS SEAS.5 Castle : season 5 ONC SEAS.1 Once upon a time : season 1 COM Compulsion ONC SEAS.2 Once upon a time : season 2 COM The company you keep ONR On the road COV SEAS.3 Covert affairs : season 3 PAI Pain & gain DEA Dead man down PAR NR Parade’s end ENG The English teacher PIT Pitch perfect ERA Erased POR SEAS.3 Portlandia : season 3 EVI NR Evidence REV SEAS.2 Revenge : season 2 FAL SEAS.2 Falling skies : season 2 SHA Shadow dancer FOR NR For the glory SID Side effects GIR SEAS.2 Girls : season 2 SIL NR The silence GRE The Great Gatsby STA Star Trek : into darkness GRE SEAS.9 Grey’s anatomy : season 9 SON SEAS.5 Sons of anarchy : season 5 HEL SEAS.2 Hell on wheels : season 2 UNC NR Uncertainty HOM SEAS.2 Homeland : season 2 WAR The war HOS The Host WOR World war Z Continued on other side 2 Walpole Public Library NEW AUDIO/VISUAL 2013 Books on CD Manson : the life and Refusal 364.1523 MAN times of -

Toni Und Candace Haben Keinen Laden Mehr

# 2018/10 dschungel https://jungle.world/artikel/2018/10/toni-und-candace-haben-keinen-laden-mehr Die Serie »Portlandia« muss vor linken Kritikern verteidigt werden Toni und Candace haben keinen Laden mehr Von Dierk Saathoff Die Comedyserie »Portlandia« neigt sich ihrem Ende zu, in den USA wird derzeit die finale achte Staffel ausgestrahlt. Die einen finden sie genial, andere aber fühlen sich durch ihren Humor verletzt und vergleichen die Serie gar mit US- Präsident Trumps Ausfällen. »So you want to be entertained / Please go away / Don’t go away.« Diese Zeilen singt Carrie Brownstein, ihres Zeichens Sängerin und Gitarristin der Punkband Sleater-Kinney, in dem passend betitelten Song »Entertain«. Die Ausbeutung der Musiker, grade der Musikerinnen, die Erwartungshaltung des Publikums, von ihnen unterhalten zu werden, die Schwierigkeit der Interpretinnen, genau dem gerecht zu werden und vielleicht doch etwas zu sagen, das den Hörern nicht passt – diese Spannung wird in dem Lied verhandelt. »All you want is entertainment / Rip me open / It’s for free« schreit sie weiter. Unterhaltung als etwas Profanes, Unterhaltung als etwas Vermittelndes, Unterhaltung als Zwang und doch als Freude, Unterhaltung als Notwendigkeit, der man als Musiker nicht entkommt. Es ist kompliziert. Nachdem Sleater-Kinney 2006, ein Jahr nach dem Erscheinen von »Entertain«, eine längere Pause machten, widmete sich Brownstein einem anderen Projekt, das die Frage nach Unterhaltung stellt: dem Fernsehen. Zusammen mit ihrem guten Freund Fred Armisen erfand sie erst die Webserie »Thunder Ant«, die sie dann 2009 dem US- amerikanischen Kabelsender IFC anboten. 2011 startete die erste Staffel unter dem Titel »Portlandia«. »Portlandia« ist eine Sketchserie. -

