Succession and Gold Mining at Manso-Nkwanta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ghana), 1922-1974

LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN EWEDOME, BRITISH TRUST TERRITORY OF TOGOLAND (GHANA), 1922-1974 BY WILSON KWAME YAYOH THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON IN PARTIAL FUFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY APRIL 2010 ProQuest Number: 11010523 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010523 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 DECLARATION I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for Students of the School of Oriental and African Studies concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or part by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. SIGNATURE OF CANDIDATE S O A S lTb r a r y ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the development of local government in the Ewedome region of present-day Ghana and explores the transition from the Native Authority system to a ‘modem’ system of local government within the context of colonization and decolonization. -

South Dayi District

SOUTH DAYI DISTRICT i Copyright © 2014 Ghana Statistical Service ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT No meaningful developmental activity can be undertaken without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, in addition to its socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. A population census is the most important source of data on the size, composition, growth and distribution of a country’s population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of national resources and government services, including the allocation of government funds among various regions, districts and other sub-national populations to education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users, especially the Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies, with district-level analytical reports based on the 2010 PHC data to facilitate their planning and decision-making. The District Analytical Report for the South Dayi District is one of the 216 district census reports aimed at making data available to planners and decision makers at the district level. In addition to presenting the district profile, the report discusses the social and economic dimensions of demographic variables and their implications for policy formulation, planning and interventions. The conclusions and recommendations drawn from the district report are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence- based decision-making, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programmes. -

Ghana Poverty Mapping Report

ii Copyright © 2015 Ghana Statistical Service iii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The Ghana Statistical Service wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the Government of Ghana, the UK Department for International Development (UK-DFID) and the World Bank through the provision of both technical and financial support towards the successful implementation of the Poverty Mapping Project using the Small Area Estimation Method. The Service also acknowledges the invaluable contributions of Dhiraj Sharma, Vasco Molini and Nobuo Yoshida (all consultants from the World Bank), Baah Wadieh, Anthony Amuzu, Sylvester Gyamfi, Abena Osei-Akoto, Jacqueline Anum, Samilia Mintah, Yaw Misefa, Appiah Kusi-Boateng, Anthony Krakah, Rosalind Quartey, Francis Bright Mensah, Omar Seidu, Ernest Enyan, Augusta Okantey and Hanna Frempong Konadu, all of the Statistical Service who worked tirelessly with the consultants to produce this report under the overall guidance and supervision of Dr. Philomena Nyarko, the Government Statistician. Dr. Philomena Nyarko Government Statistician iv TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ............................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ -

Volta Region

REGIONAL ANALYTICAL REPORT VOLTA REGION Ghana Statistical Service June, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Ghana Statistical Service Prepared by: Martin K. Yeboah Augusta Okantey Emmanuel Nii Okang Tawiah Edited by: N.N.N. Nsowah-Nuamah Chief Editor: Nii Bentsi-Enchill ii PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT There cannot be any meaningful developmental activity without taking into account the characteristics of the population for whom the activity is targeted. The size of the population and its spatial distribution, growth and change over time, and socio-economic characteristics are all important in development planning. The Kilimanjaro Programme of Action on Population adopted by African countries in 1984 stressed the need for population to be considered as a key factor in the formulation of development strategies and plans. A population census is the most important source of data on the population in a country. It provides information on the size, composition, growth and distribution of the population at the national and sub-national levels. Data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census (PHC) will serve as reference for equitable distribution of resources, government services and the allocation of government funds among various regions and districts for education, health and other social services. The Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) is delighted to provide data users with an analytical report on the 2010 PHC at the regional level to facilitate planning and decision-making. This follows the publication of the National Analytical Report in May, 2013 which contained information on the 2010 PHC at the national level with regional comparisons. Conclusions and recommendations from these reports are expected to serve as a basis for improving the quality of life of Ghanaians through evidence-based policy formulation, planning, monitoring and evaluation of developmental goals and intervention programs. -

