Foraging Ecology Drives Mercury Contamination in Chick Gulls From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductive Ecology of Urban-Nesting Glaucous-Winged Gulls Larus Glaucescens in Vancouver, Bc, Canada

Kroc: Reproductive ecology of Glaucous-winged Gulls in Vancouver 155 REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY OF URBAN-NESTING GLAUCOUS-WINGED GULLS LARUS GLAUCESCENS IN VANCOUVER, BC, CANADA EDWARD KROC1,2 1Department of Statistics, University of British Columbia, 2207 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada ([email protected]) 2Department of Educational and Counselling Psychology, and Special Education, University of British Columbia, 2125 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada Received 01 November 2017, accepted 10 July 2018 SUMMARY KROC, E. 2018. Reproductive ecology of urban-nesting Glaucous-Winged Gulls Larus glaucescens in Vancouver, BC, Canada. Marine Ornithology 46: 155–164. The present study investigated the reproductive success and breeding ecology of 102 Glaucous-winged Gull Larus glaucescens pairs nesting in downtown Vancouver, British Columbia during the summer of 2015. These urban breeders enjoyed a remarkably high level of post-hatch fledging success (≥ 85%) compared to previous records for non-urban subpopulations in the region (≈ 70%). A relatively small average initial clutch size of 2.43 eggs was observed, which aligns with a historical analysis of the literature and corroborates the inference that clutch size has declined substantially in the region over the past century. I argue that the high level of post-hatch fledging success is likely attributable to a tendency of urban Glaucous-winged Gulls to establish isolated nesting territories, often on the rooftops of individual buildings, which leads to low intra- and interspecific predation. Given that offspring commonly return to their natal sites to breed later in life, the evolutionary impact of this reproductive differential could be significant for the ecological future of Glaucous-winged Gulls in the region. -

Larus Marinus, L. Argentatus and L. Fuscus from Finland

Migration and wintering strategies of juvenile and adult Larus marinus, L. argentatus and L. fuscus from Finland Mikael Kilpi & Pertti Saurola Kilpi, M . & Saurola, P.: Migration and wintering strategies of juvenile and adult Larus marinus, L. argentatus and L. fuscus from Finland. - Ornis Fennica 61 :1- 8. Finnish ringing data were used to examine the migratory patterns of adult (+5 yr) and juvenile S(1 yr) Great Black-backed, Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gulls from the coast of Finland . The birds generally leave the breeding area in autumn, the Great Black-back making the shortest journey and the Lesser Black-back migrating up to 7500 km. The two larger species winter within the Baltic, while the Lesser Black-back has a large wintering area, which extends down to Equatorial Africa . In contrast to the other two species, the Lesser Black-back largely uses freshwater habitats in winter . There is some evidence that age-dependent differences exist in all species . Juveniles were found to perform a return migration in spring, but considerably (2-3 months) later than the adults . In all three species, some individuals evi- dently stay in the wintering area during summer . The comparatively late return of the Lesser Black-backed adults is suggested to be responsible for the present poor breeding success . Comparison is made with other European populations . It is argued that adults and short-range mig- rants are better able to adjust their migratory behaviour to the prevailing condi- tions than juveniles and long-range migrants. The settlement of adult breeders in marginal areas probably does not require a genetic change in migratory prog- ramming, but the pattern may be shaped by selection acting on the juveniles . -

Identification and Ageing of Glaucous-Winged Gull and Hybrids G

Identification and ageing of Glaucous-winged Gull and hybrids Enno B Ebels, Peter Adriaens & Jon R King laucous-winged Gull Larus glaucescens treated in several (field) guides and identification G breeds around the northern Pacific, from videos published during the last two decades (eg, northern Oregon and Washington, USA, in the Harrison 1983, Grant 1986, Dunn et al 1997, east, via Alaska (including the Aleutian and National Geographic Society 1999, Sibley 2000, Pribilof Islands), USA, to the Komandorskie Doherty & Oddie 2001). This paper discusses the Islands and Kamchatka, north-eastern Russia, in basic aspects of identification of Glaucous-wing- the west. The species winters around the north- ed Gull and various hybrids and illustrates the ern Pacific, from Baja California, Mexico, to different hybrid types and plumages with photo- Hokkaido, Japan (Snow & Perrins 1998). It is a graphs; it does not pretend to be all-inclusive. It rare vagrant in most western states of the USA; it focuses on structure, plumage and bare parts. is very rare inland in central states of the USA, as Differences in voice and/or behaviour (for in- far east as the Great Lakes, and has never been stance, long-call posture) are not treated. The recorded on the American East Coast (cf Sibley paper is based on field studies by Jon King (in 2000). Vagrants have been recorded in Hong Japan and the USA) and Enno Ebels (in Japan), Kong, China, and Hawaii, USA (Snow & Perrins examination by JK of museum skins in various 1998). Amazingly, there are two records of collections, and examination by Peter Adriaens Glaucous-winged Gull in the Western Palearctic: of published and unpublished photographs, a subadult (presumably third-winter) on El including many photographs of spread wings Hierro, Canary Islands, on 7-10 February 1992; from the National Museum of Natural History and an adult at Essaouira, Morocco, on 31 (Washington, DC, USA), the Peabody Museum of January 1995 (Bakker et al 2001 and references Natural History (Yale University, New Haven, therein). -

