Figure Skating and the Anthropology of Dance: the Case of Oksana Domnina and Maxim Shabalin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nat Net Threat | Feb. 23, 2008

DAILY MIRROR, Saturday, February 23, 2008 PAGE 15 ‘My Stars AT WAR girl was a NAT NET soulmate’ Nicky says.. THE dad of Stars in their Eyes singer Kesha Wizzart paid an emotional tribute KAREN has been very cross with me to his “soulmate” from the THREAT for years. And I think I deserve that. witness box yesterday. I can only describe the end of our Fred Wizzart, 36, said: skating partnership as a meltdown. “Our relationship was By RICHARD SMITH brilliant. I could not have A BRIDGEND suicide victim left a note in a Soon after we won the British Champi- asked for a better daugh- onships in 1985, I found religion and my entire teenage internet chatroom saying he was going ter... there were so many to kill himself, an inquest heard yesterday. life changed. It made me look at everything good things about her. ‘differently and ask if I was doing the right Nathaniel Pritchard, 15, typed out the message She was like a soulmate.” thing. That included skating. to girlfriend Hannah Brookes after she told him Mr Wizzart was the their eight-month romance was over and she was Looking back, I wish I’d done things first witness in the trial of seeing another boy. differently. Apparently when Cliff Richard Pierre Williams, 33. Det Insp Jason Redrup told the hearing: “He became a Christian he wanted to rush off to He denies murdering replied ‘Just f**k off, go with Dan. I’m going to Africa to help the poor people. But someone Kesha, 18, mum Beverley kill myself and it will be your fault’.” took him aside and said, “Why don’t you Samuels, 36, and brother Hannah rang Nathaniel’s home soon afterwards carry on making music and just send some Fred Junior, 13, with a 2lb to speak to him, the hearing was told. -

2020 TOYOTA US Figure Skating Championships

2020 TOYOTA U.S. FIGURE SKATING CHAMPIONSHIPS OFFICIAL EVENT PROGRAM EVENT CHAMPIONSHIPS OFFICIAL FIGURE SKATING U.S. TOYOTA 2020 Highlander and Camry Hey, Good Looking There they go again. Highlander and Camry. Turning heads wherever they go. The asphalt is their runway, as these two beauties bring sexy back to the cul-de-sac. But then again, some things are always fashionable. Let’s Go Places. Some vehicles prototypes. All models shown with options. ©2019 Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc. 193440-2020 US Championships Program Cover.indd 1 1/1/20 1:33 PM 119901_07417P_FigureSkating_MMLGP_Style_7875x10375_em1_w1a.indd 1 5/10/19 3:01 PM SAATCHI & SAATCHI LOS ANGELES • 3501 SEPULVEDA BLVD. • TORRANCE, CA • 90505 • 310 - 214 - 6000 SIZE: Bleed: 8.625" x 11.125" Trim: 7.875" x 10.375" Live: 7.375" x 9.875" Mechanical is 100% of final BY DATE W/C DATE BY DATE W/C DATE No. of Colors: 4C Type prints: Gutter: LS: Output is 100% of final Project Manager Diversity Review Panel Print Producer Assist. Account Executive CLIENT: TMNA EXECUTIVE CREATIVE DIRECTORS: Studio Manager CREATIVE DIRECTOR: M. D’Avignon Account Executive JOB TITLE: U.S. Figure Skating Resize of MMLGP “Style” Ad Production Director ASSC. CREATIVE DIRECTORS: Account Supervisor PRODUCT CODE: BRA 100000 Art Buyer COPYWRITER: Management Director Proofreading AD UNIT: 4CPB ART DIRECTOR: CLIENT Art Director TRACKING NO: 07417 P PRINT PRODUCER: A. LaDuke Ad Mgr./Administrator ART PRODUCER: •Chief Creative Officer PRODUCTION DATE: May 2019 National Ad Mgr. STUDIO ARTIST: V. Lee •Exec. Creative Director VOG MECHANICAL NUMBER: ______________ PROJECT MANAGER: A. -