National Instrument 43-101 Technical Report

ASANKO GOLD MINE – PHASE 1 DEFINITIVE PROJECT PLAN National Instrument 43-101 Technical Report Prepared by DRA Projects (Pty) Limited on behalf of ASANKO GOLD INC. Original Effective Date: December 17, 2014 Amended and Restated Effective January 26, 2015 Qualified Person: G. Bezuidenhout National Diploma (Extractive Metallurgy), FSIAMM Qualified Person: D. Heher B.Sc Eng (Mechanical), PrEng Qualified Person: T. Obiri-Yeboah, B.Sc Eng (Mining) PrEng Qualified Person: J. Stanbury, B Sc Eng (Industrial), Pr Eng Qualified Person: C. Muller B.Sc (Geology), B.Sc Hons (Geology), Pr. Sci. Nat. Qualified Person: D.Morgan M.Sc Eng (Civil), CPEng Asanko Gold Inc Asanko Gold Mine Phase 1 Definitive Project Plan Reference: C8478-TRPT-28 Rev 5 Our Ref: C8478 Page 2 of 581 Date and Signature Page This report titled “Asanko Gold Mine Phase 1 Definitive Project Plan, Ashanti Region, Ghana, National Instrument 43-101 Technical Report” with an effective date of 26 January 2015 was prepared on behalf of Asanko Gold Inc. by Glenn Bezuidenhout, Douglas Heher, Thomas Obiri-Yeboah, Charles Muller, John Stanbury, David Morgan and signed: Date at Gauteng, South Africa on this 26 day of January 2015 (signed) “Glenn Bezuidenhout” G. Bezuidenhout, National Diploma (Extractive Metallurgy), FSIAMM Date at Gauteng, South Africa on this 26 day of January 2015 (signed) “Douglas Heher” D. Heher, B.Sc Eng (Mechanical), PrEng Date at Gauteng, South Africa on this 26 day of January 2015 (signed) “Thomas Obiri-Yeboah” T. Obiri-Yeboah, B.Sc Eng (Mining) PrEng Date at Gauteng, South Africa on this 26 day of January 2015 (signed) “Charles Muller” C. -

The Composite Budget of the Nkwanta South District Assembly for the 2016

REPUBLIC OF GHANA THE COMPOSITE BUDGET OF THE NKWANTA SOUTH DISTRICT ASSEMBLY FOR THE 2016 FISCAL YEAR Nkwanta South District Assembly Page i For Copies of this MMDA’s Composite Budget, please contact the address below: The Coordinating Director, Nkwanta South District Assembly Volta Region This 2016 Composite Budget is also available on the internet at: www.mofep.gov.gh or www.ghanadistricts.com Nkwanta South District Assembly Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................................................................ iv SECTION I: ASSEMBLY‟S COMPOSITE BUDGET STATEMENT .................................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... -

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Fecal Sludge Treatment Interventions in Ghana

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF FECAL SLUDGE TREATMENT INTERVENTIONS IN GHANA ESI AWUAH Department of Civil Engineering, KNUST, Kumasi Ghana AHMED ISSAHAKU Department of Civil Engineering, KNUST, Kumasi Ghana MARTHA OSEI MARFO Department of Water and Sanitation UCC, Cape Coast Ghana SAMPSON ODURO-KWARTENG Department of Civil Engineering, KNUST, Kumasi Ghana MICHEAL ADDO AZIATSI Department of Civil Engineering, KNUST, Kumasi Ghana NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PLANNING COMMISSION COPENHAGEN CONSENSUS CENTER © 2020 Copenhagen Consensus Center [email protected] www.copenhagenconsensus.com This work has been produced as a part of the Ghana Priorities project. Some rights reserved This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution Please cite the work as follows: #AUTHOR NAME#, #PAPER TITLE#, Ghana Priorities, Copenhagen Consensus Center, 2020. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0. Third-party-content Copenhagen Consensus Center does not necessarily own each component of the content contained within the work. If you wish to re-use a component of the work, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that re-use and to obtain permission from the copyright owner. Examples of components can include, but are not limited to, tables, figures, or images. PRELIMINARY DRAFT AS OF -

CODEO's Statement on the Official Results of The

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CODEO’S STATEMENT ON THE OFFICIAL RESULTS OF THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS CONTACT Mr. Albert Arhin CODEO National Coordinator Phone: +233 (0) 24 474 6791 / (0) 20 822 1068 Secretariat: +233 (0) 244 350 266/ 0277 744 777 Email: [email protected] Website: www.codeoghana.org Thursday, December 10, 2020 Accra, Ghana Introduction On Sunday, December 6, 2020, the Coalition of Domestic Election Observers (CODEO), in its press statement, communicated to the nation its intention to once again employ the Parallel Vote Tabulation (PVT) methodology to observe the 2020 presidential election, just as it did in 2008, 2012 and 2016. The PVT methodology is a reliable tool available to independent and non-partisan citizens’ election observer groups around the world for verifying the accuracy of official presidential elections results. In keeping with our protocols, which is that CODEO releases its PVT findings after the official results have been announced by the Electoral Commission, CODEO is here to release its PVT estimates for the presidential election. CODEO’s PVT estimates for the presidential results form part of its comprehensive election observation activities for the 2020 elections that covered voter registration exercise, pre-election environment observation for three months (September to November), and election day observation. The PVT Methodology The PVT is an advanced and scientific election observation technique that combines well-established statistical principles and Information Communication Technology (ICT) to observe elections. The PVT involves deploying trained accredited Observers to a nationally representative random sample of polling stations. On Election-Day, PVT Observers observe the entire polling process and transmit reports about the conduct of the polls and the official vote count in real-time to a central election observation database, using the Short Message Service (SMS) platform. -

