Evidence of Climate Change Coping and Adaptation Practices by Smallholder Farmers in Northern Ghana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper East Region

REGIONAL ANALYTICAL REPORT UPPER EAST REGION Ghana Statistical Service June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ghana Statistical Service Prepared by: ZMK Batse Festus Manu John K. Anarfi Edited by: Samuel K. Gaisie Chief Editor: Tom K.B. Kumekpor ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There cannot be any meaningful developmental activity without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, and socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. The Kilimanjaro Programme of Action on Population adopted by African countries in 1984 stressed the need for population to be considered as a key factor in the formulation of development strategies and plans. A population census is the most important source of data on the population in a country. It provides information on the size, composition, growth and distribution of the population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of resources, government services and the allocation of government funds among various regions and districts for education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users with an analytical report on the 2010 PHC at the regional level to facilitate planning and decision-making. This follows the publication of the National Analytical Report in May, 2013 which contained information on the 2010 PHC at the national level with regional comparisons. Conclusions and recommendations from these reports are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based policy formulation, planning, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programs. -

Prospecting for Groundwater in the Bawku West District of the Upper East Region of Ghana Using the Electromagnetic and Vertical Electrical Sounding Methods C

PROSPECTING FOR GROUNDWATER IN THE BAWKU WEST DISTRICT OF THE UPPER EAST REGION OF GHANA USING THE ELECTROMAGNETIC AND VERTICAL ELECTRICAL SOUNDING METHODS C. Adu Kyere, R. M. Noye, and Aboagye Menyeh Department of Physics, Geophysics Section, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, University Post Office, Kumasi, Ghana ABSTRACT An integrated approach involving the Electromagnetic (EM) and Vertical electrical sounding (VES) survey methods, has been used to locate potential drilling sites to find groundwater for twenty (20) rural communities in the Bawku West District of the Upper East Region of Ghana. The EM method involved the use of the Geonics EM 34-3 equipment to obtain traversing data for the horizontal dipole (HD) and vertical dipole (VD) modes at station intervals of 10 m for a 20 m coil separation. The EM survey provided subsurface information relating to positions of high electrical conductivity anomalies which presumably pointed to locations for groundwater structures. As a follow up, the VES was carried out with respect to the anomalous positions, using the dipole-dipole configuration with the McOhm-EL resistivity meter. The VES enabled the estimation of the depth of the weathered layer to the bed rock. The results of the VES data were interpreted quantitatively by modeling using IX1D V.3 software. The study identified prospective sites for drilling of bore- holes to provide potable water for the communities. Results for the VES suggested that the aquifer zones in the area under study are mainly deeply weathered and fractured. The lithology for some of the recommended drilled points correlated well with the results obtained from the EM and VES investigations. -

Bawku West District

BAWKU WEST DISTRICT Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the Bawku West district is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Netsforlife® Anglican Diocesan Development and Relief Organization (ADDRO)

Episcopal Relief & Development (ERD)/ NetsforLife® Anglican Diocesan Development and Relief Organization (ADDRO) Malaria Communities Program: Ghana FINAL REPORT Program Location: Bawku West and Garu-Tempane districts, Upper East Region (UER), Ghana Cooperative Agreement Number: GHS-A-00-09-00006-00 Program Dates: October 1, 2009 – September 20, 2012 Date of Submission: November 14, 2012 Report Prepared by: Abagail Nelson, Senior Vice President for Programs, Episcopal Relief & Development Gifty Tetteh, Strategic Outreach Officer, NetsforLife® , Episcopal Relief & Development Dr. Stephen Dzisi, Technical Director, NetsforLife®, Episcopal Relief & Development Denise DeRoeck, Consultant Writer Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 A: Final Year Report: Main Accomplishments........................................................... 2 B. Methodology for the project’s final evaluation..................................................... 16 C. Main accomplishments of the MCP project ........................................................ 16 D. Questions related to MCP objectives.................................................................. 34 1. New USAID partners or networks identified by the project ........................ 34 2. Evidence of an increase in local capacity to undertake community-based malaria prevention and treatment activities during the project period........ 34 3. Evidence or indication that local ownership -

Using Traditional Agroecological Knowledge to Adapt to Climate Change and Variability in the Upper East Region of Ghana

