Ast 228 - 4/13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.5 Dimensional Radiative Transfer Modeling of Proto-Planetary Nebula Dust Shells with 2-DUST

PLANETARY NEBULAE: THEIR EVOLUTION AND ROLE IN THE UNIVERSE fA U Symposium, Vol. 209, 2003 S. Kwok, M. Dopita, and R. Sutherland, eds. 2.5 Dimensional Radiative Transfer Modeling of Proto-Planetary Nebula Dust Shells with 2-DUST Toshiya Ueta & Margaret Meixner Department of Astronomy, MC-221 , University of fllinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801, USA ueta@astro. uiuc.edu, [email protected]. edu Abstract. Our observing campaign of proto-planetary nebula (PPN) dust shells has shown that the structure formation in planetary nebu- lae (PNs) begins as early as the late asymptotic. giant branch (AGB) phase due to intrinsically axisymmetric superwind. We describe our latest numerical efforts with a multi-dimensional dust radiative transfer code, 2-DUST, in order to explain the apparent dichotomy of the PPN mor- phology at the mid-IR and optical, which originates most likely from the optical depth of the shell combined with the effect of inclination angle. 1. Axisymmetric PPN Shells and Single Density Distribution Model Since the PPN phase predates the period of final PN shaping due to interactions of the stellar winds, we can investigate the origin of the PN structure formation by observationally establishing the material distribution in the PPN shells, in which pristine fossil records of AGB mass loss histories are preserved in their benign circumstellar environment. Our mid-IR and optical imaging surveys of PPN candidates in the past several years (Meixner at al. 1999; Ueta et al. 2000) have revealed that (1) PPN shells are intrinsically axisymmetric most likely due to equatorially-enhanced superwind mass loss at the end of the AGB phase and (2) varying degrees of equatorial enhancement in superwind would result in different optical depths of the PPN shell, thereby heavily influencing the mid-IR and optical morphologies. -

The Variable Stars and Blue Horizontal Branch of the Metal-Rich Globular Cluster NGC 6441

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server The Variable Stars and Blue Horizontal Branch of the Metal-Rich Globular Cluster NGC 6441 Andrew C. Layden1;2 Physics & Astronomy Dept., Bowling Green State Univ., Bowling Green, OH 43403, U.S.A. Laura A. Ritter Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1090, U.S.A. Douglas L. Welch1,TracyM.A.Webb1 Department of Physics & Astronomy, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4M1, Canada ABSTRACT We present time-series VI photometry of the metal-rich ([Fe=H]= 0:53) globular − cluster NGC 6441. Our color-magnitude diagram shows that the extended blue horizontal branch seen in Hubble Space Telescope data exists in the outermost reaches of the cluster. About 17% of the horizontal branch stars lie blueward and brightward of the red clump. The red clump itself slopes nearly parallel to the reddening vector. A component of this slope is due to differential reddening, but part is intrinsic. The blue horizontal branch stars are more centrally concentrated than the red clump stars, suggesting mass segregation and a possible binary origin for the blue horizontal branch stars. We have discovered 50 new variable stars near NGC 6441, among ∼ them eight or more RR Lyrae stars which are highly-probable cluster members. Comprehensive period searches over the range 0.2–1.0 days yielded unusually long periods (0.5–0.9 days) for the fundamental pulsators compared with field RR Lyrae of the same metallicity. Three similar long-period RR Lyrae are known in other metal-rich globulars. -

Planetary Nebulae Jacob Arnold AY230, Fall 2008

Jacob Arnold Planetary Nebulae Jacob Arnold AY230, Fall 2008 1 PNe Formation Low mass stars (less than 8 M) will travel through the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) of the familiar HR-diagram. During this stage of evolution, energy generation is primarily relegated to a shell of helium just outside of the carbon-oxygen core. This thin shell of fusing He cannot expand against the outer layer of the star, and rapidly heats up while also quickly exhausting its reserves and transferring its head outwards. When the He is depleted, Hydrogen burning begins in a shell just a little farther out. Over time, helium builds up again, and very abruptly begins burning, leading to a shell-helium-flash (thermal pulse). During the thermal-pulse AGB phase, this process repeats itself, leading to mass loss at the extended outer envelope of the star. The pulsations extend the outer layers of the star, causing the temperature to drop below the condensation temperature for grain formation (Zijlstra 2006). Grains are driven off the star by radiation pressure, bringing gas with them through collisions. The mass loss from pulsating AGB stars is oftentimes referred to as a wind. For AGB stars, the surface gravity of the star is quite low, and wind speeds of ~10 km/s are more than sufficient to drive off mass. At some point, a super wind develops that removes the envelope entirely, a phenomenon not yet fully understood (Bernard-Salas 2003). The central, primarily carbon-oxygen core is thus exposed. These cores can have temperatures in the hundreds of thousands of Kelvin, leading to a very strong ionizing source. -