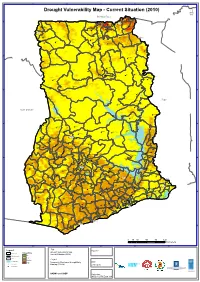

Drought Vulnerability

3°0'0"W 2°0'0"W 1°0'0"W 0°0'0" 1°0'0"E Drought Vulnerability Map - Current Situation (2010) ´ Burkina Faso Pusiga Bawku N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Gwollu Paga ° 1 1 1 1 Zebilla Bongo Navrongo Tumu Nangodi Nandom Garu Lambusie Bolgatanga Sandema ^_ Tongo Lawra Jirapa Gambaga Bunkpurugu Fumbisi Issa Nadawli Walewale Funsi Yagaba Chereponi ^_Wa N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 0 0 1 1 Karaga Gushiegu Wenchiau Saboba Savelugu Kumbungu Daboya Yendi Tolon Sagnerigu Tamale Sang ^_ Tatale Zabzugu Sawla Damongo Bole N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 9 9 Bimbila Buipe Wulensi Togo Salaga Kpasa Kpandai Côte d'Ivoire Nkwanta Yeji Banda Ahenkro Chindiri Dambai Kintampo N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° ° 8 Sampa 8 Jema Nsawkaw Kete-krachi Kajeji Atebubu Wenchi Kwame Danso Busunya Drobo Techiman Nkoranza Kadjebi Berekum Akumadan Jasikan Odumase Ejura Sunyani Wamfie ^_ Dormaa Ahenkro Duayaw Nkwanta Hohoe Bechem Nkonya Ahenkro Mampong Ashanti Drobonso Donkorkrom Nkrankwanta N N " Tepa Nsuta " 0 Va Golokwati 0 ' Kpandu ' 0 0 ° Kenyase No. 1 ° 7 7 Hwediem Ofinso Tease Agona AkrofosoKumawu Anfoega Effiduase Adaborkrom Mankranso Kodie Goaso Mamponteng Agogo Ejisu Kukuom Kumasi Essam- Debiso Nkawie ^_ Abetifi Kpeve Foase Kokoben Konongo-odumase Nyinahin Ho Juaso Mpraeso ^_ Kuntenase Nkawkaw Kpetoe Manso Nkwanta Bibiani Bekwai Adaklu Waya Asiwa Begoro Asesewa Ave Dapka Jacobu New Abirem Juabeso Kwabeng Fomena Atimpoku Bodi Dzodze Sefwi Wiawso Obuasi Ofoase Diaso Kibi Dadieso Akatsi Kade Koforidua Somanya Denu Bator Dugame New Edubiase ^_ Adidome Akontombra Akwatia Suhum N N " " 0 Sogakope 0 -

Presentation (PDF)1.24 MB

Improved Access to Medicines through Local Production Martha Gyansa-Lutterodt Director of Pharmaceutical Services Ministry of Health, Ghana 3/21/2013 Introduction • Access to medicines remain a global challenge; and affect LMICs to varying extents, Ghana inclusive • Local manufacture of medicines contribute significantly to the improvement of access to medicines through simple supply chains • The interphase between private sector and public sector to improve access remain a potential yet to be explored fully • Thus the interlock between access to medicines and the rate of local production; and quality and capacity building are areas to be explored for Ghana 3/21/2013 Introduction (2) • The health challenge in Ghana major factor in poverty • Many deaths preventable with timely access to appropriate & affordable medicines • Ghana depends largely on imports from Asia, frequently with long lead times • Still have challenges with quality of some imports 3/21/2013 Ghana Map #BAWKU #BONGO #ZEBILLA #TUMU #NAVRONGO # #SANDEMA B#YOLGATANGA #LAWRA LAWRA # Upper East #GAMBAGA NADAWLI # #WALEWALE Upper West #Y# WA #GUSHIEGU #SABOBA Northern #SAVELUGU TOLON TAMALE YENDI # #Y# # #ZABZUGU #DAMONGO #BOLE #BIMBILA #SALAGA #NKWANTA #KINTAMPO Brong Ahafo #KETE-KRACHI #WENCHI #ATEBUBU #KWAME DANSO TECHIMAN #DROBO # #NKORANZA #KADJEBI # BEREKUM # #EJURA JASIKAN #SUNYANI #DORMAA AHENKRO #Y #HOHOE #BECHEM Ashanti DONKORKROM # #TEPA # #KENYASE NO. 1 OFINSO KPANDU # #AGONA AKROFOSO MANK#RANSO #EFFIDUASE #GOASO #MAMPONTENG KUM#ASI#EJISU # #Y KONONGO-ODUMASE #MAMPONG -

