Vertical Integration in Sports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Game Notes

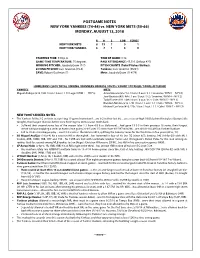

POSTGAME NOTES NEW YORK YANKEES (74-44) vs. NEW YORK METS (50-66) MONDAY, AUGUST 13, 2018 R H E LOB SERIES NEW YORK METS 8 15 1 9 1 NEW YORK YANKEES 5 7 1 5 0 STARTING TIME: 7:09 p.m. TIME OF GAME: 3:18 GAME-TIME TEMPERATURE: 75 degrees PAID ATTENDANCE: 47,233 (Sellout #22) WINNING PITCHER: Jacob deGrom (7-7) PITCH COUNTS (Total Pitches/Strikes): LOSING PITCHER: Luis Severino (15-6) Yankees: Luis Severino (98/64) SAVE: Robert Gsellman (7) Mets: Jacob deGrom (114/79) HOME RUNS (2018 TOTAL / INNING / RUNNERS ON BASE / OUTS / COUNT / PITCHER / SCORE AFTER HR) YANKEES METS Miguel Andújar (#18 / 8th / 2 on / 2 out / 1-0 / Lugo / NYM 7 – NYY 5) Amed Rosario (#5 / 1st / 0 on / 0 out / 3-1 / Severino / NYM 1 – NYY 0) José Bautista (#9 / 4th / 1 on / 0 out / 3-2 / Severino / NYM 4 – NYY 2) Todd Frazier (#11 / 6th / 0 on / 0 out / 0-2 / Cole / NYM 5 – NYY 3) Brandon Nimmo (#15 / 7th / 0 on / 1 out / 1-1 / Cole / NYM 6 – NYY 3) Michael Conforto (#16 / 7th / 0 on / 1 out / 1-1 / Cole / NYM 7 – NYY 3) NEW YORK YANKEES NOTES • The Yankees fell to 3-2 on their season-long 11-game homestand…are 6-2 in their last 8G…are a season-high 10.0G behind first-place Boston (idle tonight), their largest division deficit since finishing the 2016 season 10.0G back. • Suffered their second series loss of the season (also 1-3 from 4/5-8 vs. -

Weller Credits 2019

Production Design and Art Direction United Scenic Artists, Local 829 IATSE 505 Court Street 7P, Brooklyn NY 11231 NYC 212 9797761 Los Angeles 310 3981982 [email protected] IMDB: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0919860/ LINKEDIN: www.linkedin.com/in/wellerdesign www.wellerdesign.com Production Design and Art Direction for film, television and theater. Extensive experience in single and multi camera art direction for features and network/cable television. Skillful, meticulous budgeting combined with quick and accurate drafting. Expertise in assembling and managing crews. Multiple Emmy Awards. Series NEW AMSTERDAM – Network Series - NBC UNIVERSAL 2019 Art Director ARMISTEAD MAUPIN’S TALES OF THE CITY – Mini Series- NETFLIX 2019 Assistant Art Director FIRST WIVE’S CLUB – PARAMOUNT NETWORK 2018 Art Director JESSICA JONES SEASON 3 - MARVEL PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX 2018 Assistant Art Director JULIE’S GREENROOM – JIM HENSON PRODUCTIONS - NETFLIX –2016 Art Director QUANTICO – ABC - 2016 Assistant Art Director Feature Film LOST GIRLS – NETFLIX 2018 Art Director THE COMMUTER – LIONSGATE -2017 Assistant Art Director BRAWL IN CEL BLOCK 99 - RLJE FILMS - 2017 Art Department THE PERFECT GENTLEMAN – SHORT - 2010 Production Design BAD LIEUTENANT –ARIES FILMS -1992 Set Designer THE RAPTURE - FINE LINE FEATURES - 1991 Set Designer THE BLOODHOUNDS OF BROADWAY – COLUMBIA PICTURES - 1989 Assistant Art Director Live Events THE NEW LEVANT - KENNEDY CENTER 2018 GLAMOUR WOMEN OF THE YEAR- CONDE NAST Carnegie Hall 2016, 2017 ALICIA KEYS FOR VEUVE CLIQUOT – Liberty -