The Roots Report: an Interview with Aimee Mann

The Roots Report: An Interview with Aimee Mann John Fuzek: Hi, Aimee, how are you? Where are you calling from? Aimee Mann: Good, I am in Los Angeles. JF: Are you currently on tour or home? AM: I am at home for a couple of weeks, we’re going back out on the 19th JF: How long will you be out on the road? AM: This time I think it’s just a few weeks. JF: So, you live in LA? AM: Yes JF: Does being in LA help you get involved with film work as well as music? AM: You know I think there is a thing that living in LA, it helps just being around, there are certain things where you just run into people or seeing someone at a party and they have a project, it’s more likely that they think of you than somebody that they haven’t seen for a long time, I think there’s a weird causal effect that helps JF: Is that how you wound up playing a maid in Portlandia? AM: Yeah, well, I’ve known Fred Armisen for a long time, he lived out here, i knew him from the Largo Comedy scene, there’s a comedy club out here called Cafe Largo and um, before he was on Saturday Night Live, so, yeah, we’ve been friends for a long time, I did meet him out here. JF: Do you have any projects like that coming up or do they just pop up randomly? AM: There’s a new Comedy Central TV show, I don’t think it will be out until next year, called Anton Deville (somewhat inaudible ?) and I have a part, I am in one of those, it’s fun to get calls for that stuff JF: Are you still married to Michael Penn? AM: Yes JF: How come I never really hear about his music anymore? AM: He’s not into performing, it’s not his thing, he does a lot of scoring, he scored The Girls TV show and Masters Of Sex, he likes to be more behind the scenes. -

New York Women in Film & Television (Nywift)

NEW YORK WOMEN IN FILM & TELEVISION (NYWIFT) TO CELEBRATE EXCEPTIONAL WOMEN AT ST TH THE 41 ANNUAL NYWIFT MUSE AWARDS VIRTUALLY ON THURSDAY, DECEMBER 17 , 2020 GOLDEN GLOBE WINNING ACTRESS AWKWAFINA, TWO TIME GOLDEN GLOBE WINNING ACTRESS RACHEL BROSNAHAN, GRAMMY AWARD WINNING ACTRESS RASHIDA JONES, PULITZER PRIZE WINNING NEW YORK TIMES JOURNALISTS JODI KANTOR & MEGAN TWOHEY, PRESIDENT OF ORION PICTURES ALANA MAYO, AWARD-WINNING DIRECTOR GINA PRINCE-BYTHEWOOD, AND TONY AWARD-WINNING ACTRESS ALI STROKER TO RECEIVE HONORS NEW YORK, NY – NOVEMBER 30, 2020 – New York Women in Film & Television (NYWIFT) is proud to present ST the 41 Annual NYWIFT Muse Awards virtual event on Thursday, December 17, 2020. The event will be held virtually beginning at 1:00 PM ET and available for all those who register to watch on online at nywift.org/muse. This year’s theme is “Art & Advocacy,” as NYWIFT recognizes the role of the creative community in advancing positive social change. CBS Sunday Morning contributor, comedian, actress, and self-described “Accidental Pundette” Nancy Giles will again emcee the afternoon’s event, which celebrates women of outstanding vision and achievement both in front of and behind the camera in film, television, the music industry, and digital media. The honorees for this year’s Muse Awards are some of the most extraordinary women in the business: Awkwafina will receive a “Made in New York” Award from the Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment, for her contributions to NYC’s entertainment industry. She is a Golden Globe-winning actress from Queens, New York, who has used her trademark comedic style and signature flair to become a breakout talent. -

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 Dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: the End Of

NETFLIX – CATALOGO USA 20 dicembre 2015 1. 009-1: The End of the Beginning (2013) , 85 imdb 2. 1,000 Times Good Night (2013) , 117 imdb 3. 1000 to 1: The Cory Weissman Story (2014) , 98 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 4. 1001 Grams (2014) , 90 imdb 5. 100 Bloody Acres (2012) , 1hr 30m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 6. 10.0 Earthquake (2014) , 87 imdb 7. 100 Ghost Street: Richard Speck (2012) , 1hr 23m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 8. 100, The - Season 1 (2014) 4.3, 1 Season imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 9. 100, The - Season 2 (2014) , 41 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 10. 101 Dalmatians (1996) 3.6, 1hr 42m imdbClosed Captions: [ 11. 10 Questions for the Dalai Lama (2006) 3.9, 1hr 27m imdbClosed Captions: [ 12. 10 Rules for Sleeping Around (2013) , 1hr 34m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 13. 11 Blocks (2015) , 78 imdb 14. 12/12/12 (2012) 2.4, 1hr 25m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 15. 12 Dates of Christmas (2011) 3.8, 1hr 26m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 16. 12 Horas 2 Minutos (2012) , 70 imdb 17. 12 Segundos (2013) , 85 imdb 18. 13 Assassins (2010) , 2hr 5m imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 19. 13 Going on 30 (2004) 3.5, 1hr 37m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 20. 13 Sins (2014) 3.6, 1hr 32m imdbClosed Captions: [ Available in HD on your TV 21. 14 Blades (2010) , 113 imdbAvailable in HD on your TV 22. -