Mapping Forest Landscape Restoration Opportunities in Ghana

MAPPING FOREST LANDSCAPE RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES IN GHANA 1 Assessment of Forest Landscape Restoration Assessing and Capitalizing on the Potential to Potential In Ghana To Contribute To REDD+ Enhance Forest Carbon Sinks through Forest Strategies For Climate Change Mitigation, Landscape Restoration while Benefitting Poverty Alleviation And Sustainable Forest Biodiversity Management FLR Opportunities/Potential in Ghana 2 PROCESS National Assessment of Off-Reserve Areas Framework Method Regional Workshops National National National - Moist Stakeholders’ Assessment of validation - Transition Workshop Forest Reserves Workshop - Savannah - Volta NREG, FIP, FCPF, etc 3 INCEPTION WORKSHOP . Participants informed about the project . Institutional commitments to collaborate with the project secured . The concept of forest landscape restoration communicated and understood . Forest condition scoring proposed for reserves within and outside the high forest zone 4 National Assessment of Forest Reserves 5 RESERVES AND NATIONAL PARKS IN GHANA Burkina Faso &V BAWKU ZEBILLA BONGO NAVRONGO TUMU &V &V &V &V SANDEMA &V BOLGATANGA &V LAWRA &V JIRAPA GAMBAGA &V &V N NADAWLI WALEWALE &V &V WA &V GUSHIEGU &V SABOBA &V SAVELUGU &V TOLON YENDI TAMALE &V &V &V ZABZUGU &V DAMONGO BOLE &V &V BIMBILA &V Republic of SALAGA Togo &V NKWANTA Republic &V of Cote D'ivoire KINTAMPO &V KETE-KRACHI ATEBUBU WENCHI KWAME DANSO &V &V &V &V DROBO TECHIMAN NKORANZA &V &V &V KADJEBI &V BEREKUM JASIKAN &V EJURA &V SUNYANI &V DORMAA AHENKRO &V &V HOHOE BECHEM &V &V DONKORKROM TEPA -

Northern Sector

LIST OF VOCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS REGISTERED WITH NVTI NORTHERN SECTOR NO SCHOOLS REGISTRATION LOCATION TRADE TELEPHONE NUMBER NUMBER 1. Community Development Voc Tech Inst NVTI/168/NR Tamale Catering/Dressmaking/Home Management 2. Grich Computer & Secretarial NVTI/268/NR Tamale Typing/Secretarial Duties/Computer Literacy 0245602342 3. Standard Promotion Institute NVTI/259/NR Tamale Office Procedures/Typewriting/English Language/ 071 22042 Mathematics/Shorthand/Social Studies/Economics 0244835632 Communications 4. Community Development Vocational Inst. NVTI/389/NR Tamale Dressmaking/Cookery/Hairdressing 071 22623 5. Savelugu Vocational School NVTI/459/NR Savelegu Hairdressing/Dressmaking/Cookery/General 0541449715 Electrical/Secretarial Studies/ICT/Painting 6. Integrated Vocational Training School NVTI/456/NR Nyankpale C&J/Dressmaking/Cookery/ICT/Painting/Hairdressing 0244785269 Secretarial Studies/Masonry 7. Advanced School of Accountancy/Mgt NVTI/422/NR Northern Secretarial Studies/ICT 0249399665 Studies 0208381002 8. Community Base Centre Secretarial Inst NVTI/423/NR Northern Secretarial Studies/ICT 0244157397 9. Presbyterian Vocational Training Centre NVTI/454/NR Nakpanduri Cookery/C&J 0248205076 10. Sawla Girls Vocational Institute NVTI/455/NR Northern Dressmaking/Cookery/Hand weaving/Textile Dec 0207701736 Secretarial Duties/ICT/Hairdressing UPPER WEST REGION NO SCHOOLS REGISTRATION LOCATION TRADE TELEPHONE NUMBER NUMBER 1. St Clare’s Vocational Institute NVTI/056/UWR Tumu Dressmaking/Catering/Textile Hand Weaving 0390 91001 2. St Anne’s Vocational Institute NVTI/057/UWR Nandom Dressmaking/Catering/Textile Hand Weaving 020-9387559 3. St Basilide’s Vocational Institute NVTI/059/UWR Kaleo Welding/General Electrical/Masonry/C&J 0248256932 UPPER EAST REGION NO SCHOOLS REGISTRATION LOCATION TRADE TELEPHONE NUMBER NUMBER 1. Women’s Training Institute NVTI/144/UER Bolgatanga Dressmaking/Catering 0243289664 2.