At NEW YORK METS (27-33) Standing in AL East

OFFICIAL GAME INFORMATION YANKEE STADIUM • ONE EAST 161ST STREET • BRONX, NY 10451 PHONE: (718) 579-4460 • E-MAIL: [email protected] • SOCIAL MEDIA: @YankeesPR & @LosYankeesPR WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONS: 1923, ’27-28, ’32, ’36-39, ’41, ’43, ’47, ’49-53, ’56, ’58, ’61-62, ’77-78, ’96, ’98-2000, ’09 YANKEES BY THE NUMBERS NOTE 2018 (2017) NEW YORK YANKEES (41-18) at NEW YORK METS (27-33) Standing in AL East: ............1st, +0.5 RHP Domingo Germán (0-4, 5.44) vs. LHP Steven Matz (2-4, 3.42) Current Streak: ...................Won 3 Current Road Trip: ................... 6-1 Saturday, June 9, 2018 • Citi Field • 7:15 p.m. ET Recent Homestand: ................. 4-2 Home Record: ..............22-9 (51-30) Game #61 • Road Game #30 • TV: FOX • Radio: WFAN 660AM/101.9FM (English), WADO 1280AM (Spanish) Road Record: ...............19-9 (40-41) Day Record: ................16-4 (34-27) Night Record: .............24-14 (57-44) AT A GLANCE: Tonight the Yankees play the second game of HOPE WEEK 2018 (June 11-15): This Pre-All-Star ................41-18 (45-41) their three-game Subway Series at the Mets (1-0 so far)…are 6-1 year marks the 10th annual HOPE Week Post-All-Star ..................0-0 (46-30) on their now-nine-game, four-city road trip, which began with a (Helping Others Persevere & Excel), vs. AL East: .................15-9 (44-32) rain-shortened two-game series in Baltimore (postponements an initiative rooted in the belief that vs. AL Central: ..............11-2 (18-15) on 5/31 and 6/3), a split doubleheader in Detroit on Monday acts of good will provide hope and vs. -

Arthouse Film Festival, When Asked How He Made It Look Children Training in the Martial Arts.” Beginning This Month at AMC Loews Mountainside

Page 16 Thursday, September 2, 2010 The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES A WATCHUNG COMMUNICATIONS, INC. PUBLICATION Westfield Resident Tsirigotis ‘Goes to the Mat’ for Martial Arts By MARYLOU MORANO A student of martial arts since he was area. Westfield Boy LaVelle Appears Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times 11, Mr. Tsirigotis holds a black belt in One would expect that with this abun- WESTFIELD – “Back to school” Taekwondo and is the originator of his dance of experience, the author would not only means getting back to the own system of martial arts; it is based take a stance that martial arts are for books; it means heading back to after- on pankration, a combat sport that – every child. Instead, his unbiased look On the YES Network, WFAN Radio school activities as well. blending boxing and wrestling with at martial arts and the martial arts in- strategy – was introduced into the Greek dustry allows each parent to make the By CHRISTIE STORMS meeting the New York Yankees at show, simulcast on TV via the YES Olympic Games in 648 BC and which best decision for his or her child. He Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times their new stadium come true. And (Yankees Entertainment & Sports) featured the philosopher Plato among provides the benefits of martial arts WESTFIELD — In May, the this past week, the same charitable Network and on WFAN 66 AM Ra- its participants. training, but he also provides a list of Make-A-Wish Foundation made 9- organization invited Connor to ap- dio. -