This is a repository copy of Using traditional agroecological knowledge to adapt to climate change and variability in the Upper East Region of Ghana. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/176259/ Version: Published Version Article: Baffour-Ata, F., Antwi-Agyei, P., Apawu, G.O. et al. (4 more authors) (2021) Using traditional agroecological knowledge to adapt to climate change and variability in the Upper East Region of Ghana. Environmental Challenges, 4. 100205. ISSN 2667-0100 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envc.2021.100205 Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) licence. This licence only allows you to download this work and share it with others as long as you credit the authors, but you can’t change the article in any way or use it commercially. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Environmental Challenges 4 (2021) 100205 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Environmental Challenges journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/envc Using traditional agroecological knowledge to adapt to climate change and variability in the Upper East Region of Ghana Frank Baffour-Ata a,∗, Philip Antwi-Agyei -

Upper East Region

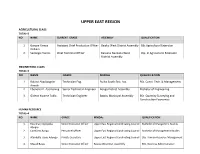

UPPER EAST REGION AGRICULTURAL CLASS TOTAL=2 NO NAME CURRENT GRADE ASSEMBLY QUALIFICATION 1. Gangre Yamya Assistant Chief Production Officer Bawku West District Assembly BSc Agricultural Extension William 2. Sadongo Francis Chief Technical Officer Kassena Nankana West Dip. In Agricultural Extension District Assembly ENGINEERING CLASS TOTAL=3 NO NAME GRADE MMDAs QUALIFICATION 1. Roland Akadipagrim Technician Eng. Builsa South Dist. Ass. BSc. Const. Tech. & Management Amoak 2. Ebenezer P. Asomaning Senior Technician Engineer Bongo District Assembly Bachelor of Engineering 3. Gideon Kwame Toklo Technician Engineer Bawku Municipal Assembly BSc. Quantity Surveying and Construction Economics HUMAN RESOURCE TOTAL=4 NO NAME GRADE MMDAs QUALIFICATION 1. Rosemary Ayinpoka Senior Executive Officer Upper East Regional Cordinating Council Bachelor of Mangement Studies Abugre 2. Comfort Changu Personnel Officer Upper East Regional Cordinating Council Bachelor of Management Studies 3. Atambilla Jacob Adongo Private Secretary Upper East Regional Cordinating Council BSc. Human Resource Management 4. Masud Bawa Senior Executive Officer Bawku West Dist. Assembly BSc. Business Administration PROCUREMENT CLASS TOTAL=2 NO NAME MMDAs DEGREE CURRENT GRADE 1. Ashorm Lawson Korbla Kassena Nankana west BSc. Procurement and Supply Senior Procurement Assistant District Assembly Chain Management 2. Marizuk Ibrahim Bolgatanga Mun. Assembly BSc. Procurement and Supply Senior Procurement Assistant Chain Management ADMINISTRATION CLASS TOTAL=1 NO NAME ASSEMBLY DEGREE DATE ACQUIRED 1. Rosemary Ayinpoka Abugre Upper East RCC ( Feeder Roads) Bachelor of Management Studies Senior Executive Officer INTERNAL AUDIT CLASS TOTAL=1 NO NAME ASSEMBLY DEGREE CURRENT GRADE 1. Lucas Kansang Bawku Municipal Assembly Bachelor of Commerce Mass Education Officer ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH CLASS TOTAL=4 NO NAME GRADE MMDAs PROGRAM OF STUDY Assistant Chief Environmental BSc. -

The Role of Micro-Credit in Economic Empowerment of Disabled Persons in the Upper East Region, Ghana

UNIVERSITY FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES THE ROLE OF MICRO-CREDIT IN ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT OF DISABLED PERSONS IN THE UPPER EAST REGION, GHANA BY , _ JOHN A WUMBILA (B.A IDS) UDS/MDS/0054/07 THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF AFRICAN AND GENERAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, UNIVERSITY FOR DEVELOPMENT STUDIES, TAMALE, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY DEGREE IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES NOVEMBER, 2011 ~ . ABSTRACT Micro-credit has been acknowledged as a resourceful means of enhancing people economic activities and eliminating poverty among the poor. In Ghana, many organisations including those for disabled persons have adopted micro-credit as a strategy for enhancing empowerment. This study sought to explore, highlight and provide scientific information on the role of micro-credit in the economic empowerment of disabled persons using the Anglican and Community-Based Rehabilitation micro-credit programmes in the Bongo and Builsa Districts. A mixed-method approach was employed examining 140 disabled beneficiaries and 40 disabled non beneficiaries of the CBR micro-credit. The study used the borrowers (disabled micro-credit beneficiaries) recall of the “before-after” situation and also gauged the effects through disabled non-micro-credit beneficiaries’ perception on the effects of micro-credit on beneficiaries. This study found that micro-credit increased 84% of disabled entrepreneurs’ profit margins and income levels by 85% per annum. The study further ascertained that through micro credit 68.4% of disabled persons now have ‘bigger’ say in the use and management of their resources and 21.4% have gained better recognition and change in decision making position. -