KIM GAVIN Creative Director Biog 2019 Copy 3

Kim Gavin Widely acknowledged as one of the UK’s leading talents in the field of stage direc8on, choreography and crea8ve vision. This highly sought a?er Brit and BAFTA Award winning director has been the crea8ve force behind some of the most spectacular visions seen by audiences worldwide. Kim Gavin grew up in Bournemouth and trained at the Royal Ballet School. He followed a successful career as a dancer on television and in the theatre, before turning his ability towards choreography and stage direcon. It was in 1992 whilst working as a choreographer on the BBC’s Royal Variety Performance, that Kim first met Take That. Working on their sell- out arena shows introduced him into the world of live events. Over the last 20 years, Kim has been the crea?ve vision behind some of the most innova?ve and inspira?onal performances in music and live events. He is now widely recognised as one of the UK's leading Crea?ve Directors, working with some the world’s biggest ar?sts on TV spectacu- lars and record-breaking stadium shows. In 1997 Kim Directed and Choreographed the 70’s musical “Oh! What A Night”, starring Kid Creole. It opened with fantas?c reviews to a sell out season at the Blackpool Opera House, followed by Manchester Opera House (1998 & 2000), London Apollo, UK Na?onal Tour 2001 / 2003. Sydney, Melbourne & Hamburg also in 2003. Kim has contributed crea?vely to an impressive list of hugely popular TV shows and live events including; Mobo Awards, Golden Jubilee ‘Party At The Palace’, ‘Concert for Diana’ at Wembley Stadium, ‘The Royal Variety Show’ ‘Children In Need Rocks The Albert Hall’, ‘Help For Heroes Con- cert’ and the ‘Invictus Games’ Opening Ceremony Kim has worked alongside many greats including, Westlife, Pink, Lulu, Robbie Williams, Anastacia, world famous ballerina Darcey Bussell and opera singer Katherine Jenkins, ader conceiving, direc?ng and choreo- graphing the live O2 show, ‘Viva La Diva’. -

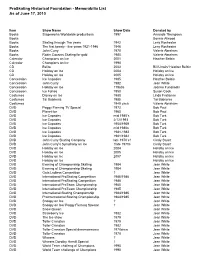

Memorabilia List As of 6-17-10

ProSkating Historical Foundation - Memorabilia List As of June 17, 2010 Item Show Name Show Date Donated by Books Stageworks Worldwide productions 1997 Amanda Thompson Books Bonnie Atwood Books Skating through The years 1942 Leny Rochester Books The first twenty - five years 1921-1946 1946 Leny Rochester Books John Curry 1978 Valerie Abraham Books Robin Cousins Skating for gold 1980 Valerie Abraham Calendar Champions on Ice 2001 Heather Belbin Calendar Champions on Ice 1998 CD Belita 2003 Bill Unwin/ Heather Belbin CD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice CD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice Concession Ice Capades 1985 Heather Belbin Concession John Curry 1982 Jean White Concession Holiday on Ice ?1960s Joanne Funakoshi Concession Ice Follies 1950 Susan Cook Costumes Disney on Ice 1980 Linda Fratianne Costumes Tai Babilonia 1985 Tai Babilonia Costumes 1949 circa Valerie Abraham DVD Peggy Fleming TV Special 1972 Bob Paul DVD Planet Ice 1960 Bob Paul DVD Ice Capades mid 1980’s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 2/12/1993 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1958/1959 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades mid 1980s Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981-1982 Bob Turk DVD Ice Capades 1981/1982 Bob Turk DVD John Curry Skating Company late 1970’s? Cindy Stuart DVD John Curry’s Symphony on Ice ?late 1970s Cindy Stuart DVD Holiday on Ice 2004 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2005 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice 2007 Holiday on Ice DVD Holiday on Ice Holiday on Ice DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Evening of Championship Skating 1984 Jean White DVD Gala Ladiess Competition -