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants

SHELL BURNING STARS: Red Giants and Red Supergiants There is a large variety of stellar models which have a distinct core – envelope structure. While any main sequence star, or any white dwarf, may be well approximated with a single polytropic model, the stars with the core – envelope structure may be approximated with a composite polytrope: one for the core, another for the envelope, with a very large difference in the “K” constants between the two. This is a consequence of a very large difference in the specific entropies between the core and the envelope. The original reason for the difference is due to a jump in chemical composition. For example, the core may have no hydrogen, and mostly helium, while the envelope may be hydrogen rich. As a result, there is a nuclear burning shell at the bottom of the envelope; hydrogen burning shell in our example. The heat generated in the shell is diffusing out with radiation, and keeps the entropy very high throughout the envelope. The core – envelope structure is most pronounced when the core is degenerate, and its specific entropy near zero. It is supported against its own gravity with the non-thermal pressure of degenerate electron gas, while all stellar luminosity, and all entropy for the envelope, are provided by the shell source. A common property of stars with well developed core – envelope structure is not only a very large jump in specific entropy but also a very large difference in pressure between the center, Pc, the shell, Psh, and the photosphere, Pph. Of course, the two characteristics are closely related to each other. -

(GK 1; Pr 1.1, 1.2; Po 1) What Is a Star?

1) Observed properties of stars. (GK 1; Pr 1.1, 1.2; Po 1) What is a star? Why study stars? The sun Age of the sun Nearby stars and distribution in the galaxy Populations of stars Clusters of stars Distances and characterization of stars Luminosity and flux Magnitudes Parallax Standard candles Cepheid variables SN Ia 2) The HR diagram and stellar masses (GK 2; Pr 1.4; Po 1) Colors of stars B-V Blackbody emission HR Diagram Interpretation of HR diagram stellar radii kinds of stars red giants white dwarfs planetary nebulae AGB stars Cepheids Horizontal branch evolutionary sequence turn off mass and ages Masses from binaries Circular orbits solution General solution Spectroscopic binaries Eclipsing spectroscopic binaries Empirical mass luminosity relation 3) Spectroscopy and abundances (GK 1; Pr 2) Stellar spectra OBFGKM Atomic physics H atom others Spectral types Temperature and spectra Boltzmann equation for levels Saha equation for ionization ionization stages Rotation Stellar Abundances More about ionization stages, e.g. Ca and H Meteorite abundances Standard solar set Abundances in other stars and metallicity 4) Hydrostatic balance, Virial theorem, and time scales (GK 3,4; Pr 1.3, 2; Po 2,8) Assumptions - most of the time Fully ionized gas except very near surface where partially ionized Spherical symmetry Broken by e.g., convection, rotation, magnetic fields, explosion, instabilities, etc Makes equations a lot easier Limits on rotation and magnetic fields Homogeneous composition at birth Isolation (drop this later in course) Thermal -

Spring Semester 2010 Exam 3 – Answers a Planetary Nebula Is A

ASTR 1120H – Spring Semester 2010 Exam 3 – Answers PART I (70 points total) – 14 short answer questions (5 points each): 1. What is a planetary nebula? How long can a planetary nebula be observed? A planetary nebula is a luminous shell of gas ejected from an old, low- mass star. It can be observed for approximately 50,000 years; after that it its gases will have ceased to glow and it will simply fade from view. 2. What is a white dwarf star? How does a white dwarf change over time? A white dwarf star is a low-mass star that has exhausted all its nuclear fuel and contracted to a size roughly equal to the size of the Earth. It is supported against further contraction by electron degeneracy pressure. As a white dwarf ages, though, it will radiate, thereby cooling and getting less luminous. 3. Name at least three differences between Type Ia supernovae and Type II supernovae. Type Ia SN are intrinsically brighter than Type II SN. Type II SN show hydrogen emission lines; Type Ia SN don't. Type II SN are thought to arise from core collapse of a single, massive star. Type Ia SN are thought to arise from accretion from a binary companion onto a white dwarf star, pushing the white dwarf beyond the Chandrasekhar limit and causing a nuclear detonation that destroys the white dwarf. 4. Why was SN 1987A so important? SN 1987A was the first naked-eye SN in almost 400 years. It was the first SN for which a precursor star could be identified. -