Xtra Package 4

B:36.75" T:36.5" S:36.125" FOR SALES ASSOCIATES ONLY—NOT FOR CUSTOMERS FOR SALES ASSOCIATES ONLY—NOT FOR CUSTOMERS FOR SALES ASSOCIATES ONLY—NOT FOR CUSTOMERS FOR SALES ASSOCIATES ONLY—NOT FOR CUSTOMERS General Market Offers DIRECTV Channel Lineups DIRECTV Channel Lineups En Español Offers ™ 1 REGULAR REGULAR SELECT Over 145 channels, including local channels (in SD and HD) available in over 99% of U.S. households : $ 99 Over 240 top channels, including local channels (in SD and HD) available in over 99% of U.S. $ 99 ® ™ ™ ™ ™ ™ PRICE mo. ULTIMATE 1 2015 SEASON PRICE mo. MÁS LATINO ÓPTIMO MÁS MÁS ULTRA LO MÁXIMO SELECT ENTERTAINMENT CHOICE XTRA ULTIMATE PREMIER™ PACKAGE ABC | CBS | FOX | NBC | PBS | CW & MyTV (available in select markets). households : ABC | CBS | FOX | NBC | PBS | CW & MyTV (available in select markets). INCLUDED 49 86 † Package Package Package Package Package Package Package Package Package Package PACKAGE Includes all channels in XTRA, plus the channels shown in BOLD. Regional Sports fee applies in certain markets. A&E ........................ 265 Celebrity Shopping Network .........95/223 EVINE..........................73/316 INSP .............................364 pivot ............................ 267 Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) ......372 OVER 115 CHANNELS OVER 195 CHANNELS OVER 235 CHANNELS OVER 340 CHANNELS OVER CHANNELS OVER CHANNELS OVER CHANNELS OVER CHANNELS OVER CHANNELS OVER CHANNELS ABC Family.................... 311 Church Channel . .371 EWTN.............................370 Investigation Discovery .......... 285 Pursuit Channel.................... 604 truTV ........................ 246 3 145 150 175 220 240 315 A&E ........................ 265 CNBC........................ 355 Enlace ...........................448 HISTORY ..................... 269 NFL Network .................. 212 TCT Network .......................377 1 1 1 1 AMC......................... 254 CMT......................... 327 Food Network ................ -

Comparing the Brand Strengths of Real Madrid & the New York Yankees

Syracuse University SURFACE Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects Projects Spring 5-1-2012 Marketing Pastimes: Comparing the Brand Strengths of Real Madrid & The New York Yankees Colin Wilson Powers Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone Part of the Sports Management Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Powers, Colin Wilson, "Marketing Pastimes: Comparing the Brand Strengths of Real Madrid & The New York Yankees" (2012). Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects. 157. https://surface.syr.edu/honors_capstone/157 This Honors Capstone Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT In March of 2012, Forbes Magazine ranked the most valuable brands in all of sports. Trailing only Manchester United’s $2.235 billion valuation, the next most valuable franchises are Spain’s Real Madrid of La Liga BBVA, and Major League Baseball’s New York Yankees. As the two of the three most dominant brands in all of sports, Real Madrid and the New York Yankees are frequently mentioned in the same context as one another, but rarely discussed through more extensive market research comparing their brand management strategies. By utilizing Kevin Keller’s acclaimed Customer-Based Brand Equity model, the relative strength of the brands for Real Madrid and the New York Yankees will be assessed based on their ability to successfully integrate six core components within their brand: brand salience, brand performance, brand imagery, brand judgments, brand feelings, and brand resonance. -

Ian Robert Sacks 129 East Grand Street / Mount Vernon, NY, 10552 • (914) 672-3304 • [email protected] See More: Website • Linkedin • Demo Reel