Distribution of Perfluorinated Compounds in Yellow-Legged Gull Eggs

Science of the Total Environment 416 (2012) 468–475 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Science of the Total Environment journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/scitotenv Distribution of perfluorinated compounds in Yellow-legged gull eggs (Larus michahellis) from the Iberian Peninsula Joana Vicente a, Albert Bertolero b, Johan Meyer a, Paula Viana c, Silvia Lacorte a,⁎ a Department of Environmental Chemistry, Insitute of Environmental Diagnostics and Water Studies, CSIC, Jordi Girona 18-26, 08034 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain b IRTA Aquatic Ecosystems, Ctra. Poble Nou km 5.5, 43540 Sant Carles de la Ràpita, Catalonia, Spain c Divisao de Qualidade da Água, Instituto da Água I.P. Av. Almirante Gago Coutinho, 30. 1049-066 Lisboa, Portugal article info abstract Article history: This study is aimed to evaluate the presence and distribution of Perfluorinated Compounds (PFCs) in Yellow- Received 27 June 2011 legged gull eggs (Larus michahellis) collected from 8 National or Natural Parks from the Iberian Peninsula. In Received in revised form 29 November 2011 each colony, 12 eggs were randomly collected and pooled from 3 areas of the colony and analyzed using liq- Accepted 30 November 2011 uid–solid extraction and liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Perfluorooctanate Available online 29 December 2011 sulfonate (PFOS) was the only compound detected in the eggs and its presence was higher in the colonies sit- uated in NE Iberian Peninsula due to the more industrial and mass urbanization in this area compared to the Keywords: Perfluorinated compounds SW Mediterranean or Atlantic colonies. Accordingly, the Medes site, followed by the Ebro Delta and Colum- Yellow-legged gull bretes, all situated in the NW Mediterranean coast, contained the highest PFOS levels (40.5–54.0 ng/g-ww). -

Notes on Indian Rarities–2: Waterfowl, Diving Waterbirds, and Gulls and Terns Praveen J., Rajah Jayapal & Aasheesh Pittie

Praveen et al. : Indian rarities–2 113 Notes on Indian rarities–2: Waterfowl, diving waterbirds, and gulls and terns Praveen J., Rajah Jayapal & Aasheesh Pittie Praveen J., Jayapal, R., & Pittie, A., 2014. Notes on Indian rarities—2: Waterfowl, diving waterbirds, and gulls and terns. Indian BIRDS 9 (5&6): 113–136. Praveen J., B303, Shriram Spurthi, ITPL Main Road, Brookefields, Bengaluru 560037, Karnataka, India. Email: [email protected]. [Corresponding author.] Rajah Jayapal, Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Anaikatty (Post), Coimbatore 641108, Tamil Nadu, India. Email: [email protected]. Aasheesh Pittie, 2nd Floor, BBR Forum, Road No. 2, Banjara Hills, Hyderabad 500034, Telangana, India. Email: [email protected]. [Continued from Indian BIRDS 8 (5): 125.] n this part, we present annotated notes on 36 species, from the published; this list will include all the species that have been Ifollowing families: reliably recorded, in an apparently wild state, in the country. In • Anatidae (Swans, geese, and ducks) addition, species from naturalised populations, either established • Podicipedidae (Grebes) within the country or outside, from which individual birds • Gaviidae (Loons) sometimes straggle to the region would also be included in the • Phalacrocoracidae (Cormorants) Checklist. For this part of the series, we have excluded some • Laridae (Gulls and terns) anatids that have become rare in recent years having undergone a grave population decline, but were widely reported in India during the nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. This list Table 1. Abbreviations used in the text includes White-headed Duck Oxyura leucocephala, Baikal Teal Abbreviations Reference Anas formosa, Smew Mergellus albellus, Baer’s Pochard Aythya AWC Asian Waterbird Census (www.wetlands.org/awc) baeri, and Pink-headed Duck Rhodonessa caryophyllacea, BMNH Natural History Museum, London (www.nhm.ac.uk) the last now probably locally extinct. -

European Herring Gull in Ontario Ontario Birds 20(1)