About U.S. Figure Skating Figure Skating by the Numbers

ABOUT U.S. FIGURE SKATING FIGURE SKATING BY THE NUMBERS U.S. Figure Skating is the national governing body for the sport 5 The ranking of figure skating in terms of the size of its fan of figure skating in the United States. U.S. Figure Skating is base. Figure skating’s No. 5 ranking is behind only college a member of the International Skating Union (ISU), the inter- sports, NFL, MLB and NBA in 2009. (Source: US Census and national federation for figure skating, and the U.S. Olympic ESPN Sports Poll) Committee (USOC). 12 Age of the youngest athlete on the 2011–12 U.S. Team — U.S. Figure Skating is composed of member clubs, collegiate men’s skater Nathan Chen (born May 5, 1999) clubs, school-affiliated clubs, individual members, Friends of Consecutive Olympic Winter Games at which at least one U.S. Figure Skating and Basic Skills programs. 17 figure skater has won a medal, dating back to 1948, when Dick Button won his first Olympic gold The charter member clubs numbered seven in 1921 when the association was formed and first became a member of the ISU. 18 International gold medals won by the United States during the To date, U.S. Figure Skating has more than 680 member clubs. 2010–11 season 44 U.S. qualifying and international competitions available on a subscription basis on icenetwork.com U.S. Figure Skating is one of the strongest 52 World titles won by U.S. skaters all-time and largest governing bodies within the winter Olympic movement with more than 180,000 58 International medals won by U.S. -

Project New Scoring System

NEW JUDGING SYSTEM FOR ARTISTIC ROLLER SKATING COMPETITIONS DANCE By Nicola Genchi INDEX INDEX .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1 OWNERSHIP.......................................................................................................................... 3 2 DANCE – GENERAL DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................ 3 3 COUPLE DANCE ..................................................................................................................... 4 3.1 STYLE DANCE .......................................................................................................................... 4 3.2 FREE DANCE ........................................................................................................................... 4 3.3 ONE NO HOLD STEP SEQUENCE (STRAIGHT LINE OR DIAGONAL) ........................................................ 5 Levels…. ................................................................................................................................... 5 Clarifications ............................................................................................................................ 5 3.4 ONE DANCE HOLD STEP SEQUENCE ............................................................................................. 5 Levels…. .................................................................................................................................. -

Viking Voicejan2014.Pub

Volume 2 February 2014 Viking Voice PENN DELCO SCHOOL DISTRICT Welcome 2014 Northley students have been busy this school year. They have been playing sports, performing in con- certs, writing essays, doing homework and projects, and enjoying life. Many new and exciting events are planned for the 2014 year. Many of us will be watching the Winter Olympics, going to plays and con- certs, volunteering in the community, participating in Reading Across America for Dr. Seuss Night, and welcoming spring. The staff of the Viking Voice wishes everyone a Happy New Year. Northley’s Students are watching Guys and Dolls the 2014 Winter Olympics Northley’s 2014 Musical ARTICLES IN By Vivian Long and Alexis Bingeman THE VIKING V O I C E This year’s winter Olympics will take place in Sochi Russia. This is the This year’s school musical is Guy and • Olympic Events first time in Russia’s history that they Dolls Jr. Guys and Dolls is a funny musical • Guys and Dolls will host the Winter Olympic Games. set in New York in the 40’s centering on Sochi is located in Krasnodar, which is gambling guys and their dolls (their girl • Frozen: a review, a the third largest region of Russia, with friends). Sixth grader, Billy Fisher, is playing survey and excerpt a population of about 400,000. This is Nathan Detroit, a gambling guy who is always • New Words of the located in the south western corner of trying to find a place to run his crap game. Year Russia. The events will be held in two Emma Robinson is playing Adelaide, Na- • Scrambled PSSA different locations. -

Welcome WHAT IS IT ABOUT GOLF? EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN

EX-GREENKEEPERS JOIN HEADLAND James Watson and Steve Crosdale, both former side of the business, as well as the practical. greenkeepers with a total of 24 years experience in "This position provides the ideal opportunity to the industry behind them, join Headland Amenity concentrate on this area and help customers as Regional Technical Managers. achieve the best possible results from a technical Welcome James has responsibility for South East England, perspective," he said. including South London, Surrey, Sussex and Kent, James, whose father retired as a Course while Steve Crosdale takes East Anglia and North Manager in December, and who practised the London including Essex, profession himself for 14 years before moving into WHAT IS IT Hertfordshire and sales a year ago, says that he needed a new ABOUT GOLF? Cambridgeshire. challenge but wanted something where he could As I write the BBC are running a series of Andy Russell, use his experience built programmes in conjunction with the 50th Headland's Sales and up on golf courses anniversary of their Sports Personality of the Year Marketing Director said around Europe. Award with a view to identifying who is the Best of that the creation of these "This way I could the Best. two new posts is take a leap of faith but I Most sports are represented. Football by Bobby indicative of the way the didn't have to leap too Moore, Paul Gascoigne, Michael Owen and David company is growing. Beckham. Not, surprisingly, by George Best, who was James Watson far," he explains. "I'm beaten into second place by Princess Anne one year. -

Difficulty Groups of Elements & Features

Communication No. 2182 SYNCHRONIZED SKATING This Communication replaces ISU Communications 2159 Included are: Appendix A - Difficulty Groups of Elements & Features Appendix B - Difficulty Groups of Additional Features Tubbergen, Jan Dijkema, President July 25, 2018 Lausanne, Fredi Schmid, Director General DIFFICULTY GROUPS OF ELEMENTS & FEATURES (Appendix A) ELEMENT ICE COVERAGE REQUIREMENTS Minimum ice coverage; Some Elements (PB, PL, B, C, L, W, NHE, TC and TW etc.) must meet a minimum ice coverage requirement Stopping: Skaters are standing in one (1) place with or without movement of the blade(s) ARTISTIC ELEMENT Definition and Requirements (see Regulations for details) Basic Requirements 1. The Element must first meet the requirements for the respective shape for an Artistic Block, Artistic Circle, Artistic Line, Artistic Wheel; i.e. the minimum number of Skaters in a block, circle, line, or spoke 2. All Skaters must begin in the first shape of the Artistic Element and must return to the Element shape (same or different shape) after the Feature(s) has been executed (if applicable) Artistic Elements: (Artistic Block (AB), Artistic Circle (AC), Artistic Line (AL), Artistic Wheel (AW)) LEVEL BASE LEVEL 1 LEVEL 2 ABB/ACB/ALB/AWB AB1/AC1/AL1/AW1 AB2/AC2/AL2/AW2 An Element that does not Element must meet the basic Element must meet the basic meet the level 1 or level 2 requirements AND must requirements AND must requirements but meets the include one (1) Feature include two (2) different Basic Requirements Features: One (1) Feature from Group A and one (1) Feature from Group B Group A 1. -

Dancing on Ice Comes to St Peter's Top Marks for Clinical Coders

Issue No. 247 1st February 2011 Top marks for Clinical Coders Our Clinical Coding department assurance of the has added to its expertise as quality of our data. four members of the team have recently passed the Clinical This also Coding National Accreditation demonstrates the team’s commitment exam. to continuous This is a highly specialised exam and professional successful candidates have to development, demonstrate a very high practical and making their own theoretical knowledge of their quiet but essential subject. contribution to our annual income. Achieving this accreditation, against Coders Debbie O’Sullivan, Marion Brookes and nationally set standards, shows the Charmaine French with their accreditation certificate, which they share with team member high quality service the team are able Wafaa Haleem. to offer, and gives us further Dancing on Ice comes to St Peter’s Dancing on Ice Both stars thanked staff for celebrities came to St their treatment and their Peter’s two days in a short visits were filmed for row last week. the show. Jennifer’s visit After taking separate was shown last week, but tumbles on the ice during sadly Dominic’s visit was training Jennifer Metcalfe (of not included on the show. Hollyoaks fame) and cricketer Dominic Cork, both Submit your came to A&E with minor story! injuries last Sunday and Monday respectively. Sister If you have a story for Pat Miles was on hand to Aspire please contact treat both contestants, and Giselle Rothwell, Head Dominic was also seen by of Communications, on ext 3470 or via Sister Pat Miles with former England cricketer and radiographer Alan Dancing on Ice contestant Dominic Cork in A&E Francesco. -