Ian Robert Sacks 129 East Grand Street / Mount Vernon, NY, 10552 • (914) 672-3304 • [email protected] See more: Website • LinkedIn • Demo Reel On-Air Experience: ESPN3/ESPN+, Iona College Athletics August 2012–Present Play-by-Play Announcer/Color Commentator/Sideline Reporter New Rochelle, NY • Announce basketball, softball, volleyball, soccer and lacrosse games for ESPN3/ESPN+ • Assemble post-game video reports, detailing major storylines, highlights, sound bites and statistics Larchmont-Mamaroneck Community Media (LMC Media) May 2014–Present Play-by-Play Announcer/Anchor Mamaroneck, NY • Announce local high school basketball, baseball, football, softball, volleyball and lacrosse games • Anchor weekly news show The Local Live; created, developed and anchored The Local Live Sports segment Spalk October 2020–Present Play-by-Play Announcer Mount Vernon, NY • Announce Liga Primera soccer games and European Volleyball Confederation matches on Sports Flick Binghamton Rumble Ponies June 2019–March 2021 Media Relations & Broadcasting Assistant Binghamton, NY • Served as play-by-play announcer and color commentator for game broadcasts on local radio and MiLB.tv • Handled media relations by compiling and sending out game notes, recaps, press releases and roster moves ESPN Radio Albany August 2015–January 2016 New York Jets Beat Reporter East Rutherford, NJ • Reported on every New York Jets home game by taping and editing video reports and writing blog posts • Provided insight into the state of the Jets on the radio following home games Additional Broadcasting Experience: Madison Square Garden Co. February 2016–Present Production Assistant White Plains, NY • Oversee rotation of graphics on arena’s videoboards at New York Liberty and Westchester Knicks games YES Network April 2021–Present Runner Bronx, NY/Brooklyn, NY • Perform a variety of tasks to assist in the broadcasts of New York Yankees and Brooklyn Nets games Fox 61 October 2018–June 2019 Producer Hartford, CT • Produced the 5 a.m. -

WFAN Live Broadcasts

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – Thursday, September 13, 2018 Contact: Lindsay Salandra, Empire City Casino, [email protected] John Cirillo, Cirillo World 914-260-7436, [email protected] WFAN Radio Steps Out from Behind the Mic at Monday Night Live Broadcasts With Special Co-Host & New York Giants Super Bowl Champ Carl Banks WFAN & NFL Network Correspondent Kim Jones to Host Live Broadcasts from Dan Rooney’s Sports Pub at Empire City Casino This Football Season (Yonkers, NY) – The field isn’t the only place where the action can be seen live this football season as WFAN Radio (660 AM/101.9 FM) gets set to host Monday Night Live broadcasts surrounded by sports fans at the Dan Rooney’s Sports Pub inside of Empire City Casino beginning Monday, September 17. Co-hosted by New York Giants Super Bowl champion, Carl Banks, and WFAN & NFL Network correspondent, Kim Jones, WFAN will air nine shows beginning at 6:30 p.m. prior to Monday Night Football games on September 17, October 1, 8 and 15, November 5, 19 and 26, and December 10 and 17. Another Big Blue champ, David Diehl, will sub for Banks on the October 15 show. Casino guests, restaurant diners, and fans can mingle with the radio hosts prior to and following the program, as well as during commercial breaks, time permitting, for autographs and photos. There will also be $5 food and drink specials every Monday night, as well as during all NFL games. Diners can enjoy Buffalo and BBQ Chicken Wings, Pigs in a Blanket, Mozzarella Sticks, and Bud & Bud Light for just $5 per item. -