3 Articles European Herring Gull in Ontario Michel Gosselin and Ron Pittaway Introduction the middle) compared with two An unidentified first year gull in American Herring Gulls (L. a. juvenal/first basic plumage was col smithsonianus). lected by the National Museum of Natural Sciences (now Canadian Discussion Museum of Nature) in Ottawa, Comparing same age and plumage, Ontario, on 11 November 1974. the European Herring Gull from When Pierre Devillers, of the Ottawa is distinguished from Institut Royal des Sciences American Herring Gulls by the Naturelles (Brussels), visited Ottawa combination of whiter and less ver in 1986, he identified the bird as a miculated bases to its tail feathers Herring Gull of the European sub (creating a more defined subtermi species group Larus argentatus nal tail band), whiter upper tail argentatus/argenteus (Pierre Devillers, coverts and rump, coarser and pers. comm.). He thought it was sparser dark markings on the more similar to nominate argentatus, undertail coverts, paler and more but he could not eliminate argenteus checkered upperparts (including without access to comparative skins. wing coverts and tertials), and a His assessment, however, is consis more streaked breast (Grant 1986, tent with the information in Golley Dubois 1997). It differs from the and Elliott (1993). This specimen is Pontic/Yellow-legged Gull complex the first record of a European (L. cachinnans/michahellis/atlantis), Herring Gull in Ontario and the first and from the Lesser Black-backed specimen for Canada. It is specimen Gull (L. fuscus) , by its heavily number CMN 62001 in the marked greater secondary coverts, Canadian Museum of Nature in more notched tertial edges, and Ottawa. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Species Boundaries in the Herring and Lesser Black-Backed Gull Complex J

Species boundaries in the Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex J. Martin Collinson, David T. Parkin, Alan G. Knox, George Sangster and Lars Svensson Caspian Gull David Quinn ABSTRACT The BOURC Taxonomic Sub-committee (TSC) recently published recommendations for the taxonomy of the Herring Gull and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex (Sangster et al. 2007). Six species were recognised: Herring Gull Larus argentatus, Lesser Black-backed Gull L. fuscus, Caspian Gull L. cachinnans,Yellow-legged Gull L. michahellis, Armenian Gull L. armenicus and American Herring Gull L. smithsonianus.This paper reviews the evidence underlying these decisions and highlights some of the areas of uncertainty. 340 © British Birds 101 • July 2008 • 340–363 Herring Gull taxonomy We dedicate this paper to the memory of Andreas Helbig, our former colleague on the BOURC Taxonomic Sub-committee. He was a fine scientist who, in addition to leading the development of the BOU’s taxonomic Guidelines, made significant contributions to our understanding of the evolutionary history of Palearctic birds, especially chiffchaffs and Sylvia warblers. He directed one of the major research programmes into the evolution of the Herring Gull complex. His tragic death, in 2005, leaves a gap in European ornithology that is hard to fill. Introduction taimyrensis is discussed in detail below, and the Until recently, the Herring Gull Larus argentatus name is used in this paper to describe the birds was treated by BOU as a polytypic species, with breeding from the Ob River east to the at least 12 subspecies: argentatus, argenteus, Khatanga (Vaurie 1965). There has been no heuglini, taimyrensis, vegae, smithsonianus, molecular work comparing the similar and atlantis, michahellis, armenicus, cachinnans, intergrading taxa argentatus and argenteus barabensis and mongolicus (Vaurie 1965; BOU directly and any reference to ‘argentatus’ in this 1971; Grant 1986; fig. -

Identification of American Herring Gull in a Western European Context T

Identification of American Herring Gull in a western European context Pat Lonergan & Killian Mullarney he first American Herring Gull Larus smithso- Committee (BBRC) (Rogers & Rarities Committee T nianus (hereafter smithsonianus) recorded in 2003) and this, coupled with the observation of Europe dates back to November 1937 when a several contentious individuals in, for instance, second-winter bird, ringed as a chick on Kent Britain (Ahmad & Elliott 2000, Vinicombe 2000) Island, New Brunswick, Canada, in August of the and the Netherlands (van Duivendijk & Kok previous year, was caught on a ship 480 km off 1998), Germany and Norway (Martin Gottschling the Spanish coast (Gross 1940). Nothing was and Håken Heggland pers comm) certainly sug- recorded on the appearance of this bird but it is gests that smithsonianus is being actively looked doubtful that the occurrence would have attract- for in other parts of Europe. The few records out- ed any attention had it not been for the fact that side Britain and Ireland include four for France the bird carried a ring. Almost 50 years passed (Dubois et al 1995ab, Frémont et al 2000), two before the next record, a first-winter at Cobh, for Norway (Solbakken et al 2003), four for Cork, south-western Ireland, in November- Portugal (Moore 1994, de Juana & Comité Ibérico December 1986 (O’Sullivan & Smiddy 1990). de Rarezas de la SEO 1995, Hoogendoorn et al The finder of this bird, Jim Wilson, was sufficient- 2003) and one for Spain (de Juana & Comité ly struck by its unusual appearance to record Ibérico de Rarezas de la SEO 1995, Álvarez- detailed field notes. -