BAWKU WEST DISTRICT ASSEMBLY (B) EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE

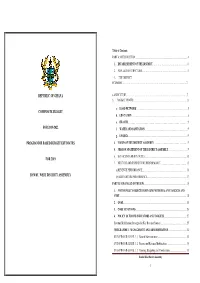

Table of Contents PART A: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 4 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE DISTRICT……………………………………………...4 2. POPULATION STRUCTURE……………………………………………………….........5 3. THE DISTRICT ECONOMY……………………………………………………………………………………...7 REPUBLIC OF GHANA a.AGRICUTURE…………………………………………………………………………………7 b. MARKET CENTRE………..………………………………………………………………8 c. ROAD NETWORK ........................................................................................................ 8 COMPOSITE BUDGET d. EDUCATION ................................................................................................................. 8 e. HEALTH ......................................................................................................................... 9 FOR 2019-2022 f. WATER AND SANITATION ....................................................................................... 9 g. ENERGY ......................................................................................................................... 9 PROGRAMME BASED BUDGET ESTIMATES 4. VISION OF THE DISTRICT ASSEMBLY .................................................................... 9 5. MISSION STATEMENT OF THE DISTRICT ASSEMBLY ....................................... 9 6. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2018 ..................................................................................... 10 FOR 2019 7. REVENUE AND EXPENDITURE PERFORMANCE .................................................... 15 (a)REVENUE PERFORMANCE......................................................................................... -

Regreening Africa Ghana News 2019 Edition Brief from Project Manager

Regreening Africa Ghana News 2019 edition Brief from Project Manager Over the years, acute and prolonged dry farmer groups on regreening approaches and seasons, overgrazing, rampant bush fires and introducing the same to new .members and indiscreet felling of trees have translated to communities in targeted districts. increased decline in forest cover, loss of indigenous biodiversity and decreased soil 2. Interactions with policy makers through fertility. multi-stakeholder and advocacy campaigns The second approach encourages champion Thankfully, simple restoration practices promoted farmers and community leaders to communicate by the Regreening Africa project are improving the benefits enjoyed since adopting regreening livelihoods, food security and resilience to approaches to policy makers. This is to facilitate climate change for smallholder farmers in Garu advancement of environmental policies to favour Tempane, Bawku and Mion Districts. land restoration, especially with beneficiaries in mind. An example is a multi-level stakeholder The two implementing partners, World Vision workshop held in Tamale from 26 to 28 Ghana and Catholic Relief Services (CRS) made November 2018, courtesy of ICRAF's SHARED giant strides in the second year of (Stakeholder Engagement to Risk-Informed implementation. With technical support from Decision Making) team. World Agroforestry (ICRAF), the ambitious target of restoring 90,000 hectares may be within Currently, 16,863 hectares are under various reach. The team attributes progress to the forms of restoration through agroforestry and following approaches: Farmer-Managed Natural Regeneration approaches, with 7,495 households adopting. 1. Direct intervention with communities in However, the team needs to create awareness of three districts these approaches to have as many stakeholders This approach comprises of training farmers and and communities on board. -

Report of Community Analyses for Sustainable Intensification of Cereal‐Based Farming System in the Sudano‐Sahelian Zone in Ghana