The 54Th Annual New York Emmy® Award Nominations

THE 58TH ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED THIS MORNING! MSG Network Gets the Most Nominations with 62 New York, NY – Wednesday, February 11, 2015. The 58th Annual New York Emmy® Award nominations took place this morning at the studios of CUNY-TV. Hosting the announcement was Jacqueline Gonzalez, Executive Director, NY NATAS. Presenting the nominees were Emmy® Award-winner N.J. Burkett, Correspondent, WABC-TV and President of NY NATAS; Emmy® Award-winner Marvin Scott, Senior Correspondent and Anchor/Host, PIX News Close Up, WPIX-TV; Emmy® Award-winner Elizabeth Hashagen, Anchor, News 12 Long Island; and Emmy® Award-winner Tamsen Fadal, Anchor, PIX11 News at 5 and 10,and Host, Backstage on Broadway, WPIX-TV. Total Number of Nominated Entries MSG Network 62 WRNN-TV 4 WPIX-TV 55 News 12 The Bronx 3 YES Network 38 WCNY-TV 3 (MLB Productions for YES Network - 4) WRGB-TV 3 WNBC-TV 37 News 12 Brooklyn 2 News 12 Long Island 30 NY1 Noticias 2 WCBS-TV 25 WENY-TV 2 News 12 Connecticut 24 WKBW-TV 2 SNY 19 WLNY-TV 2 WXTV Univision 41 16 WSTM-TV 2 News 12 Westchester 15 CUNY.edu 2 WNJU Telemundo 47 15 SyracuseStage.org 2 MSG Plus 13 Yankees.com 2 NYC Media 13 BARD Entertainment 1 WABC-TV 13 Cablevision/IFC 1 NJ.com 12 My9 WWOR 1 NJTV 11 NewYork.CBSlocal.com 1 (Rutgers University/ NJTV – 2) NY1.com 1 News 12 New Jersey 10 NYC Media & WNYE-TV 1 Newsday.com 10 SNY.tv 1 WGRZ-TV 10 Time Warner Cable SportsChannel 1 WNYW FOX 5 10 WHAM-TV 1 Thirteen/WNET 9 WHEC-TV 1 PIX11.com 7 WIVB.com 1 NY1 News 7 WMHT.org 1 WLIW 7 WNYE-TV & Lehman College/Lehman Studios 1 WTEN-TV 7 WNYT-TV 1 CUNY-TV 6 7online.com 1 Time Warner Cable News - Rochester 6 EliteDaily.com 1 FiOS1 News 5 WXXI Public Broadcasting 1 WIVB-TV 4 The 58th Annual New York Emmy® Awards will be presented at a Black Tie Gala on Saturday, May 2, 2015 at The Marriott Marquis ~ Times Square. -

SPECTRUM TV PACKAGES Albany | June 2018

SPECTRUM TV PACKAGES Albany | June 2018 TV PACKAGES 111 SYFY 64 LMN 175 Pop 847 FOROtv 112 truTV 68 Disney XD 179 LOGO 849 Ultra Docu SPECTRUM SELECT 113 Comedy Central 74 NFL Network 182 BET HER 850 Canal Sur 116 Paramount Network 86 Disney Junior 208 CNBC World 853 SUR Perú (Includes Spectrum TV Basic 117 VH1 124 UP 253 Boomerang 855 TV Chile and the following services) 118 MTV 128 Reelz 262 Nicktoons 856 Caracol 5 TBS 121 TV Land 130 Nat Geo Wild 263 TeenNick 857 RCN Nuestra Tele 6 WRGB - CBS 122 Freeform 131 Smithsonian Channel 266 Discovery Family 860 CentroamericaTV 8 WXXA - FOX 123 Hallmark Channel 132 Animal Planet 286 MTV Live HD 861 Tele El Salvador 10 WTEN - ABC 126 WGN America 133 Viceland 287 BET Jams 865 Ecuavisa Internacional 11 WMHT - PBS 129 National Geographic 134 fyi, 288 Nick Music 867 TV Venezuela 13 WNYT - NBC 132 Animal Planet 144 Fusion 290 BET Soul 870 Super Canal 23 The Weather Channel 138 Investigation Discovery 145 El Rey Network 303 ESPN Classic 87 1 Telemicro 24 ESPN 160 HGTV 161 DIY Network 307 MLB Strike Zone 872 Television Dominicana 25 ESPN2 162 Food Network 163 Cooking Channel 310 NFL Network 874 WAPA América 26 MSG Plus 165 Travel Channel 169 Fuse 311 NFL RedZone 875 Cubaplay 27 TNT 166 TLC 173 OWN 312 NHL Network 877 Antena 3 Internacional 28 USA Network 167 Bravo 174 Lifetime Real Women 371 ESPN GoalLn/BasesLd 891 FOX Life 29 AMC 168 E! 177 GSN 372 FCS Atlantic 895 Univisión tlnovelas 30 Lifetime 170 Lifetime 180 Discovery Life Channel 373 FCS Central 898 NBC Universo 31 FX 171 Oxygen 184 TV One 374 -