A Checklist of Birds of Britain (9Th Edition)

Ibis (2018), 160, 190–240 doi: 10.1111/ibi.12536 The British List: A Checklist of Birds of Britain (9th edition) CHRISTOPHER J. MCINERNY,1,2 ANDREW J. MUSGROVE,1,3 ANDREW STODDART,1 ANDREW H. J. HARROP1 † STEVE P. DUDLEY1,* & THE BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS’ UNION RECORDS COMMITTEE (BOURC) 1British Ornithologists’ Union, PO Box 417, Peterborough PE7 3FX, UK 2School of Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK 3British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, IP24 2PU, UK Recommended citation: British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU). 2018. The British List: a Checklist of Birds of Britain (9th edition). Ibis 160: 190–240. and the Irish Rare Birds Committee are no longer INTRODUCTION published within BOURC reports. This, the 9th edition of the Checklist of the Birds The British List is under continuous revision by of Britain, referred to throughout as the British BOURC. New species and subspecies are either List, has been prepared as a statement of the status added or removed, following assessment; these are of those species and subspecies known to have updated on the BOU website (https://www.bou. occurred in Britain and its coastal waters (Fig. 1). org.uk/british-list/recent-announcements/) at the time It incorporates all the changes to the British List of the change, but only come into effect on the List up to and including the 48th Report of the British on publication in a BOURC report in Ibis. A list of Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee the species and subspecies removed from the British (BOURC) (BOU 2018), and detailed in BOURC List since the 8th edition is shown in Appendix 1. -

Larus Argentatus) in Eastern North America

ANNUAL SPATIAL ECOLOGY OF HERRING GULLS (LARUS ARGENTATUS) IN EASTERN NORTH AMERICA by Christine M. Anderson B. Sc. Trent University 2013 Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Biology) Acadia University Spring Graduation 2017 © by Christine M. Anderson, 2017 ii This thesis by Christine M. Anderson was defended successfully in an oral examination on 25 April 2017. The examining committee for the thesis was: This thesis is accepted in its present form by the Division of Research and Graduate Studies as satisfying the thesis requirements of the degree Master of Science (Biology). …………………………………………….. iii I, Christine M. Anderson, grant permission to the University Librarian at Acadia University to reproduce, loan or distribute copies of my thesis in microform, paper, or electronic formats on a non-profit basis. I, however, retain the copyright in my thesis. iv Table of Contents Table of Contents --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- iv List of Tables --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- v List of Figures ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- vi Abstract --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ix Acknowledgements-------------------------------------------------------------------------------- x Chapter 1 – General introduction and methods ---------------------------------------------- 1 Background -

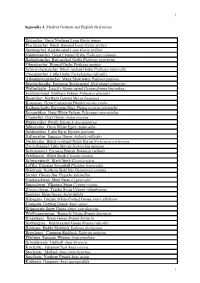

Appendix 4. Modern German and English Bird Names

1 Appendix 4. Modern German and English bird names. Eistaucher Great Northern Loon Gavia immer Prachttaucher Black-throated Loon Gavia arctica Sterntaucher Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Haubentaucher Great Crested Grebe Podiceps cristatus Rothalstaucher Red-necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena Ohrentaucher Horned Grebe Podiceps auritus Schwarzhalstaucher Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis Zwergtaucher Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis Atlantiksturmtaucher Manx Shearwater Puffinus puffinus Sturmschwalbe European Storm-petrel Hydrobates pelagicus Wellenläufer Leach’s Storm-petrel Oceanodroma leucorhoa Eissturmvogel Northern Fulmar Fulmarus glacialis Basstölpel Northern Gannet Morus bassanus Kormoran Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo Krähenscharbe European Shag Phalacrocorax aristotelis Rosapelikan Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus Graureiher Grey Heron Ardea cinerea Purpurreiher Purple Heron Ardea purpurea Silberreiher Great White Egret Ardea alba Seidenreiher Little Egret Egretta garzetta Rallenreiher Squacco Heron Ardeola ralloides Nachtreiher Black-crowned Night Heron Nycticorax nycticorax Zwergdommel Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus Rohrdommel Eurasian Bittern Botaurus stellaris Weißstorch White Stork Ciconia ciconia Schwarzstorch Black Stork Ciconia nigra Löffler Eurasian Spoonbill Platalea leucorodia Waldrapp Northern Bald Ibis Geronticus eremita Sichler Glossy Ibis Plegadis falcinellus Höckerschwan Mute Swan Cygnus olor Singschwan Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus Zwergschwan Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus Saatgans Bean