The Oregonian Opinion: a Building Too Weird for Even Portlandia

The Oregonian Opinion: A building too weird for even Portlandia By David Sarasohn So to all the other dismal aspects of the Portland Building, we can now add a new one: a $95 million estimate for repairs. It’s not hard to imagine why the price is so high. Looking at the building, you’d wonder where in the universe the contractors would get parts. The Portland Building, after all, doesn’t really look like anything else. All huge blue tiles, colored glass and odd pastel flourishes meant to evoke early modern French paintings, it’s always looked like something designed by a Third World dictator’s mistress’s art-student brother, setting off an upheaval in the palace, and possibly a revolution. A few years ago, it comfortably made it onto Travel + Leisure magazine’s list of theugliest buildings in the world, closely following a tourist hotel in North Korea and the Ohio headquarters of a picnic basket company, a building shaped like – yes – a picnic basket. To try to humanize the building, the city affixed to the front of it a huge two-story statue of Portlandia, a figure locals had never known existed – unless personal legal problems had given them lots of occasions to study the city seal – but who quickly became popular, eventually getting her own TV show. Portlandia became so popular, in fact, that Portlanders swiftly began proposing to move her someplace else. (This has been an awkward situation for Portlandia herself. Reportedly, it has taken several interventions by city labor negotiators to keep her from walking off the building.) The Portland Building was a product of what might be called the city’s Paleo Cool stage, the early ‘80s, when Portland was just switching from lumber to lattes, beginning to think it might actually have a unique identity. -

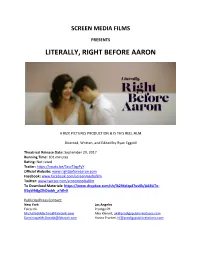

Literally, Right Before Aaron

SCREEN MEDIA FILMS PRESENTS LITERALLY, RIGHT BEFORE AARON A RIZK PICTURES PRODUCTION & IS THIS REEL FILM Directed, Written, and Edited by Ryan Eggold Theatrical Release Date: September 29, 2017 Running Time: 101 minutes Rating: Not rated Trailer: https://youtu.be/5zxz7JqyPyY Official Website: www.rightbeforeaaron.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/screenmediafilm Twitter: www.twitter.com/screenmediafilm To Download Materials: https://www.dropbox.com/sh/lb294xlzpd7uv0k/AABUTe- K5qWhBgZlIiOtubh_a?dl=0 Publicity/Press Contact: New York Los Angeles Falco Ink. Prodigy PR [email protected] Alex Klenert, [email protected] [email protected] Hanna Frankel, [email protected] Produced by Cassandra Kulukundis, Ryan Eggold, Alexandra Rizk Keane, Nancy Leopardi, Ross Kohn Co-Produced by Marcus Cole Associate Produced by Sean Rappleyea Starring Justin Long, Cobie Smulders, Ryan Hansen, John Cho, Kristen Schaal, Dana Delany, Peter Gallagher, Lea Thompson, and Luis Guzmán SYNOPSIS After Adam (Justin Long) gets a call from his ex-girlfriend Allison (Cobie Smulders) telling him she is getting married, Adam realizes he is just not ready to say goodbye. Against the advice of his best friend Mark (John Cho), Adam decides to drive back home to San Francisco to attend the wedding in hopes of convincing himself and everyone else, including her charming fiancé Aaron (Ryan Hansen), that he is truly happy for her. After a series of embarrassing, hilarious, and humbling situations, Adam discovers the comedy in romance, the tragedy of letting go and the hard truth about growing up. RYAN EGGOLD, DIRECTOR STATEMENT The disparity between the fantasy of love and the reality of relationships has always fascinated me. -