Push Comes to Shove As Former Track Stars Eye Bobsleigh Glory

SUNDAY, JANUARY 26, 2014 SPORTS Winter Games a family affair for athletes VIENNA: Sibling rivals, dynasties of champi- Lake Placid and bronze four years later in Sochi, while their sister Allison has skated for won two silvers and one bronze in luge sin- Austria’s Marlies and Bernadette Schild, ons or coaching parents: the Olympic com- Sarajevo. The Kostelic siblings of Croatia- Georgia and now Israel at international level. gles between 1992 and 2002 and is also his German double Olympic champion Maria munity likes to style itself as one big family... Janica and Ivica-have accumulated nine In biathlon, Russia’s Anastazia Kuzmina and manager. Even when they’re not racing, Hoefl-Riesch and her sister Susanne, and and in winter sports, that’s quite often literal- Olympic medals, including four gold, since her brother Anton Shipulin took part in sepa- uncles, dads and other relatives are often Italian siblings Manfred and Manuela ly the case. In disciplines like alpine skiing, 2002. In Turin, she won gold in the women’s rate races in Vancouver in 2010 but still took part of the all-important entourage back- Moelgg. French nordic combined star Jason passed on from one generation to the next combined and he won silver in the men’s home a full set of medals. Olympic genes are stage. Yves Hamelin, head of Canada’s short Lamy-Chappuis, an Olympic and world in remote valleys in Switzerland or Austria, race. Siblings competing together are not an especially strong in some families. Super-G track speed skating program, led his athletes champion, has a cousin, Ronan, in ski jump- there is no shortage of racing dynasties. -

Olympic Champions - Part 1 Shaun White, Dick Button, Peggy Fleming ======

THE KING'S NUMEROLOGY ™ Olympic Champions - Part 1 Shaun White, Dick Button, Peggy Fleming ======================================================= Shaun White Brief: Shaun White is a global snowboarding and skateboarding icon and two-time Olympic Gold Medalist in the Halfpipe: 2006 in Torino (Italy) and 2010 in Vancouver (Canada). The red-haired wonder has dominated his sport for the last decade. As well as being a star, White has made himself a fortune with his prodigious talent and charismatic personality. NBC reported during the Olympics that White doesn't just want to win. He wants to dominate. Check out all the 2s, especially the 29s in his Expression, PE, Soul and Material Soul and the three 9s - domination, charisma, personal magnetism and connection with the public. "Shaun White: Olympic Halfpipe Hero" is posted on King's Numerology Articles page and contains a more in- depth look at Shaun White's chart. Basic Matrix - Shaun White. Natal: Shaun Roger White : 3 September 1986 Roots Lifepath Expression PE Soul M/S Nature M/N Simple 9 2 2 2 2 9 9 Master Potentials 11 11 11 11 General 36 83 119 29 65 54 90 Specific 36 191 227 56 92 135 171 Transition 18 29-20 29-47 11 29 18 36 Void 4: The Numbers 9 and 2 in Shaun White's Chart The Number 9 in White's Numerology Chart The Number 2 in White's Numerology Chart 9: Lifepath 9: Nature 2: Expression [full birth name- Shaun Roger White] 9: Material Nature 2: The Name "White" 9: 1st Name "Shaun" 2: The reality or PE of the name "White" 9: 1st Name "Shaun" PE 2: Life PE - Performance/Experience