Report of community analyses for sustainable intensification of cereal‐based farming system in the Sudano‐Sahelian zone in Ghana I. Y. Dugje, I. A. Teli, A. Larbi, I. Gyamfi, S. S. J. Buah, R.A.L. Kanton, J. M. Kombiok, A. Y. Kamara and I. Hoeschle‐Zeledon Produced by University of Maiduguri Borno State Agricultural Development Programme International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) CSIR‐Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (CSIR‐SARI) Published by International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) 25 May 2012 www.africarising.net The Africa Research In Sustainable Intensification for the Next Generation (Africa RISING) program comprises three research‐for‐development projects supported by the United States Agency for International Development as part of the U.S. government’s Feed the Future initiaative. Through action research and development partnerships, Africa RISING will create opportunities for smallholder farm housseholds to move out of hunger and pooverty through sustainably intensified farming systems that improve food, nutrition, and income security, particularly for women and children, and conserve or enhance the natural resource base. The three projects are led by the International Institute of Tropical Agriculturre (in West Africa and East and Southern Africa) and the International Livestock Research Institute (in the Ethiopian Highlands). The International Food Policy Research Institute leaads an associated project on monitoring, evaluation and impact assessment. This document is licensed for use under a Creative Commons Attribution‐Noncommercial‐SShare Alike 3.0 Unported License 1 LEAD RESOURCE PERSONS Coordinating Team Dr. Irmgard Zeledon, IITA Ibadan Dr. Asamoah Larbi, Africa Rising, Ghana Dr. Isaac Gyamfi, Africa Rising, Ghana Dr. Alpha Y. -

Indigenous Leafy Vegetables in the Upper East Region of Ghana: Opportunities and Constraints for Conservation and Commercialisation

International Centre for development CBUD Centre for Biodiversity oriented Research in Agriculture Utilisation and Development INDIGENOUS LEAFY VEGETABLES IN THE UPPER EAST REGION OF GHANA: OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS FOR CONSERVATION AND COMMERCIALISATION Working Document Series 102 Ghana – 2002 INDIGENOUS LEAFY VEGETABLES IN THE UPPER EAST REGION OF GHANA: OPPORTUNITIES AND CONSTRAINTS FOR CONSERVATION AND COMMERCIALISATION Stephen Amisah Jitendra Prasad Jaiswal Armen Khalatyan Suzana Kiango Nikoloz Mikava In collaboration with Victoria Adarkwa Aduasah and Joyce Bediako This report is the product of team work with equal contribution from the authors whose names are listed in alphabetical order International Centre for development Centre for Biodiversity Utilisation and oriented Research in Agriculture (ICRA) Development (CBUD) P.O. Box 88, 6700 AB Wageningen P.O. Box UP 1106 The Netherlands IRNR KNUST-KUMASI, Ghana ABSTRACT This study examined the conservation, utilisation and potential for commercialisation of some indigenous leafy vegetables (ILVs) in the Upper East Region of Ghana. The study was implemented through a joint field study programme by the International Centre for development oriented Research in Agriculture (ICRA) in the Netherlands and the Centre for Biodiversity Utilisation and Development (CBUD) in Kumasi, Ghana. The study was carried out in four districts in the Upper East Region namely Bolgatanga, Bongo, Bawku West and Kassena-Nankana. The study employed the ARD approach, which is demand driven and integrates the diverse perspectives of all stakeholders and beneficiaries. Participatory methods were employed to collect relevant qualitative and quantitative information. Indigenous leafy vegetables are cultivated under both rainfed and irrigated conditions in the study area. Bito (Hibiscus sabdariffa), Berese (Hibiscus cannabinus), Bento (Vigna unguiculata), Alefu (Amaranthus cruentus), Okro (Abelmuscus esculentus), Spider plant (Cleome gynandra), Luffa sp., and Sambola are the popular cultivated ILVs. -

GARU DISTRICT ASSEMBLY SUB-PROGRAMME: SP 1.2: Finance and Revenue Mobilization

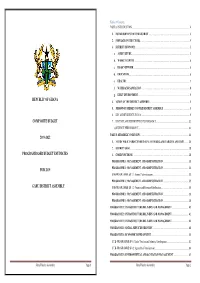

Table of Contents PART A: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 4 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE DISTRICT ........................................................................................ 4 2. POPULATION STRUCTURE ........................................................................................................... 4 3. DISTRICT ECONOMY ..................................................................................................................... 5 a. AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................................. 5 b. MARKET CENTRE ....................................................................................................................... 6 c. ROAD NETWORK ......................................................................................................................... 6 d. EDUCATION ................................................................................................................................... 6 e. HEALTH .......................................................................................................................................... 7 f. WATER AND SANITATION ........................................................................................................ 8 g. BUILT ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................................... 9 REPUBLIC