MSG Network Gets the Most Nominations with 68

THE 59TH ANNUAL NEW YORK EMMY® AWARD NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED THIS MORNING! MSG Network Gets the Most Nominations with 68 New York, NY – Tuesday, February 9, 2016. The 59th Annual New York Emmy® Award nominations took place this morning at the studios of CUNY-TV. Hosting the announcement was Denise Rover, President, NY NATAS. Presenting the nominees were Emmy® Award- winner N.J. Burkett, Correspondent, WABC-TV; Emmy® Award-winner Marvin Scott, Senior Correspondent and Anchor/Host, PIX11 News Close Up, WPIX-TV; Emmy® Award-winner Elizabeth Hashagen, Anchor, News 12 Long Island; and Emmy® Award-winner Tamsen Fadal, Anchor, PIX11 News at 5pm, 6pm and 10pm, and Host, Backstage on Broadway, WPIX-TV. Total Number of Nominated Entries MSG Network 68 Brooklyn Free Speech 4 WPIX 49 Time Warner Cable News, Rochester 4 WNBC 44 News 12 The Bronx 3 WXTV Univision 41 34 NJTV 3 News 12 Westchester 31 Time Warner Cable News, Albany 3 News 12 Long Island 27 WJLP 3 News 12 Connecticut 24 WSTM 3 SNY 23 WSYR NewsChannel 9 3 Newsday 20 WTEN 3 YES Network 18 NYDailyNews.com 2 WNJU Telemundo 47 16 PIX11.com 2 WABC 13 Rutgers University/NJTV 2 WCBS 13 SNY.TV 2 NYC Life 12 WLNY 2 WNYW FOX5 12 WNYW FOX5/My9 2 BRIC TV 9 www.Yankees.com 2 Thirteen/WNET 9 ABC7NY.com 1 FiOS1 News 8 FunnyorDieNY.com 1 CUNY-TV 7 Small Factory Productions 1 MSG.com 7 The Public Access Television Corporation 1 MSG+ 7 Vox Media/Eater.com 1 News 12 New Jersey 6 WENY 1 NY1 News 6 WGRZ 1 NY1 Noticias 6 WKBW.com 1 WLIW 6 WNET 1 WXXI Public Broadcasting 6 WRNN 1 NJ.com 5 WROC 1 WIVB 5 www.CUNY.edu 1 WNBC/LXTV 5 WXXA 1 WRGB 5 The 59th Annual New York Emmy® Awards will be presented at a Black Tie Gala on Saturday, March 19, 2016 at The Marriott® Marquis ~ Times Square. -

2012 Ivy League FOOTBALL

BROWN • COLUMBIA • CORNELL • DARTMOUTH • HARVARD • PENN • PRINCETON • YALE 2012 Ivy League FOOTBALL Week 3 • September 24, 2012 Contact: Scottie Rodgers • [email protected] • 609-258-2999 2012 STANDINGS THIS WEEK The 2012 Ivy League football schedule rolls on Ivy League Overall with a Week 3 schedule highlighted by Penn at GP Record Win % PF PA GP Record Win % PF PA Streak Dartmouth in a key Ancient Eight clash on the Harvard 1 1-0-0 1.000 45 31 2 2-0-0 1.000 73 44 W 11 NBC Sports Network. Both teams come into Cornell 1 1-0-0 1.000 45 6 2 1-1-0 0.500 72 40 W 1 the matchup on different ends of streaks as the Brown 1 0-1-0 0.000 31 45 2 1-1-0 0.500 55 66 L 1 2-0 Big Green has won its last five in a row, Yale 1 0-1-0 0.000 6 45 2 1-1-0 0.500 30 66 L 1 while the 0-2 Quakers have come up short in Dartmouth 0 0-0-0 0.000 0 0 2 2-0-0 1.000 48 17 W 5 their last four games dating back to last Columbia 0 0-0-0 0.000 0 0 2 1-1-0 0.500 23 29 L 1 season. Princeton and Columbia meet in the Princeton 0 0-0-0 0.000 0 0 2 0-2-0 0.000 34 38 L 9 Big Apple as the two look to rebound from Penn 0 0-0-0 0.000 0 0 2 0-2-0 0.000 29 52 L 4 tough Week 2 losses.