Love Is Strange. 04

Love is strange. 04 14. BILL HADER 18. GUEST STAR SIMON RICH 14. EXECUTIVE PRODUCER | CREATOR MICHAEL HOGAN GUEST STAR 19. 14. LORNE MICHAELS VANESSA BAYER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR 20. 07 14. ANDREW SINGER MINKA KELLY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR 20. 15. JONATHAN KRISEL FRED ARMISEN EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GUEST STAR | DIRECTOR 15. 21. RAEANNA GUITARD IAN MAXTONE - GRAHAM GUEST STAR CO - EXECUTIVE PRODUCER | WRITER 08 15. OKSANA BAIUL 21. GUEST STAR ROBERT PADNICK CO - PRODUCER 15. | WRITER MATT LUCAS GUEST STAR 22. DAN MIRK STAFF WRITER 22. SOFIA ALVAREZ 11 STAFF WRITER 22. BEN BERMAN DIRECTOR 23. TIM KIRKBY DIRECTOR 23. HARTLEY GORENSTEIN 12 LINE PRODUCER A SWEET AND SURREAL LOOK AT THE (Unforgettable) as “Liz,” Josh’s intimidating older life-and-death stakes of dating, Man Seeking sister; and Maya Erskine (Betas) as “Maggie,” Woman follows naïve twenty-something “Josh the ex-girlfriend Josh can never quite forget. Greenberg” (Jay Baruchel, How to Train Your Man Seeking Woman is based on Simon Rich’s Dragon) on his unrelenting quest for love. Josh book of short stories, The Last Girlfriend on soldiers through one-night stands, painful break- Earth. Rich created the 10-episode scripted ups, a blind date with a troll, time travel, sex comedy and also serves as Executive Producer/ aliens, many deaths and a Japanese penis Showrunner. Jonathan Krisel, Andrew Singer monster named “Tanaka” on his fantastical and Lorne Michaels, and Broadway Video also journey to find love. serve as Executive Producers. Man Seeking Starring alongside Baruchel are Eric Andre Woman is produced by FX Productions. -

Portlandia S2 Quotes

WHAT THE CRITICS ARE SAYING ABOUT SEASON 2… On the Entertainment Weekly Must List- Entertainment Weekly, January 13, 2012 “hilariously offbeat”- Entertainment Weekly “astute comedy”- Entertainment Weekly “amazing”- Splitsider.com “[a show] you shouldn’t miss” –The Hollywood Reporter "strange and beautiful" – LA Times "audiences loved it”- New York Times Magazine “smartest sketch comedy show on TV”- Salon "Portlandia” is a state of mind."- Salon “…the rare sketch-comedy series that has a sustained object of satire.” – New Yorker “Portlandia is an extended joke about what Freud called the narcissism of small differences: the need to distinguish oneself by minute shadings and to insist, with outsized militancy, on the importance of those shadings.” – New Yorker “both a love letter and a laugh letter to the quirky city of Portland, Ore.” – Entertainment Weekly “Portlandia is everywhere!”– EW.com “Watercooler status” – EW.com “If you haven’t been to “Portlandia,” go now…one [sic] 2011’s best comedies returns” – ABCNews.com “quirky, funny show…” – MSBNC “trippy fun.” – TV Guide “an original comic tone” – Rolling Stone “brilliant” – Rolling Stone “affectionately vicious” – Rolling Stone "winning comedy" –Huffington Post "Spot on"–Huffington Post "On a map of the Internet, the capital these days would be "Portlandia." – NY Daily News "fun"- Washington Post “howlingly funny”- Boston Globe “…smart, earnest satire.” – Seattle Times “obsessive, loving tribute” – Seattle Times "quirky"- Boston Herald "glorious, inventive, smart, incisive"- Newsday