SHAPING the WIND of DYING STARS Noam Soker

Pleasantness Review* Department of Physics, Technion, Israel The role of jets in the common envelope evolution (CEE) and in the grazing envelope evolution (GEE) Cambridge 2016 Noam Soker •Dictionary translation of my name from Hebrew to English (real!): Noam = Pleasantness Soker = Review A short summary JETS See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A very short summary JFM See review accepted for publication by astro-ph in May 2016: Soker, N., 2016, arXiv: 160502672 A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • Jets: Can be launched outside and Secondary inside the envelope star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets Jets Jets: And on its surface Secondary star RGB, AGB, Red Giant Massive giant primary star Jets A full summary • Jets are unavoidable when the companion enters the common envelope. They are most likely to continue as the secondary star enters the envelop, and operate under a negative feedback mechanism (the Jet Feedback Mechanism - JFM). • When the jets mange to eject the envelope outside the orbit of the secondary star, the system avoids a common envelope evolution (CEE). This is the Grazing Envelope Evolution (GEE). Points to consider (P1) The JFM (jet feedback mechanism) is a negative feedback cycle. But there is a positive ingredient ! In the common envelope evolution (CEE) more mass is removed from zones outside the orbit. -

The MUSE View of the Planetary Nebula NGC 3132? Ana Monreal-Ibero1,2 and Jeremy R

A&A 634, A47 (2020) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201936845 & © ESO 2020 Astrophysics The MUSE view of the planetary nebula NGC 3132? Ana Monreal-Ibero1,2 and Jeremy R. Walsh3,?? 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 Universidad de La Laguna, Dpto. Astrofísica, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain 3 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild Strasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany Received 4 October 2019 / Accepted 6 December 2019 ABSTRACT Aims. Two-dimensional spectroscopic data for the whole extent of the NGC 3132 planetary nebula have been obtained. We deliver a reduced data-cube and high-quality maps on a spaxel-by-spaxel basis for the many emission lines falling within the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) spectral coverage over a range in surface brightness >1000. Physical diagnostics derived from the emission line images, opening up a variety of scientific applications, are discussed. Methods. Data were obtained during MUSE commissioning on the European Southern Observatory (ESO) Very Large Telescope and reduced with the standard ESO pipeline. Emission lines were fitted by Gaussian profiles. The dust extinction, electron densities, and temperatures of the ionised gas and abundances were determined using Python and PyNeb routines. 2 Results. The delivered datacube has a spatial size of 6300 12300, corresponding to 0:26 0:51 pc for the adopted distance, and ∼ × ∼ 1 × a contiguous wavelength coverage of 4750–9300 Å at a spectral sampling of 1.25 Å pix− . The nebula presents a complex reddening structure with high values (c(Hβ) 0:4) at the rim. -

Planetary Nebula Associations with Star Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy Yasmine Kahvaz [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Planetary Nebula Associations with Star Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy Yasmine Kahvaz [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Stars, Interstellar Medium and the Galaxy Commons Recommended Citation Kahvaz, Yasmine, "Planetary Nebula Associations with Star Clusters in the Andromeda Galaxy" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. 1052. http://mds.marshall.edu/etd/1052 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PLANETARY NEBULA ASSOCIATIONS WITH STAR CLUSTERS IN THE ANDROMEDA GALAXY A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Physical and Applied Science in Physics by Yasmine Kahvaz Approved by Dr. Timothy Hamilton, Committee Chairperson Dr. Maria Babiuc Hamilton Dr. Ralph Oberly Marshall University Dec 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Timothy Hamilton at Shawnee State University, for his guidance, advice and support for all the aspects of this project. My committee, including Dr. Timothy Hamilton, Dr. Maria Babiuc Hamilton, and Dr. Ralph Oberly, provided a review of this thesis. This research has made use of the following databases: The Local Group Survey (low- ell.edu/users/massey/lgsurvey.html) and the PHAT Survey (archive.stsci.edu/prepds/phat/). I would also like to thank the entire faculty of the Physics Department of Marshall University for being there for me every step of the way through my undergrad and graduate degree years. -

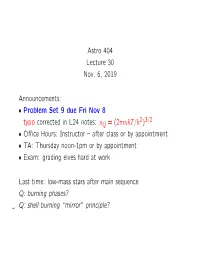

Astro 404 Lecture 30 Nov. 6, 2019 Announcements

Astro 404 Lecture 30 Nov. 6, 2019 Announcements: • Problem Set 9 due Fri Nov 8 2 3/2 typo corrected in L24 notes: nQ = (2πmkT/h ) • Office Hours: Instructor – after class or by appointment • TA: Thursday noon-1pm or by appointment • Exam: grading elves hard at work Last time: low-mass stars after main sequence Q: burning phases? 1 Q: shell burning “mirror” principle? Low-Mass Stars After Main Sequence unburnt H ⋆ helium core contracts H He H burning in shell around core He outer layers expand → red giant “mirror” effect of shell burning: • core contraction, envelope expansion • total gravitational potential energy Ω roughly conserved core becomes more tightly bound, envelope less bound ⋆ helium ignition degenerate core unburnt H H He runaway burning: helium flash inert He → 12 He C+O 2 then core helium burning 3α C and shell H burning “horizontal branch” star unburnt H H He ⋆ for solar mass stars: after CO core forms inert He He C • helium shell burning begins inert C • hydrogen shell burning continues Q: star path on HR diagram during these phases? 3 Low-Mass Post-Main-Sequence: HR Diagram ⋆ H shell burning ↔ red giant ⋆ He flash marks “tip of the red giant branch” ⋆ core He fusion ↔ horizontal branch ⋆ He + H shell burning ↔ asymptotic giant branch asymptotic giant branch H+He shell burn He flash core He burn L main sequence horizontal branch red giant branch H shell burning Sun Luminosity 4 Temperature T iClicker Poll: AGB Star Intershell Region in AGB phase: burning in two shells, no core fusion unburnt H H He inert He He C Vote your conscience–all -

Hydrogen-Deficient Stars

Hydrogen-Deficient Stars ASP Conference Series, Vol. 391, c 2008 K. Werner and T. Rauch, eds. Hydrogen-Deficient Stars: An Introduction C. Simon Jeffery Armagh Observatory, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, N. Ireland, UK Abstract. We describe the discovery, classification and statistics of hydrogen- deficient stars in the Galaxy and beyond. The stars are divided into (i) massive / young star evolution, (ii) low-mass supergiants, (iii) hot subdwarfs, (iv) cen- tral stars of planetary nebulae, and (v) white dwarfs. We introduce some of the challenges presented by these stars for understanding stellar structure and evolution. 1. Beginning Our science begins with a young woman from Dundee in Scotland. The brilliant Williamina Fleming had found herself in the employment of Pickering at the Harvard Observatory where she noted that “the spectrum of υ Sgr is remarkable since the hydrogen lines are very faint and of the same intensity as the additional dark lines” (Fleming 1891). Other stars, well-known at the time, later turned out also to have an unusual hydrogen signature; the spectacular light variations of R CrB had been known for a century (Pigott 1797), while Wolf & Rayet (1867) had discovered their emission-line stars some forty years prior. It was fifteen years after Fleming’s discovery that Ludendorff (1906) observed Hγ to be completely absent from the spectrum of R CrB, while arguments about the hydrogen content of Wolf-Rayet stars continued late into the 20th century. Although these early observations pointed to something unusual in the spec- tra of a variety of stars, there was reluctance to accept (or even suggest) that hydrogen might be deficient. -

The Deaths of Stars

The Deaths of Stars 1 Guiding Questions 1. What kinds of nuclear reactions occur within a star like the Sun as it ages? 2. Where did the carbon atoms in our bodies come from? 3. What is a planetary nebula, and what does it have to do with planets? 4. What is a white dwarf star? 5. Why do high-mass stars go through more evolutionary stages than low-mass stars? 6. What happens within a high-mass star to turn it into a supernova? 7. Why was SN 1987A an unusual supernova? 8. What was learned by detecting neutrinos from SN 1987A? 9. How can a white dwarf star give rise to a type of supernova? 10.What remains after a supernova explosion? 2 Pathways of Stellar Evolution GOOD TO KNOW 3 Low-mass stars go through two distinct red-giant stages • A low-mass star becomes – a red giant when shell hydrogen fusion begins – a horizontal-branch star when core helium fusion begins – an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star when the helium in the core is exhausted and shell helium fusion begins 4 5 6 7 Bringing the products of nuclear fusion to a giant star’s surface • As a low-mass star ages, convection occurs over a larger portion of its volume • This takes heavy elements formed in the star’s interior and distributes them throughout the star 8 9 Low-mass stars die by gently ejecting their outer layers, creating planetary nebulae • Helium shell flashes in an old, low-mass star produce thermal pulses during which more than half the star’s mass may be ejected into space • This exposes the hot carbon-oxygen core of the star • Ultraviolet radiation from the exposed